Fumihiko Maki creates a minimalist, angular home for the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto

Every monumental museum is inspired by a great collection. In the case of the sparkling white-stone Aga Khan Museum, opening next week in the outskirts of Toronto, it's the 1,000 Muslim texts, architectural elements, fountains, crystal, paintings and shahnameh, or epic poems, amassed by the holy leader of the Ismailis and his ancestors.

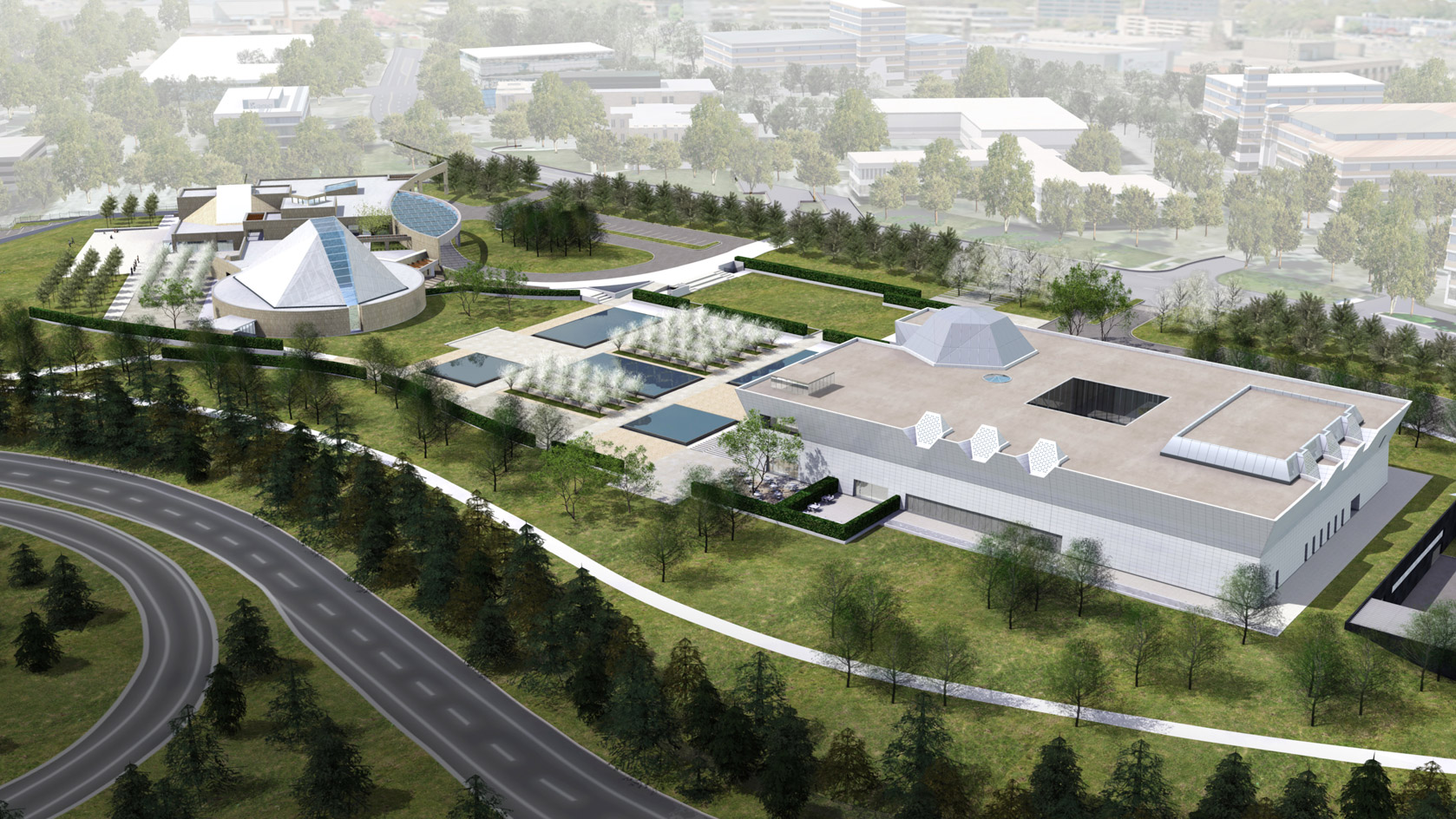

When, in 2007, he began a public tour of his private collection, the Aga Khan sought out Fumihiko Maki to fashion its permanent home. A Pritzker Prize-winner from Japan and architect of the Aga Khan Foundation's Canadian headquarters in Ottawa, Maki drew up 10,000 sq m of towering gallery spaces housed within a minimalist angular form - shaped not unlike an open packing box - assembled on a precise grid of 1m Brazilian granite slabs. (He might have used marble had the climate not been so unforgivingly Canadian.)

The angled facades were designed to play with the arc of the sun, throwing light and shadow onto the surrounding terraces and reflecting pools. 'The play of light is the focus,' says Andrew Bernaus of Moriyama & Teshima, architects of record on the project, 'not the design.'

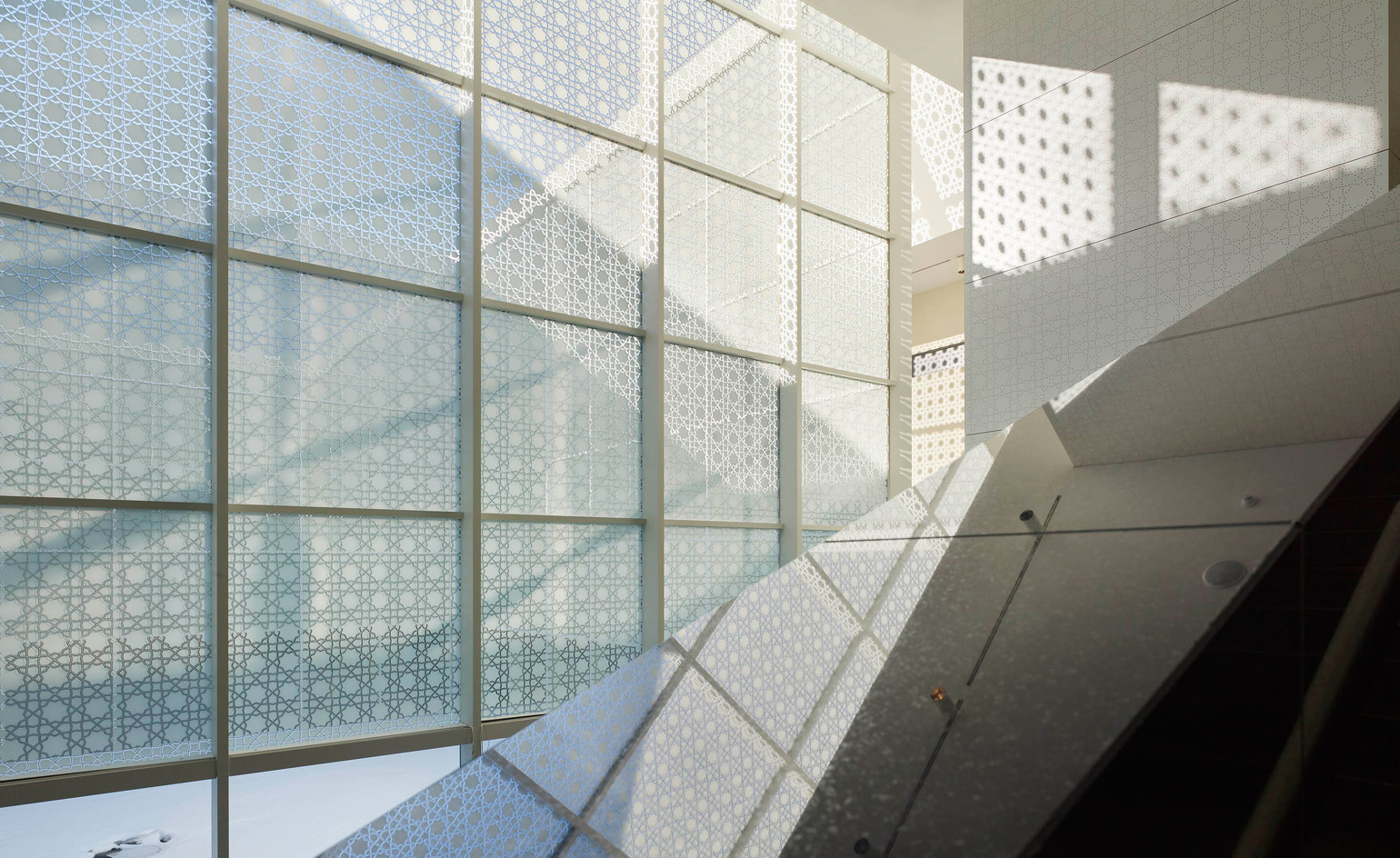

The light effects continue inside, where a small stone courtyard (with a star-shaped drain at the centre and underfloor heating to melt the winter snow) is enclosed in glass etched with a mashrabiya pattern, an ancient Islamic motif reinterpreted by Maki. Light filtered through the patterns splashes on the white walls at different elevations throughout the day. In the upper galleries, built to house the temporary exhibitions, hexagonal skylights, or 'lanterns', introduce shafts of ambient light - the hexagon being symbolic, in the faith, of heaven. Curator Henry Kim, plucked from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford to run the Aga Khan, says, 'When it's partly cloudy, the natural light raises up the light levels, then the clouds drop it down - so you can see the space breathing.'

Elsewhere the surfaces are flawlessly smooth, from the black granite that conceals the escalators to the slender 10m-high steel columns that anchor the white granite walls. Those walls are soundproofed for acoustics, to foil the high ceilings. Even the exit doors and electrical panels are hidden within the surfaces, invisible to anyone who doesn't know of their existence. Bernaus references Adolf Loos' Ornament and Crime when he says, 'You don't use ornamentation to cover things up just because you can't figure it out.'

In the auditorium, the building's crown jewel, the temperature is controlled from grilles hidden beneath each individual seat. That allows the origami dome, inspired by a bazaar in Iran, to rise unfettered over walls panelled with strips of teak. An angular access staircase spirals around in a hexagonal formation, divine against lapis-blue plaster wall, Maki's only concession to colour.

It's a palette that will please Toronto's Ismaili community, accustomed to the simple, cool aesthetics and vast, naturally lit spaces. Yet Kim, who is collaborating with the Hermitage and Louvre museums on some exhibitions, is adamant his museum offers a secular experience. 'The Muslim population is the "low-hanging fruit", to be sure,' he says, 'but our collection is a primer, for everyone, and part of a trend in Islamic art, which is rising to the surface as a significant artform.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The angled facades were designed to play with the arc of the sun, throwing light and shadow onto the surrounding terraces and reflecting pools

The light effects continue inside, where a small stone courtyard is enclosed in glass etched with a mashrabiya pattern, an ancient Islamic motif reinterpreted by Maki

The colour palette will please Toronto's Ismaili community, accustomed to the simple, cool aesthetics and vast, naturally lit spaces

The surfaces are flawlessly smooth, from the black granite that conceals the escalators to the slender 10m-high steel columns that anchor the white granite walls

Light filtered through the patterns splashes on the white walls at different elevations throughout the day

An angular access staircase spirals around in a hexagonal formation, divine against lapis-blue plaster wall, Maki's only concession to colour

The hexagonal skylights, or 'lanterns', introduce shafts of ambient light - the hexagon being symbolic, in the faith, of heaven

The exit doors and electrical panels are hidden within the surfaces, invisible to anyone who doesn't know of their existence

The Aga Khan Museum will hold a collection of 1,000 Muslim texts, architectural elements, fountains, crystal, paintings and shahnameh, or epic poems, amassed by the holy leader of the Ismailis and his ancestors

Based in London, Ellen Himelfarb travels widely for her reports on architecture and design. Her words appear in The Times, The Telegraph, The World of Interiors, and The Globe and Mail in her native Canada. She has worked with Wallpaper* since 2006.

-

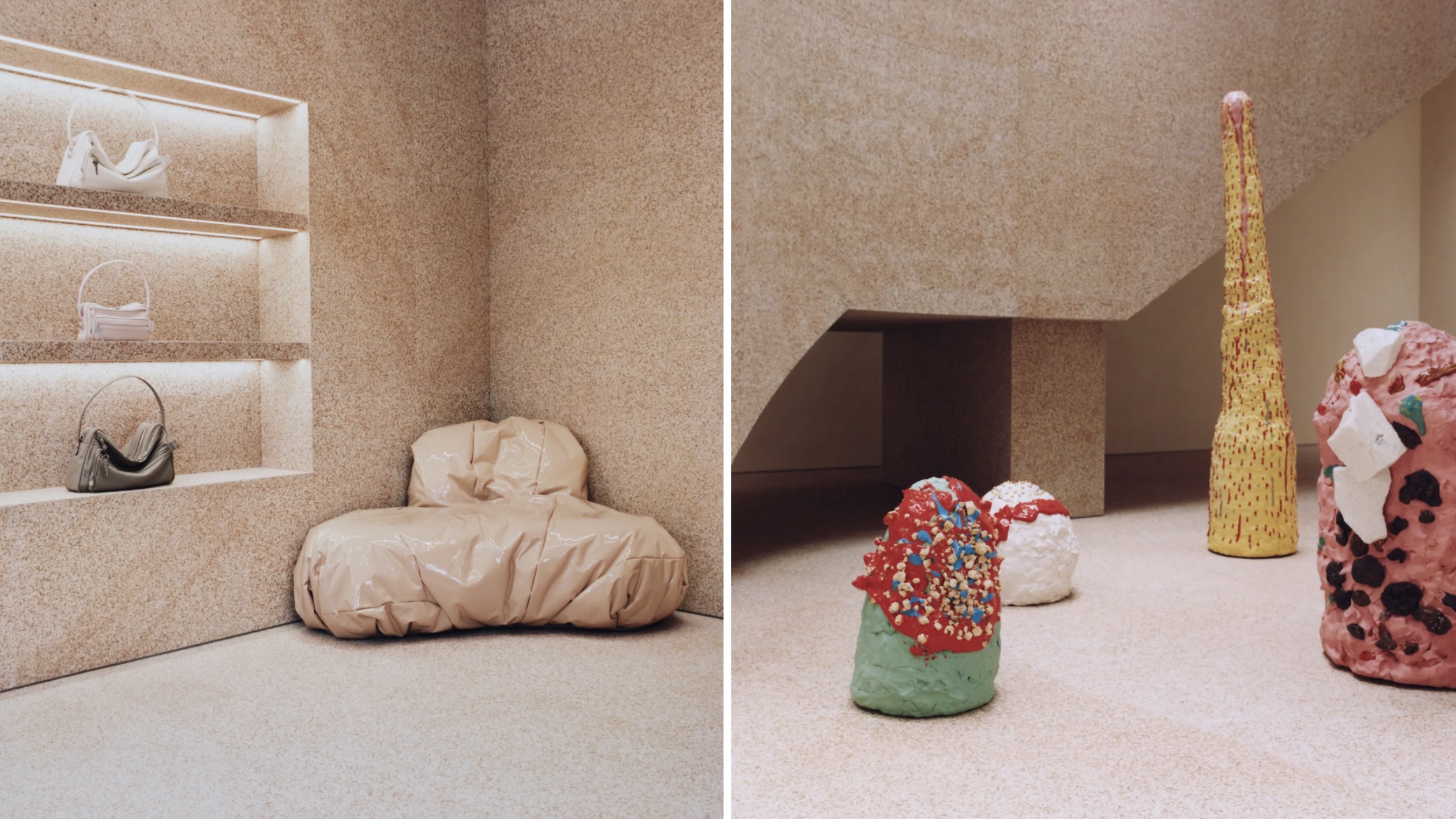

In 2025, fashion retail had a renaissance. Here’s our favourite store designs of the year

In 2025, fashion retail had a renaissance. Here’s our favourite store designs of the year2025 was the year that fashion stores ceased to be just about fashion. Through a series of meticulously designed – and innovative – boutiques, brands invited customers to immerse themselves in their aesthetic worlds. Here are some of the best

-

The Wallpaper* team’s travel highlights of the year

The Wallpaper* team’s travel highlights of the yearA year of travel distilled. Discover the destinations that inspired our editors on and off assignment

-

The architecture of Mexico's RA! draws on cinematic qualities and emotion

The architecture of Mexico's RA! draws on cinematic qualities and emotionRA! was founded by Cristóbal Ramírez de Aguilar, Pedro Ramírez de Aguilar and Santiago Sierra, as a multifaceted architecture practice in Mexico City, mixing a cross-disciplinary approach and a constant exchange of ideas

-

Welcome to The Gingerbread City – a baked metropolis exploring the idea of urban ‘play’

Welcome to The Gingerbread City – a baked metropolis exploring the idea of urban ‘play’The Museum of Architecture’s annual exhibition challenges professionals to construct an imaginary, interactive city entirely out of gingerbread

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom Malibu beach pads to cosy cabins blanketed in snow, Wallpaper* has featured some incredible homes this month. We profile our favourites below

-

The Grand Egyptian Museum – a monumental tribute to one of humanity’s most captivating civilisations – is now complete

The Grand Egyptian Museum – a monumental tribute to one of humanity’s most captivating civilisations – is now completeDesigned by Heneghan Peng Architects, the museum stands as an architectural link between past and present on the timeless sands of Giza

-

Explore the riches of Morse House, the Canadian modernist gem on the market

Explore the riches of Morse House, the Canadian modernist gem on the marketMorse House, designed by Thompson, Berwick & Pratt Architects in 1982 on Vancouver's Bowen Island, is on the market – might you be the new custodian of its modernist legacy?

-

Cosy up in a snowy Canadian cabin inspired by utilitarian farmhouses

Cosy up in a snowy Canadian cabin inspired by utilitarian farmhousesTimbertop is a minimalist shelter overlooking the woodland home of wild deer, porcupines and turkeys

-

Buy yourself a Sanctuary, a serene house above the British Columbia landscape

Buy yourself a Sanctuary, a serene house above the British Columbia landscapeThe Sanctuary was designed by BattersbyHowat for clients who wanted a contemporary home that was also a retreat into nature. Now it’s on the market via West Coast Modern

-

La Maison de la Baie de l’Ours melds modernism into the shores of a Québécois lake

La Maison de la Baie de l’Ours melds modernism into the shores of a Québécois lakeACDF Architecture’s grand family retreat in Quebec offers a series of flowing living spaces and private bedrooms beneath a monumental wooden roof

-

Peel back maple branches to reveal this cosy midcentury Vancouver gem

Peel back maple branches to reveal this cosy midcentury Vancouver gemOsler House, a midcentury Vancouver home, has been refreshed by Scott & Scott Architects, who wanted to pay tribute to the building's 20th-century modernist roots