Remembering Claude Parent's unique take on modernist architecture

We look back on Claude Parent's slant on modernist architecture, five years after the iconic architect's passing, by revisiting Wallpaper* contributing editor Emma O'Kelly's meeting with him in 2007

Alexandre Guirkinger - Photography

Claude Parent is one of France's most revered modern architects, and in 2005 he was invited to become a member of the Academie des Beaux-Arts. For the inauguration ceremony, he had to dress up in an overblown white bow-tie, embroidered tails with more than an echo of Widow Twanky about them and carry a ninja-style sword that he himself designed. ‘You should have seen me,' he chuckles, ‘the costume was ridiculous, and I had to buy it!' The 204-year-old institution is France's most prestigious arts body and is full of composers, painters, sculptors and a sprinkling of architects, éminences grises all, but Parent stands out from his fellow professionals – Paul Andreu and Roger Taillibert among them – in that he dropped out of Paris's École des Beaux-Arts and so never qualified. Which may explain his unorthodox approach to buildings.

He started out in 1942, a time, he says, ‘that is not remembered for its enthusiasm for architecture', and during his long career, has hung out with all the ‘avant-gardists' of the day. He collaborated with Yves Klein on a series of paintings of a 'petite stripteaser' and the design of some fountains for the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, held a conference on a cliff in Folkestone, England, in 1966 with Peter Cook of anarcho British architects Archigram (‘To our surprise, everyone came!'), and completed a six-month stint at Le Corbusier's studio, something he found less than exciting. ‘He was very much the boss and it was a bit suffocating. But when he was there, you saw his genius, although he never made any money; his buildings took too long and were so expensive,' says Parent.

Opening spread with Villa Drusch from Wallpaper's 2007 article on Claude Parent

For most of his career, Parent ran his own bureau in the Paris suburb of Neuilly, where he was born and still lives today. In the mid-1960s he devised a theory, along with critic Paul Virilio, called the fonction oblique, for which he is most famous. This declared that buildings should be all about ramps, slopes and angles, wall-free where possible; that space should predominate over surface. More radical ideas called for the creation of the 'oblique city', which looked like a giant concrete wave, and in 1968 the duo almost got away with suspending themselves in mid-air in two isolated tilted cells as an ‘experiment in living'. Alongside some of the more outré ideas, though, Parent put his theory into practice and created some incredible, experimental and iconic buildings. For the French Pavilion at the 1970 Venice Biennale, he constructed floors that had a 28 per cent incline, and his Villa Drusch in Versailles is a rectangular concrete box of a house, propped up improbably on one of its corners.

Built in 1963 for local industrialist Gaston Drusch, it's all tricky angles and open spaces, and the outdoor lap pool, which Drusch used to jump into from his bedroom window, looks as contemporary as anything today. Says Parent: ‘This house was a lesson in space; it gives you views you couldn't have imagined on a maquette and the proportions are really good. But it was an ambitious project and everyone said that it was going to fall over.' How it ever got planning permission is anyone's guess, sitting as it does amid grand 19th-century villas and cosy suburban houses, but Parent says that by the time he designed it, he was well known enough to get it through. ‘Every house I've ever built [and there are around a dozen across France] has been refused planning permission,' he says, laughing.

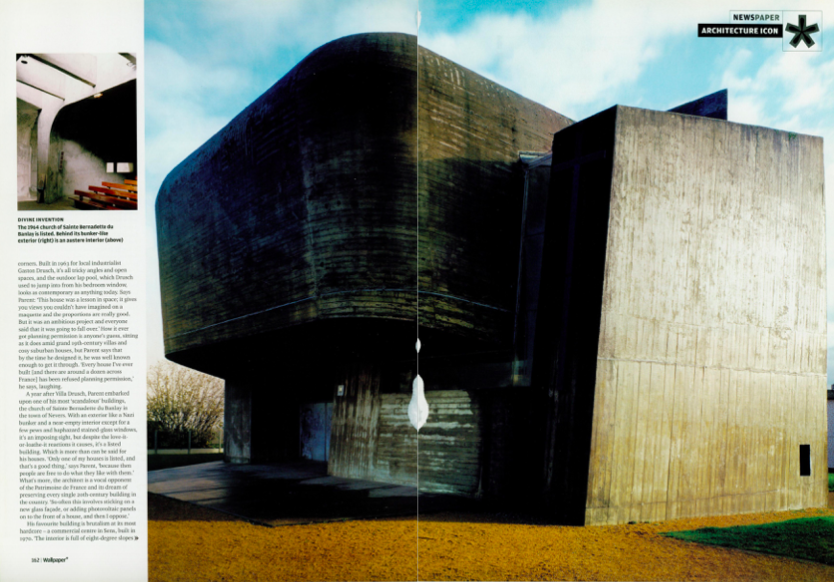

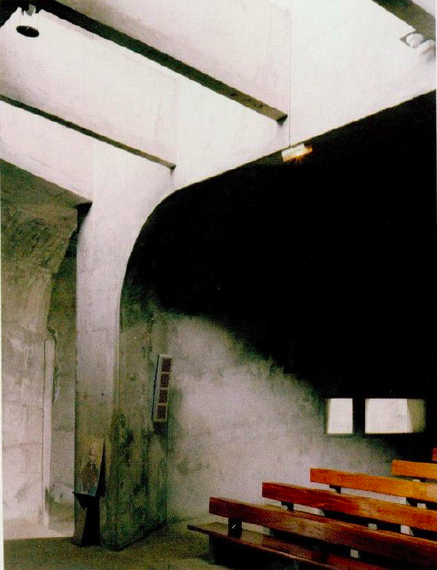

A year after Villa Drusch, Parent embarked upon one of his most 'scandalous' buildings, the church of Sainte Bernadette du Banlay in the town of Nevers. With an exterior like a Nazi bunker and a near-empty interior except for a few pews and haphazard stained-glass windows, it's an imposing sight, but despite the love-it-or-loathe-it reactions it causes, it's a listed building. Which is more than can be said for his houses. ‘Only one of my houses is listed, and that's a good thing,' says Parent, ‘because then people are free to do what they like with them.' What's more, the architect is a vocal opponent of the Patrimoine de France and its dream of preserving every single 20th-century building in the country. ‘So often this involves sticking on a new glass façade, or adding photovoltaic panels on to the front of a house, and then I oppose.'

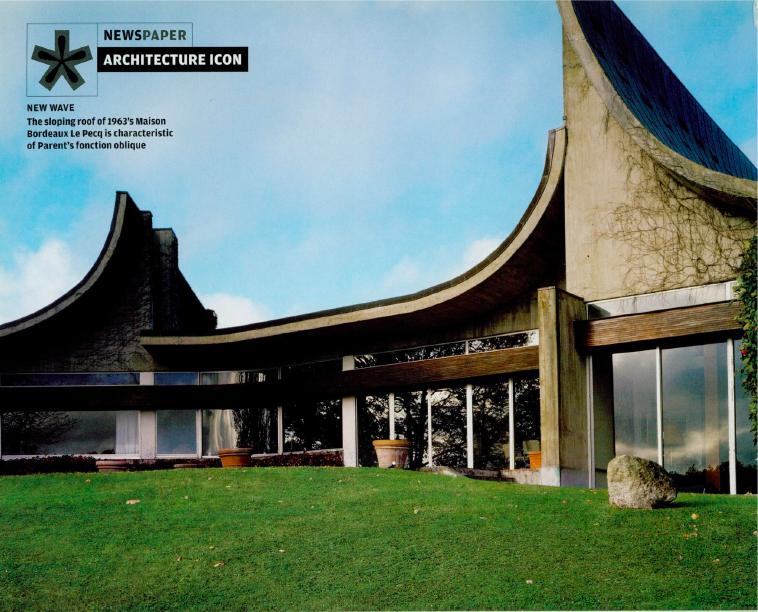

Spread from Wallpaper's 2007 article on Claude Parent, showing Maison Bordeaux Le Pecq

His favourite building is brutalism at its most hardcore – a commercial centre in Sens, built in 1970. ‘The interior is full of eight-degree slopes the fonction oblique,' he says, ‘but the mayor wants to pull it down.' He also built a stunning Mediterranean villa that tumbles down a cliff in th e millionaires' Mecca of Cap d'Antibes. Known as Villa Bloc, it was named after its owner, sculptor and writer André Bloc, who founded L’Architecture d'Aujourd'hui magazine and was a kingpin of the creative scene, hanging out with the likes of Fernand Léger, Sonia Delaunay and Parent.

Another example of Parent's work is an amazing house in Bois le Roy, a nondescript Normandy village about an hour outside Paris. With its sloping pagoda-like roof, the house rises out of a stunning ten-acre site; inside, it consists almost entirely of one large open space, with a small kitchen, bathrooms and bedrooms off it. He created the house in 1963 for a formidable art patron called Andrée Bordeaux Le Pecq, who wanted it as her countryside studio and designed most of the interior herself. Today, it belongs to the deceased owner's son, who lives in LA, and is empty most of the year. He is trying to sell it, but it is seen as an oddity by most, except for the architectural avant-garde.

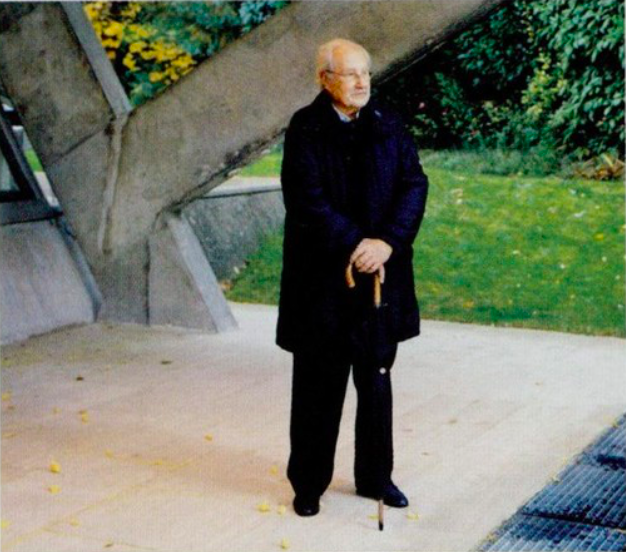

These days, Parent spends his time drawing fantasy buildings displaying his fonction oblique, satirical cartoons and working the lecture circuit. He lives with his wife in an immaculate apartment in a concrete block he designed in Neuilly in the 1960s. Now 84, he still cuts a debonair figure, with a fine moustache and a hat, although he has swapped the white Bentley for a Smart car.

Next year, Palais de Chaillot is mounting a retrospective of his work. ‘After that I can call it a day,' he chuckles. For his 80th birthday, his daughter gave him a monograph consisting of accounts of him written by 50 great architects, among them Frank Gehry, François Roche, and Jean Nouvel, who worked at his office for five years. Parent reminisces: ‘His desk was dirty, his fingers were stained and he drew like a pig, but you could see he was a petit génie.' Nouvel writes in the book: ‘You precipitated my heading out to sea… I could have, should have, drowned, but you didn't think so. Strengthened by this confidence, I didn't either... I owe it to you.'

A version of this article first appeared in the April 2007 issue of Wallpaper* (W*161)

Claude Parent, shot for Wallpaper* in 2007

Wallpaper* magazine spread, showing Parent's church of Sainte Bernadette

Detail from the interior of the church of Sainte Bernadette in Banlay

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Emma O'Kelly is a freelance journalist and author based in London. Her books include Sauna: The Power of Deep Heat and she is currently working on a UK guide to wild saunas, due to be published in 2025.