The former home of late architect Arthur Erickson faces an uncertain future

The late great Arthur Erickson, Canada's most renowned architect, was a jetsetter and a world traveller. He had an impressive list of international clients and hobnobbed with the likes of Pierre Trudeau, Margot Fonteyn and the Royal Family. But the place in his native Vancouver he called home - now under threat unless sufficient funds are raised to ensure its restoration - was a relatively understated abode in a bucolic, residential neighbourhood, where raccoons and sparrows were just as likely to turn up as any grander visitors.

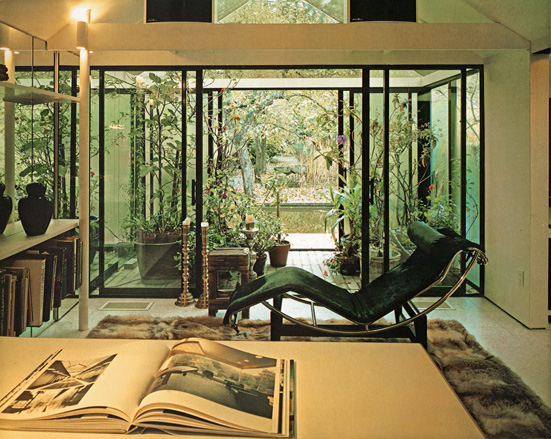

A converted garage on a double lot he purchased in 1957, and transformed into an elegantly executed contemplative space, was really more of an appendage to his rather extraordinary garden.

Although his garden parties were legendary, 4195 West 14th Avenue was above all a sanctuary for Erickson, who would return from LA or Baghdad and stay cocooned in his small green paradise, contemplating his next project.

Simon Scott, an architectural photographer who worked with Erickson and is a director of the Arthur Erickson Foundation, remembers in the late 1970's, when Erickson began designing projects in the Middle East, 'Gulf sheikhs pulling up in big black limousines and being astounded at the simplicity of his home.'

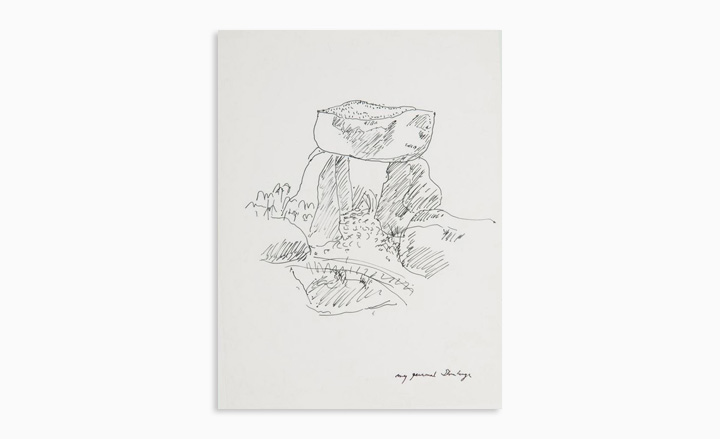

And yet the 90 sq m house and 650 sq m garden are seminal to understanding Erickson's work; glimpses of his buildings can be seen at every turn in tiny, micro gestures - a raw concrete leg of a garden bench that recalls a wall at his magnificent Simon Fraser University, or the pond with moon viewing platform that resonates with water elements at the Museum of Anthropology. A chrome-plated, mirror-like post inside his residence brings to mind his steel heavy Eppich house, while tendrils of ferns dripping over a kitchen skylight evoke his use of light and greenery at his Robson Square courthouse.

This is where it all began, where his ideas and sketches were born and even where deals were made, performances hatched and celebrations had. Margaret Mead did a reading here, Rudolf Nureyev danced in the garden around a pond filled with black swans, as Erickson and his life partner Francisco Kripacz remained impeccable if eccentric hosts to a moveable feast of artists, designers, writers, actors and politicians.

And yet, despite Erickson's iconic status as Canada's answer to Frank Lloyd Wright (who inspired a young Erickson's move from painting to architecture), the historic house and garden remain in jeopardy. Unless funding is found for a necessary million-dollar restoration and the mortgage (paid to a private lender after Erickson was forced into bankruptcy in 1992 and the bank put the property up for sale), the large double lot could end up bulldozed and transformed into a lucrative residential development.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

As Vancouver's residential real estate prices continue to be amongst the highest in the world, there are new pressures on this small footprint wonderland that housed Canada's finest modernist.

Liz Watts, a landscape architect and board member of the AEF, helped sound the alarm when the Erickson property was put up for sale in 1992. Watts, who lives a few blocks away, was told by a local estate agent that an intriguing double lot property was on the market. 'When I discovered it was Arthur's house I was shocked,' she recounts. 'I remember an agent speaking to a potential buyer on his mobile phone saying "yes of course the trees are a problem but they can all be cleared."'

Watts galvanized a group of local designers and gradually with national media exposure and the assistance of cultural heavyweights like Phyllis Lambert, current head of the CCA (Canadian Centre for Architecture) and chair of the AEF, stopped the house and garden from being sold.

But after Erickson's death in 2009 and a restructuring of the foundation to include his wider legacy, a renewed emphasis has begun on securing national heritage status for 4195 West 14th and on paying off the still onerous mortgage. 'Even with heritage status, there's still no guarantee of preservation,' notes Watts.

Phyllis Lambert notes that in Montreal, Moshe Safdie's apartment built for Expo 67 has heritage status, but that British Columbian provincial law is less aggressive about protecting modernist architecture.

And while Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin West has become a teaching facility/office/museum, Erickson's old abode remains vulnerable.

Still, its value as an historical cultural landscape remains undeniable. Entering the place, hidden by towering cedar hedges, laurel and fir, through an unassuming wooden side gate - is like walking into Erickson's mind.

As you come inside, you notice the little house to the North, its back to the laneway, but the big reveal is the garden. It unfolds with a Japanese sense of amplified space, often unfurling itself in a shape and scale-shifting manner.

To make the space feel larger than it was, Erickson used the trick of layered horizontal lines - a common one in Asia where the architect spent much of WWII working for British intelligence and preferring long conversations with Japanese POW's about Zen to actual interrogations.

And the garden - filled with many native plants that Erickson sourced himself from riverbanks and nurseries - exemplifies the concept of wabi sabi, the merging of the rough and the smooth, the wild and the refined. A micro-climate, it features ten different species of bamboo, zebra grass, Himalayan Rhododendrons, planted persimmon trees and native fir, cedars and arbutus trees, their textures layered against one another to great effect.

With the original fussy English garden leveled by the architect, and a berm and pond thick with lily pads and ornamental grasses created, the genius loci of the place is really a kind of clearing in the forest; a celebration of West Coast wilderness with a Zen sensibility. As you walk along the clockwise circular path, framed views and contemplative spots reveal themselves like small green epiphanies.

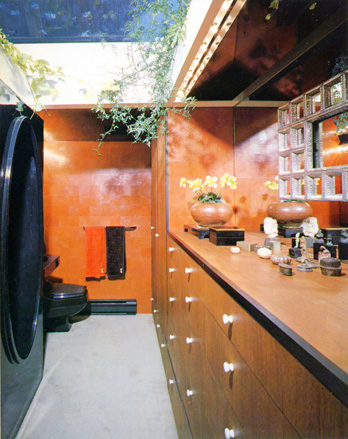

Inside the tiny house, a kind of wabi sabi is evidenced in the mix of materials: a simple wash of concealed incandescent lighting illuminates living room walls covered in sumptuous beige suede, Thai silk adorns walls sitting on a primitive wood foundation, and in the bathroom a black fiberglass shower stands opposite mahogany cabinets and leather clad walls. Erickson's tiny bed - a loft accessed via a childlike ladder- overlooks an arboretum that opens up to garden views and sits under a skylight with a silk covered baffle.

One can only imagine what sort of dreams he had in this place: ones that should rightly be preserved for Canada's next generation of architects, and not erased forever in the name of property values.

The Erickson house is now under threat unless sufficient funds are sourced to support its maintenance and restoration.

The converted garage was transformed by Erickson into an elegantly executed, modern contemplative space

The house and garden saw many famous guests, including Rudolf Nureyev.

The 650 sq m garden offers glimpses of the architect's work, with this bench recalling a wall at his magnificent Simon Fraser University.

The garden was just as important to Erickson as the house's interior.

Erickson's sketch of the garden pond's moon viewing platform

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yoursJean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

By Amy Serafin

-

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, UzbekistanThe legacy of modernist architecture in Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent, is explored through research, a new publication, and the country's upcoming pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; here, we take a tour of its riches

By Will Jennings

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

By Ellie Stathaki

-

How Le Corbusier defined modernism

How Le Corbusier defined modernismLe Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Frank Lloyd Wright’s last house has finally been built – and you can stay there

Frank Lloyd Wright’s last house has finally been built – and you can stay thereFrank Lloyd Wright’s final residential commission, RiverRock, has come to life. But, constructed 66 years after his death, can it be considered a true ‘Wright’?

By Anna Solomon

-

Why this rare Frank Lloyd Wright house is considered one of Chicago’s ‘most endangered’ buildings

Why this rare Frank Lloyd Wright house is considered one of Chicago’s ‘most endangered’ buildingsThe JJ Walser House has sat derelict for six years. But preservationists hope the building will have a vibrant second act

By Anna Fixsen

-

How to protect our modernist legacy

How to protect our modernist legacyWe explore the legacy of modernism as a series of midcentury gems thrive, keeping the vision alive and adapting to the future

By Ellie Stathaki

-

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st Century

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st CenturyThanks to a sensitive redesign by Studio Hagen Hall, this midcentury gem in Hampstead is now a sustainable powerhouse.

By Ellie Stathaki