Wall maker: Monica Bonvicini delves into architectural divisions

Since her storied, mid-1990s video installation Wallfuckin', Italian artist Monica Bonvicini's practice has focused on two rather unusual themes: walls and sex. An extensive survey of the Berlin-based artist's work at Baltic Contemporary in Gateshead combines the two.

‘Monica is keenly aware of how architectural settings give meaning. Be it to us, or to objects, or to art,’ explains curator Laurence Sillars. ‘She’s always thinking about how associations shift according to how things are exhibited.’ This explains the labyrinthine display that overwhelms the museum's third floor. Bonvicini has not only filled the room with artworks (many of which are newly commissioned) but she has designed and constructed the space in which they're seen.

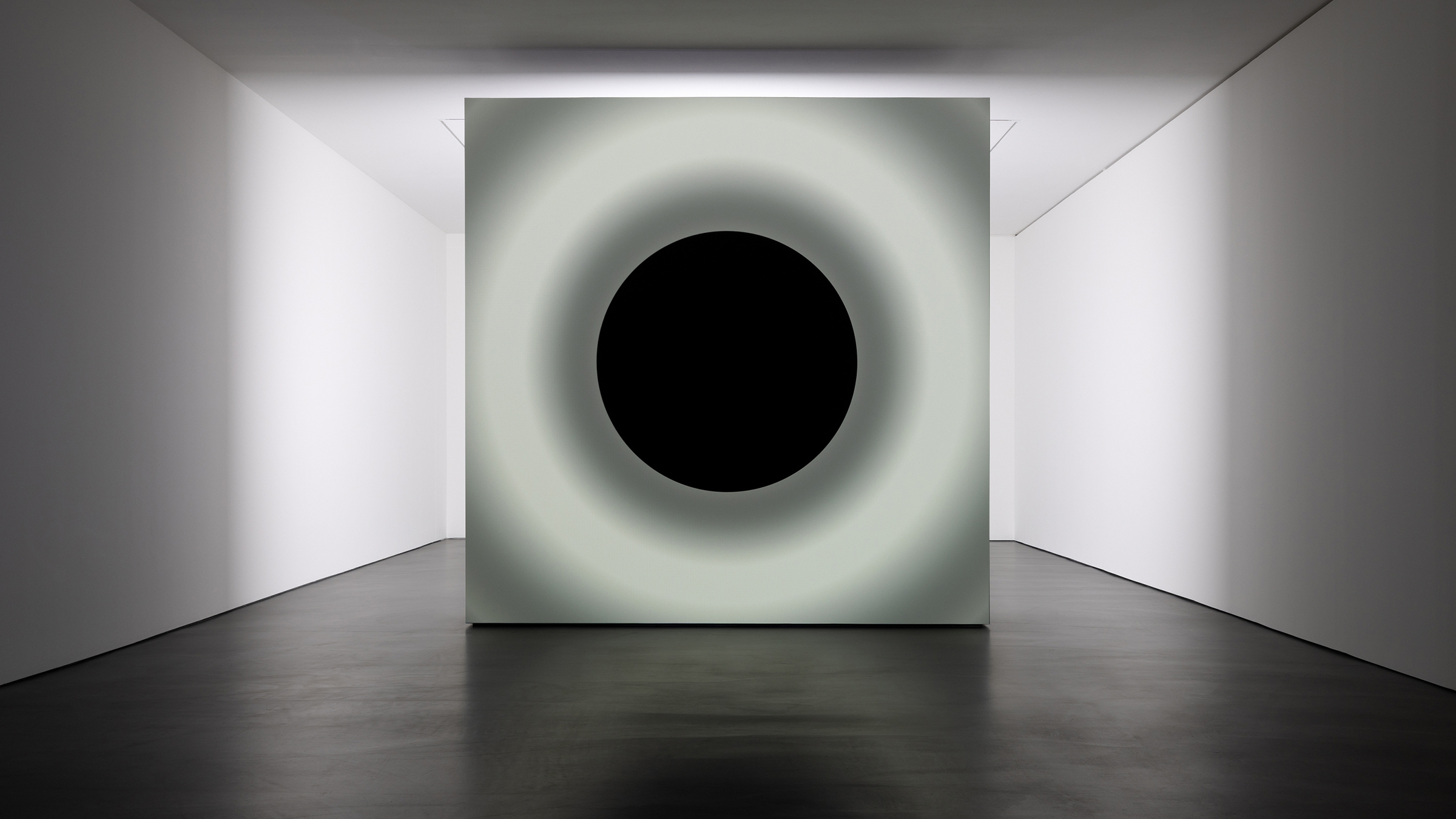

’Satisfy Me Flat’, 2009. Photography: John McKenzie. Courtesy of Baltic

Viewers are initially confronted by a vast unfinished wall, with marker-pen graffiti doodles scrawled on the bare backboards. It’s unclear which direction to turn – as if you’ve accidently stumbled into a construction site, as yet unfit for public view. 'It was a conscious design decision of Monica's to keep the maze walls raw,' Sillars explains. 'You can see that the environment you’re about to enter is a fabrication.'

This preoccupation with construction and the process of building is underlined by the first artwork we clap eyes on – an extensive series of plainly framed questionnaires. ‘They were given to people working on building sites without explanation – they were just left to fill them out as they see fit,’ Sillar explains. Questions include, 'Is construction work masculine?' and 'How do you get along with your gay colleagues?'. Answers range from shocking, to erudite to hilarious. The point is not to prove or disprove negative stereotypes of construction workers, but to 'tease out ideas surrounding eroticism and homosexuality’.

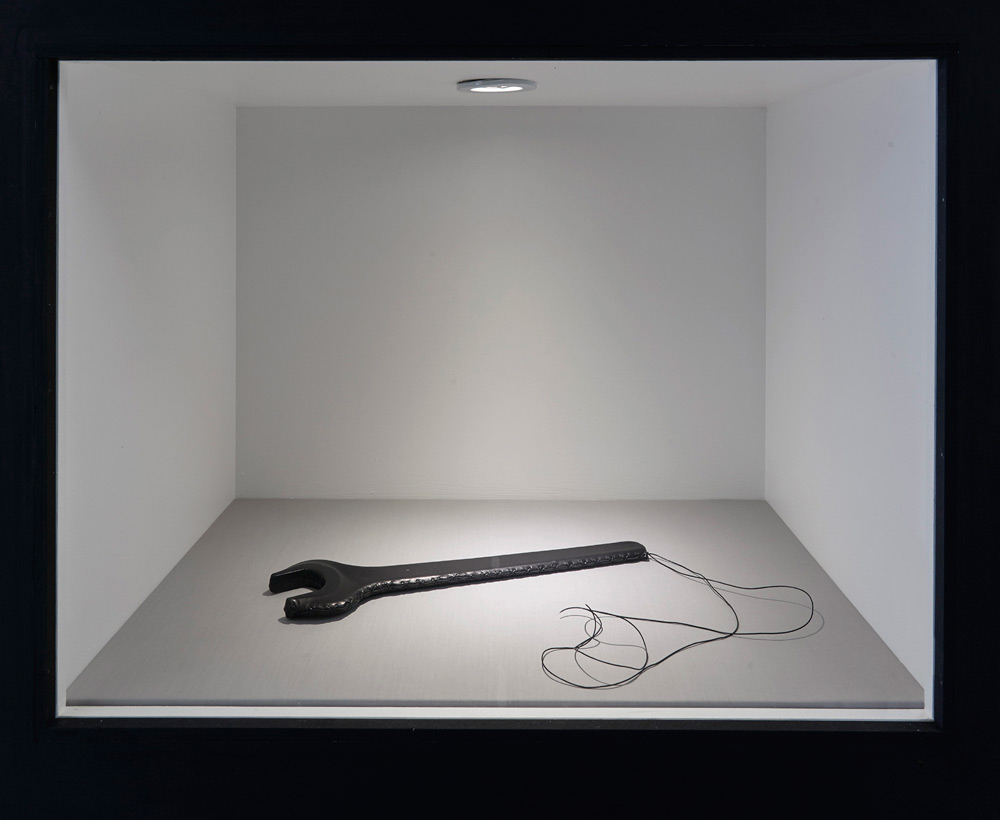

’Leather Tool (wrench)’, 2009

With these thoughts well and truly embedded in visitor's minds, the 'teased out' eroticism is allowed to run wild throughout the rest of the display. Leather-clad axes, tools and belts are framed by glass cases, inside constructed rooms. Visitors are voyeurs; peeping-toms through windows and door frames. At the end of one corridor, the words 'SATISFY ME' are printed across a minimalist black table, in a seductive headline. Elsewhere, squares of black shag-pile carpets delineate different domestic settings – bedroom, hallway and living room, where a perspex dildo stands tall, celebratory, on a white pedestal.

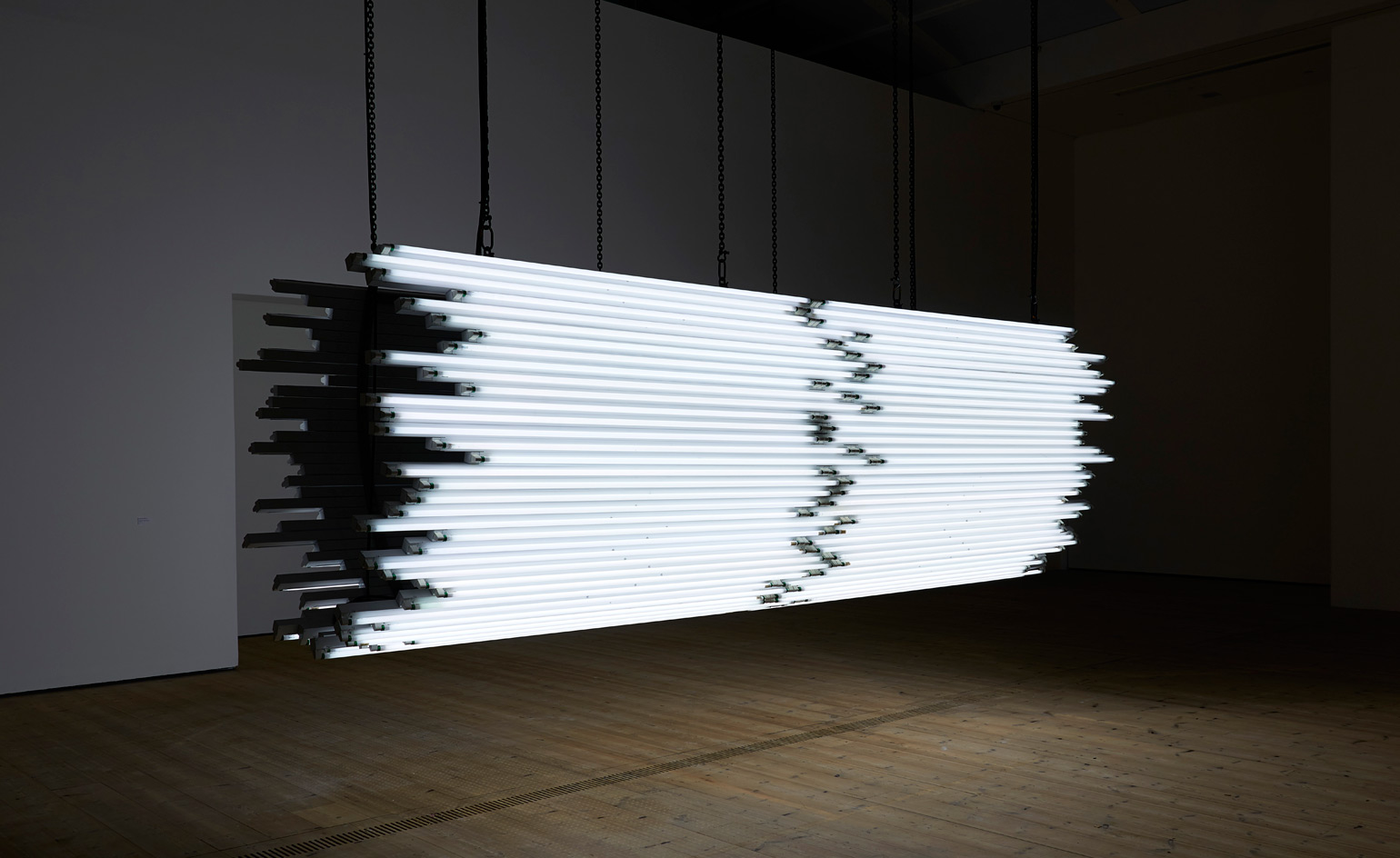

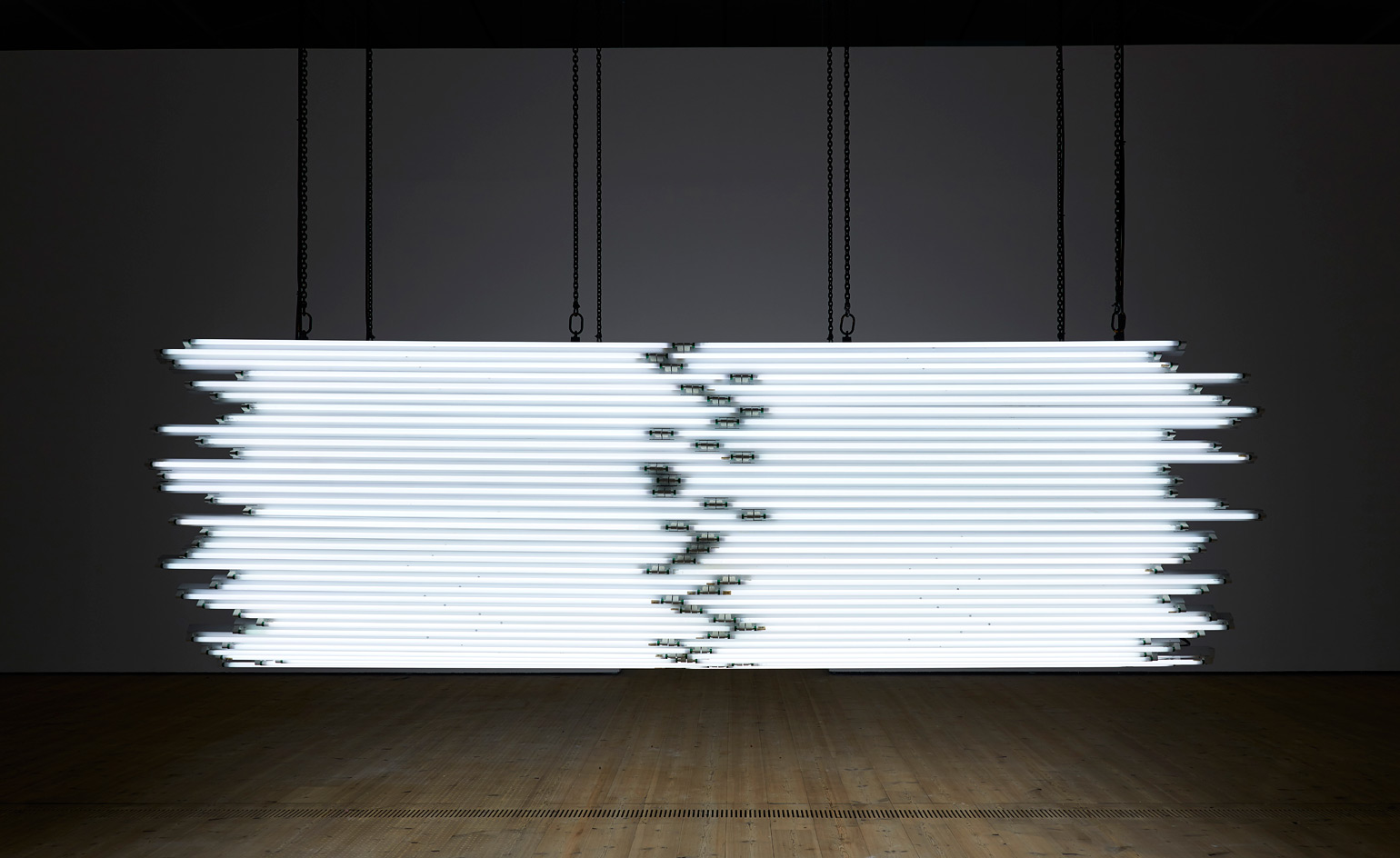

Upstairs, in the exhibition's concluding half, gone are the maze-like webs of walls, the dark carpets, erotic objects and kinky tableaus. Enclosed, claustrophobic intimacy is replaced by a vast, open space. Viewers are instead confronted by a wall of a different kind – an impenetrable wall of light. Light Me Black (2009) is the most visually arresting piece on display. Hung from the ceiling, comprising industrial strip lights and originally created for the Art Institute of Chicago, ‘the light tubes are the same fittings used in the museum's backstage areas and offices', Sillars informs. 'Monica often uses native bits of its architecture in the artworks.’

Light My Black, 2009. Photography: John McKenzie. Courtesy of Baltic

She has continued this tradition throughout the rest of the warehouse-like space. The Baltic is a converted flour mill, and Bonvicini has capitalised on the opportunities this affords in the strategic placement of her works. New monochrome paintings are suspended between six structural columns.

Whether architectural divisions are inherently good, bad or ugly doesn't seem to be Bonvicini's concern. She's more interested in the effect these walls have on the acts going on in between them. With chants of 'Build the wall' still reverberating around global news outlets, now seems like the perfect time to think a little more deeply about the philosophy behind building partitions, and what bricks and mortar actually mean for the people left on either side.

Light My Black, details, 2009

Left: Wave This Way, 2016. Right: That Hangs, 2009

Leather Tool (small bent axe), 2009

Left: That Hangs, 2009. Right: All The World's Futures, 2015

Chain Leather Swing, 2009

INFORMATION

’Monica Bonvicini: her hand around the room’ is on view until 26 February 2017. For more information, visit the Baltic website

ADDRESS

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Baltic

Gateshead NE8 3BA

Elly Parsons is the Digital Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees Wallpaper.com and its social platforms. She has been with the brand since 2015 in various roles, spending time as digital writer – specialising in art, technology and contemporary culture – and as deputy digital editor. She was shortlisted for a PPA Award in 2017, has written extensively for many publications, and has contributed to three books. She is a guest lecturer in digital journalism at Goldsmiths University, London, where she also holds a masters degree in creative writing. Now, her main areas of expertise include content strategy, audience engagement, and social media.

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installation

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installationIn Antarctica, Kyiv-based architecture studio Balbek Bureau has unveiled ‘Home. Memories’, a poignant art installation at the remote, penguin-inhabited Vernadsky Research Base

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensation

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensationAt Esther Schipper gallery Berlin, artists Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen draw on the elemental forces of sound and light in a meditative and disorienting joint exhibition

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design AwardsBrain Forest Quipu, Cecilia Vicuña's Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern, has been crowned 'Best Art Installation' in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceive

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceiveMichael Heizer’s City in the Nevada Desert (1972-2022) has been awarded ‘Best eighth wonder’ in the 2023 Wallpaper* design awards. We explore how this staggering example of land art came to be

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’Cerith Wyn Evans reflects on his largest show in the UK to date, at Mostyn, Wales – a multisensory, neon-charged fantasia of mind, body and language

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art lovers

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art loversAs London decks its halls for the festive season, explore our pick of the best Christmas installations for the art-, design- and fashion-minded

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeats

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeatsRafael Lozano-Hemmer brings heart and human connection to Miami Art Week 2022 with Pulse Topology, an interactive light installation at Superblue Miami in collaboration with BMW i

By Fiona Mahon

-

Textile artists: the pioneers of a new material world

Textile artists: the pioneers of a new material worldThese contemporary textile artists are weaving together the rich tapestry of fibre art in new ways

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith