'Still (the) Barbarians': Ireland’s Biennial of Contemporary Art goes global

As far as the cyclical nature of invasion, subjugation and colonisation goes, it’s a familiar tale in our species’ short history. When the Anglo-Normans invaded western Ireland in 1172, such was the direness of the natives’ situation that whole settlements were burned to the ground to prevent the invasion’s progress. When the area was finally captured, the invaders constructed a grand castle named for their ruler, King John, that presided dauntingly over the area on the banks of the River Shannon in what was to become the city of Limerick.

While today, the structure’s impressively preserved external walls and towers are a marvel to both scholars and tourists alike, the castle’s presence is an ancient reminder of the area’s history of invasion and oppression. It’s this subject matter that Koyo Kouoh, the curator of Ireland’s Biennial (referred to as EVA, short for Exhibition of Visual Art), has taken and explored via the medium of contemporary art, with the intention of encouraging dialogue within the artistic community around topics surrounding today’s postcolonial aftermath and scattered diasporas.

Entitled 'Still (The) Barbarians', after Constantine Cavafy’s 1898 poem 'Waiting for the Barbarians', the 2016 Biennial coincides with the important centennial of the 1916 Easter Rising, an armed insurrection mounted by Irish Republicans while Britain was occupied by the First World War. Kouoh’s background as the founding artistic director of Dakar’s RAW Material Company and curator of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair’s education programme makes the discussion a natural one, and she draws parallels between Ireland’s history of oppression at the hands of the British and today’s postcolonial narrative. ‘Ireland is the first and foremost laboratory of the British colonial enterprise, that was subsequently exported across the globe,’ she says.

Artists’ projects were selected through an open and invited call for proposals, and have been installed throughout the city, from the sprawling complex of a former condensed milk factory to the more accessible Limerick City Gallery of Art. London-based Ghanaian artist Godfried Donkor’s piece Rebel Madonna Lace displays a Limerick-made design of the artists’ own creation, inspired by the area’s history of lace production as well as symbols from the Ashanti people in Ghana. Accompanying mannequins are clad in a straitjacket and a fluorescent orange jumpsuit, recalling a penitentiary's finest, albeit woven from pretty commercially-produced lace in a striking visual representation of commercial enslavement as colonial legacy, while juxtaposing the city’s manufacturing heritage with the material’s status as a luxury item in Ghana.

Other artists were similarly direct in their engagement of the subject matter. Korean-American artist Michael Joo’s three-part installation This Beautiful Striped Wreckage (Which We Interrogate)... sets up shop at the city’s historical Sailor’s Home, a 19th century building stripped bare save for a few select pieces. His video projection of an emaciated Buddha from 3rd century Pakistan, filmed in the British Museum, is haunting and beautiful, but also a stark reminder of Britain’s unsavoury history of claiming ownership over that with which it has little association.

Latter-day variations on our species’ affinity for oppression and violence abound. Uriel Orlow’s work with microhistories brings Nelson Mandela’s incarceration on Robben Island into focus with the installation Grey, Green, Gold, which refers to the garden the prisoners were allowed, and one that concealed a manuscript of the biography that was to become 1995’s Long Walk to Freedom. A slide projection and wallpaper of the prison garden and the events surrounding it culminates in a tiny flower grown from a seed, which was renamed 'Mandela’s Gold' and symbolises a new era in post-apartheid South Africa.

Similarly, Canadian duo Public Studio’s film Road Movie has been staggered and projected onto sweeping screens in a vast factory space, depicting a system of segregated roads that have been built as part of the Israeli military control over the West Bank. There are roads for Jewish-Israeli settlers and roads for Palestinians – thus, the roads are commonly referred to as ‘Apartheid Roads’, underlining the continued occupation and modern-day colonisation of an intensely contested territory.

While the scope of engagement that EVA has produced in relation to discussions of colonial legacy is impressive, the engagement with the host nation as a departure point for this discussion – and particular the core centenary of the Easter Rising – has been less marked, something that Kouoh has acknowledged. The city is bidding for European Capital of Culture in 2020, with the Biennial a core part of its application, and while a few artists have put Ireland at centre stage – notably, Deirdre Power and Softday, as well as Jonathan Cummins and his complex trio of films – the mood is far more global in outlook, as the curator invites us to draw historical comparisons between far-flung regions like Southeast Asia and the Congo, and not merely in isolation.

‘The colonial enterprise from the Western Europe perspective was understood as a capitalistic and social project played out in faraway "uncivilised" societies as opposed to one played out next door,’ she replies when asked about Ireland’s modern relationship with its colonial past. ‘Ireland being geographically located in Western Europe makes it difficult to recognise that the country served as a laboratory of imperialism before its global expansion. Another may be that the extended duration of the British occupation of Ireland brought about a strong degree of assimilation, which finds its most visible expression in the contemporary situation of Northern Ireland divided between Unionists and Republicans.’

It’s an enormously complex subject to grapple with and as ever, one with deleterious aftershocks that reverberate through the fabric of the contemporary news cycle. ‘Europe cannot exonerate itself from the conduct and consequences of imperialism through denial and silencing,’ Kouoh concludes. ‘The current refugee crisis is just the tip of an iceberg of intricate and entangled fraught relationships forged during that era of massive exploitation. Their impacts continue to define our present day.’

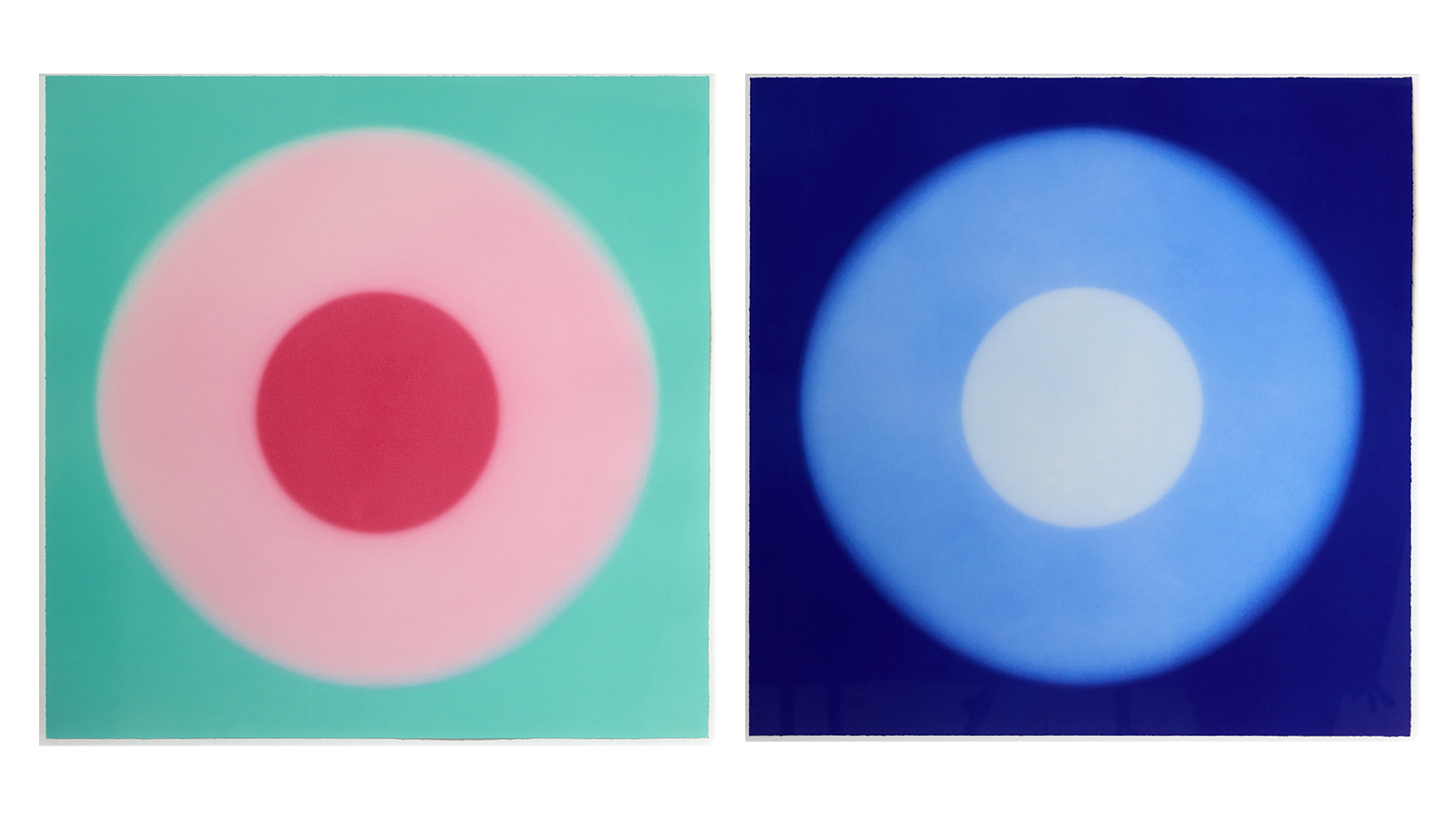

Entitled ’Still (The) Barbarians’, the 2016 Biennial coincides with the important centennial of the 1916 Easter Rising. Pictured: The Cloud, by Alfredo Jaar, 2015

Artists’ projects were selected through an open and invited call for proposals, and have been installed throughout the city. Pictured: Weights And Measures, by Bradley McCallum, from ’The Reversals’, 2014–15 Courtesy the artist, Robert Blumenthal Gallery and Eva International

London-based Ghanaian artist Godfried Donkor’s piece Rebel Madonna Lace (pictured) displays a Limerick-made design of the artists’ own creation, inspired by the area’s history of lace production as well as symbols from the Ashanti people in Ghana Courtesy the artist and Eva International

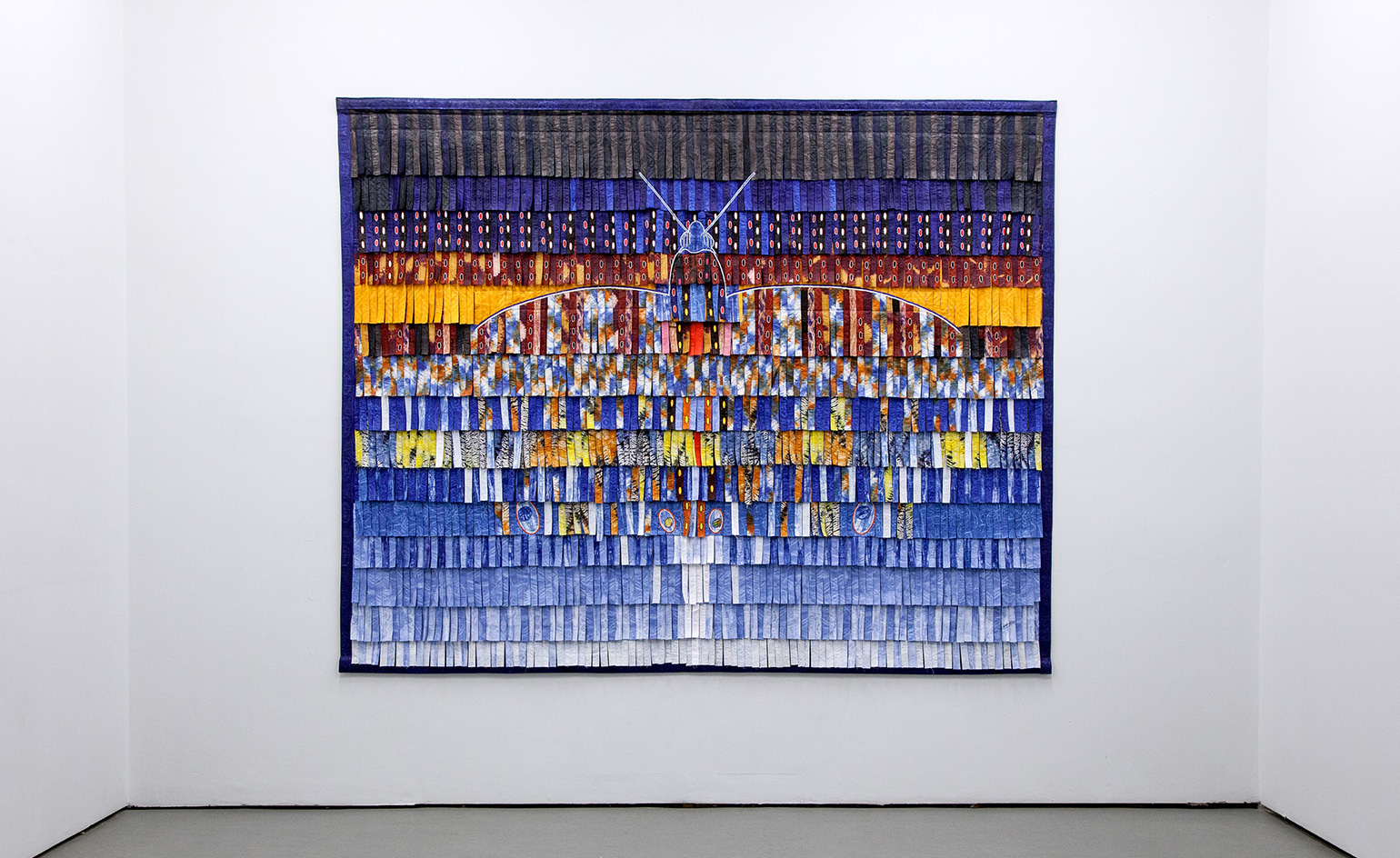

The city is bidding for European Capital of Culture in 2020, with the Biennial a core part of its application. Pictured: Le Papillon Bleu, by Abdoulaye Konaté, 2016. Courtesy the artist, Blain Southern and Eva International

The mood is far more global in outlook, as the curator invites us to draw historical comparisons between far-flung regions like Southeast Asia and the Congo, and not merely in isolation. Pictured: The Weight Of Scars, by Otobong Nkanga, 2015 Courtesy the artist and Eva International

INFORMATION

’Still (The) Barbarians’ is on view until 17 July. For more information, visit the EVA website

Photography courtesy EVA

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group show

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group showLismore Castle Arts’ ‘Each now, is the time, the space’ takes its title from John Cage, and sees four artists embrace the moment through sculpture and found objects

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

EXPO Chicago 2023 is an indoor-outdoor art extravaganza, from witches to unicorns

EXPO Chicago 2023 is an indoor-outdoor art extravaganza, from witches to unicornsAs the landmark 10th edition of EXPO Chicago kicks off, Jessica Klingelfuss explores the fair and this citywide art spectacle, from Derrick Adams’ unicorns to a witch-themed group show

By Jessica Klingelfuss

-

London Original Print Fair 2023: 10 prints on our radar, from Brian Eno to Tracey Emin

London Original Print Fair 2023: 10 prints on our radar, from Brian Eno to Tracey EminAs London Original Print Fair 2023 kicks off (until 2 April 2023), explore the 10 prints on our wish list this year, from Brian Eno to Tracey Emin; Mona Hatoum to Harland Miller

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Art Basel Hong Kong 2023: can the city’s art scene bounce back?

Art Basel Hong Kong 2023: can the city’s art scene bounce back?Art Basel Hong Kong 2023 is about to kick off following years of restrictions. Catherine Shaw explores what we can expect in and around this year’s fair (23-25 March 2023), and whether Hong Kong can bounce back to reclaim the title of ‘Asia’s art hub’

By Catherine Shaw

-

The most surreal moments in Art Basel history, from taped bananas to wealth-ranking ATMs

The most surreal moments in Art Basel history, from taped bananas to wealth-ranking ATMsAs a wealth-ranking ATM stole hearts and headlines at Art Basel Miami 2022, we look back on the most controversial moments in the history of Art Basel

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Miami Art Week 2022: your guide to the 6 best shows in town

Miami Art Week 2022: your guide to the 6 best shows in townAs Miami Art Week 2022 enters full swing, explore our preview guide to the highlights, from Art Basel Miami Beach 2022 art fair to the best exhibitions and events

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Artissima 2022: art exhibitions to see this weekend in Turin

Artissima 2022: art exhibitions to see this weekend in TurinTurin art fair Artissima 2022 spans the experimental and the perspective-bending; here’s what to see

By Martha Elliott

-

Paris+ par Art Basel: how the new art fair could transform Europe’s cultural identity

Paris+ par Art Basel: how the new art fair could transform Europe’s cultural identityWallpaper* Paris editor Amy Serafin explores the inaugural edition of Paris+ par Art Basel and speaks to key figures about what the new art fair will mean for Europe’s art scene

By Amy Serafin