Meet and seat: pulling up a chair with mid-century modern master Jens Risom

Jens Risom, photographed by Jesse Frohman at his home in New Canaan on 24 January 2008. Pictured right: Risom chairs (clockwise from front), '652W' armchair, with birch frame, for Knoll; 'U-140' armchair, white oak with yellow frame; 'C-160' armchair in American walnut, all from Rocket Gallery.

Last week, designer Jens Risom passed away at his home in Connecticut, seven months after celebrating his 100th birthday. To bid farewell to this dearly departed design hero and mark the Danish-American's centenary – a significant landmark in anyone's book – we trawled the Wallpaper* archives to bring you a vintage profile on the great man...

The seriously leafy, squeaky-clean Connecticut town of New Canaan, one hour from Grand Central by the Metro-North commuter railway, is reputed to be the richest small town in America. Behind the oaks, pines and plane trees, million-dollar, New England clapboard homes nestle discreetly on huge plots. Old money stockbrokers and entertainment glitterati alike appreciate the privacy that mutual affluence brings.

The town also happens to host the best collection of modernist homes on the eastern seaboard, thanks to the town’s adoption by the Harvard Five architects – Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, John Johansen, Philip Johnson and Eliot Noyes – in the late 1940s. Where once their glass and concrete constructions attracted outraged letters to the New Canaan Advertiser, now they are the focus of genteel restoration charities and well-padded heritage funds.

It is fitting, then, that New Canaan should be home to America’s last surviving design star from the mid-century furniture movement. Jens Risom, 91, but perky as an 80-year-old, lives in a modest bungalow stuffed with Danish expressionist art and chairs designed by himself, Arne Jacobsen and Risom’s former classmate Hans Wegner. He has lived so long that he is around to witness his rediscovery by a new generation of design aficionados.

Last year, Rocket Gallery in London held a retrospective of his work and many of his classic designs have recently been reissued by Ralph Pucci International. His chairs, meanwhile, are now in the permanent collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Yale Museum of Art & Design and the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, among others.

Born in Copenhagen in May 1916, Risom, whose father was an architect, remembers being interested in design from an early age. 'But I turned away from architecture because at that time the contractor and the client had power to change your designs. I always wanted to be in control.' Instead, after a period at a Danish business school, in the early 1930s he found work in Sweden, in 'the modernist shop in Stockholm.' He also did a stint in the design division of Stockholm’s leading department store, Nordiska Kompaniet, where he came across the furniture of Bruno Mathsson.

Risom’s time in Stockholm sparked an interest in furniture and he returned to Copenhagen in 1935 to study at the School for Arts and Crafts under Ole Wanscher and alongside fellow design icons-to-be Wegner and Borge Mogensen. He also studied under the great Kaare Klint who led the furniture school at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and who was a friend of his father. Risom puts this period of creativity in Denmark down to the country’s progressive educational and social systems. 'Good cabinet makers were educated very well in Denmark and didn’t want to just copy old models of furniture. They really latched on to the idea of good design as a way to be successful. Three of us in my class went on to operate as designers, but I don’t think we were aware of how unaware the rest of the world was of contemporary design. We were in a little nest of our own, 10 years before it started elsewhere.'

In 1939 Risom made his mind up to move to the US. 'I came to study developments in contemporary furniture design here, but discovered there wasn’t any to speak of. I was told there was no such thing as contemporary furniture design. Everyone was working from traditional English patterns – Chippendale was as contemporary as it got. But I decided it was better to be one of the first in a new, large market, rather than one of the many architects and designers in Denmark.'

Through MoMA contacts, Risom got freelance work designing textiles for the interior designer Dan Cooper and work began to come in, including an offer in 1940 to design the furniture for Collier's magazine House of Ideas, a model house designed by Edward Durell Stone at New York's Rockefeller Centre. Next came a bit of design synchronicity: in 1941 he met Hans Knoll, immigrant scion of a successful German furniture firm. 'Without knowing it, he was looking for me and I was looking for him. He was a wonderfully aggressive salesman, but he wanted to get into manufacturing quality furniture.' The two set out on a trip across America that, if they made biopics of furniture designers’ lives, would make for great coming-of-age road trip. They visited modernist architects and studied the market for new, clean-lined furniture.

The Knoll Furniture company was launched in 1942 with 15 pieces from the 20-piece catalogue designed by Risom. External circumstances dictated much of the design, as there were severe restrictions on using materials that might be needed for the war effort. There was no steel for springs and most wood was sequestered for aircraft production. Risom got around the restrictions by designing for surplus materials, such as the rejected parachute webbing that formed the supporting structure of his most famous chair, the Knoll '652W' armchair.

'Risom’s designs are crucial because they combine Danish tradition, with his embracing of early American modernism,' says Jonathan Stephenson, who curated the exhibition of his work at Rocket Gallery. 'It means his work is simple and streamlined, but with a great commitment to functionality and quality.'

Function is a theme that Risom repeatedly turns to in discussing his design philosophy. 'A designer has to have in mind function, comfort and construction. You start with the basic understanding of the function, is it a dining chair; an office chair – that needs to be like a throne with a high back to make the executive feel important; or a chair for relaxing in? Then you have to consider support, support for the body. A "soft" chair that you sink into feels good at first but after 20 minutes your back hurts. Design is not just visual. Design needs to be used by people and the different conditions of use determine a lot of the design.'

When Risom was 24 or 25 he met Frank Lloyd Wright. 'He said, "You do furniture. What do you think of my furniture?" His furniture was basically miniature versions of his buildings. Of course, his architecture is important to all of us, but his furniture was all at 90 degrees – everything was upright. I said "Couldn’t it be a bit more comfortable?" And he said: "Young man, the human body was created to stand up or lie down. Not to sit." I have a different view of the human body. Comfort is important and in design terms a chair has to look like it supports you. It has to look comfortable as well as be comfortable.'

After the launch of Knoll, Risom was drafted into the US army, where his language skills saw him used as a translator as the platoon moved through France and Germany. By the time he returned to the US after the war, Hans Knoll had married Florence Schust and she was taking on the role of design director for Knoll Associates. 'She was a devotee of van der Rohe and Saarinen. She didn’t like wooden furniture so much and my work got a lower billing,' says Risom. 'I realised she was going to set the policy and not favour my type of designs. Hans got upset when I left and we never saw each other again.'

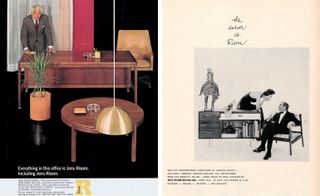

Jens Risom Design was launched in May 1946 with two full-time staff and eight pieces of furniture. 'People coming back from the war were easier to sell new designs to. Being in the army, they were used to the idea of new, modern equipment being better than old traditional equipment.' The company never made a loss, expanding every year, from a small Manhattan showroom, using sub-contractors to produce parts of furniture that Risom assembled, to having a 300,000 sq ft factory in Connecticut with showrooms worldwide. A big boost came in the early 1950s with an ad campaign shot by Richard Avedon using the uncompromising tagline: 'The answer is Risom'.

Unusually for a furniture designer, Risom controlled everything – design, manufacture and distribution. 'I was convinced we had to control manufacturing to control the quality,' he says. 'But I paid a price in terms of my reputation as a designer. Because I was a manufacturer I was “trade”, and down the scale from the pure designers, who worked for several companies.' In the 1960s he made a very successful move into office furniture, then in 1970 sold his company to the Dictaphone Corporation in order to concentrate on designing. A series of poor management decisions by a quick succession of new owners saw the company go out of business within a matter of years and the Risom name largely disappeared from furniture showrooms.

For his part, Risom feels he retired from the day-to-day running of his company too early, but then he wasn’t to know he would live into his nineties. Since the 1970s he has practiced freelance design, has joined the boards of design museums and been given countless honorary doctorates and awards. In 1996, he received the Danish Knight’s Cross. And on the eve of his 92nd year, he is still working, having designed a series of stools for the refurbishment of Johnson’s Glass House. Talking to him, you also get the impression that more important than any of this are his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

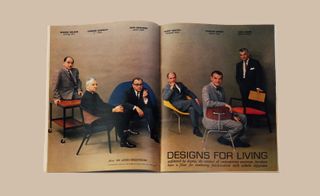

Once you enter your tenth decade, presumably your past can seem like another country. In his comfortable Connecticut home, Risom looks with bemusement at a photograph he has kept from a recent design magazine. It’s a reproduction of a shoot for Playboy, circa 1961, when the magazine got together George Nelson of Herman Miller, Edward Wormley of Dunbar Furniture, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Charles Eames and Risom for a double-page spread on the men 'revolutionizing furniture in America'. 'I suppose in a small way I am the grand old man of contemporary furniture design – because I am the only one left,' chuckles a very old, but very happy Mr Risom.

As originally featured in the April 2008 issue of Wallpaper* (W*109)

Risom (right) appeared in Playboy in July 1961, when the magazine got together George Nelson of Herman Miller, Edward Wormley of Dunbar Furniture, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Charles Eames and Risom for a double-page spread on the men 'revolutionizing furniture in America'

Risom's 'T-539' oak magazine table (front), from Rocket Gallery. Classic Risom bench with grey upholstery (back), part of a private collection.

Stack of three 'T-719' small side tables in steel and Formica; '1171' chair in walnut, all by Jens Risom, from Rocket Gallery.

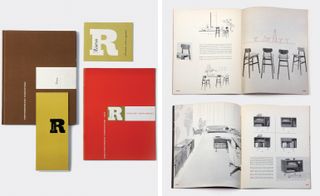

Risom's furniture catalogues and supplements from the 1950s were designed and illustrated by John Kanelous - whose wife just happened to be secretary to Richard Avedon, who, consequently, shot some of Risom's catalogue photography and an ad campaign

Risom's 1950s ad campaign with the slogan, 'The answer is Risom'

INFORMATION

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

For more information, visit the Rocket Gallery website

With special thanks to Rocket Gallery for the loan of furniture and printed material

ADDRESS

Rocket Gallery

4–6 Sheep Lane

London, E8 4QS

-

How Le Corbusier defined modernism

How Le Corbusier defined modernismLe Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

For a taste of Greece, head to this playful new restaurant in London’s Chelsea

For a taste of Greece, head to this playful new restaurant in London’s ChelseaPachamama Group’s latest venture, Bottarga, dishes up taverna flavours in an edgy bistro-style setting

By Sofia de la Cruz Published

-

Lucy Dacus on her Renaissance-inspired new album cover and intimate museum tour

Lucy Dacus on her Renaissance-inspired new album cover and intimate museum tourLucy Dacus' fourth album, 'Forever Is A Feeling', is an intimate exploration of love with visuals inspired by the romanticism of classical art

By Charlotte Gunn Published

-

Vincent Van Duysen ‘inspired by modernism’ for Molteni & C’s outdoor furniture debut

Vincent Van Duysen ‘inspired by modernism’ for Molteni & C’s outdoor furniture debutMolteni & C goes alfresco with two new collections and reissued classics, bringing its signature elegance to the great outdoors

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

First look inside Centurion New York by Yabu Pushelberg

First look inside Centurion New York by Yabu PushelbergCenturion New York is an expansive new space for American Express’ ‘black card’ members. Its interior designers Yabu Pushelberg give us a tour

By Tilly Macalister-Smith Published

-

Is this the most beautiful office in the world?

Is this the most beautiful office in the world?Parisian creative agency Art Recherche Industrie’s new HQ translates a 19th-century landmark into a chic open-plan office worth leaving home for

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Designer James Shaw’s latest creation is a self-built home in east London

Designer James Shaw’s latest creation is a self-built home in east LondonJames Shaw's east London home is Filled with vintage finds and his trademark extruded plastic furniture, a compact self-built marvel

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

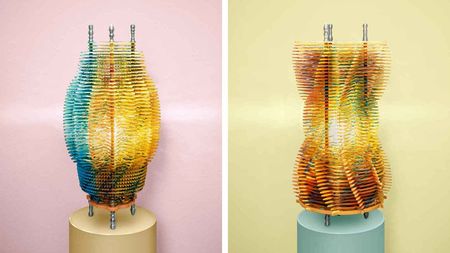

Taschen tantalises with new edition of Jorge Pardo’s ‘Brussels Lamps’

Taschen tantalises with new edition of Jorge Pardo’s ‘Brussels Lamps’German publishing house Taschen launches a limited-edition series of five ‘Brussels Lamps’ by Cuban-American artist Jorge Pardo

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Edra’s outdoor furniture is an ode to the sea

Edra’s outdoor furniture is an ode to the seaDesigned by long-term collaborator Jacopo Foggini, the ‘A’mare’ collection of outdoor furniture mimics shiny water, and was named 'Best Disappearing Act' at the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2023

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Peep inside Luca Nichetto’s Pink Villa in Stockholm, part studio, part showroom

Peep inside Luca Nichetto’s Pink Villa in Stockholm, part studio, part showroomWelcome to the pink house that is the new Stockholm home to Luca Nichetto's team

By Maria Cristina Didero Published

-

These papier-mâché lamps combine craft with sustainability

These papier-mâché lamps combine craft with sustainabilitySustainability and fine art are the driving inspirations behind ‘resolutely maximalist’ London lighting designer Rowena Morgan-Cox of Palefire

By Tilly Macalister-Smith Published