Desert architecture: modern buildings in arid environments

These manifestations of modern desert architecture reveal how design and material can combat the challenging climatic conditions of arid environments and extreme temperatures. Like the cactus and the camel, buildings must adapt to survive. From houses in Arizona, to research centres in Riyadh and installations in Jericho, we slip on some sand shoes and cross sub-tropical expanses to bring you the best of desert architecture.

King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center

Zaha Hadid Architects

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

This desert laboratory was designed by ZHA to make minimal energy demands in a region renowned for its extreme climate. Focused on a central research building, with angular prows that jut out across the landscaping, the architecture combines structural boldness with complex patterns on the walls and ceilings, giving the long Islamic tradition of geometric form a literal twist.

Writer: Jonathan Bell

King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center

Zaha Hadid Architects

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

The modular construction allows for future expansion, while covered outdoor circulation areas help mitigate the effects of solar radiation. Perhaps most notably, the building’s musalla (the open space outside a mosque) is the country’s very first prayer space to be designed by a woman.

Writer: Jonathan Bell

Swartberg House

Openstudio Architects

Karoo Desert, South Africa

Located near the Swartberg mountains on the edge of the Great Karoo desert in South Africa, this four-bedroom home was designed by Openstudio Architects. Built using local materials, the sturdy lodging embraces the diversity of its environment and encourages its inhabitants to exist in harmony alongside nature.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

Swartberg House

Openstudio Architects

Karoo Desert, South Africa

A passive temperature regulating system specified in the brief largely dictated the design. Huge openings with sliding timber shutters were built into the main living spaces, positioned to interact with the sun. The shutters are a shield from heat in the summer and a sun-trap in the winter, warming up the dense brick floors. Maintaining the traditional styles of the area, Openstudio employed local builders and used techniques typical of Karoo architecture, including brick-on-edge floors, roughcast lime-washed plaster walls and the outdoor dry stone wall which encloses the pool.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture

Snøhetta

Gharb Al Dhahran, Az Zahran, Saudi Arabia

Rising up from the eastern deserts of Saudi Arabia like an ancient rock formation, the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture is an ambitious piece of place-making. Nearly a decade in creation, this vast complex was designed by Norwegian firm Snøhetta to serve as a crossroads for many cultures, a geological form rendered in concrete and stainless steel.

Writer: Jonathan Bell

King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture

Snøhetta

Gharb Al Dhahran, Az Zahran, Saudi Arabia

The centre is broken up into five ‘pebbles’, smooth, shiny objects that glisten in the sun and appear mysterious and monumental on the horizon. A 98m tower is the dominant heart of the composition, with a smaller ‘keystone’ to one side and three lower, sleeker structures rising up out of the desert. Most visible of all is the facade’s ‘veil’, made up of approximately 360km of thin stainless steel pipe wrapped around the centre’s superstructure, and set above a Kalzip metal skin.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

Writer: Jonathan Bell

Three Gardens House

AGi Architects

Al-Funaitees, Kuwait

A family came to AGi Architects with the challenge of designing a house that would allow them to live outside 365 days a year, even in the midst of the Kuwaiti summer, when temperatures soar to over 40°C. Architects Joaquín Pérez-Goicoechea and Nasser Abulhasan – principals and founders of AGi – decided to use gardens to solve this request, weaving outdoor living into the fabric of the home while creating three spaces for different activities, times of the day and seasons.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

Three Gardens House

AGi Architects

Al-Funaitees, Kuwait

The architects examined the behaviour of the family to define the purposes of the outdoor spaces. ‘Due to the extreme Kuwaiti climate we decided to stratify the external uses according to the period of the year and the hours of the day in which these activities could be developed, and accordingly we designed three gardens,’ says Pérez-Goicoechea. By cascading the gardens and spaces across different levels, the designers used the architecture as a filter system, subtly delineating the private space for the family members and the more communal spaces for guests.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

Hidden Valley Desert House

Wendell Burnette Architects

Cave Creek, Arizona, USA

Sunken into a saguaro-studded knoll at Cave Creek in Arizona, this house by Wendell Burnette Architects, was designed to help its inhabitants pare their lifestyle back to basics. The simple construction entails a concrete plinth, topped with a mighty canopy equipped with mechanicals, energy supplies and water storage for the house. The plinth follows the contours of the land developing into a ‘thick’ cave at its lower end, and a shaded terrace at its upper end.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

Hidden Valley Desert House

Wendell Burnette Architects

Cave Creek, Arizona, USA

The Phoenix-based architects describe the house as a ‘long pavilion for living’. The clients requested a home where they could live simply alongside their collection of animals – birds, Koi fish, Rhodesian Ridgebacks and cat. The plinth is two thirds indoor and one third outdoor, always covered to create a shady space for living within the landscape.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

Stonematters

AAU Anastas and GSA research lab at ENSA Paris-Malaquais

Jericho, Palestine

In light of the decline of stone building in Palestine, where the material can be found in abundance, Bethlehem-based architecture practice AAU Anastas collaborated with the the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais to research and innovate stone building techniques by examining historic free-form stone vaults across Palestine. The Stonematters pavilion was born from this research and also part of an artists’ residency programme in Jericho.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

Stonematters

AAU Anastas and GSA research lab at ENSA Paris-Malaquais

Jericho, Palestine

The structure, which spans a surface area of 60 sq m, has been built entirely out of 300 interlocking stones that are mutually supported. Part of the challenge for the team was that the materials and techniques were locally sourced from the city of Jericho. For example, a polystyrene construction support was roughly cut in a local factory and transported to another factory for a robotic carving process, which determined the specific shapes of the ‘bricks’.

Writer: Harriet Thorpe

Shapeshifter House

Ogrydziak Prillinger Architects

Reno, Nevada, USA

San Francisco-based architect Luke Ogrydziak and his partner Zoe Prillinger were intrigued by the framing of the desert as ’a barren wasteland, a kind of "no place"’ when they started working on this family house in a residential suburb of Reno. The house, fittingly entitled Shapeshifter House, is situated in the desert landscape of Nevada, and at the same time draws on this soft, sandy topography, which heavily influenced its striking, origami-like forms.

Writer: Ellie Stathaki

Shapeshifter House

Ogrydziak Prillinger Architects

Reno, Nevada, USA

Spanning three generous levels, the house features a fairly traditional layout – despite its distinctly unconventional shape. The ground level is dedicated to a large, flowing living space that encompasses sitting, dinning and kitchen areas, as well as parking space and storage. A sculptural staircase leads up to the middle floor and a study, as well as one of the house’s bedrooms. The top level and its privileged views out towards the city and the surrounding expanse of untamed desert are set aside for the master bedroom, with its own walk-in wardrobe and en suite bathroom.

Writer: Ellie Stathaki

Tuscon Mountain Retreat

DUST

Tuscon Mountain Reserve, Arizona, USA

Placed delicately in its context, architecture firm DUST’s Tucson Mountain Retreat is situated on the outskirts of the lush Sonoran Desert, designed in direct response to its intriguing setting. The architects, who describe the project as being ‘rooted in the desert’, have created a striking rammed earth dwelling that makes minimum impact on its fragile environment. It seamlessly blends into the surrounding Arizona landscape, featuring elegant, clean lines and a minimalist aesthetic.

Writer: Sara Sturges

Tuscon Mountain Retreat

DUST

Tuscon Mountain Reserve, Arizona, USA

The internal programme is separated into three zones: living, sleeping and entertainment areas. These three areas occupy a different section of the structure and the visitor has to step outside one in order to enter the next. This gesture both allows a level of privacy between uses, and urges the inhabitants to be at one with the breathtaking desert landscape.

Writer: Sara Sturges

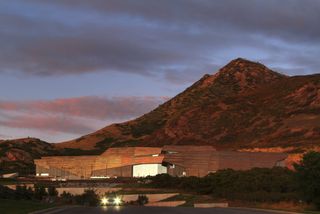

Natural History Museum of Utah

Ennead Architects

Salt Lake City, Utah, US

New York-based Ennead Architects Natural History Museum of Utah is located on the rugged edge of Salt Lake City. The $103 million, 163,000 sq ft Rio Tinto Center, as the building is called, in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains’ Wasatch Range, restates the stark beauty of the region’s topography – ’which is like no other in the world,’ says architect Todd Schliemann, who toured the state extensively before picking up his pen. With an aesthetic language of rugged elegance, the museum provides research and exhibition space, as well as – crucially – locating visitors within the natural world, and facilitating observation of it.

Natural History Museum of Utah

Ennead Architects

Salt Lake City, Utah, US

The design’s organic properties, which draw upon the elemental natural landscape, are effectively reinforced by Schliemann’s material palette: a board-formed concrete base, and some 42,000 sq ft of standing-seam copper paneling, a skin applied in horizontal bands expressive of stratified, mineral-rich mountain rock. Inside the building, the design centres around a spatial coup de theatre called ‘the Canyon’, a 60-ft-high atrium space, flooded with sunlight and bridged by circulation walkways.

Element House Hotel

MOS Architects

Anton Chico, New Mexico, USA

In an effort to restore the sense that we are living on a star amongst the stars, Star Axis, the Mayan-looking land art project and naked eye observatory in the New Mexican desert, took sculptor Charles Ross 40 years to almost-finish. Nearby Elements House is an autonomous visitors’ centre, designed by New York-based firm MOS for the Museum of Outdoor Arts as a quasi-hotel for visitors to Star Axis.

Writer: Shonquis Moreno

Element House Hotel

MOS Architects

Anton Chico, New Mexico, USA

Meticulously sited to deny visitors any direct views of the artwork, it is an exploded, irregular cluster of room-sized ‘houses’, with pitched roofs, chunky chimneys and aluminium panels shaped like roof shingles and brick or vinyl siding. It’s off the grid, modular design offers an alternative way to experience the site and features a structural insulated panel system that integrates on-site generation of energy.

Writer: Shonquis Moreno

Bosjes Hotel

TV3 Architects and Town Planners

Botha, Western Cape, South Africa

The old Bosjesman’s Valley Farm – a lush Eden of vineyards, olive and fruit trees, and proteas just an hour’s drive along the R43 from Cape Town – has been owned by the Botha and Sofberg families since the 1830s, though the property’s original Cape Dutch manor house dates back to 1790. TV3 Architects and Town Planners, and interior designer Liam Mooney have converted an outbuilding, an 18th century barn, a 19th century shed and a 1930s stables into a grand five-bedroom guesthouse swathed in sandy hues, chartreuse and copper.

Writer: Daven Wu

Bosjes Hotel

TV3 Architects and Town Planners

Botha, Western Cape, South Africa

The guesthouse makes the most of its bucolic setting – diversions range from swooping white curls of the chapel designed by Steyn Studio to rambling walks through gardens vibrant with plants and trees specifically mentioned in the Bible, such as myrtle, African Wormwood, white mulberries, and Eureka lemons.

Writer: Daven Wu

Toro Latin Kitchen and Bar restaurant

Arthur Casas

Cabo San Lucas, Mexico

At the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula, Brazilian architect Arthur Casas frames the views of the Pacific Ocean and the arid desert vegetation through an unobtrusive rectangular timber frame. The ideal of the traditional adobe – all earth-tones, twig pergolas, straw ceilings and timber rafters, rustic wooden cabinets and flower boxes – is quietly countered by modern notes like Corten steel beams, ceramic pots lined up on shelves suspended on steel cables, and classic furniture by Luis Barragan and Clara Porset.

Writer: Daven Wu

COP22 Village

Oualalou+Choi

Marrakech

For two weeks in November 2016, over 40,000 delegates from 195 countries met in the COP22 village, a mix of temporary structures which were spread out over 30 hectares of land on the southern edge of Marrakech for the UN Climate Change Conference. Using locally-sourced materials, Oualalou+Choi’s design reflected the climate summit’s focus on sustainable development, and at the same time incorporated local architectural traditions in new ways.

Writer: Mary Pelletier

COP22 Village

Oualalou+Choi

Marrakech

Inside the village, a series of verandas, patios and atria with accessible rooftops reflected the rural architectural traditions of Morocco. Named ‘agora22’, the structure housed two restaurants and functioned as communal meeting spaces for delegates, where they could chat comfortably outside of the formal meeting sessions. In keeping with the summit’s recyclable remit, ‘agora22’ was comprised almost entirely of reusable particle board, down to the tables and chairs, all of which will be dismantled and reassembled for future projects.

Writer: Mary Pelletier

C.I.D Interpretation Center

Emilio Marin

Atacama Desert, Chile

Expansive, arid and unrelenting, Chile’s Atacama desert is undeniably beautiful, making it one of the country’s chief tourist destinations. To help lure and orientate tourists to the region, Emilio Marín and Juan Carlos López designed a visitors’ centre as part of the infrastructure for the wind farm. The architects describe the project in terms of the relationship between landscape and architecture. Six ‘wings’ – perhaps better understood as petals arranged around a central core – form wedge-shaped structures, linked by an internal corridor but reading as an abstracted series of forms from a distance, united by the common cladding material.

Writer: Jonathan Bell

C.I.D Interpretation Center

Emilio Marin

Atacama Desert, Chile

While the structure might appear stark and raw, with its deliberate juxtaposition of angles, shadow and unrelenting colour, it sits as lightly on the ground as possible, with a natural ventilation system focused on the internal courtyard. In the cold winter months, the large windows make the most of solar heating. Most importantly of all, the building is designed to go completely dark at night.

Writer: Jonathan Bell

Pobble House

Guy Holloway Architects

Dungeness, Kent, UK

This home stands alone within Dungeness’ sparse headland, hovering in the eerie landscape famed for its unique architecture. As dictated by local planning policy, the building (built on the site of an older structure) takes its cue in scale and proportion from its predecessor. Three simple forms – clad in larch, Corten steel, and cement respectively – define the house’s volumes and add character, skewered by a long corridor that organises the space inside. As the architects explain, this axis is ’aligned perfectly’ with the nearby lighthouse, leading from the living space to the bedrooms while funnelling views out over the expansive nature.

Writer: Emma Blundell

Pobble House

Guy Holloway Architects

Dungeness, Kent, UK

Once inside, the visitor’s gaze is always drawn to the outdoors. The large open-plan kitchen and living space features a glazed sliding door that fully disappears in concealed wall pockets when open. A long horizontal window frames the power station. Discreet bespoke furniture lines the interior, carefully designed to avoid detracting attention from the views and enabling the home to ‘open up to the landscape’.

Writer: Emma Blundell

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

The moments fashion met art at the 60th Venice Biennale

The moments fashion met art at the 60th Venice BiennaleThe best fashion moments at the 2024 Venice Biennale, with happenings from Dior, Golden Goose, Balenciaga, Burberry and more

By Jack Moss Published

-

Crispin at Studio Voltaire, in Clapham, is a feast for all the senses

Crispin at Studio Voltaire, in Clapham, is a feast for all the sensesNew restaurant Crispin at Studio Voltaire is the latest opening from the brains behind Bistro Freddie and Bar Crispin, with interiors by Jermaine Gallagher

By Billie Brand Published

-

Vivienne Westwood’s personal wardrobe goes up for sale in landmark Christie’s auction

Vivienne Westwood’s personal wardrobe goes up for sale in landmark Christie’s auctionThe proceeds of ’Vivienne Westwood: The Personal Collection’, running this June, will go to the charitable causes she championed during her lifetime

By Jack Moss Published