Data centre architecture and innovation explored in London exhibition

‘Power House: the architecture of data centres’ is a new London exhibition exploring the design of these often overlooked, but increasingly commonplace infrastructure buildings

‘Power House: the architecture of data centres’ is a London exhibition (3 November 2021 – 28 February 2022) about a critical and increasingly commonplace type of building, albeit one that remains out of sight for the vast majority of the world’s population. The data centre is now utterly integral to modern society, emerging as a crucial piece of infrastructure and industrial architecture that serves up everything from official secrets to selfies. As computing shifts decisively into the cloud, we are effectively untethered from hardware thanks to our reliance on these colossal structures and data centre architecture. For the end user, it all remains very abstract; we have no idea where our data is stored, let alone what kind of building houses the servers required to host it.

Data centre architecture explored

Retrofitted oil rigs by Arup. Created especially for the exhibition, this vision of an offshore cluster of data centres proposes re-using existing oil rigs, with cooling coming from the sea and the wind. According to the architects, the structures would be ‘circular, modular and sustainable, giving a new life to these abandoned sea giants'&

Contemporary data centre architecture comprises colossal structures, shaped by the need to provide space for thousands of pieces of equipment, together with the security, cooling, and redundancy measures required for smooth, seamless operation. These buildings are also extremely energy intensive; one of the stark statistics cited by the exhibition curators is that ‘a single Bitcoin transaction has the equivalent impact of watching 91,624 hours of YouTube’. They add that the internet generates around one billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions every year, thanks in part to the rapid spread of these new architectural archetypes.

Depending on its scale, a data centre can draw up to a hundred times more power than a comparatively sized office building, which is why ‘lights out’ centres are becoming more popular; remote, dark facilities that can run without any human intervention except for maintenance, to make for more sustainable architecture.

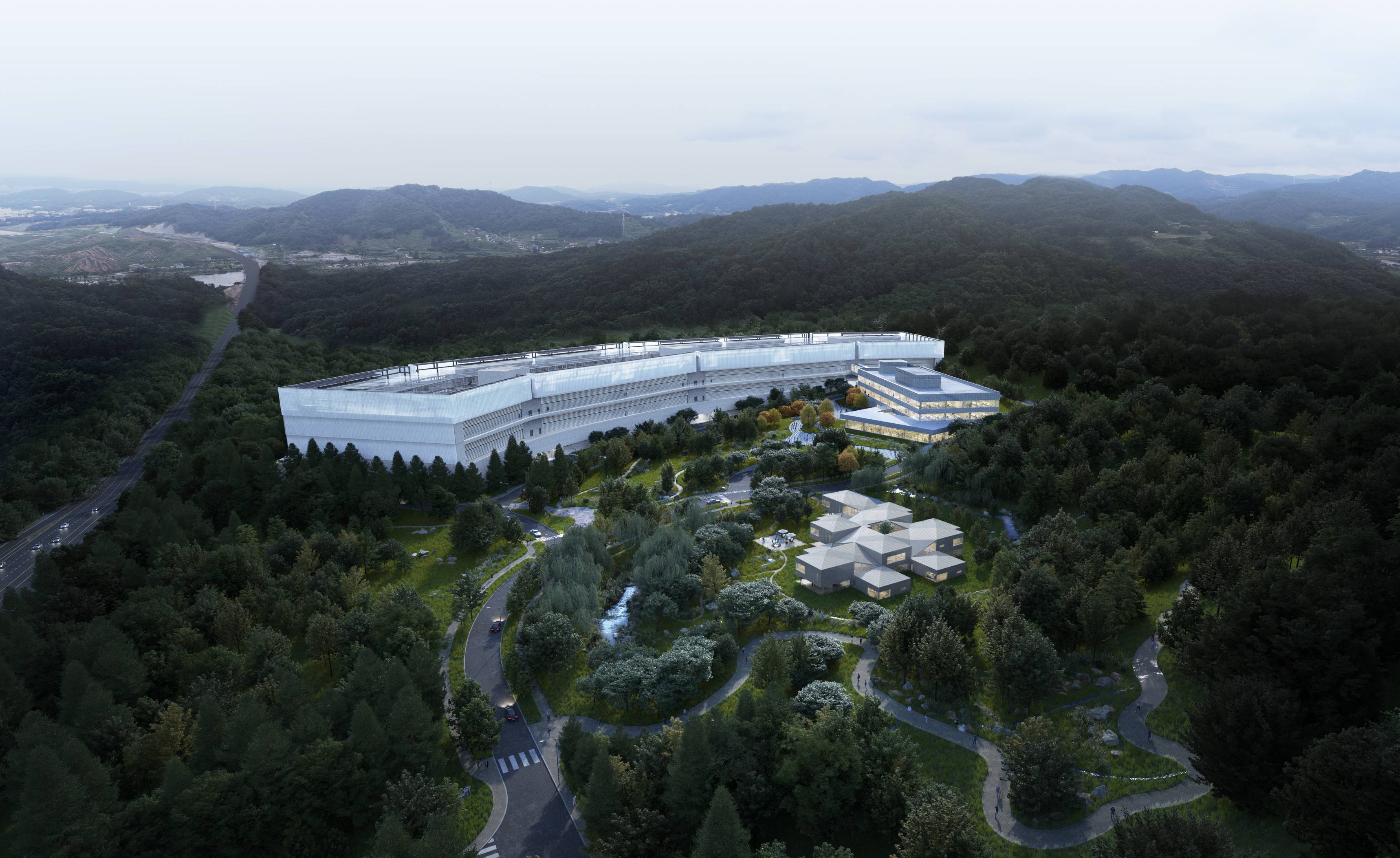

Gak Chuncheon Project by Kengo Kuma and DMP, Gangwon Province, South Korea. Completed in 2013, this data centre for Naver was designed by Kengo Kuma with DMP. A low-rise structure, it sits in the foothills of Mount Gubong and has been designed to allow for natural cooling

Clearly, we’re going to need more data centres, not fewer, so their visual and environmental impact is of paramount importance. ‘Power House’, on show at the Roca London Gallery, considers the evolving physical design of these decidedly non-human spaces. Curated by author and Walllpaper* contributor Clare Dowdy, the exhibition also has a focus on London’s data centres, overseen by Dezeen's Tom Ravenscroft. In big cities, these structures are often ‘hidden in plain sight’, with a corresponding absence of aesthetics. All too often, they’re the epitome of business park blandness, whether it’s for reasons of security or sustainability.

There’s no such coyness in many of the exhibits, which include completed structures, projects underway and conceptual ideas. ‘Data centres power modern life and yet they're rarely considered as pieces of architecture,’ says Dowdy. ‘As they mushroom across the globe, it's time we thought of data centres as a peculiar, and peculiarly challenging, new building typology.’

Qianhai Information Building by Schneider + Schumacher, Shenzhen, China. Designed by the German studio Schneider + Schumacher, the Qianhai Information Building in Shenzhen is the first high-rise data centre. Due for completion in 2023, the 16-storey tower has a roof garden for employees and a windowless façade bearing a binary representation of pi, designed to shimmer in the wind. At ground level, public facilities help integrate the structure into the cityscape

AM4 data centre by Benthem Crouwel Architects, Amsterdam. Built for American data giant Equinix as part of its portfolio of over 200 data centres around the world, AM4 is located in Amsterdam. Completed in 2017, the 12-storey building was designed by Benthem Crouwel as a modular structure that could eventually be repurposed. In addition, heat generated by the equipment is shared with other buildings on its Science Park site

INFORMATION

‘Power House: the architecture of data centres’ runs 3 November 2021 – 28 February 2022, Roca London Gallery, rocalondongallery.com

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Roca London Gallery

Station Court, Townmead Road, London, SW6 2PY

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Dive into Buccellati's rich artistic heritage in Shanghai

Dive into Buccellati's rich artistic heritage in Shanghai'The Prince of Goldsmiths: Buccellati Rediscovering the Classics' exhibition takes visitors on an immersive journey through a fascinating history

-

Love jewellery? Now you can book a holiday to source rare gemstones

Love jewellery? Now you can book a holiday to source rare gemstonesHardy & Diamond, Gemstone Journeys debuts in Sri Lanka in April 2026, granting travellers access to the island’s artisanal gemstone mines, as well as the opportunity to source their perfect stone

-

The rising style stars of 2026: Connor McKnight is creating a wardrobe of quiet beauty

The rising style stars of 2026: Connor McKnight is creating a wardrobe of quiet beautyAs part of the January 2026 Next Generation issue of Wallpaper*, we meet fashion’s next generation. Terming his aesthetic the ‘Black mundane’, Brooklyn-based designer Connor McKnight is elevating the everyday

-

Arbour House is a north London home that lies low but punches high

Arbour House is a north London home that lies low but punches highArbour House by Andrei Saltykov is a low-lying Crouch End home with a striking roof structure that sets it apart

-

In addition to brutalist buildings, Alison Smithson designed some of the most creative Christmas cards we've seen

In addition to brutalist buildings, Alison Smithson designed some of the most creative Christmas cards we've seenThe architect’s collection of season’s greetings is on show at the Roca London Gallery, just in time for the holidays

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom wineries-turned-music studios to fire-resistant holiday homes, these are the properties that have most impressed the Wallpaper* editors this month

-

A refreshed 1950s apartment in East London allows for moments of discovery

A refreshed 1950s apartment in East London allows for moments of discoveryWith this 1950s apartment redesign, London-based architects Studio Naama wanted to create a residence which reflects the fun and individual nature of the clients

-

David Kohn’s first book, ‘Stages’, is unpredictable, experimental and informative

David Kohn’s first book, ‘Stages’, is unpredictable, experimental and informativeThe first book on David Kohn Architects focuses on the work of the award-winning London-based practice; ‘Stages’ is an innovative monograph in 12 parts

-

100 George Street is the new kid on the block in fashionable Marylebone

100 George Street is the new kid on the block in fashionable MaryleboneLondon's newest luxury apartment building brings together a sensitive exterior and thoughtful, 21st-century interiors

-

Futuristic-feeling Southwark Tube Station has been granted Grade II-listed status

Futuristic-feeling Southwark Tube Station has been granted Grade II-listed statusCelebrated as an iconic piece of late 20th-century design, the station has been added to England’s National Heritage List

-

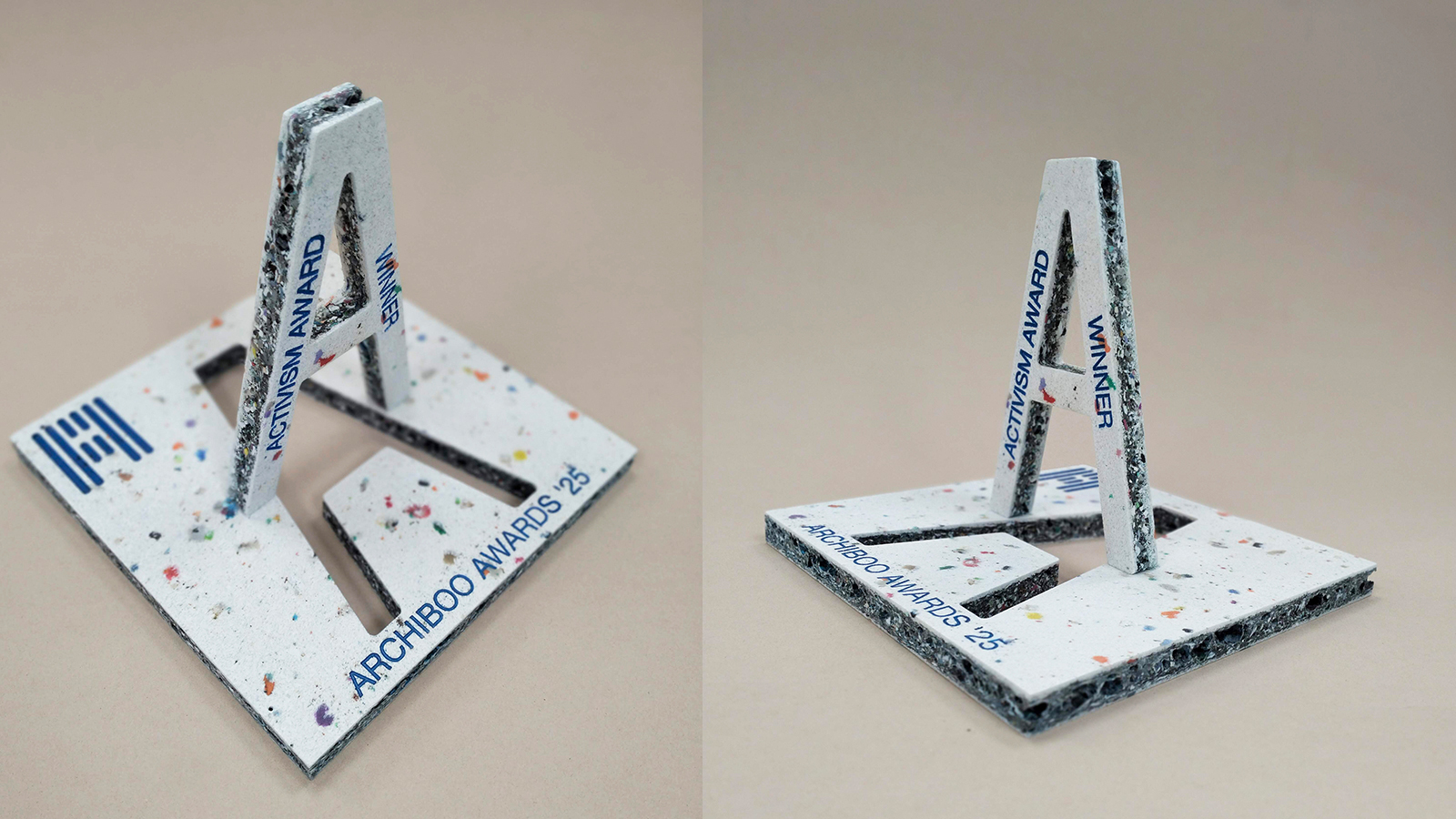

Archiboo Awards 2025 revealed, including prizes for architecture activism and use of AI

Archiboo Awards 2025 revealed, including prizes for architecture activism and use of AIArchiboo Awards 2025 are announced, highlighting Narrative Practice as winners of the Activism in architecture category this year, among several other accolades