Ben Aranda Q&A

Wallpaper*: How did the collaboration with Matthew Ritchie come about?

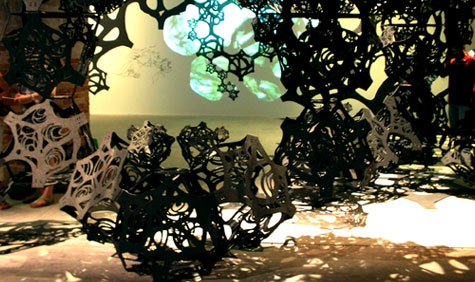

Ben Aranda: Matthew hatched an idea with the arts organization, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, to produce an “anti-pavilion,” a sort of ruined structure that would be a drawing at the scale of architecture. Daniel Bosia of Arup’s Advanced Geometry Unit in London recommended us to him. It turns out our studio is about six blocks from Matthew’s in New York. That’s how the collaboration between the three of us came about.

W*: What were the challenges of working with an artist?

BA: There seems to always be an expectation of friction between an artist and architect and that somehow that friction becomes the source of energy in a project. It was a little different with us, early on we all agreed on an integrated approach, where every single one of Ritchie’s lines would be structural. It was a simple strategy: the piece is a drawing in three dimensions where the lines themselves are the structure and the space. The challenge was to develop a system to carry this out so it worked not just for one line, but the thousands of lines that exist in the project.

W*: Can you tell us something about the Design Miami space you are designing?

BA: It is the new home for Design Miami/ in Miami’s Design District and is by far the largest edifice we’ve ever built. We’re using a standard tent-system in a not so standard way to create very generous spaces for exhibiting furniture and design objects. As important to the inside is its urban presence in the Design District, so we’ve created a highly customized facade that allows people to interact with the building in unexpected ways and also makes for a strong urban move.

W*: As architects, do you see yourselves presenting your own works in a gallery setting at some point in the future?

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

BA: Yes, even recently we’ve had the fortune of showing our work at the MoMA and we are represented by The Johnson Trading Gallery in New York. But to answer more generally: it’s a vital part of our practice. I would extend this “gallery setting” you mention to also include institutional support in the art and architecture world. This support has fostered our practice from the beginning. We learned how to be the architects we are today from projects that involved pigeon-flyers in Brooklyn, basket weavers in Arizona, and a big billboard in Queens. We received public grants for each of these, which are now hallmark projects for us. It is not possible to do this speculation through the familiar career paths offered to architects today. Our method is ad-hoc and opportunistic; it is about generating the support needed for a series of varied speculative projects that are self-directed, research intensive and experimental. They also seem outside of professional practice but this is only initially true. As we have begun to receive recognition from these speculative projects, we have entered a new phase where opportunities to build have emerged. We believe now more than ever that the creation of a unique and independent voice is the only way to see ideas built.

W*: Do you think the art/architecture theme was present at this year’s biennale?

If so, do you think it is a new and prominent trend?

BA: I hope so. Our own experience working with artists has been profoundly rewarding and continues to recast our ideas about architecture. It reminds us that neither discipline is too fixed to not change.

W*: What does the idea of Beyond in architecture mean to you?

BA: I think it’s about the relations that exist around a building. We once made some baskets with a Native American basket weaver Terrol Johnson. He taught us that there exists a certain disengagement from the object being formed and weaving becomes more about the relations around that object. He spoke of basket making as a process that brings people together, both those around him and the ancestors through which he continues a tradition. He spoke of many voices in that object, as if each basket is, in essence, a conversation. I think Beyond Architecture has to do with this conversation between universal themes around a simple object and the actual experience of people, communities and cities through which it becomes manifest.

W*: What are you currently working on?

BA: Because our recent interest is in crystallographic structures, we tend to jump scales in our projects. Currently we are applying our designs at the scale of the molecule, furniture, installation and building. And then some New York lofts for good measure.

W*: What are you future plans?

BA: We haven’t come up for air in a long time; it’s been one thing to the next, each one more challenging than the last. So after some rest, maybe a road trip through Mexico, we’re just going to keep doing what we’re doing.

ENDS/

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

The Bombardier Global 8000 flies faster and higher to make the most of your time in the air

The Bombardier Global 8000 flies faster and higher to make the most of your time in the airA wellness machine with wings: Bombardier’s new Global 8000 isn’t quite a spa in the sky, but the Canadian manufacturer reckons its flagship business jet will give your health a boost

-

A former fisherman’s cottage in Brittany is transformed by a new timber extension

A former fisherman’s cottage in Brittany is transformed by a new timber extensionParis-based architects A-platz have woven new elements into the stone fabric of this traditional Breton cottage

-

New York's members-only boom shows no sign of stopping – and it's about to get even more niche

New York's members-only boom shows no sign of stopping – and it's about to get even more nicheFrom bathing clubs to listening bars, gatekeeping is back in a big way. Here's what's driving the wave of exclusivity

-

Out of office: coffee and creative small talk with Tatiana Bilbao

Out of office: coffee and creative small talk with Tatiana BilbaoBodil Blain, Wallpaper* columnist and founder of Cru Kafé, shares coffee and creative small talk with leading figures from the worlds of art, architecture, design, and fashion. This week, it’s Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao, who is currently designing a brutalist, ethical aquarium in Mazatlán and has an exhibition at Copenhagen's Louisiana Museum of Modern Art opening in October 2019

-

At home with Deborah Berke

At home with Deborah BerkeArchitect Deborah Berke talks to us about art, collaboration, climate change and the future, from the living room of her Long Island home

-

Rheaply redefines circular economy in architecture

Rheaply redefines circular economy in architectureOn Earth Day 2022, we speak to Rheaply founder Garry Cooper Jr about his innovative business that tackles reuse and upcycling in architecture and construction

-

Paolo Soleri's sustainable urban experiment Arcosanti enters new era

Paolo Soleri's sustainable urban experiment Arcosanti enters new eraWe meet Liz Martin-Malikian, Arcosanti’s new CEO, who takes us through the vision and future for Paolo Soleri's sustainable urban experiment

-

International Women’s Day: leading female architects in their own words

International Women’s Day: leading female architects in their own wordsInternational Women’s Day 2022 and Women’s History Month: Wallpaper* talks to four leading female architects about dreams, heroines and navigating the architecture world

-

Sou Fujimoto judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Sou Fujimoto judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022We chat with Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022 judge Sou Fujimoto about his work in Japan and abroad, and our shortlisted designs and winners

-

Dream the Combine cross-pollinates and conquers

Dream the Combine cross-pollinates and conquersThe American Midwest is shaking up the world of architecture. As part of our Next Generation 2022 project, we’re exploring ten local emerging practices pioneering change. Here we meet Minneapolis duo Dream the Combine

-

Architecture in the words of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Architecture in the words of Paulo Mendes da RochaGreat modernist Paulo Mendes da Rocha passed away on 23 May 2021 aged 92. Here, we revisit the interview he gave Wallpaper* in 2010 for our Brazil-focussed June issue, talking about architecture, awards and his home country