Enter the world of Cave Bureau, and its architectural and geological explorations

Nairobi practice Cave Bureau explores architecture’s role in the geological afterlives of colonialism, as part of a team exhibiting at the British pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

Cave Bureau is a Nairobi-based group of architects and researchers whose work examines the post-colonial African condition through the lens of landscape. Central to their exploration is a strong anthropological and geological thread that both underscores the origin and informs the future trajectory of the practice.

The studio, founded in 2014, owes its name to its geographic origins in Kenya. More specifically, Cave Bureau’s proximity to a site known as the Cradle of Humankind in South Africa spawned an interest in the origin of the human race as a species. The site in question - a series of subterranean limestone caves that proved instrumental in informing human evolutionary theories – continues to be a rich metaphor for a body of work that is grounded in place and topography. This historical narrative is balanced by studio co-founder Kabage Karanja’s childhood experience of inhabiting some of the caves native to his hometown of Nairobi. ‘I have memories, from the age of 12 or 13, of sleeping in caves. Incidentally, [the cave] has become the main site of our research - for all of our Anthropocene projects, culminating with Anthropocene 10 - it has come full circle,’ he says.

Meet Kenyan architecture studio Cave Bureau

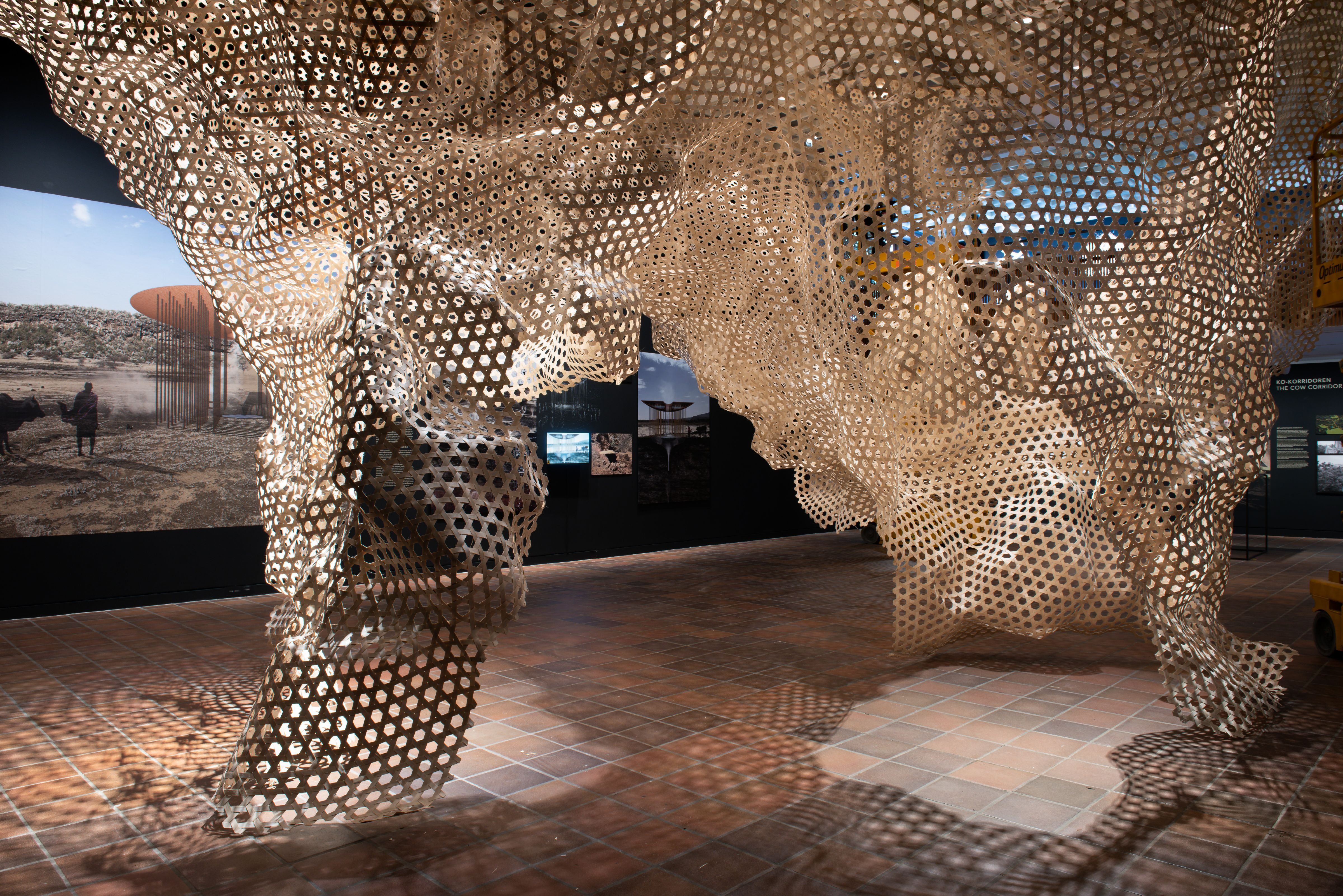

One of Cave Bureau’s early projects, completed for the 17th Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2021, exemplifies this root origin. Invited to contribute a piece within the Giardini Galileo Chini, the studio created Obsidian Rain, a 1:1 installation of the Mau Mau Freedom Fighters’ hideout caves. The aim was to recreate the visceral topographic interior of the space by hanging 1,680 pieces of obsidian stone. This, alongside myriad other projects, contributes to a growing catalogue of work referred to as The Anthropocene Museum - which they explain on their website as ‘a living, roaming institution of imagination and community-based action that began in the land of our collective ancestral origin in East Africa’.

In recent years, The Anthropocene Museum has become central to Cave Bureau’s ambition to interrogate the prevailing modern concept of the museum as an institution contained within a building. In Africa, the storage and transmission of cultural knowledge was historically an oral tradition. Often rooted in nature, it integrated other experiential elements, such as poetry and dance, making for an embodied form of learning. ‘The traditional museum, as an institution where objects are stored to be looked at and engaged with, is a Western, post-Enlightenment concept we are trying to re-imagine. With the Anthropocene Museum, its use of a range of sensory media, as well as physically roaming around the world with several iterations in differing western museums, acts as a critique,’ explains Cave Bureau’s co-founder Stella Mutegi.

During the 2020 global pandemic, the practice noticed a marked deficiency in cultural provision due to the closing down of many larger institutions. With outdoor green spaces being the only public places people were allowed to visit at the time, this observation further strengthened their investigations into landscapes as natural harbingers of culture.

World Map Extract: Cave Bureau’s Counter Imperial Federation Map of the world

Importantly, the studio’s research underlines that site and geography are not only used as points of historical reference but constitute springboards from which projections about alternative futures can be envisaged. Much like the Mau Mau Freedom Fighters who re-imagined a better, future African State while hiding during the resistance, Cave Bureau’s work uses the specificity of place as a point of departure from which a future in dialogue with the past can be proposed. The centrality of geology and land as a contested space is vital towards this end. ‘A lot of what is happening today – conflict, climate and natural disasters – can be traced back to geology and human engagement with land, effectively back to the earth. Climatic changes go back to extraction from the earth, as do conflicts between people as a result of resource grabbing,’ explains Mutegi. ‘There is extraction of not only natural but also human resources.’

The common ground for these intersections highlights geology as a point of focus – a theme that Cave Bureau hopes to explore through its work at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025. Titled Geology of Britannic Repair, the British pavilion will investigate how architecture can reverse the destructive impacts of colonial systems of geological extraction through emergent practices of architectural repair. Commissioned by the British Council, and led by an expert multidisciplinary team including UK-based curator and writer Owen Hopkins and academic professor Kathryn Yusoff, the curatorial team cites The Great Rift Valley – a geological formation that runs from southern Turkey through Palestine, the Red Sea to Ethiopia, Kenya and Mozambique – as the basis for the exhibition’s geographical, geological and conceptual focus.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

With an underlying partnership between Britain and Kenya the focus of this year’s British Pavilion, the curatorial team hopes to prompt reflection on architecture’s role in the geological afterlives of colonialism, as well as propose ideas of healing and repair through a showcase of earth practice that rebuilds connections between people, ecology and land.

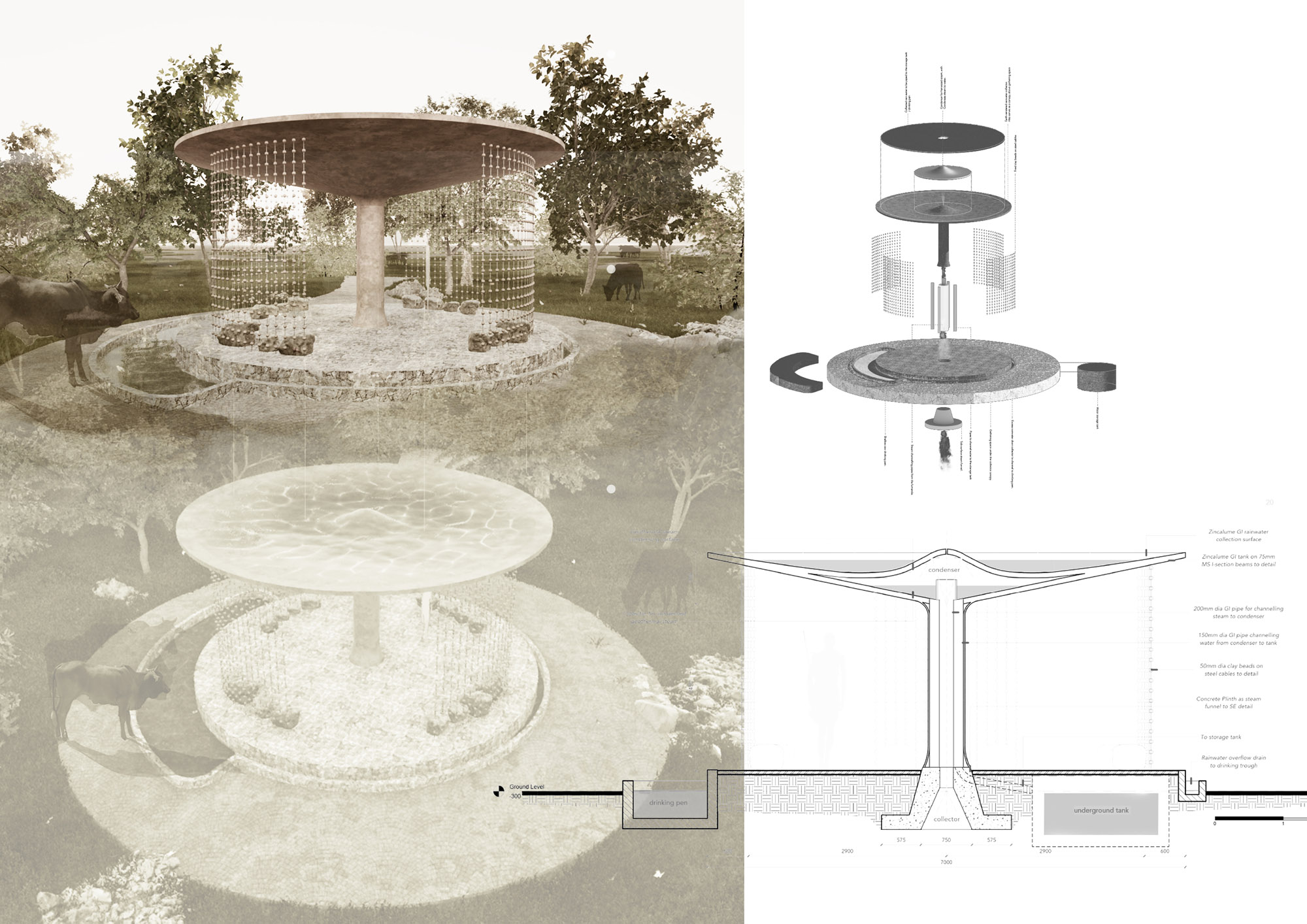

For Cave Bureau, this has always been part of any decolonial exploration. Projects such as the Rift Valley in Mount Suswa – a site of traditional importance to the Indigenous Masai who relied on its increasingly depleting resources – explore extraction on a smaller scale, showcasing how communities harvest water here, while also prompting us to think holistically about existing ecosystems of plant and animal life. ‘For us, earth practices start with community but if expanded can have a planetary impact - this is the argument – a geologic consciousness. It is the small-scale practices that are vulnerable. If we protect the small scale, we have a chance to dismantle the big scale,’ says Mutegi.

The British Pavilion building itself is no exception. Describing its origin as ’the manifestation of empire', and with the 'entire Giardini complex an expression of European excellence, there is a desire to unravel this history and how the colonial project has led to immense climatic impacts,’ Karanja says. The building, no longer a vessel or backdrop for hosting work as has been the case in previous exhibitions, will be subverted to become the subject of a greater conversation around the physical and geological manifestations of colonial activity, drawing the attention of visitors to what has been in the background for so long.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architect

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architectPioneering Lisbeth Sachs is the Swiss architect behind the inspiration for creative collective Annexe’s reimagining of the Swiss pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

By Adam Štěch

-

‘Ranger’: documenting ‘the first female conservation ranger programme in East Africa’

‘Ranger’: documenting ‘the first female conservation ranger programme in East Africa’‘Ranger’, a new film set in Kenya’s Maasai homeland, tells the story of 12 women who became East Africa’s first all-female anti-poaching unit

By Mary Cleary

-

Venice Architecture Biennale 2025: the ultimate guide

Venice Architecture Biennale 2025: the ultimate guideThe time for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 launch is nearing and our ultimate guide for the what, who and where of the biannual festival is here to help you navigate the Italian island city and its rich exhibition offerings

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Year in review: top 10 architecture stories of 2023, selected by Wallpaper* architecture editor Ellie Stathaki

Year in review: top 10 architecture stories of 2023, selected by Wallpaper* architecture editor Ellie StathakiStathaki presents her top 10 architecture stories of 2023, from a world-leading festival to lesser-known 20th-century architecture, contemporary transport hubs, museums and a pool to splash in

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Carlo Ratti announced curator of Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

Carlo Ratti announced curator of Venice Architecture Biennale 2025Carlo Ratti has been revealed as the Director of the Architecture Department at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025, with the specific task of curating the 19th International Architecture Exhibition

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Year in review: the top 10 house stories of 2023, as selected by Wallpaper’s Ellie Stathaki

Year in review: the top 10 house stories of 2023, as selected by Wallpaper’s Ellie StathakiDiscover our top 10 house stories of 2023, from modernist reinventions to urban dwellings and idyllic retreats

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Falcon House is a Kenyan retreat rooted in simplicity and a site-specific approach

Falcon House is a Kenyan retreat rooted in simplicity and a site-specific approachFalcon House by PAT was designed as a private home that feels at one with its natural surroundings in Kenya’s Manda Island

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Nexus House caters to the Los Angeles lifestyle near Venice Beach

Nexus House caters to the Los Angeles lifestyle near Venice BeachNexus House by Woods + Dangaran is a Venice house perfect for the Los Angeles lifestyle

By Ellie Stathaki