Traditional South Korean architecture meets innovation in a renovated hanok house

What hutongs are to China, hanoks are to Korea. These clusters of traditional low-rise family houses have evolved over centuries, tailor-made to the cultural and climatic needs of their particular territory. In recent decades, though, they have been rapidly disappearing to make way for modern developments.

Among Seoul’s urban mix of scales and styles, few hanoks remain intact after the city experienced – like many of its Asian counterparts – a century of wars and rapid urbanisation. As a result, a historic wooden hanok house is an extremely rare property to own, and the old, upscale neighbourhood of Bukchon is one of the few examples of hanok clusters still around.

Savvy locals know that when the opportunity comes up to buy a hanok – or land within a hanok cluster – it’s a once-in-a-lifetime project. So when Seoul-based designer Teo Yang was approached by a client with a plan to rebuild a hanok in Bukchon as a modern home, he understood the importance of working with such precious architectural heritage.

An Artek pendant lamp and chairs in the dining room, where a ‘moon’ window offers a view of Downtown Seoul.

‘Even though Korea has lost much of its heritage over time, the studio’s goal is to find innovation and space based on our tradition,’ he says. ‘And hanoks are a key source of inspiration, where we can bridge present and past, especially in a country where forward-thinking and cutting-edge development is celebrated. I believe preservation and further study of hanok houses are crucial to keep our original local spirit alive.’

The project involved reconstructing a hanok that once sat on the site but was demolished in the early 2000s. The client, a businessman, property developer and keen art collector, spotted the plot in Bukchon and jumped at the opportunity. His aim was to use the land to build his own contemporary home, while maintaining the old structure’s footprint and traditional Joseon dynasty style. ‘The client wanted to enjoy the tradition, but made it clear that he did not want to live in an 18th-century house,’ says Yang.

A desk area in the basement lounge.

‘We had to create a space where tradition and present coexist. So we generated a very distinctive design for the two different floors, creating a traditional atmosphere for the upper floor, and a more Western, modern atmosphere for the lounge downstairs.’

The central courtyard is one of the most prominent areas of the house. As is traditional, the space is an extension of the ground floor, blending indoors and out. Here, Yang gave history a modern twist, steering clear of the customary heavily decorated courtyard doors and opting for clean, floor-to-ceiling glass openings, highlighting the visual connections between the interior and the outdoors.

RELATED STORY

This transparency brings in natural light, and also encourages self-reflection, says Yang. ‘Confucius believes that the house is a reflection of its owner. By looking at one’s house, one gets the chance to think about one’s own behaviour and by having full-height transparent glass windows, the house allows its dweller to look at it from all angles.’

A reading room was added off the courtyard, as a nod to the historical ‘men’s quarter’, a part of the house where Joseon dynasty nobility would retire to study, write poetry and relax. The remaining rooms surrounding the courtyard on the ground floor include a study, a master bedroom, an open-plan kitchen and dining area, a bathroom, a living room and the entrance foyer. The basement contains a media lounge, a wine cellar, a walk-in wardrobe and a garage.

Expert artisans were employed to carry out the house’s intricate woodworking – and everything, from treating and drying the timber to the final, meticulous sizecutting and joinery work, was done by hand.

The main entrance hall

The architect also favoured more traditional finishes and detailing where possible, such as using handmade black and patterned tiles when constructing the garden walls, leatherwork for the door handles, and flower motif-decorated doors, all produced by specialist carpenters.

The owner’s personal art collection, ranging from historical Korean earthenware dating from 5AD to a painting by Julian Opie, is carefully framed in various parts of the house. The crown jewel, a series of abstract Dansaekhwa paintings from the 1970s, is located on the lower level, where celebrated minimalist Korean artist Lee Ufan’s painting From Line also hangs.

Offering a balanced blend of Korean history and modern comforts, this hanok’s rebirth is a rare treat – and part of a growing trend among Seoul’s culture-savvy crowd. Yet, simply owning a hanok is not enough to truly bring this architectural legacy back to life, cautions Yang. ‘It is important to know and study the originality of the hanok and respect its roots before renovation starts,’ he says. An approach he has followed to the letter in his Bukchon masterpiece.

As originally featured in the October 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*235)

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The reading room, where a munijado screen adorned with calligraphy based on Confucius’ noble values stands behind a pair of Finn Juhl ‘Reading’ chairs

The main living room, with artworks by Teo Yang, Kibong Rhee and Julian Opie, and furniture by Teo Yang and Pierre Jeanneret

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Teo Yang Studio website

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Join our tour of Taikaka House, a slice of New Zealand in Seoul

Join our tour of Taikaka House, a slice of New Zealand in SeoulTaikaka House, meaning ‘heart-wood’ in Māori, is a fin-clad, art-filled sanctuary, designed by Nicholas Burns

By SuhYoung Yun

-

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practices

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practicesIn the Wallpaper* Architects Directory 2024, our latest guide to exciting, emerging practices from around the world, 20 young studios show off their projects and passion

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Studio Heech transforms a Seoul home, nodding to Pierre Chareau’s Maison De Verre

Studio Heech transforms a Seoul home, nodding to Pierre Chareau’s Maison De VerreYoung South Korean practice Studio Heech joins the Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024, our annual round-up of exciting emerging architecture studios

By Tianna Williams

-

Remembering Alexandros Tombazis (1939-2024), and the Metabolist architecture of this 1970s eco-pioneer

Remembering Alexandros Tombazis (1939-2024), and the Metabolist architecture of this 1970s eco-pioneerBack in September 2010 (W*138), we explored the legacy and history of Greek architect Alexandros Tombazis, who this month celebrates his 80th birthday.

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Sun-drenched Los Angeles houses: modernism to minimalism

Sun-drenched Los Angeles houses: modernism to minimalismFrom modernist residences to riveting renovations and new-build contemporary homes, we tour some of the finest Los Angeles houses under the Californian sun

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Architect Byoung Cho on nature, imperfection and interconnectedness

Architect Byoung Cho on nature, imperfection and interconnectednessSouth Korean architect Byoung Cho’s characterful projects celebrate the quirks of nature and the interconnectedness of all things

By Ellie Stathaki

-

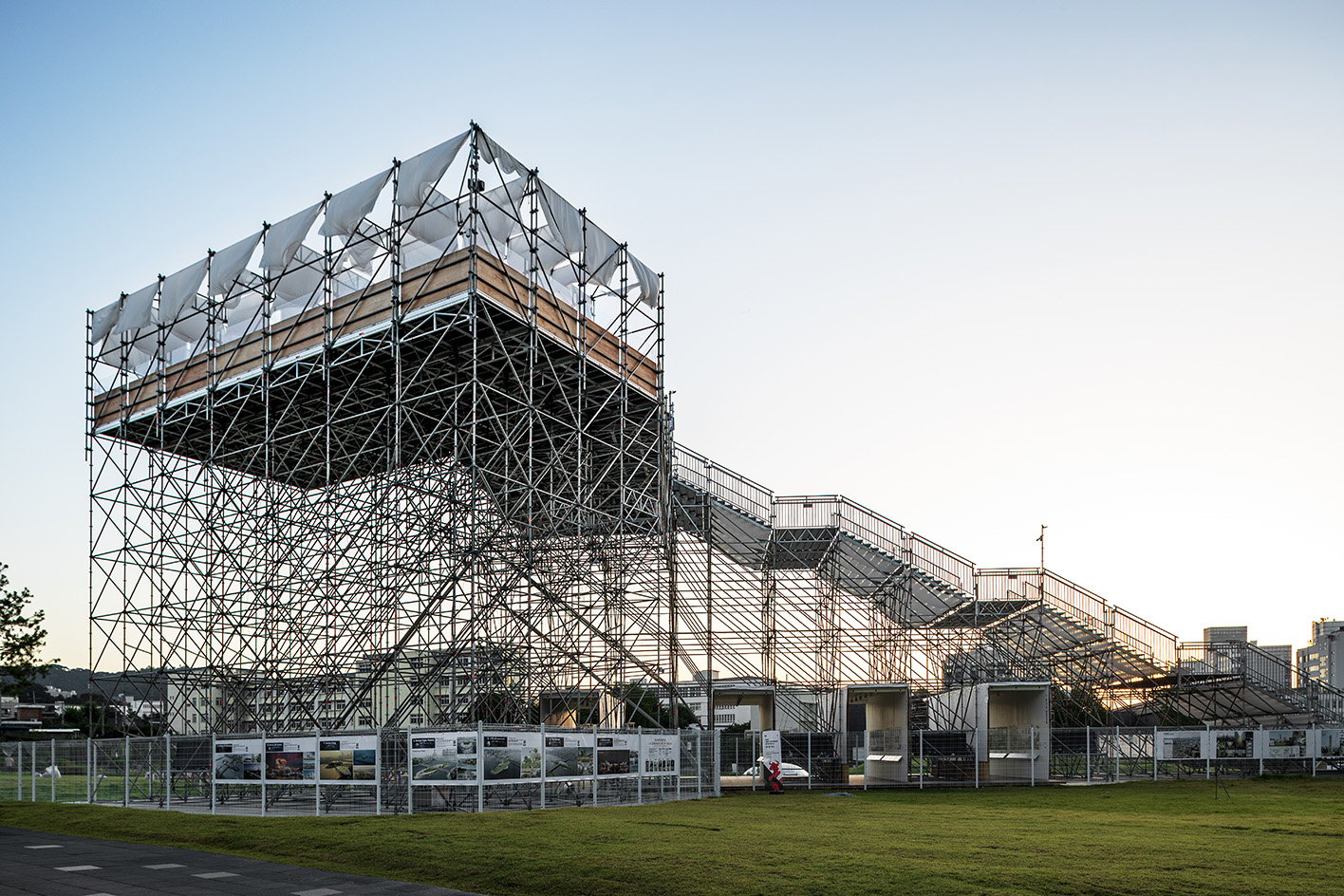

2023 Seoul Biennale of architecture invites visitors to step into the outdoors

2023 Seoul Biennale of architecture invites visitors to step into the outdoorsSeoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2023 has launched in the South Korean capital, running themes around nature and land through the lens of urbanism

By SuhYoung Yun

-

Tadao Ando’s ‘Space of Light’, a meditation pavilion, opens in South Korea

Tadao Ando’s ‘Space of Light’, a meditation pavilion, opens in South KoreaTadao Ando’s ‘Space of Light’ pavilion opens at Museum SAN in South Korea

By SuhYoung Yun