Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Jean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

One highlight of 2025’s European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF) fair in New York (9-13 May) will be a jewel of post-war French architectural history: two yellow steel frames, resembling massive upside-down tuning forks, each standing 3m tall. They were fabricated in 1947-1948 as part of the Croismare Professional Training School for Glassmakers, the largest demountable structure ever built by French designer and self-taught architect Jean Prouvé. Design dealer Patrick Seguin, who has championed Prouvé’s legacy since the late 1980s (with projects in recent years including the showcasing of Prouvé's House of Better Days in Paris in 2024, and the installation of demountable house at Château La Coste in 2019) and owns the world’s biggest collection of his architecture, is featuring Croismare along with nine other Prouvé buildings at the fair.

After the Second World War, France needed to rebuild, and quickly. Prouvé, who trained as a metal craftsman, had developed an ingenious system for making small, demountable buildings with load-bearing portal frames, for purposes ranging from military barracks to refugee housing. The nomadic quality of his buildings also reflected his embrace of environmentalism, seeking to make what he called ‘architecture that leaves no trace on the landscape’.

Discover Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure

One of Prouvé’s friends was master glassmaker Paul Daum, a member of the French resistance who died in a concentration camp in 1944. Prouvé and the Glassmakers’ Union honoured Daum’s wish to ensure the industry’s future by building a training centre for young apprentices. Despite Croismare’s impressive size (8m x 32m plus awnings), Seguin says, ‘There is no difference between the construction principles of Prouvé’s 6 x 6 house and this monumental building.’ The former could be assembled by three people in a day, while Croismare took six men one week to construct, armed with little more than a screwdriver and ladder.

Croismare contains all the fundamentals of Prouvé architecture. Its interior is traversed by a succession of portal frames, six yellow and one green, marking the separation between classroom and refectory (an adjoining dormitory now belongs to a collector). Jointed central beams connect the portals along the length of the ceiling, while floor-to-ceiling glazed doors offer light and expansive views of the landscape.

Jean Prouvé’s school for glassmaking apprentices was built in 1948 in Croismare, in north-east France, and closed in 1953

In 1953, Croismare was closed, and the building was abandoned until the 1990s, when Seguin and his partner, Philippe Jousse, acquired it. After the two dealers parted ways in 2000, Jousse kept Croismare. He started restorations, including replacing a stone section with wood panels identical to the others, and removing the dropped ceiling to expose the remarkable skeleton of Prouvé’s work. Seguin bought Croismare from Jousse four years ago and continued its meticulous restoration, from retouching the paint on the portal frames to replacing the poured concrete base with a portable system of Ductal concrete blocks (first developed by Jean Nouvel for another Prouvé structure).

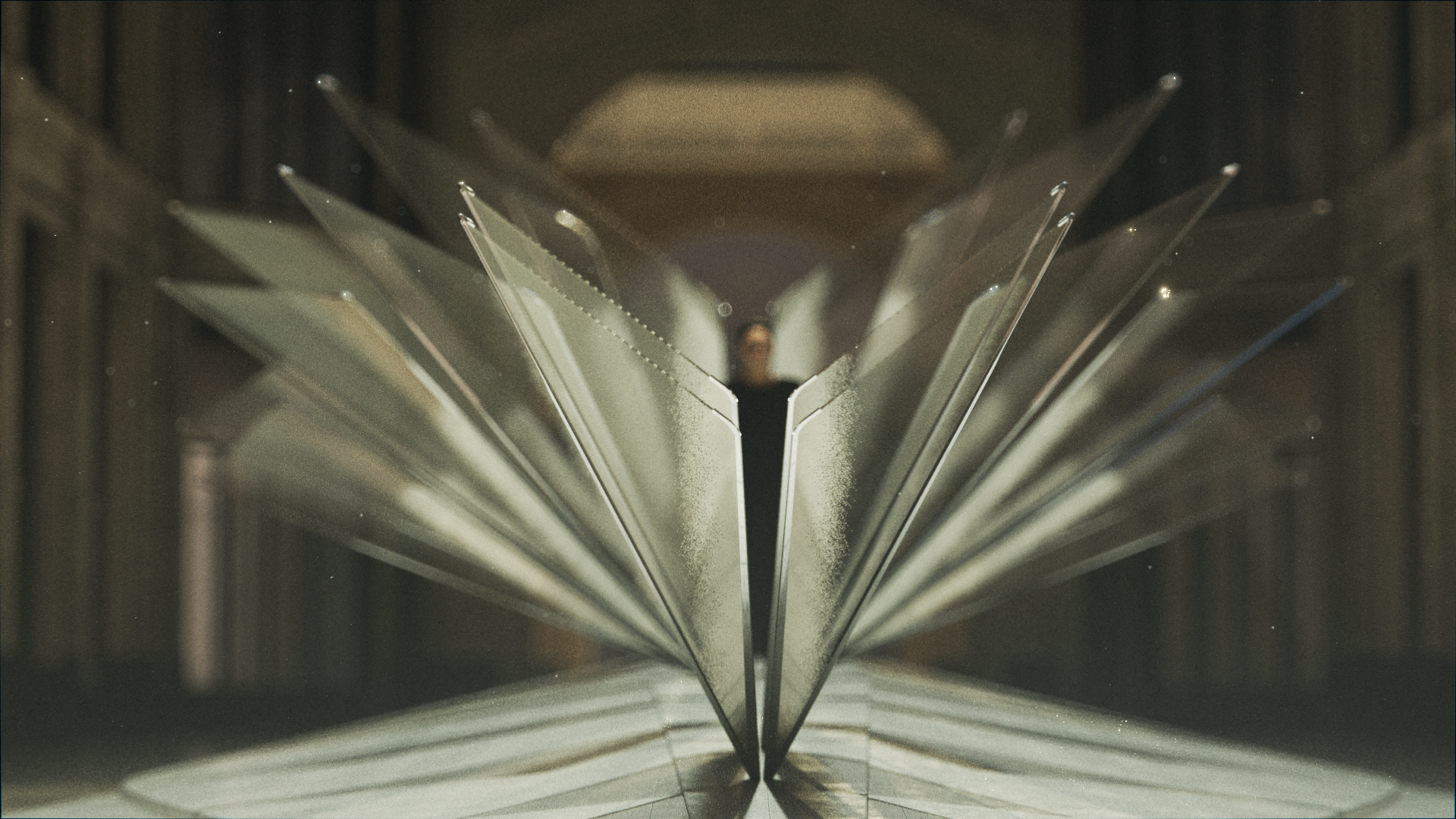

The Croismare school photographed at Laurence and Patrick Seguin’s estate in the south of France

Seguin recalls Pritzker Prize laureate Richard Rogers once saying, ‘If we taught architecture at high school, Prouvé would be the best person to do it’, since his methods were so elegant and simple to understand. Prouvé made no distinction between constructing furniture or buildings: form equalled function. Seguin holds up an archival photo of a 1953 building for which Prouvé built a metal awning, comparing it to a photo of his ‘Compas’ table. ‘All that’s missing is the chairs.’

It’s impossible to guess who might buy Croismare; in the past, Prouvé’s buildings have been snapped up by collectors from Azzedine Alaïa to Richard Prince. A new book by Seguin’s gallery, Jean Prouvé: From Furniture to Architecture, The Laurence and Patrick Seguin Collection, offers a look at how the couple live with Prouvé’s works. It contains photos of their apartment in Paris, where midcentury chairs and tables exist happily alongside artworks by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Wade Guyton, and their home in the south of France, where Prouvé houses are scattered around the property, as modern as ever.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

TEFAF New York is on show from 9-13 May at the Park Avenue Armory

Video credit: Jean Prouvé, Croismare school, 1948 © Galerie Patrick Seguin (2025), Réalisation Le visiomatique

This article appears in the May 2025 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands from 3 April, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

-

Esperit Roca is a restaurant of delicious brutalism and six-course desserts

Esperit Roca is a restaurant of delicious brutalism and six-course dessertsIn Girona, the Roca brothers dish up daring, sensory cuisine amid a 19th-century fortress reimagined by Andreu Carulla Studio

By Agnish Ray Published

-

Bentley’s new home collections bring the ‘potency’ of its cars to Milan Design Week

Bentley’s new home collections bring the ‘potency’ of its cars to Milan Design WeekNew furniture, accessories and picnic pieces from Bentley Home take cues from the bold lines and smooth curves of Bentley Motors

By Anna Solomon Published

-

Asus chose Milan Design Week as the springboard for its new high-end Zenbooks

Asus chose Milan Design Week as the springboard for its new high-end ZenbooksMilan Design Week 2025 saw Asus collaborate with Studio INI to shape an installation honouring the slimline new Zenbook Ceraluminum Signature Edition laptop series

By Craig McLean Published

-

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, UzbekistanThe legacy of modernist architecture in Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent, is explored through research, a new publication, and the country's upcoming pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; here, we take a tour of its riches

By Will Jennings Published

-

The Frick Collection's expansion by Selldorf Architects is both surgical and delicate

The Frick Collection's expansion by Selldorf Architects is both surgical and delicateThe New York cultural institution gets a $220 million glow-up

By Stephanie Murg Published

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

What is hedonistic sustainability? BIG's take on fun-injected sustainable architecture arrives in New York

What is hedonistic sustainability? BIG's take on fun-injected sustainable architecture arrives in New YorkA new project in New York proves that the 'seemingly contradictory' ideas of sustainable development and the pursuit of pleasure can, and indeed should, co-exist

By Emily Wright Published

-

How Le Corbusier defined modernism

How Le Corbusier defined modernismLe Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

The Eagan house from 'Severance' is available to rent

The Eagan house from 'Severance' is available to rentThe Taghkanic House by Thomas Phifer serves as the home of Lumon’s CEO in the AppleTV+ series, and can be rented out for dystopian stays

By Anna Solomon Published

-

How to protect our modernist legacy

How to protect our modernist legacyWe explore the legacy of modernism as a series of midcentury gems thrive, keeping the vision alive and adapting to the future

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st Century

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st CenturyThanks to a sensitive redesign by Studio Hagen Hall, this midcentury gem in Hampstead is now a sustainable powerhouse.

By Ellie Stathaki Published