David Chipperfield opens up infinite possibilities with his extension for London’s Royal Academy of Arts

I remember standing in the dark outside 6 Burlington Gardens, escaping the hubbub of ‘Sensation’ at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA), five minutes’ walk and a world away. Peering out gloomily into the greyness of late 1997, the building – home to the Museum of Mankind for almost three decades – was now shuttered up. It was a squarish slab of neoclassical architecture in the high style. It had once been white. It was sparely ornamented with statuary dedicated to British cultural heroes and a few ‘illustrious foreigners’ accorded (almost) equal status. Its columns and porticoes were beautiful, but burly, Victorian approximations of Hellenic originals, coarsened once by Roman tastes before finally being given a dose of Anglo-Saxon heft.

Creatively, as an ethnographic offshoot of the British Museum, the Museum of Mankind certainly had its moments. As a destination space, it had been a dead loss. It was a dead block in a deadening part of town. Savile Row had never spilled round the corner and the Albany, the apartment complex next door that had been home to Basevi and Byron, kept its own counsel. This was a building no one quite knew what to do with.

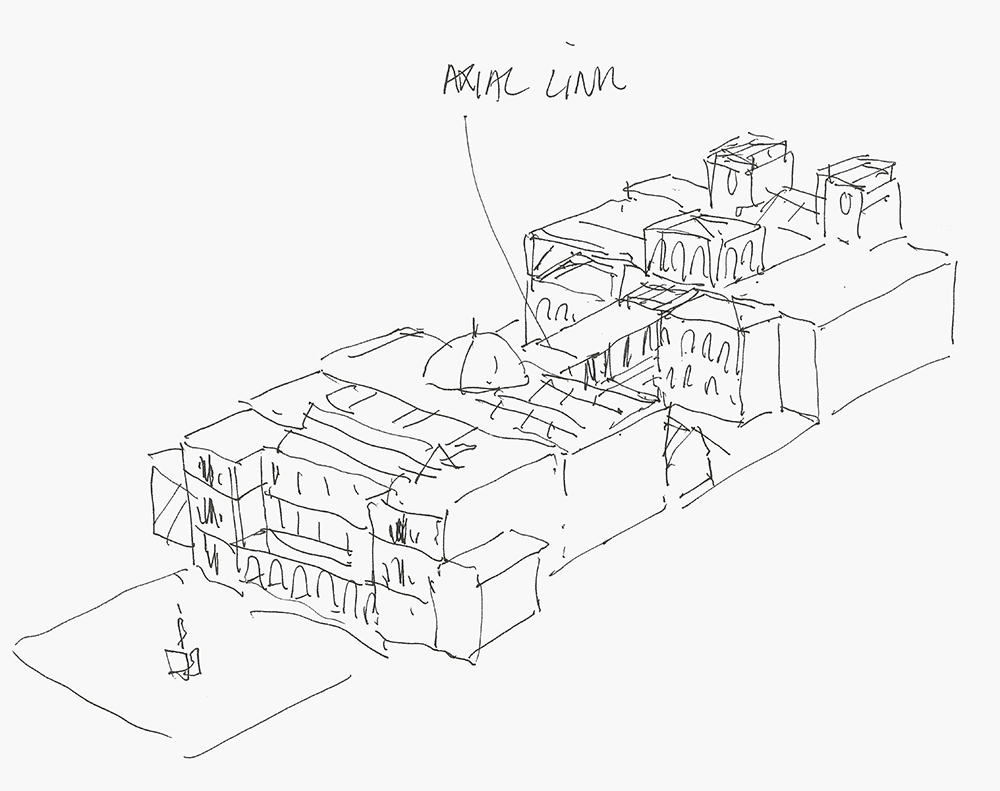

An early concept drawing by Chipperfield shows the new bridge that links the Royal Academy’s original Burlington House building and the new Burlington Gardens annex.

Or so it seemed. A tortuous two decades of planning disagreements and false starts later, astonishing new gallery spaces, a 250-seat double-height lecture theatre that updates Epidaurus for the digital age, and for the first time a splendid, adventurous physical connection to the main RA building on Piccadilly will help create a whole new cultural hub in the heart of the capital, courtesy of the most in-demand art-world architect.

Burlington Gardens has all the signature elements of David Chipperfield’s topology, which is to say, the complete absence of signature. It’s what has made him, along perhaps with Renzo Piano, the pre-eminent shaper of cultural spaces today. After years of ebullient art space architecture – often much hated by the artists themselves – there was demand for more rigour, honesty and restraint. Chipperfield offers that in spades.

The Wohl Entrance Hall at the Royal Academy of Arts.

‘He is so good at context,’ agrees RA artistic director Tim Marlow. ‘He doesn’t have a signature style but can work interestingly in so many different styles. So when you think about the Neues Museum in Berlin, the Hepworth Wakefield, Turner Contemporary or his museum for literature in Germany, you see he’s got such breadth but there is a real rigour to him as well. More than anything, he understands artists; I think he would be very interesting to talk to about ways of engaging with the space on a programming level.’

Chipperfield himself characterises projects such as Burlington Gardens or the Neues Museum as ‘interventions’ and is happy to downplay their import. No one, he says, will leave Burlington Gardens talking about a David Chipperfield project, and that is exactly as it should be. ‘I don’t think architecture should be waving all the time,’ he says. ‘I mean there are some times when it needs to be waving more than others. If you are in an industrial site in the middle of Wakefield and you’ve got to help rejuvenate a city that has been beaten to bits, then you have to start waving your hands a little more than you might do if you’re in the middle of Berlin or London. But generally I think the time for icons has passed. People are now rather suspicious; they ask why is this building so expensive. Museums had become confused with branding.’

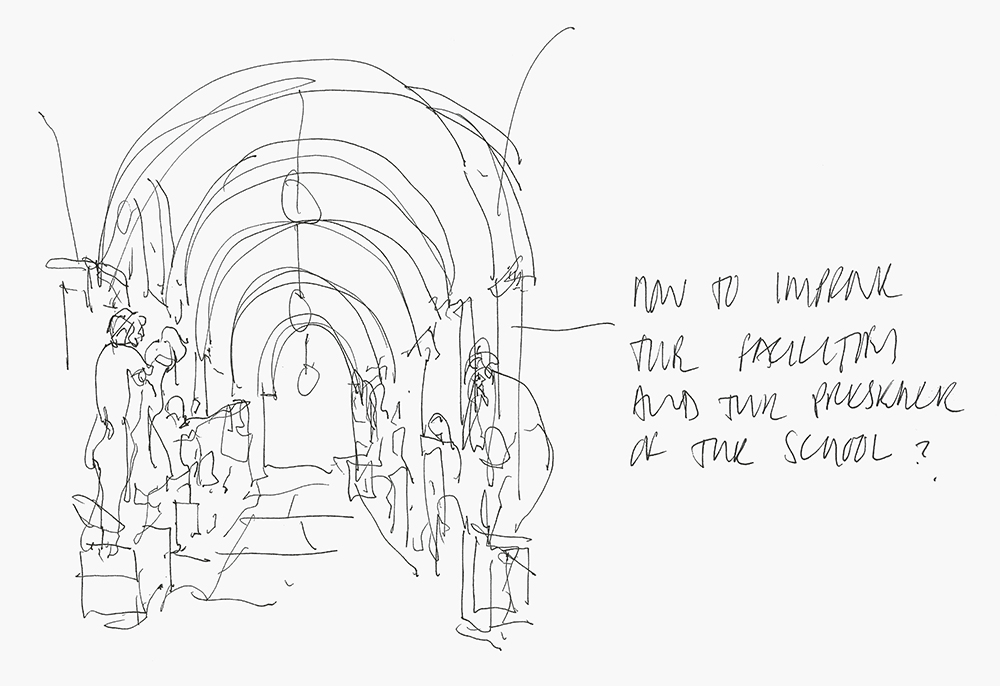

Early concept drawing of the RA Schools’ cast corridor.

All the same, his beautiful work at Burlington Gardens is, if anything, even more radical than at the Neues Museum. The interior certainly offered a less promising palette than Berlin. It was a dull misto of years and styles: all corridor and hallway, not nearly as large as the façade made it appear. It had served successively as space for the University of London, the HQ of an ill-fated National Antarctic Expedition, and Civil Service offices, all before its stint as the Museum of Mankind. Since 1997, parts of the building have hosted temporary exhibitions for the RA, and galleries such as Haunch of Venison and Pace. But in all the principal rooms the years had left their mark – partition walls, Formica desks, false ceilings and grubby greige paint. There were modifications and mezzanines. An institutional memory lingered. Much of the circulation around the building had happened through fire doors and up cramped service wells, brightly lit by bare 100W bulbs, like a Martin Parr Polaroid.

This was what the RA acquired in 2001. In theory, it had added a large listed Italianate building 30m to the rear of the Royal Academy Schools complex, with which it could connect to expand its footprint. In practice, it was much less straightforward.

‘We wanted to bring the grandeur back,’ says RA president Christopher Le Brun. ‘But as the years passed without real progress, the discussions intensified with people wanting to knock it down and keep only the façade.’ Le Brun, a Royal Academician since 1996, actually started working on the project before the RA had raised the funds to buy it. The original master plan, by Michael Hopkins, had involved an ambitious scheme to glaze over the space between the two buildings, British Museum-style. The costs exploded, and the plans were shelved. A second, more modest, plan by Sandy Wilson was then adopted. But the RA Schools, located between 6 Burlington Gardens and the RA’s main site at Burlington House, wouldn’t let a link go through their space, and there was nowhere else on site to relocate a 50 or so-strong student body. ‘So Sandy’s plan made the link go all the way around the outside,’ explains Le Brun. ‘This wasn’t popular. I remember a meeting where we showed it to all the architects in the RA. As of one person they said no; they hated it. I think Piers Gough even used a rude word. They said it’s obvious, you have to go straight through the middle to connect the spaces.’

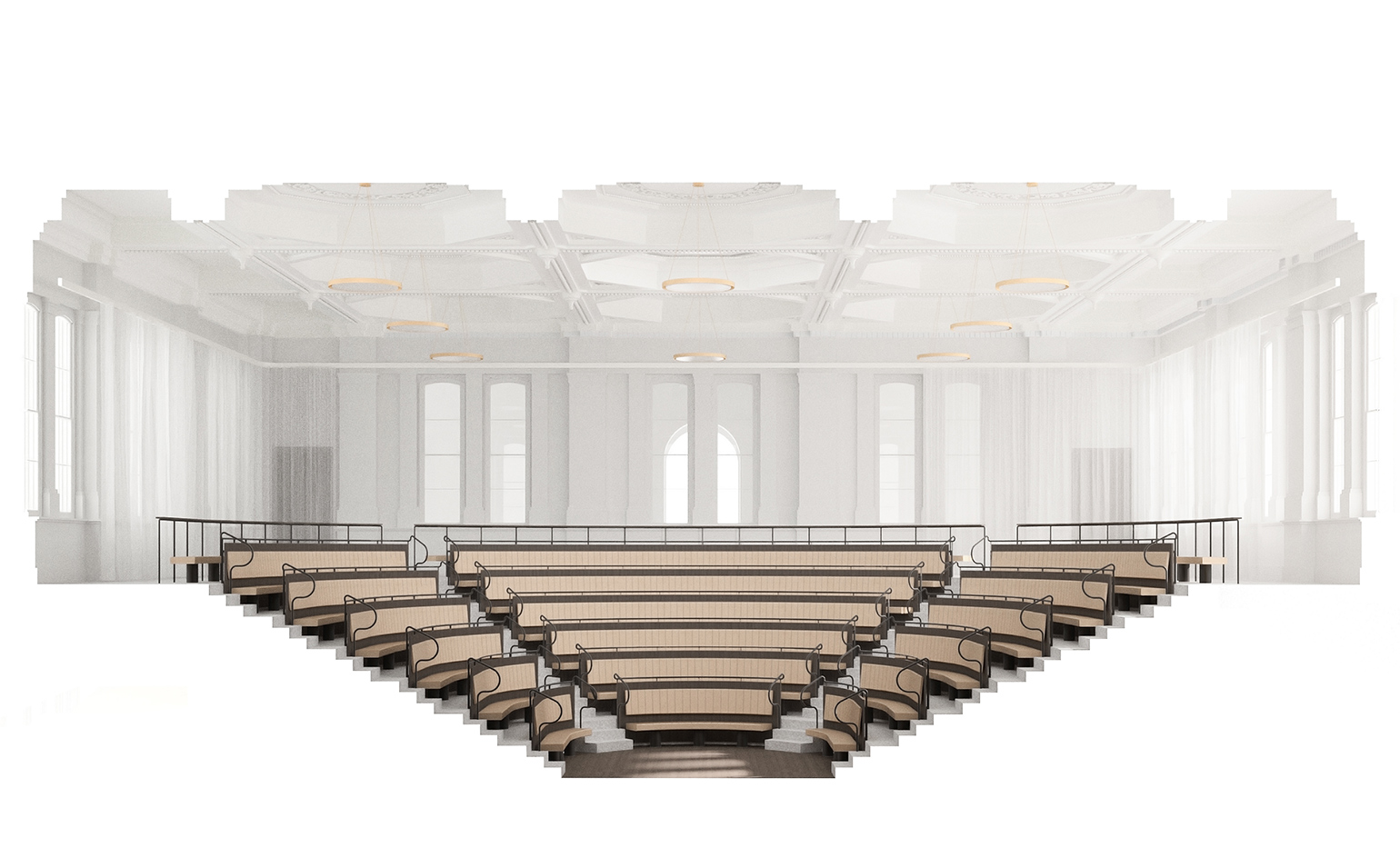

The Benjamin West lecture theatre.

The project stalled again; the second master plan lapsed on Wilson’s death in 2007. It seemed for a while that a grand project might never happen – until a third competition was held. ‘David Chipperfield won it, with a scheme that did indeed go through the middle of the site, and everything changed,’ says Le Brun. ‘I went to talk to the schools with David’s project architect, and they saw the quality of his scheme and quickly agreed to it. That made all the difference. And as soon as we could go through the middle of the site, all of David’s ideas – a light touch, being straightforward, respecting the integrity of the original building: they all worked. We could start to see it really was a beautiful building underneath. He had just done the Neues Museum. He was clearly ideal. Not only was he an Academician, he was able to treat a historic building with tact and sympathy but also fairly robustly, not over-respectfully.’

Now, finally, this plan is coming to life, just in time to mark the RA’s 250th anniversary. Like the Neues, much of the pleasure is in the detailing. Chipperfield’s favourite space is a former brick vault he reclaimed from acres of piping, which now serves as an exhibition space. Lit by pendant lamps designed by the architect, the grand circulation spaces lead to impressive new display areas. Tacita Dean will open the space, and then a major Renzo Piano show will bring architecture to the new building, something that is envisaged as an essential part of the new programming. A permanent architectural studio will host a programme of year-long interventions, and for the first time there will be a full event and lecture programme. ‘Having this amazing lecture room is key,’ says Marlow. ‘There is so much discussion and debate at the RA. Now we have the space to programme as much as we want.’

Early concept drawing of the Burlington Gardens’ façade.

All told, the plan increases the RA’s gallery space by 70 per cent. Chipperfield has also retained the windows in a new middle gallery that overlooks the centre of the site, and created a huge gallery in the west, where the RA will show some of its permanent collection – much of which is currently in storage – for the first time.

But the absolute key, the proposal which unlocked the whole site, is the link bridge. Bar the lecture theatre, it’s the only bit of what Le Brun calls ‘freestanding Chipperfieldness’, and it’s spectacular. From it you look out into the hidden courtyard and the schools at the heart of the RA. And because the collections galleries are free, they will surely help the RA become a destination between its hugely influential shows.

‘My feeling about architecture,’ says Chipperfield, ‘is that visitors don’t have to look at everything all the time. They have to be happy in the ambience of the place, and only then do they realise someone has put a lot of time into the detailing of it. Detailing has no purpose on its own. Design has no purpose on its own. But I do think that someone can smell or feel when trouble and care has been taken. That was our experience of Neues, and that is what we are hoping for here.’

As originally featured in the June 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*231)

Weston Bridge and The Lovelace Courtyard.

The Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries.

The Vaults.

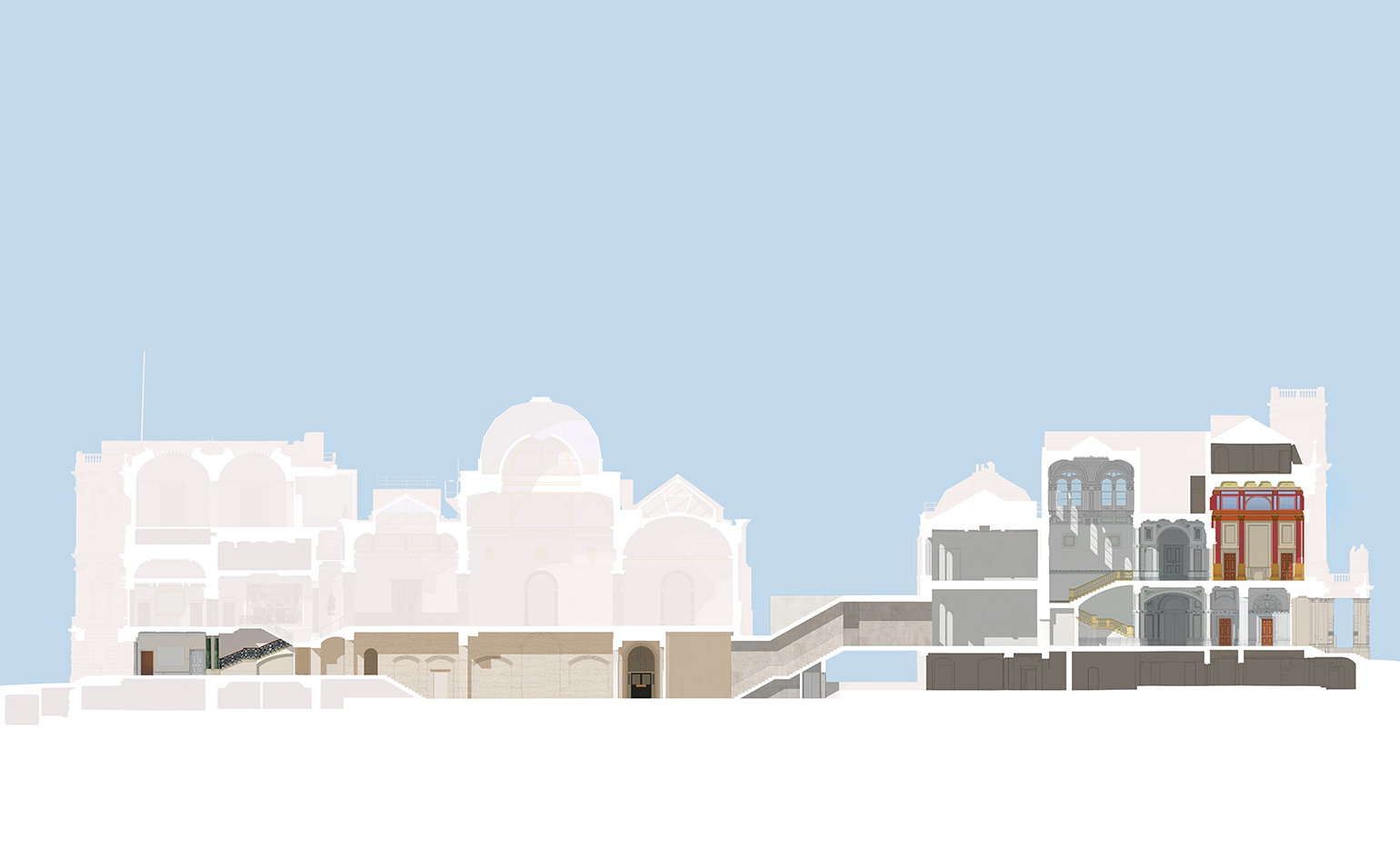

Cross-section view of the Royal Academy.

Section view of lecture theatre.

INFORMATION

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The new Royal Academy of Arts opens on 19 May. For more information, visit the Royal Academy of Arts website and the David Chipperfield website

ADDRESS

Royal Academy of Arts

Burlington House

Piccadilly

Mayfair

London W1J 0BD

-

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibition

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibitionWallpaper’s highlights from the mega-exhibition at Rossana Orlandi Gallery include some of the most compelling names in design today

By Anna Solomon

-

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewellery

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewelleryNikos Koulis experiments with unusual diamond cuts and modern materials in a new collection, ‘Wish’

By Hannah Silver

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Meet the 2024 Royal Academy Dorfman Prize winner: Livyj Bereh from Ukraine

Meet the 2024 Royal Academy Dorfman Prize winner: Livyj Bereh from UkraineThe 2024 Royal Academy Dorfman Prize winner has been crowned: congratulations to architecture collective Livyj Bereh from Ukraine, praised for its rebuilding efforts during the ongoing war in the country

By Ellie Stathaki

-

RA’s 2024 Summer Exhibition celebrates making and multidisciplinarity in architecture

RA’s 2024 Summer Exhibition celebrates making and multidisciplinarity in architectureAt the Royal Academy’s 2024 Summer Exhibition, London collective Assemble brings together works from across the creative fields into the architectural rooms (18 June – 18 August 2024)

By Herbert Wright

-

The Royal Academy Schools' refresh celebrates clarity at the London institution

The Royal Academy Schools' refresh celebrates clarity at the London institutionThe refreshed home for the Royal Academy Schools by David Chipperfield Architects together with Julian Harrap Architects is revealed in London

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Space Un celebrates contemporary African art, community and connection in Japan

Space Un celebrates contemporary African art, community and connection in JapanSpace Un, a new art venue by Edna Dumas, dedicated to contemporary African art, opens in Tokyo, Japan

By Nana Ama Owusu-Ansah

-

Stephen Friedman Gallery by David Kohn is infused with subtly playful elegance

Stephen Friedman Gallery by David Kohn is infused with subtly playful eleganceStephen Friedman Gallery gets a new home by David Kohn in London, filled with elegant details and colourful accents

By Ellie Stathaki

-

The Architecture Window opens in London offering space for ‘micro-exhibitions’

The Architecture Window opens in London offering space for ‘micro-exhibitions’The Architecture Window by Unknown Works opens at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, creating space for creative exploration and fresh voices around the built environment

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Royal Academy Dorfman Award 2023 winner is Taller Gabriela Carrillo

Royal Academy Dorfman Award 2023 winner is Taller Gabriela CarrilloThe Royal Academy Dorfman Award 2023 has been announced, revealing Taller Gabriela Carrillo as its winner at a dedicated event in London this evening

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Royal Academy’s Herzog & de Meuron show in London spotlights architecture for care

Royal Academy’s Herzog & de Meuron show in London spotlights architecture for careThe Royal Academy of Arts launches its Herzog & de Meuron exhibition in London; we speak to them about the show, their approach to healthcare architecture and caring, and their rich body of work

By Amah-Rose Mcknight Abrams