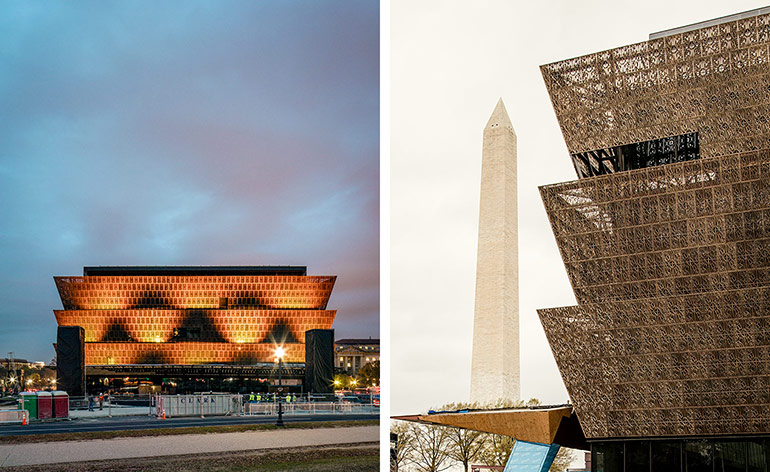

Design Awards 2016: Best Cultural Draw – National Museum of African-American History and Culture

With its exterior walls now in place and glinting above the National Mall – the green swathe at the heart of Washington, DC – the National Museum of African-American History and Culture (NMAAHC), our Design Awards 2016 Best Cultural Draw, is most of the way through its four-year build. But the vision it fulfills is much older than that.

In 1915, black veterans of the US Civil War proposed building a national memorial to African-American achievement. The idea languished for decades, and attempts to revive it in the 1970s and 80s met with political opposition. Finally, in 2003, the US Congress authorised a museum dedicated to the African-American experience, and assigned it the last buildable site on the Mall, close to the Washington Monument.

A competition in 2009 narrowed the museum’s possible designers down to just one: the Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup, consisting of The Freelon Group, Adjaye Associates, Davis Brody Bond and SmithGroup.

The challenge facing lead designer David Adjaye was daunting. Dreamed up by Washington’s original planner, Pierre L’Enfant, and enshrined under the 1901 McMillan Plan, the Mall is a hallowed landscape for Americans, replete with iconic structures, including the US Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial. ‘How do you add to one of the most important master plans in the world?’ asks Adjaye.

He proposed a stately ziggurat clad in a decorative facade, its tiered floors inspired by the crowns that top columns in the Yoruban architecture of West Africa. The museum’s architects call this form the ‘corona’, and they angled these tiers at precisely 17 degrees to match the Washington Monument pinnacle.

Last summer, workers installed the 3,600 panels of the corona. Made of aluminium coated in a bronze-coloured finish, they pay homage to the decorative ironwork made by enslaved artisans in 19th-century New Orleans and Charleston. The filigree patterns are ‘a computer-generated, modern interpretation’, says Philip Freelon, the museum’s architect of record. The design team chose a range of opacities varying from 65 to 90 per cent. ‘The skin [is] not monolithic in the way it’s perforated,’ Freelon says. ‘It varies, which gives the building its complexity.’ From the outside, the appearance of the wrapper changes depending on the weather and time of day.

The skin will also help to control heat gain on the south, the direction from which most visitors will arrive. This side of the 400,000 sq ft museum features a deep canopy inspired by vernacular African-American architecture. In front of the porch, a reflecting pool will relieve the heat of DC’s muggy summers.

Once inside, visitors will proceed to the galleries above and below – a full 60 per cent of the interior space lies underground. There will be sections devoted to history, culture and community (including sports and military history). From the outset, the designers had to strike a careful balance. They wanted to represent the injustice of slavery and discrimination, but also to celebrate black achievement.

When it opens this autumn, NMAAHC will convey both ‘uplift and recognition of despair’, according to Lonnie Bunch, director of the museum. On the concourse level, visitors can look up and see five storeys rising into the sky. ‘That notion of resiliency, of belief in a better day, is captured in that,’ Bunch says. Other spaces will be more difficult to experience. A darkened triangular room will display artifacts from a slave ship and project the stories of people involved in the slave trade. To allow for quiet reflection, the architects put an oculus-like fountain with seating at the north end.

Bunch also says one of his priorities for the new building was that it be of the Mall and not just on it. Often, ‘you walk into buildings on the Mall and you’re in the building – you forget you’re on the Mall’, he says. The team strove to establish a strong connection to the landscape. Through carefully chosen openings, visitors can look out at the graves of black war heroes in nearby Arlington Cemetery, or, discomfitingly, at the former site of a slave pen on the Mall’s grounds.

For Adjaye, the moments of both pride and unease reinforce a larger point, that ‘the migration of a group of people changed a nation’. The museum ‘stands with and against the other institutions on the Mall’, he says, echoing Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes, ‘with exactly this purpose: to say that this, too, is American history; this, too, is America.’

As originally featured in the February 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*203)

See the Design Awards 2016 in full – including our extra-special Judges' Awards - here

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the NMAAHC’s website

Photography: Stefan Ruiz

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Eddie Olin's furniture that merges heavy metal with a side of playfulness

Eddie Olin's furniture that merges heavy metal with a side of playfulnessWallpaper* Future Icons: London-based designer and fabricator Eddie Olin's work celebrates the aesthetic value of engineering processes

-

This retreat deep in the woods of Canada takes visitors on a playful journey

This retreat deep in the woods of Canada takes visitors on a playful journey91.0 Bridge House, a new retreat by Omer Arbel, is designed like a path through the forest, suspended between ferns and tree canopy in the Gulf Island archipelago

-

Terrified to get inked? This inviting Brooklyn tattoo parlour is for people who are 'a little bit nervous'

Terrified to get inked? This inviting Brooklyn tattoo parlour is for people who are 'a little bit nervous'With minty-green walls and an option to 'call mom', Tiny Zaps' Williamsburg location was designed to tame jitters

-

Eckhaus Latta explores consumption, desire and surveillance in solo New York exhibition

Eckhaus Latta explores consumption, desire and surveillance in solo New York exhibition -

Diller Scofidio + Renfro on the divine design of the MET’s ‘Heavenly Bodies’ exhibition

Diller Scofidio + Renfro on the divine design of the MET’s ‘Heavenly Bodies’ exhibition -

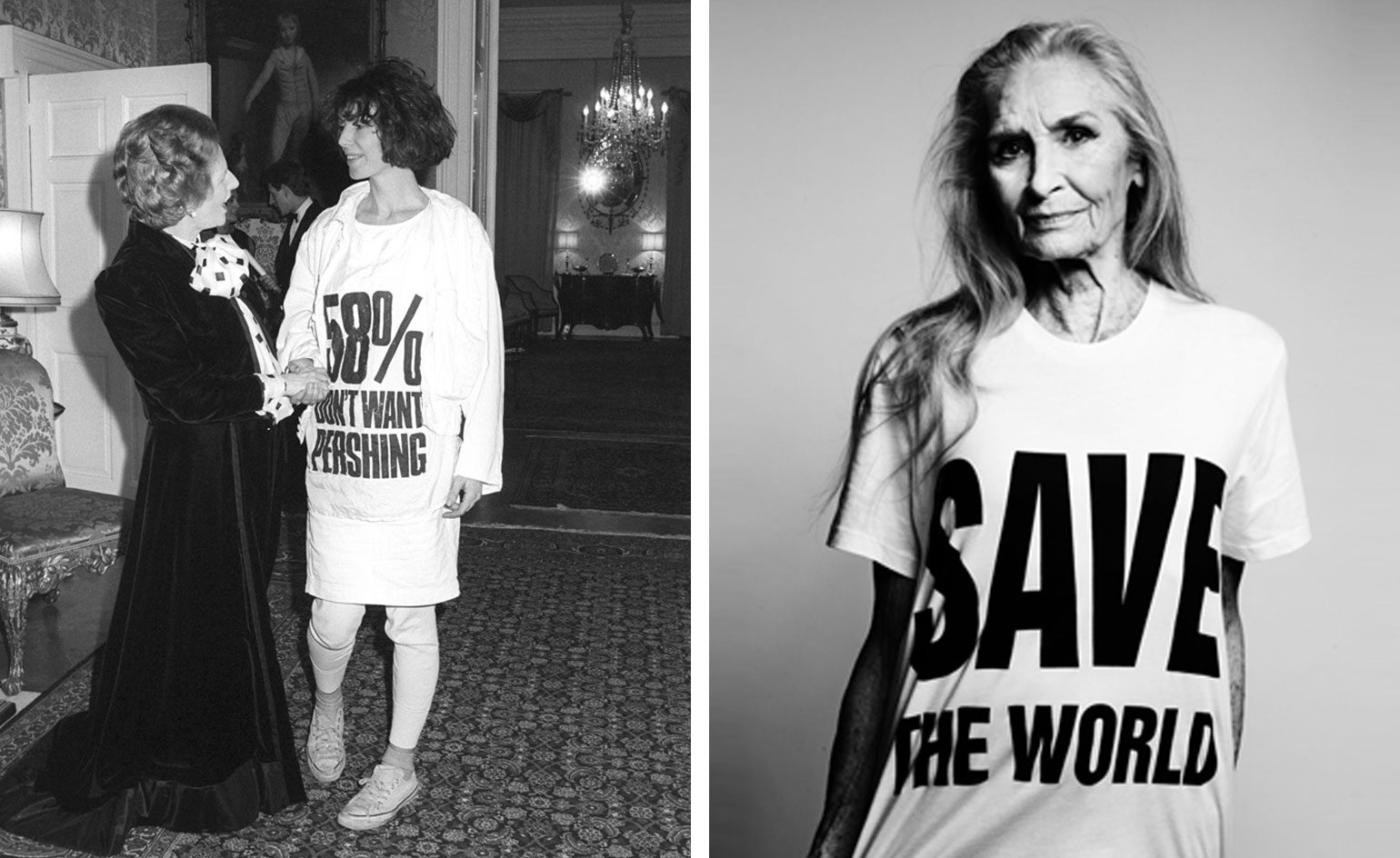

T-shirt power: the London exhibition exploring the subversive sway of the slogan tee

T-shirt power: the London exhibition exploring the subversive sway of the slogan tee -

Face off: Walter Van Beirendonck explores the marvel of masks

Face off: Walter Van Beirendonck explores the marvel of masks -

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo lays bare the house’s artistic inspirations

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo lays bare the house’s artistic inspirations -

’So Far, So Goude’: Jean Paul Goude retrospective arrives in Milan

’So Far, So Goude’: Jean Paul Goude retrospective arrives in Milan -

Flora blossoms a new exhibition at Florence’s Gucci Museo

Flora blossoms a new exhibition at Florence’s Gucci Museo -

Creative luminaries imagine the uniforms of the future in a new Milan exhibition

Creative luminaries imagine the uniforms of the future in a new Milan exhibition