The 10 emerging West African architects changing the world

We found the most exciting emerging West African architects and spatial designers; here are the top ten studios from the region revolutionising the spatial design field

From Senegal to Nigeria, and from Niger to the Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa is vast and brimming with potential. A powerful mix of peoples and cultures, and in some nations, exponential demographic and economic growth, makes this part of the world a locus of change. The result? A dynamic new generation of studios that operate in the architecture realm and push the boundaries of their field towards a promising future. Architects, spatial designers and builders converge here to create a unique, rich melting pot of fresh thinking and innovation that will no doubt reshape the way we think about architecture globally.

The ten emerging West African architects and spatial design studios to know

Limbo Accra, Ghana

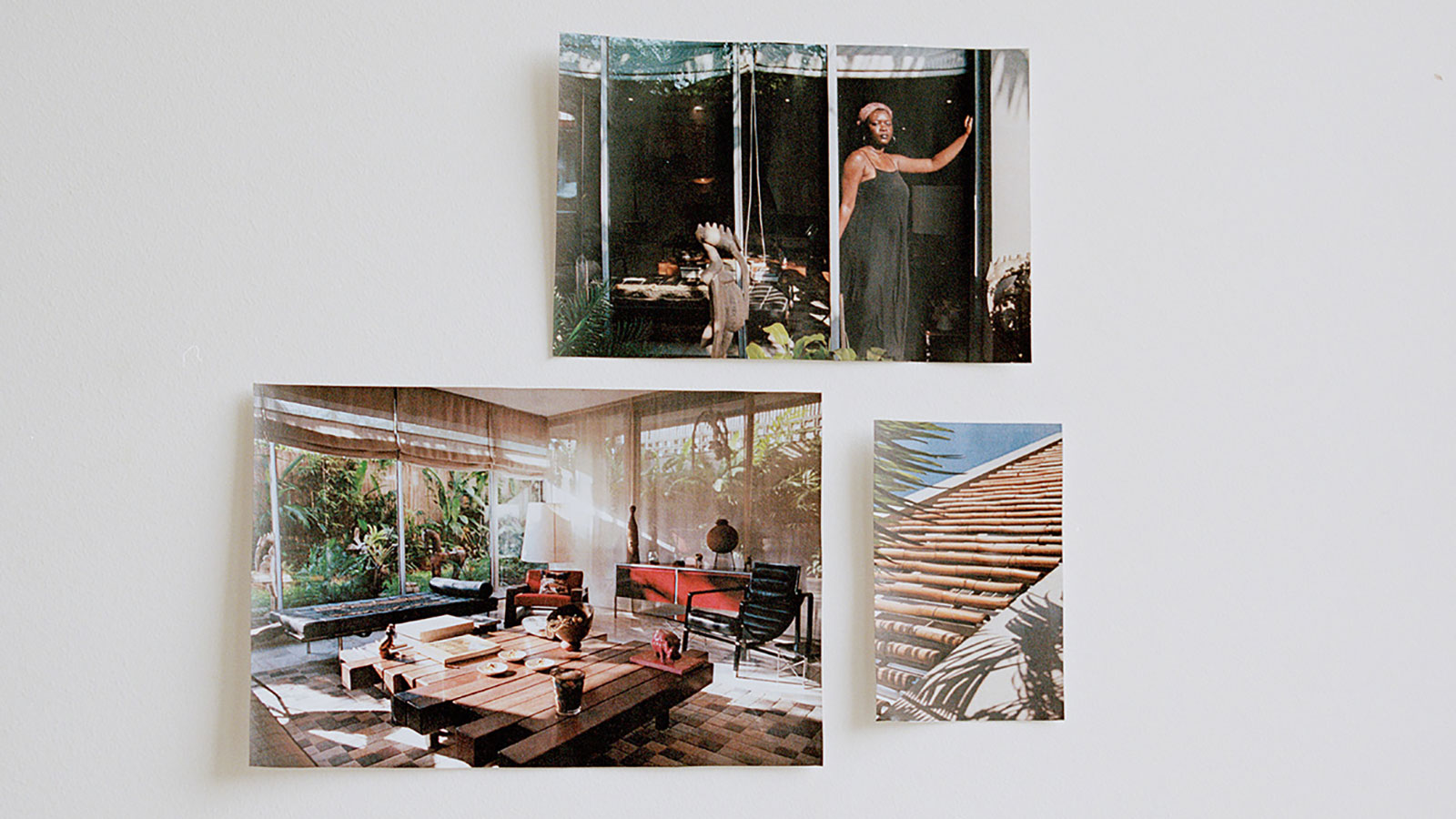

More of a spatial design studio than an architecture firm, Limbo Accra is a practice that defies categorisation. Set up in Accra, Ghana, in 2018 by Dominique Petit-Frère and Emil Grip, its name was inspired by the large number of uncompleted buildings scattered throughout the city. ‘These structures await a future while fossilised with fragments of the past,’ explain the founders. ‘Since they were never completed, we can only ask: what is their purpose altogether then?’

While Petit-Frère and Grip are not registered architects (they have backgrounds in education and international relations), they work with designers and architects and have a strong spatial understanding of the world. Their output spans continents, all composed through collaborations with architects in Accra, Copenhagen, London, Abidjan, Bombay and beyond.

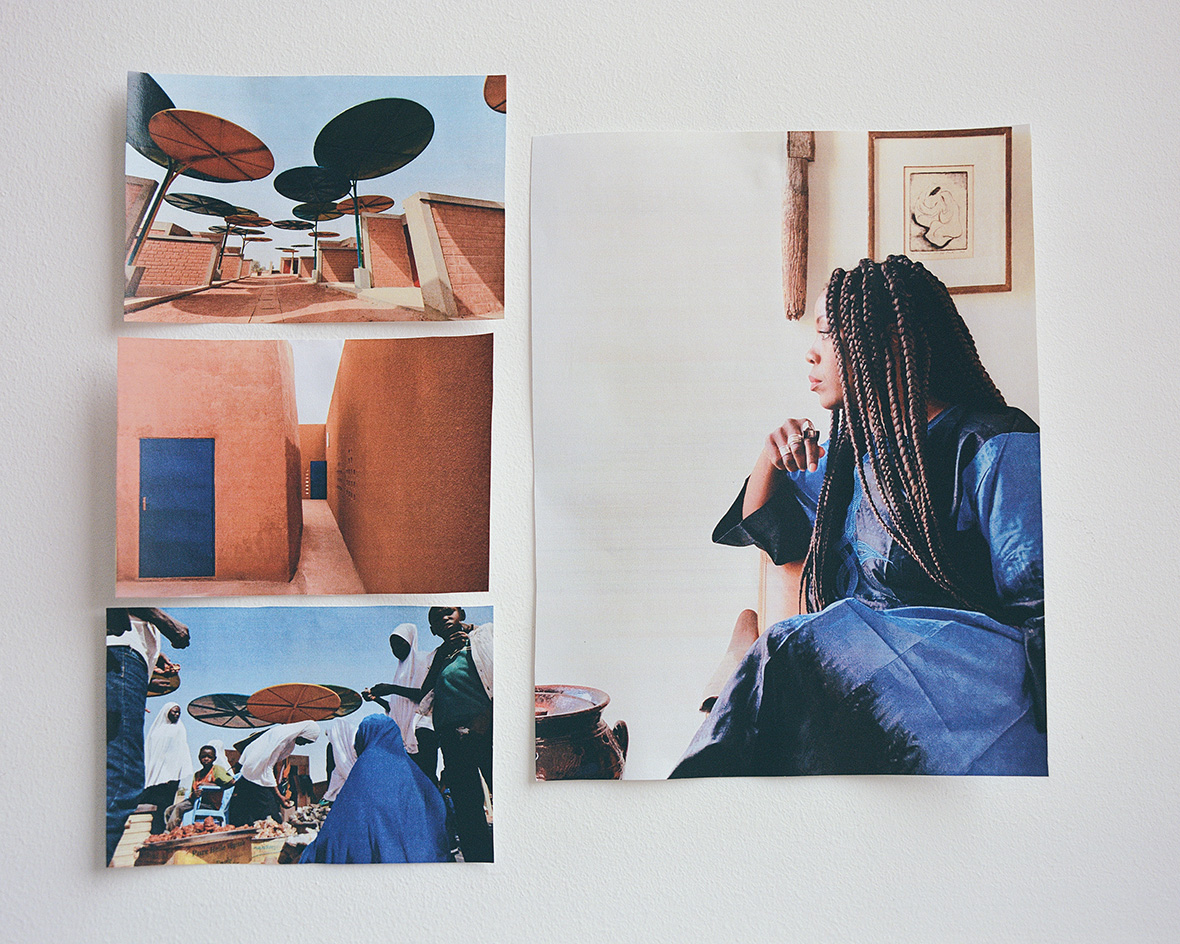

Atelier Masōmī, Niger

Mariam Issoufou Kamara’s practice, Atelier Masōmī, was founded in 2014. Now 16-strong, the firm balances work between its main office in Niger’s capital city, Niamey, and a studio in New York. ‘I work on ways of creating new interpretations for wisdoms that can be found in traditional buildings,’ says Kamara. ‘At the core of our approach is the belief that as architects we have an important role to play in creating spaces that have the power to elevate, dignify and provide a better quality of life. The goal is always to design spaces that bring communities together while also honouring the cultural history, context and the people we are designing for.’

The studio’s current projects are spread across Niger (where it is finishing the Yantala Offices building); Senegal (the Bët-bi Museum is currently in design development); Sharjah (with the Hayyan master plan and housing development); and Liberia (where the team is working with Sumayya Vally on the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center and Library). The studio’s public commissions celebrate context-specific approaches: ‘The canon has an incredible tunnel vision elevating works from one small part of the world as universal, which really only narrows the field of references available to us,’ says Kamara. ‘When we’re tackling global issues, would it not make sense for our arsenal of tools and ideas to also be global in scope?’

Studio Contra, Nigeria

A mutual desire to create innovative architecture for African cities motivated Olayinka Dosekun-Adjei and Jeffrey Adjei to establish their joint practice, Studio Contra, in 2016. Having met while working for the British architecture firm Sheppard Robson, Dosekun-Adjei, who was raised in Nigeria, and Adjei, a Ghanaian, decided to set up their own studio in Lagos. Drawn to its energy and commercial dynamism, they saw the city as the perfect platform to effect social change and express cultural ideas through design.

Today, the 15-strong practice is working on a spate of cultural commissions in Kwara, a state in western Nigeria. These include the Ilorin Museum and Garden, where a colonialera museum is to be redeveloped into a café and gift shop, and a new 35,000 sq ft space will be built to house classical Nigerian sculptures. Also in the works is a 24,000 sq ft Institute of Contemporary African Art & Film in Kwara; and the transformation of a disused sugar factory into film studios.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jeannette Studio, Côte d’Ivoire

Mélissa Kacoutié, who founded Jeannette Studio in 2016, hopes to bring poetry into the Ivorian architectural milieu. To her, architecture is a multifaceted vessel for artistic expression, as apparent in one of the studio’s early and defining projects, Le Bazar. A festival venue designed for Abidjan’s Bain de Foule Studio in 2019, the lightweight structure was built using wooden pallets. Like all of Kacoutié’s projects, it has a strong distinguishable element; in this case, an eye-catching, bright pink façade.

Each of her builds is a ‘liveable artistic installation’, while still slotting seamlessly into the landscape. ‘Architecture should be experienced like an animation,’ she says, emphasising the merit in embracing one’s environment, in order to reach that hard-topinpoint poetic potential. It can mean using unpredictable local materials, such as woven palms – a technique which she employed to create a façade for her project Pavilion Bassam, though she wove metal sheets together instead of palm for added durability.

Mamy Tall, Senegal

‘I have always been passionate about architecture,’ says Mamy Tall. ‘I am dedicated to informing people about the importance of planning and maintaining cities, raising awareness on bioclimatic construction and the debate about heritage and its place in our societies, creating bridges between fashion and architecture, and understanding our political system and its impact on our trade.’

Tall grew up in Togo and trained as an architect in Canada before making Senegal her home. The dynamic designer enjoys multitasking and this becomes immediately clear when she starts listing her multitude of undertakings. The founder of Weex Tall, a Dakar studio that consolidates her various activities, and the co-founder of Lives, a platform promoting African destinations, she has also created a documentary series and various fashion collaborations; works at the Senegalese government’s Office of Architecture and Conservation of National Palaces; and represents the French firm Wilmotte & Architects in Dakar (it has an HQ for the United Nations, as well as several restoration projects, underway).

Atelier Worofila, Senegal

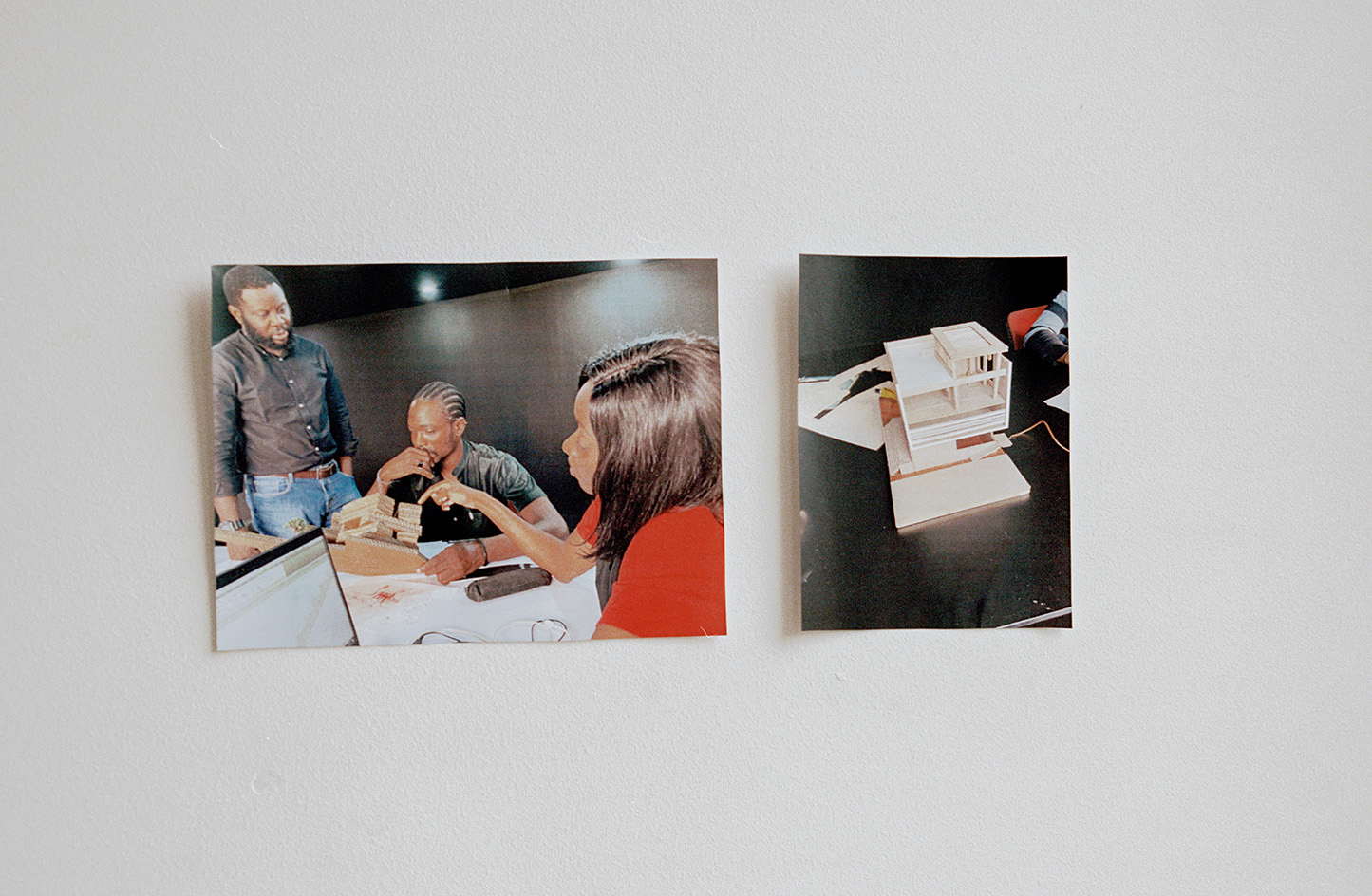

Atelier Worofila was first born as a collective in 2017 – five architects and engineers joined forces in Dakar, united by a competition entry. The group evolved over time and, by 2019, just two of the original founders remained: Nzinga Mboup and Nicolas Rondet, who established the studio in its current form.

Atelier Worofila is now an eight-strong practice that thrives in its multidisciplinary and hyper-local approach. ‘Our aim is to work with local materials, climate and skills,’ says Rondet. ‘Our name, inspired by our location, reflects that. It is also a street in a lovely, old, preserved part of Dakar [the Fann-Hock area] and we feel it highlights our approval for this urbanistically beautiful area.’ The pair practise and build (past and current works include villas, public amenities and the renovation of the courtyard and art gallery for the French Institute in Dakar), but also spend a lot of time on extracurricular activities such as curating and teaching.

Atelier Inhyah, Côte d’Ivoire

Atelier Inhyah is a story of two friends, Assarah Adoum from Chad and Tara-Aude Koffi from Côte d’Ivoire. They graduated from the École Spéciale d’Architecture de Paris in 2019, and went on to work for French and Ivorian firms. But they both felt the need to create a practice relevant to their cultural backgrounds and decided to start their own firm in 2020: ‘We are inspired by where we are from, while being relevant to our time.’

They chose to settle in Abidjan, ‘a subSaharan hub for architecture, despite having had its share of issues to address,’ as Koffi describes it. Aside from more traditional projects, Inhyah is interested in creating a sustainable ecosystem that would benefit local craftspeople. ‘We created a line of home accessories and furniture for that reason,’ Koffi explains. ‘We want people to understand that contemporary architecture answers to its time, yes, but also to its place.’

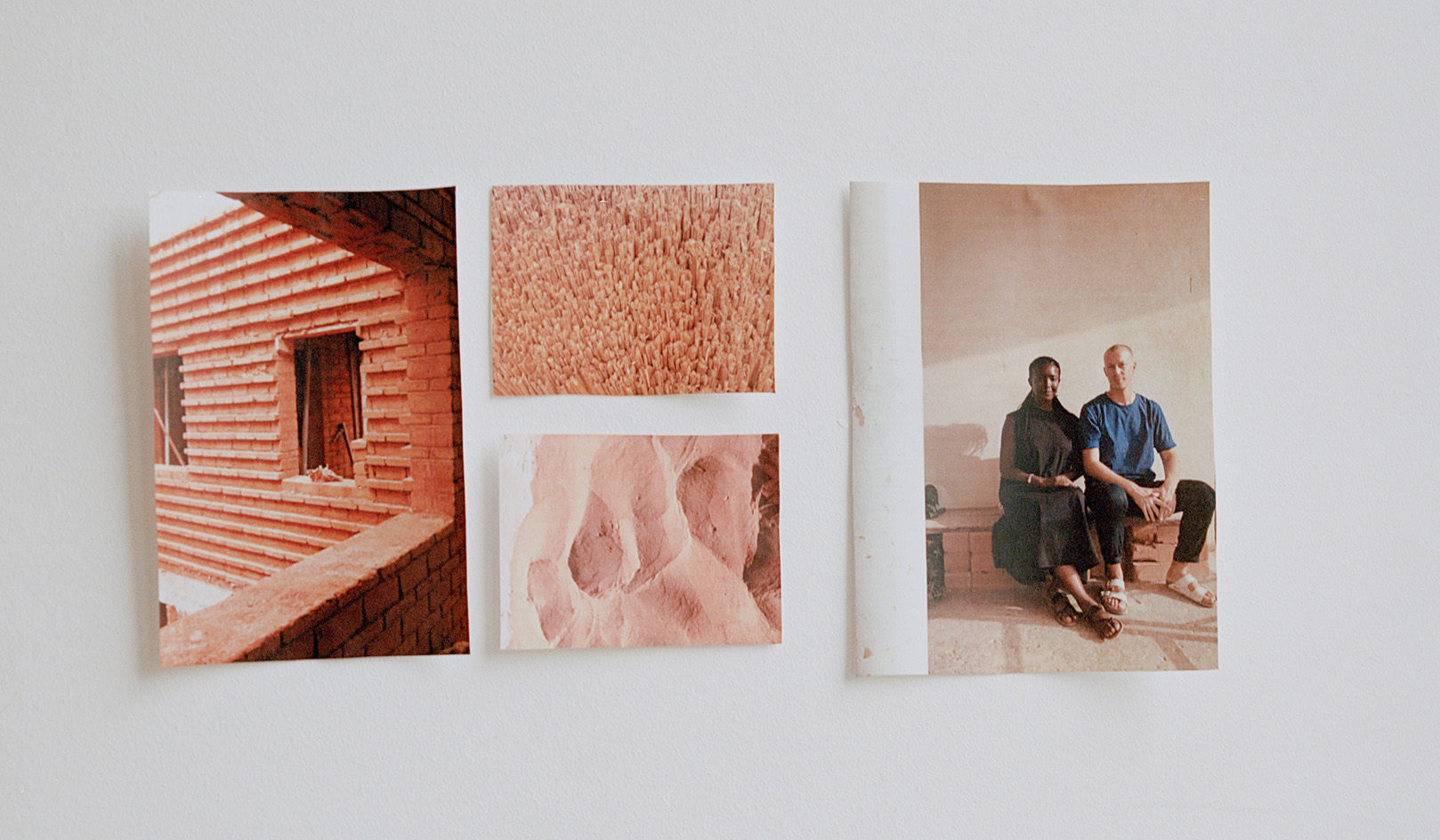

Hive Earth, Ghana

Although not quite an architecture studio, Hive Earth is a crucial player in its field, as its pioneering rammed-earth construction methods have the potential to transform architecture and construction practices in Ghana and beyond. The outfit was formally established in 2017 by Joelle Eyeson and Kwame Deheer, but the husband-and-wife team have been researching the topic together for decades. United by their passion for eco-friendly construction, UK-born and raised Eyeson and Ghanaian Deheer set up Hive Earth to combine sustainability and African ways of building.

‘We want to change the narrative of building with earth,’ says Eyeson. ‘It’s often associated with building for the poor, but it can look beautiful and is very eco-friendly. Rammed earth is a continuation of the traditional African mud home, so we feel like we are evolving that concept.’

CM Design Atelier, Nigeria

Tosin Oshinowo is a multitasking powerhouse – and as she starts listing her recent creative exploits, it is clear that the Lagos-based architect has been busy. ‘I am an architect first, though I am involved in other aspects of the creative industry,’ she explains. ‘I head up a studio, CM Design Atelier, which employs ten architects, designers and project managers, and I have a furniture line called Ilé-Ilà. I also sit on the board for the Lagos Theatre Festival and co-curated the 2019 Lagos Biennial, and I am currently curating the 2023 Sharjah Architecture Triennial.’

Educated in the UK, Oshinowo feels her work is ‘grounded in a deep respect for my native Yoruba culture,’ she says. Fusing modernism with the African context has been a lifelong project for her. This has resulted in work that she describes as ‘afrominimalist’, celebrating West African design and culture, and supporting and promoting the region’s rich traditions. ‘Whether I am curating the Triennial or designing beach houses – everything I do is to celebrate the people, culture, talent and traditions of my region,’ she says. ‘I aim to demonstrate to the world that we are an overlooked significant potential, with solutions, practices and ideas.’

HTL Africa, Nigeria

HTL Africa is an ‘idea factory’ according to its founder James George, who established the architecture practice in 2011. ‘I like to look at it as a group of people who collaborate to make working megacities,’ George says of the team of 11 who make up the firm. At the heart of the practice is a focus on performance: ‘Globally in architecture, there’s no understanding that buildings are objects of performance. I think beauty is not important in the sense that we make it important. Architecture must engage with the environment in a way that enhances it, and in a way that creates the opportunity for people to have equality and change.’

George trained at Ahmadu Bello University in the northern Nigerian state of Zaria – an institution he says ‘gave him the independence to learn on his own terms’. His breakthrough project was the 32,000 sq ft Green Wall multistorey office block in downtown Lagos, completed in 2017.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

The World Monuments Fund has announced its 2025 Watch – here are some of the endangered sites on the list

The World Monuments Fund has announced its 2025 Watch – here are some of the endangered sites on the listEvery two years, the World Monuments Fund creates a list of 25 monuments of global significance deemed most in need of restoration. From a modernist icon in Angola to the cultural wreckage of Gaza, these are the heritage sites highlighted

By Anna Solomon

-

Lesley Lokko reviews 2024's wins, shifts, tensions and opportunities for 2025

Lesley Lokko reviews 2024's wins, shifts, tensions and opportunities for 2025Lesley Lokko, the British-Ghanaian architect, educator, curator, and founder and director of the African Futures Institute (AFI), has been an inspirational presence in architecture in 2024; which makes her perfectly placed to discuss the year, marking the 2025 Wallpaper* Design Awards

By Lesley Lokko

-

Limbo Museum: celebrating the architectural legacy of ‘unfinished business’

Limbo Museum: celebrating the architectural legacy of ‘unfinished business’We’re won over by Limbo Museum and the work of Limbo Accra, which is bringing new life to abandoned buildings across West Africa, and wins a Wallpaper* Design Award 2025

By Shawn Adams

-

‘Architecture Encounters’ traces period-defining built environment stories in Togo and West Africa

‘Architecture Encounters’ traces period-defining built environment stories in Togo and West Africa‘Architecture Encounters’ (Les Rencontres Architecturales de Lomé) in Togo celebrates and explores West Africa’s rich heritage through the prism of conservation and transformation, kicking off with two days of talks, workshops, exhibitions and tours at Palais de Lomé

By Ijeoma Ndukwe

-

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practices

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practicesIn the Wallpaper* Architects Directory 2024, our latest guide to exciting, emerging practices from around the world, 20 young studios show off their projects and passion

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Nigerian architects SI.SA draw on 'simplicity, clarity, and unity'

Nigerian architects SI.SA draw on 'simplicity, clarity, and unity'SI.SA, a young Nigerian practice, is featured in the Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024; tour its Scissor House in Ikoyi, an elegant solution to a constrained plot

By Shawn Adams

-

Toshiko Mori's well-connected community centre in rural Senegal has high ambitions

Toshiko Mori's well-connected community centre in rural Senegal has high ambitionsToshiko Mori gives a talk introducing 16- to 25-year-olds to architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts in London tonight; to mark the occasion we revisit her 2015 community centre in rural Senegal

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Dot.ateliers | Ogbojo is an 'oasis' for writers and curators in Ghana

Dot.ateliers | Ogbojo is an 'oasis' for writers and curators in GhanaDot.ateliers | Ogbojo in Accra, Ghana was designed by emerging studio DeRoché Strohmayer for artist Amoako Boafo as a writer’s and curator’s residency space for the country's creatives

By Ellie Stathaki