MoMA proves that Frank Lloyd Wright still has it, even at 150

Although Frank Lloyd Wright died more than half a century ago (his 150th birthday would have been on 8 June), he remains the most famous architect in the world. It’s easy to see why when you explore the Museum of Modern Art’s new exhibition, ‘Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive’.

The sprawling show features almost 400 works by the American master, ranging from drawings, models, furniture and print media all the way to tableware and pieces of buildings. It was sparked by the herculean task of ushering the archive’s more than 55,000 drawings, 125,000 photos, and much more from Taliesen West to MoMA.

But much more than that, describes curator Barry Bergdoll, it’s about bringing in new voices to examine the work and impact of this most impactful of architects. Bergdoll invited more than a dozen scholars and conservators to unpack (as per the show’s title – a double entendre) varied themes around Wright’s work. What they’ve found reveals that the archive, as Bergdoll puts it, continues to ‘unfold new experiments’, and will continue to do so for generations.

Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, 1955–61, pastel and pencil on paper, by Frank Lloyd Wright. Stained glass design by Eugene Masselink

Revelation comes regularly as you explore the 12 divided sections of the show – focusing on drawings and abstract representations over photographs – from his well-documented experiments in ornament, structure, and building systems to his relatively unknown research in urbanism and farming. Other galleries touch on landscape, the Native American-inspired Nakoma Golf Club near Madison, Wicsonsin, and his proposed blade-like mile high tower for Chicago, meant to shore up his bonifides as he lobbied to take part in the city’s building boom.

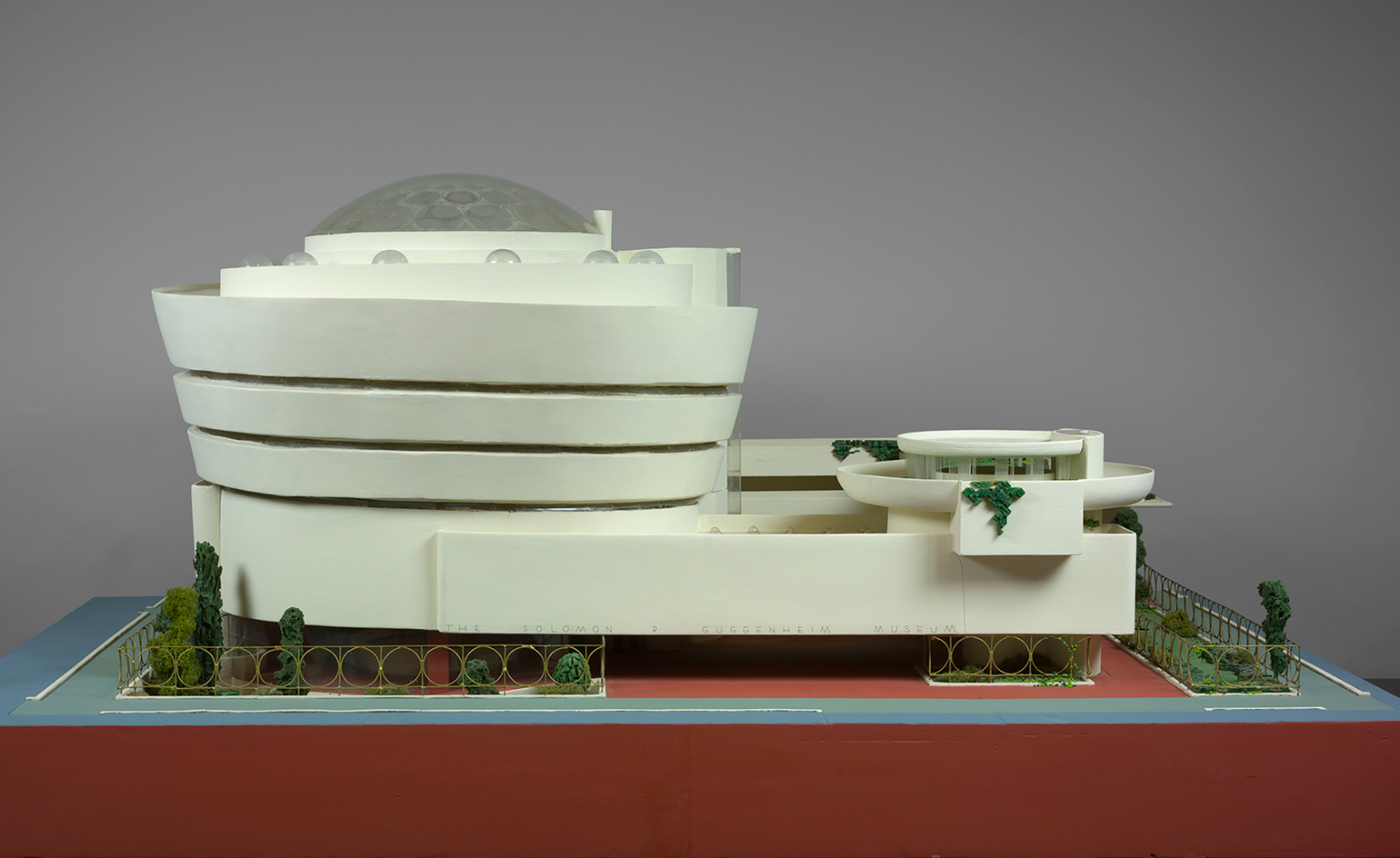

As you chew on the seemingly endless themes, it’s impossible not to marvel at the skill and seduction of the drawings and artifacts, from a surprising neoclassical competition rendering for the Milwaukee Public Library in the 1890s to the space aged, dome and bubble concoctions of the 1950s. Everything is art: elaborate and colorful architectural sections and plans are just as much artwork as the intricate stained glass windows, hexagonal chairs, and concentric-sphere murals nearby. All is unified, wondrously held together through Wright’s organic ideals and his commitment to (whether his clients liked it or not) total design.

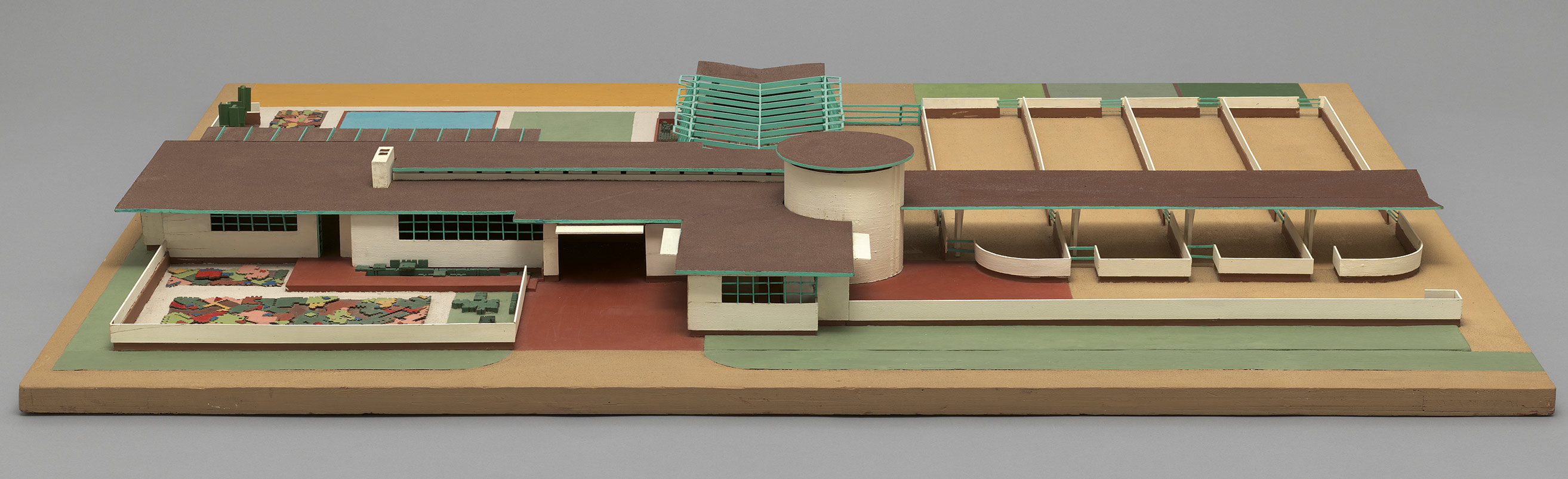

Davidson Little Farms Unit, model in painted wood and particle board, 1932–33, by Frank Lloyd Wright

And while the architect was light years ahead of his time, exploring complex technological and formal systems that most around him couldn’t keep up with (which explains, to a point, all the cracks and leaks), he was able to create spaces, systems, and pieces that almost anyone could appreciate. Wright’s work is universal both in its ability to hold together in all its variation, and in its ability to seamlessly connect to the world at large.

This combination of complexity and accessibility, the show drives home, continues to mesmerise the general public. Perhaps even more than the architectural establishment. The show, says Bergdoll, is basically a billboard to encourage scholars and visitors alike to continue to tease out lessons from it all.

‘The goal here is to announce that the archive is here and open to new questions and new people,’ says Bergdoll. For Wright, the quintessential self-promoter, all this broadcasting, and yes, fame, would have been just fine.

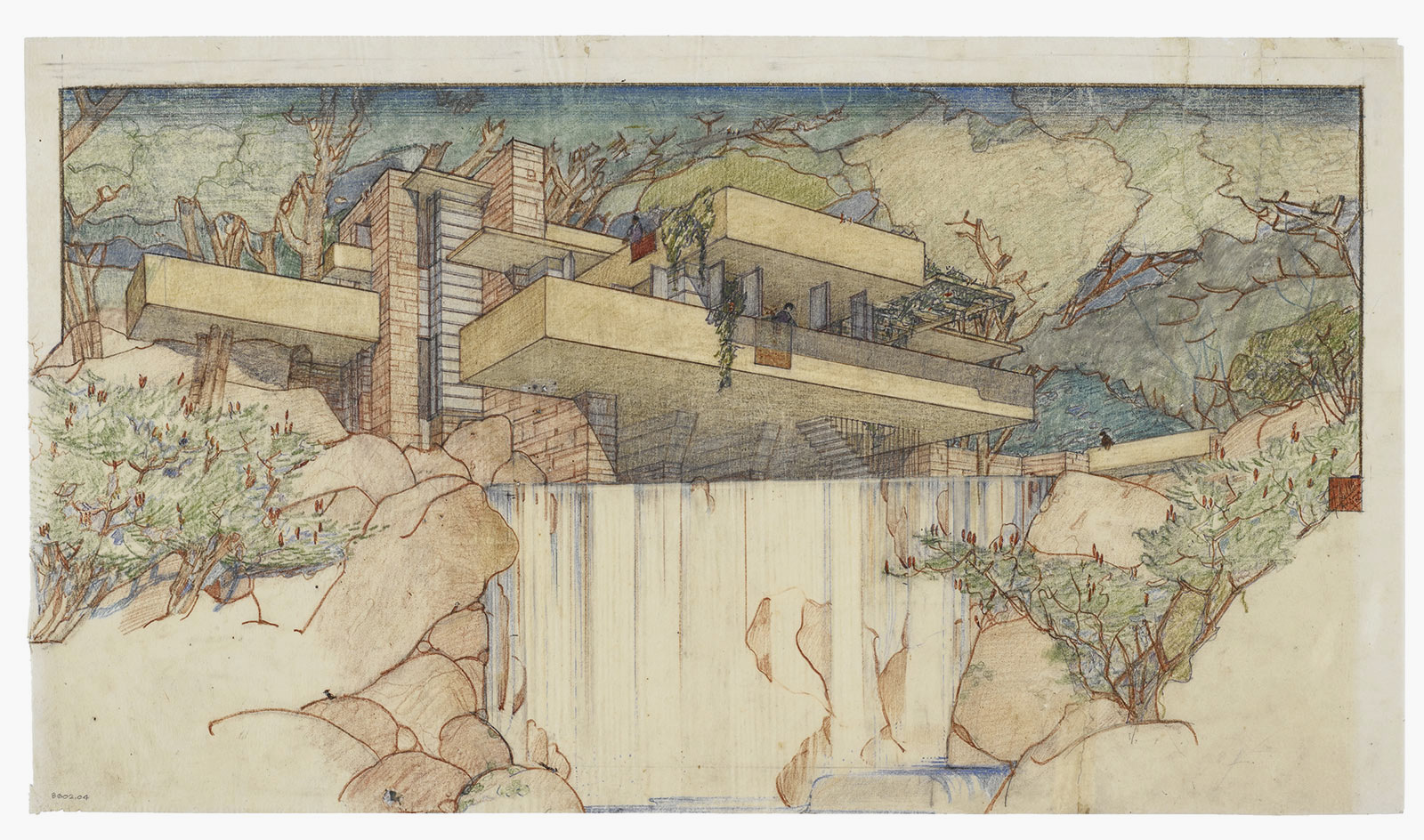

Pencil and colored pencil on paper drawing of Wright’s Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania, 1934–37

A drawing by Wright based on a circa 1926 design for Liberty magazine in coloured pencil on paper, titled March Balloons, 1955

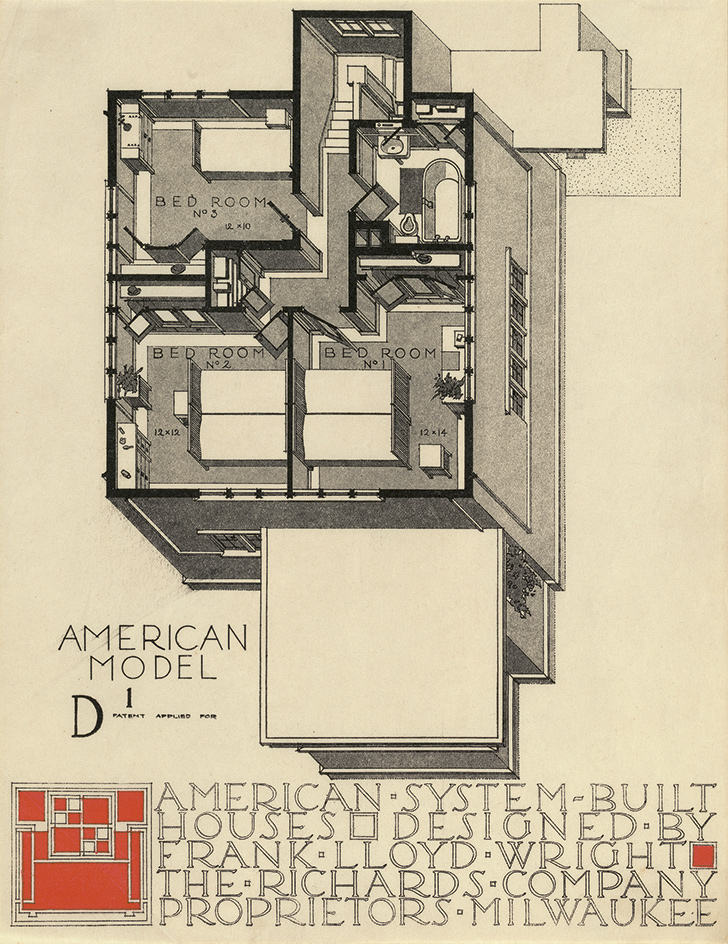

Lithograph of the American System-Built (Ready-Cut) Houses project from 1915–17. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gifts of David Rockefeller Jr Fund, Ira Howard Levy Fund, and Jeffrey P. Klein Purchase Fund

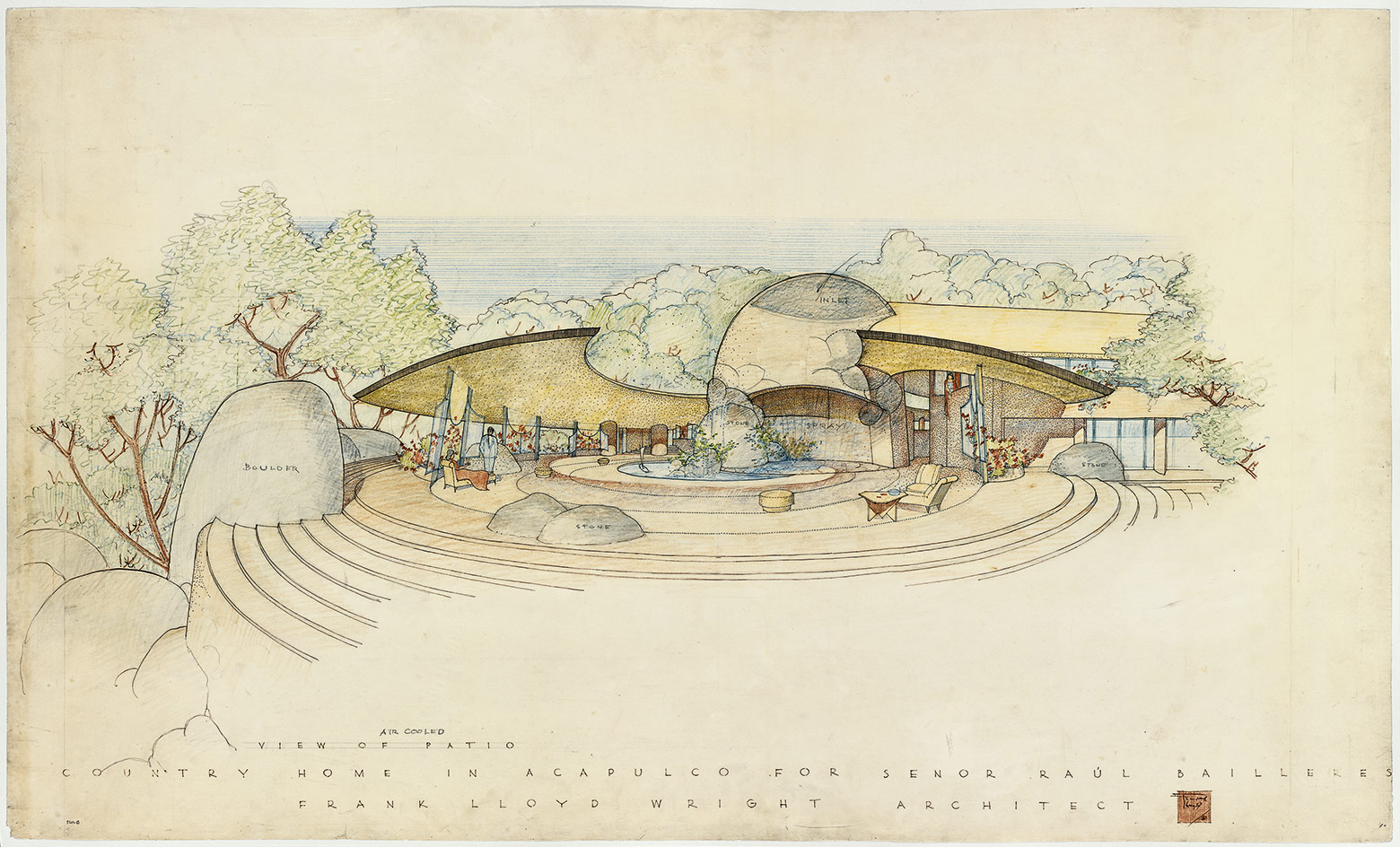

Raul Bailleres House, Acapulco, Mexico project. Perspective from the patio in ink, pencil, and coloured pencil on tracing paper, 1951–52

The Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland, 1924–25

Model of St Mark’s Tower, an unbuilt project for New York, 1927-31, in painted wood

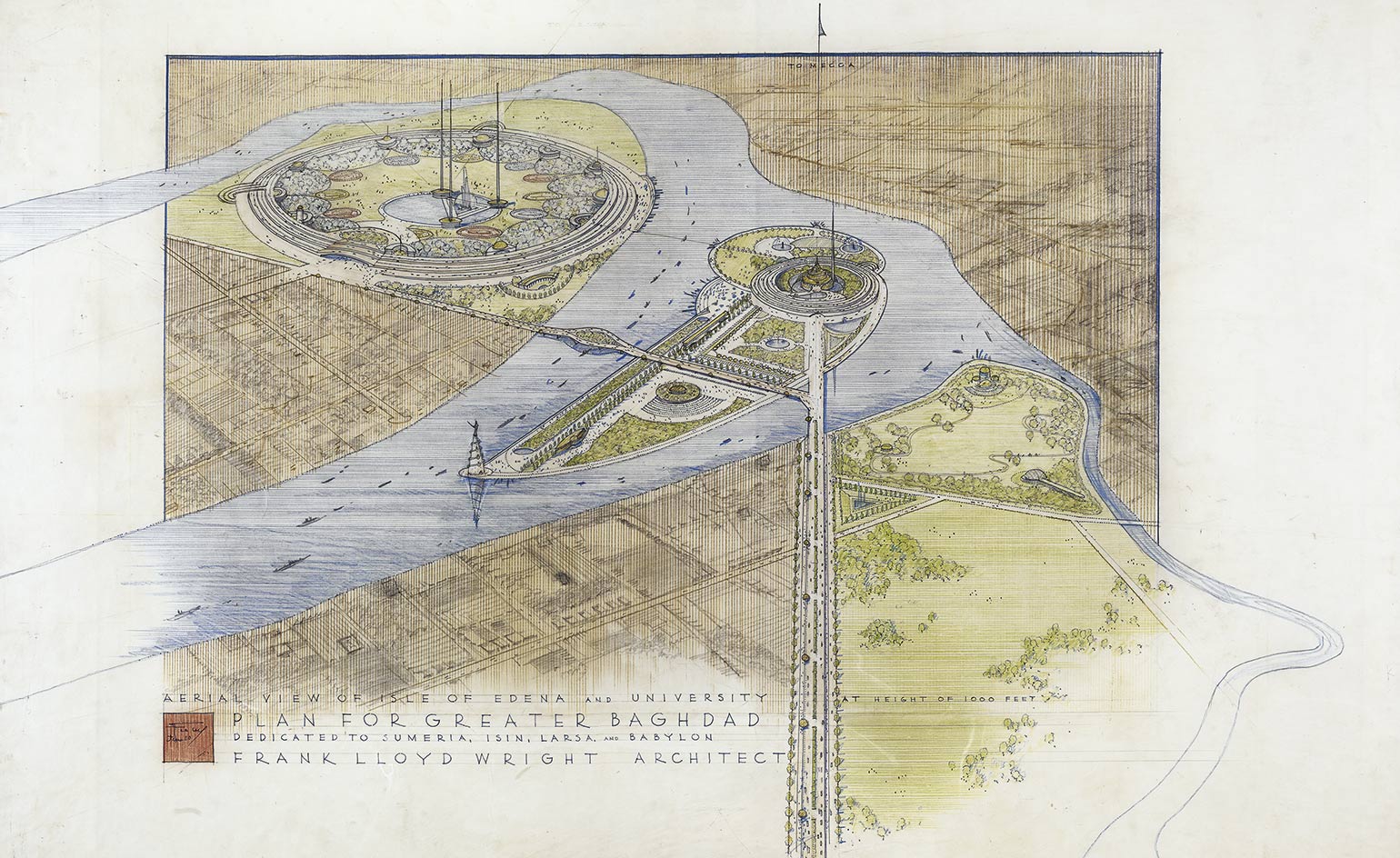

Aerial perspective of the cultural centre and university from the north, 1957, part of the plan for Greater Baghdad, in ink, pencil, and coloured pencil on tracing paper

INFORMATION

‘Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive’ is on view until 1 October. For more information, visit the MoMA website

ADDRESS

MoMA

11 W 53rd Street

New York

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yoursJean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

By Amy Serafin

-

We explore Franklin Israel’s lesser-known, progressive, deconstructivist architecture

We explore Franklin Israel’s lesser-known, progressive, deconstructivist architectureFranklin Israel, a progressive Californian architect whose life was cut short in 1996 at the age of 50, is celebrated in a new book that examines his work and legacy

By Michael Webb

-

A new hilltop California home is rooted in the landscape and celebrates views of nature

A new hilltop California home is rooted in the landscape and celebrates views of natureWOJR's California home House of Horns is a meticulously planned modern villa that seeps into its surrounding landscape through a series of sculptural courtyards

By Jonathan Bell

-

The Frick Collection's expansion by Selldorf Architects is both surgical and delicate

The Frick Collection's expansion by Selldorf Architects is both surgical and delicateThe New York cultural institution gets a $220 million glow-up

By Stephanie Murg

-

Remembering architect David M Childs (1941-2025) and his New York skyline legacy

Remembering architect David M Childs (1941-2025) and his New York skyline legacyDavid M Childs, a former chairman of architectural powerhouse SOM, has passed away. We celebrate his professional achievements

By Jonathan Bell

-

What is hedonistic sustainability? BIG's take on fun-injected sustainable architecture arrives in New York

What is hedonistic sustainability? BIG's take on fun-injected sustainable architecture arrives in New YorkA new project in New York proves that the 'seemingly contradictory' ideas of sustainable development and the pursuit of pleasure can, and indeed should, co-exist

By Emily Wright

-

The upcoming Zaha Hadid Architects projects set to transform the horizon

The upcoming Zaha Hadid Architects projects set to transform the horizonA peek at Zaha Hadid Architects’ future projects, which will comprise some of the most innovative and intriguing structures in the world

By Anna Solomon

-

Frank Lloyd Wright’s last house has finally been built – and you can stay there

Frank Lloyd Wright’s last house has finally been built – and you can stay thereFrank Lloyd Wright’s final residential commission, RiverRock, has come to life. But, constructed 66 years after his death, can it be considered a true ‘Wright’?

By Anna Solomon