David Gill’s tribute to Zaha Hadid recalls her idiosyncratic oeuvre and enlightening spirit

I first met Zaha back in the 1980s. Zaha had already set up her own architectural practice and I had just left Christie's and was on the cusp of opening my own gallery. During that era London really felt like the hub of global creativity. The city was emerging from the social, economic and political gloom of the 1970s and was rapidly taking over from Paris. Zaha had grown up during turbulent times in her home country of Iraq, but for her, like many of us, it was London where she finally settled. It was London that seemed to offer all the chances and possibilities to the creative, ambitious individuals that we all were.

Zaha was always someone whose drive and vision were readily apparent. You instantly knew you were in the presence of a woman who was going to change the world. In 1988 when MoMA featured her work in the show 'Deconstructivism in Architecture,' curated by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley, it really felt as though a stamp of official acceptance had been given to her work. What had always been considered the furthest edge of the extreme avant-garde of architecture was at last edging into the light.

Throughout her career Zaha continued to push expectations of what we thought could be possible. Both as an architect and as a designer, she understood the cult of the personality and realised that she had to be visible to win projects on a global stage. She understood that it was her very individualism that was the key to pushing her practice and her theories of architecture and design forwards to a wider audience. Whether designing sets for major pop acts or working in fashion, from creating furniture that was seemingly unimaginable to appearing on Desert Island Discs – Zaha always understood that it was her visibility across a multitude of platforms – not just the architectural - that would ultimately allow an international audience to embrace both her and her work.

Zaha was always well aware that being a woman, in what was often considered a man’s world, offered an inherent set of issues, both as an architect and as a businesswoman. But as with everything, she only saw this as another challenge she had to overcome and triumph. Through her indomitable spirit she won contracts all over the world and she pushed our very beliefs in what shape and space could be – whether in a building or a table. She threw away traditional ideas of form and function and she made us all catch our breath whenever we saw her work. Everything she touched, whatever it was, you always knew that it was from the hand of Zaha.

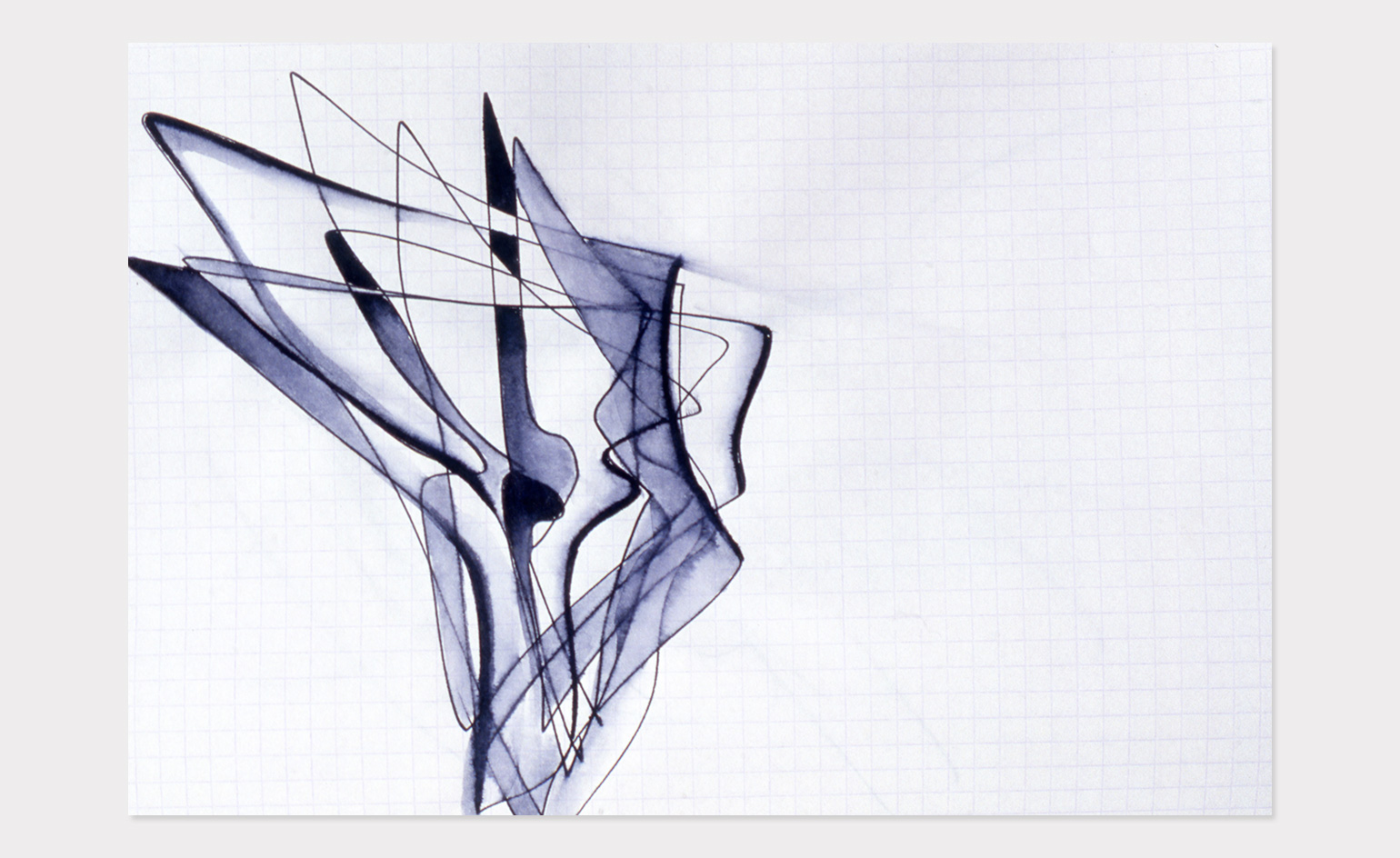

An inkdrawing from the sketchbook of Hadid, made in 2001

When we first began to talk about working together, it was typically Zaha. She didn’t want to launch in London, she wanted to unveil her first collection – Dune Formations – at the Venice Art Biennale in 2007. The result was incredible and together we showed the world an interior landscape that confounded the very ideas of what furniture could be. The pieces bled from the vertical to the horizontal and tore up the book in terms of what was possible with 3D modelling at that time.

That collection set up a relationship between Zaha and David Gill Gallery with collections that examined materials such as metals, resins and acrylic offering an assault on what was considered possible for furniture and the conventional laws of design. It seems almost poignant however that her final collection which we launched this autumn actually revealed Zaha to be looking back in time, towards the 1950s and 1960s working in more traditional materials such as woods and leather. The shapes still offer a dialogue in the aesthetics of flow, but the materials perhaps show a slightly different side.

I miss Zaha terribly, not only because of her genius but also for her unending spirit to seek and discover, to experiment and to never give up. Every generation is lucky to lay claim to a small collection of truly creative talents, people and minds that will leave an indelible mark on the world that they leave behind them. Zaha is one of that small group, one that our generation can say has truly changed our lives and our world for the better.

We will miss her vision, we will miss her laugh but more than anything we will miss our very dear friend.

INFORMATION

‘Zaha Hadid’ is on view until 12 February 2017. For more information, visit the Serpentine Gallery website

ADDRESS

Kensington Gardens

W Carriage Dr

London W2 2AR

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

The work of Salù Iwadi Studio reclaims African perspectives with a global outlook

The work of Salù Iwadi Studio reclaims African perspectives with a global outlookWallpaper* Future Icons: based between Lagos and Dakar, Toluwalase Rufai and Sandia Nassila of Salù Iwadi Studio are inspired by the improvisational nature of African contemporary design

-

Top 25 houses of 2025, picked by architecture director Ellie Stathaki

Top 25 houses of 2025, picked by architecture director Ellie StathakiThis was a great year in residential design; Wallpaper's resident architecture expert Ellie Stathaki brings together the homes that got us talking

-

Year in review: the shape of mobility to come in our list of the top 10 concept cars of 2025

Year in review: the shape of mobility to come in our list of the top 10 concept cars of 2025Concept cars remain hugely popular ways to stoke interest in innovation and future forms. Here are our ten best conceptual visions from 2025

-

Oystra is ZHA’s sculptural vision for living in the United Arab Emirates

Oystra is ZHA’s sculptural vision for living in the United Arab EmiratesMeet the team translating ZHA’s bold concept for the new development into ‘a community elevated by architecture’ – Dewan Architects + Engineers and developer Richmind

-

The Zaha Hadid Foundation announces a new programme to support emerging architects

The Zaha Hadid Foundation announces a new programme to support emerging architectsThe Zaha Hadid Scholars Program will fully fund two architecture students per year for the duration of their studies at the American University of Beirut

-

Zaha Hadid Architects’ spaceship-like Shenzhen Science and Technology Museum is now open

Zaha Hadid Architects’ spaceship-like Shenzhen Science and Technology Museum is now openLast week, ZHA announced the opening of its latest project: a museum in Shenzhen, China, dedicated to the power of technological advancements. It was only fitting, therefore, that the building design should embrace innovation

-

The upcoming Zaha Hadid Architects projects set to transform the horizon

The upcoming Zaha Hadid Architects projects set to transform the horizonA peek at Zaha Hadid Architects’ future projects, which will comprise some of the most innovative and intriguing structures in the world

-

Zaha Hadid Architects reveals plans for a futuristic project in Shaoxing, China

Zaha Hadid Architects reveals plans for a futuristic project in Shaoxing, ChinaThe cultural and arts centre looks breathtakingly modern, but takes cues from the ancient history of Shaoxing

-

Zaha Hadid Architects’ new project will be Miami’s priciest condo

Zaha Hadid Architects’ new project will be Miami’s priciest condoConstruction has commenced at The Delmore, an oceanfront condominium from the firm founded by the late Zaha Hadid, ZHA

-

AI in architecture: Zaha Hadid Architects on its pioneering use and collaborating with NVIDIA

AI in architecture: Zaha Hadid Architects on its pioneering use and collaborating with NVIDIAWe talk to ZHA about AI in architecture, its computational design advances, and its collaboration with NVIDIA on design, data and the future of AI and creativity

-

Omniyat launches The Alba, new Zaha Hadid Architects-designed residences in Dubai

Omniyat launches The Alba, new Zaha Hadid Architects-designed residences in DubaiDeveloper Omniyat announces The Alba, ultra-luxury residences managed by Dorchester Collection and designed by Zaha Hadid Architects to blend ‘nature and cutting-edge design’