Estudio MMX’s Geology Museum on the Yucatán Peninsula is a big hit

Estudio MMX’s new crater-inspired Geology Museum on the Yucatán Peninsula is sure to be a big hit

Dane Alonso - Photography

Mexico’s many claims to fame include a rich culture, a long history and dramatic landscapes. It is lesser known, however, as the site of an important event that changed life on Earth for ever. Yet it is here that the asteroid that is thought to have killed the dinosaurs landed, heralding a new era for the planet and leaving in its path what today is known as the Chicxulub crater. Located on the Yucatán Peninsula, this geological formation was the result of an impact that happened 66 million years ago. It is also the inspiration for a new museum in the small seaside town of Progreso, designed by Estudio MMX, a dynamic and relatively young Mexico City-based practice founded in 2010 by architects Jorge Arvizu, Ignacio del Río, Emmanuel Ramírez and Diego Ricalde.

Created as part of an ambitious national scheme called Programa de Mejoramiento Urbano (PMU), or Urban Improvement Programme, which kick-starts public projects and cultural interventions in cities across the country, the new Geology Museum focuses on the region’s rich history in the field.

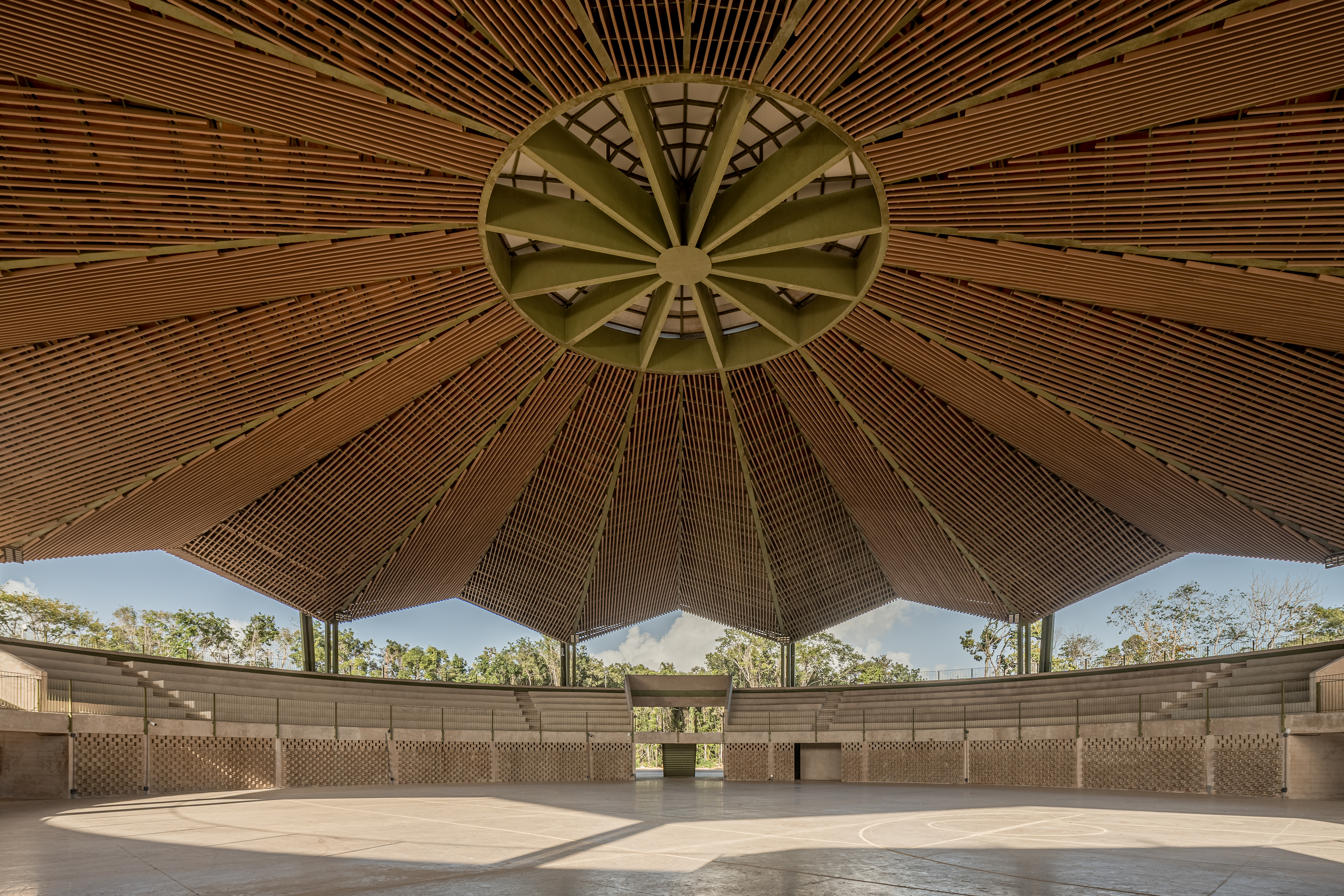

Openings allow the sea breeze to travel across the site, helping to cool the building naturally, and making the structure more resilient to the hurricanes that often hit Progreso in the summer

The initial plan was to build a new cultural building for Progreso, but its exact use was unclear at the start of the project in 2019: ‘They told us, there is an opportunity to make this cultural space, in this part of Yucatán. We were put forward as the architects for this site as well as another project, the market in neighbouring Chicxulub,’ Ricalde recalls. ‘Because of the crater of the asteroid that hit the Earth and extinguished the dinosaurs, it was then decided to do something around geology.’

This is a rural and fertile part of the country, both in nature and history. Yucatán’s capital, Mérida, is just 50km south and the area is filled with mangroves and dotted with sandy strips and Mayan and colonial heritage sites. It also used to be the main producer of henequen, a variety of the agave plant often referred to as ‘green gold’ for its uses in the textile industry. Both the geology of the impact crater and the existing natural environment played a key role in the design development of the new museum. Its distinct form is composed as a sequence of discrete yet interconnected square-ish volumes set on a strict, geometric grid spread across the length and width of the site. The angled arches and overall monolithic and stepped character of the volumes reference ancient Mayan architecture, the architects explain.

The museum includes a series of water features inspired by Yucatán’s cenotes, the sinkholes created by the asteroid impact 66 million years ago

The building is covered in a type of plaster called chukum, a traditional material made with the powdered bark of a small thorny tree of the same name. It allows for great detailing, is locally produced, naturally water-resistant, and soft to the touch. ‘It fits the city’s urban image, as well as the landscape’s colours, and its light tone reflects the sunrays and helps control the heat,’ Ricalde explains. ‘As for the grid, it is a very common feature in the cities in this part of Mexico, many of which were built around orthogonal grids.’

Inside, the building has space for offices, temporary and permanent exhibitions, a café and multifunctional areas for workshops, educational programmes and events. ‘As we didn’t know from the start what exactly would be housed within, we had to design the building to be flexible,’ the architect says.

Ricalde also points out that the height of each volume is designed so that there is an undulation, abstractly referencing the topography of a crater. At the same time, openings underneath some of these elements allow the sea breeze to travel across the site, cooling down the building naturally, while a green garden below invites the local wildlife in, offering a mix of water features and native plants. The fact that much of the building is lifted above ground level also helps it negotiate rising water, as the area is prone to flooding. And thick shading created by the various, closely knit spaces is welcome in the outdoor public space as it protects it from the sun in this typically hot region.

The museum is spread in a series of blocks arranged in a grid. Their triangular openings recall the shape of the region’s Mayan pyramids

While the site is big, the building is not very tall, ensuring that it does not block the views towards the sea or dominate the lower urban fabric around it. ‘There are many hurricanes in the summer season and so, instead of making one big solid building that would ‘fight’ the winds, by breaking it down, the winds can feel softer and the building is more resilient,’ the architect continues.‘The vegetation was also important to us. We love incorporating plants in architecture, and we are very interested in the relationship between landscape and architecture. The species selection was done carefully so the design would act according to our intentions, saving existing palms while avoiding inserting non-native species or creating maintenance issues. It’s very important for us in every project, but particularly in this one, as previously the site hosted what was an open public space. In our view, the city did not lose a park – it gained a museum.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

INFORMATION

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

The new Tudor Ranger watches master perfectly executed simplicity

The new Tudor Ranger watches master perfectly executed simplicityThe Tudor Ranger watches look back to the 1960s for a clean and legible design

-

This late-night hangout brings back 1970s glam to LA’s Sunset Boulevard

This late-night hangout brings back 1970s glam to LA’s Sunset BoulevardGalerie On Sunset is primed for strong drinks, shared plates, live music, and long nights

-

How Memphis developed from an informal gathering of restless creatives into one of design's most influential movements

How Memphis developed from an informal gathering of restless creatives into one of design's most influential movementsEverything you want to know about Memphis Design, from its history to its leading figures to the pieces to know (and buy)

-

Aidia Studio's mesmerising forms blend biophilia and local craft

Aidia Studio's mesmerising forms blend biophilia and local craftMexican architecture practice Aidia Studio's co-founders, Rolando Rodríguez-Leal and Natalia Wrzask, bring together imaginative ways of building and biophilic references

-

Mexico's Palma stays curious - from sleepy Sayulita to bustling Mexico City

Mexico's Palma stays curious - from sleepy Sayulita to bustling Mexico CityPalma's projects grow from a dialogue sparked by the shared curiosity of its founders, Ilse Cárdenas, Regina de Hoyos and Diego Escamilla

-

Discover Locus and its ‘eco-localism' - an alternative way of thinking about architecture

Discover Locus and its ‘eco-localism' - an alternative way of thinking about architectureLocus, an architecture firm in Mexico City, has a portfolio of projects which share an attitude rather than an obvious visual language

-

Deep dive into Carlos H Matos' boundary-pushing architecture practice in Mexico

Deep dive into Carlos H Matos' boundary-pushing architecture practice in MexicoMexican architect Carlos H Matos' designs balance the organic and geometric, figurative and abstract, primitive and futuristic

-

For Rodríguez + De Mitri, a budding Cuernavaca architecture practice, design is 'conversation’

For Rodríguez + De Mitri, a budding Cuernavaca architecture practice, design is 'conversation’Rodríguez + De Mitri stands for architecture that should be measured, intentional and attentive – allowing both the environment and its inhabitants to breathe

-

Mexico's Office of Urban Resilience creates projects that cities can learn from

Mexico's Office of Urban Resilience creates projects that cities can learn fromAt Office of Urban Resilience, the team believes that ‘architecture should be more than designing objects. It can be a tool for generating knowledge’

-

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craft

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craftGuadalajara architects Laura Barba and Luis Aurelio of Barbapiña Arquitectos design drawing on the past to imagine the future

-

This Mexican architecture studio has a surprising creative process

This Mexican architecture studio has a surprising creative processThe architects at young practice Pérez Palacios Arquitectos Asociados (PPAA) often begin each design by writing out their intentions, ideas and the emotions they want the architecture to evoke