Jørn Utzon’s travel diaries and photography reveal the conceptual thinking behind his work

As part of the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of architect Jørn Utzon’s birth, the Utzon Center in Aalborg, Denmark, follows the international travels of the Danish architect who designed the Sydney Opera House through personal photography, architectural models and ephemera. The Utzon Center, which was Utzon’s last building project, also happens to be celebrating its 10th anniversary. Hence, there is plenty to celebrate.

While Aalborg was the place of Utzon’s birth, he left his hometown early in his career to build a home for his family just north of Copenhagen. He then travelled extensively for commissions or with travel grants to places such as Morocco and the US, rellocated to Sydney with his family for the Opera House project and then returned to Mallorca to set up a family home. Curator Line Nørskov Eriksen, who has a PhD in the architect’s work and had access to the Utzon Archive held by the city of Aalborg and the Utzon family, pieced together this journey through Utzon’s photographs, travel diaries, models, sketches and letters tracing the influence of his travels on his landmark works and the concepts that drove him.

Walking around, the exhibition lights of up a pathway of sound, colour and video, triggered by your footsteps. Utzon’s photographs are projected onto the walls in sets and his Super 8 films capture animated stories of diverse cultures, people and landscapes.

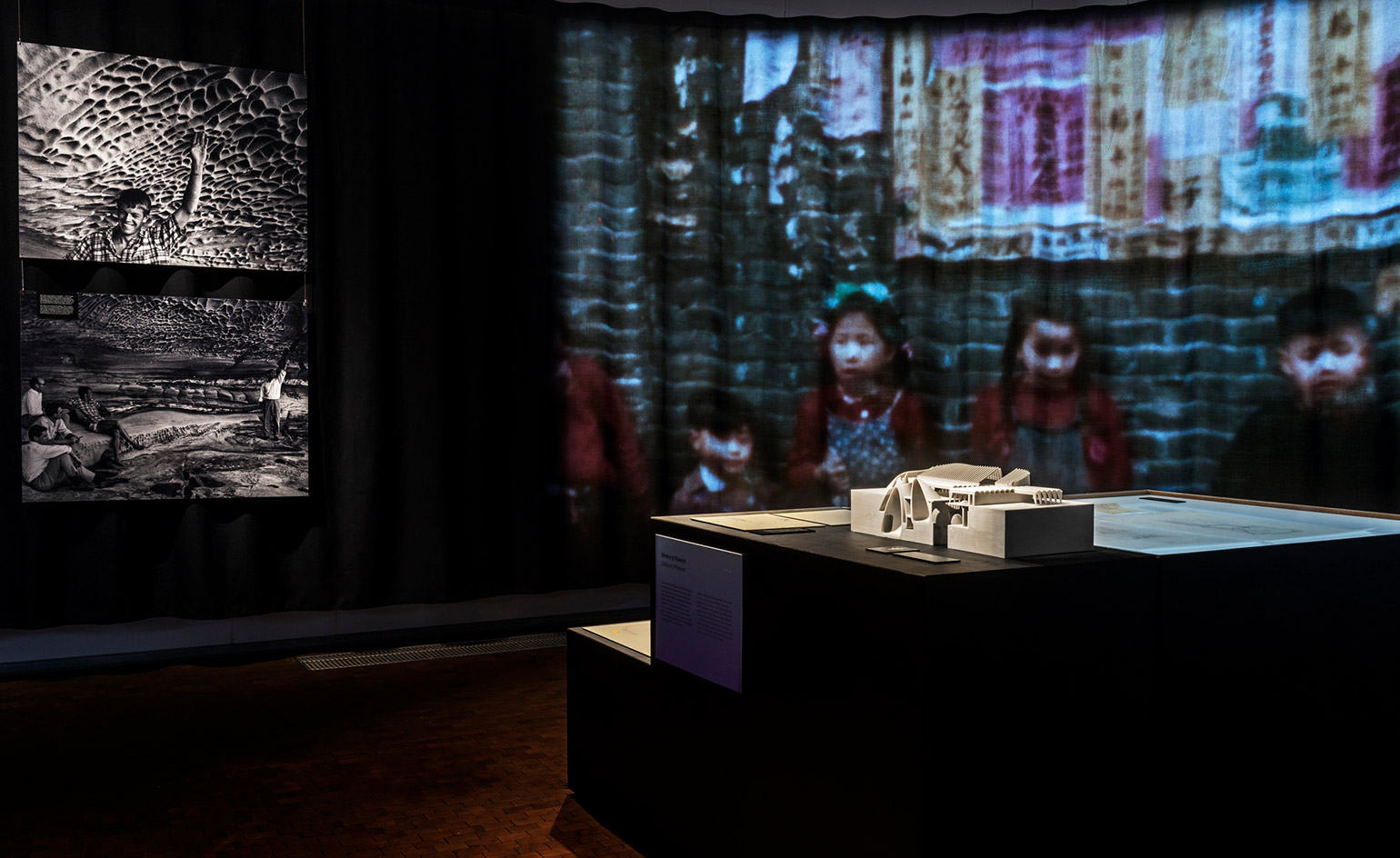

The exhibition installation of Horisont at the Utzon Center in Aalborg

This visual and experiential approach to understanding his work suits Utzon very well: ‘Utzon wasn’t the type of architect that enjoyed labels. He never formed a theory or said “my work is phenomenological” or “my work is semiological”. He was more interested in the work itself than the stuff around it,’ says Nørskov Eriksen.

‘In his photos you can see he was looking and searching, not just recording his surroundings,’ she says. ‘When you talk with people that knew him and his family, the one thing they always say is that he had this extremely amazing ability to look at the world around him and see countless lessons for architecture. His ability to observe and turn observation into an art form was really key to his work.’

Housing

Utzon began work in the context of post-war Scandinavia – described by Nørskov Eriksen as a time of scepticism of technology when there was an interest in returning to a simpler way of life. Utzon’s humane approach to architecture and sensitivity to the relationship between man and nature can be seen in the first house he built for his family, Hillebech house. It was a single-storey, low volume that stretched across a terrace on a sloped piece of land in a forest.

Linne explained the lack of drawings on show in the exhibition were due to the fact that the house was built on site with poles and canvasses. In tune with modernist principles of architecture and life, the house was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe and a travel scholarship to the US allowed him to visit Tallesin West and Falling Water – ‘He was quite interested in Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture. He worked with similar themes – the relationship between architecture and nature, drawing on primordial architecture in a modern sense,’ says Nørskov Eriksen.

Utzon’s daughter, Lin Utzon, lived for four years at Hellebæk house, and then later in Can Lis, the house in Mallorca Utzon designed for his family on their return from Sydney. She currently lives in Can Feliz, another house in Mallorca designed by her father. ‘We lived a different life,’ she says. ‘My parents were gearing towards a new world, they weren’t interested in living in the past. As a child, I grew up thinking things were possible, and that’s a fantastic gift to have been given. In his houses, I feel very surrounded by him and my mother, who was very much part of it. They were a team and she was indispensable – she was like a rock whatever was there.’

Can Lis in Mallorca, designed by Jørn Utzon for his family

The family house in Mallorca was named after Utzon’s wife, Lis, and Nørskov Eriksen made an effort to include her presence in the exhibition. It was Lis who typed up Utzon’s travel diaries that he would dictate to her. ‘I made sure to include lots of pictures of her because she was there all along. It takes two,’ says Nørskov Eriksen, who wanted to demonstrate their ‘immense love’ and partnership in life and work.

As well as single family homes, Utzon’s travels to Morocco in 1947 visiting rural communities influenced his communal housing design in Denmark – the Fredensborg and Kingo housing complexes in Denmark were informed by houses in – their layered plans, in tune with the topography of the landscape, tempered too a level relationship between privacy and group living.

The Sydney Opera House

Heading to Sydney for the Opera House commission was another opportunity for travel: ‘It was an adventure for the whole family,’ says Lin Utzon. ‘Our parents gave us a fantastic trip to Australia, stopping in different places – the Bahamas, Florida – we drove through the States seeing different architecture – and then we arrived in Sydney.’

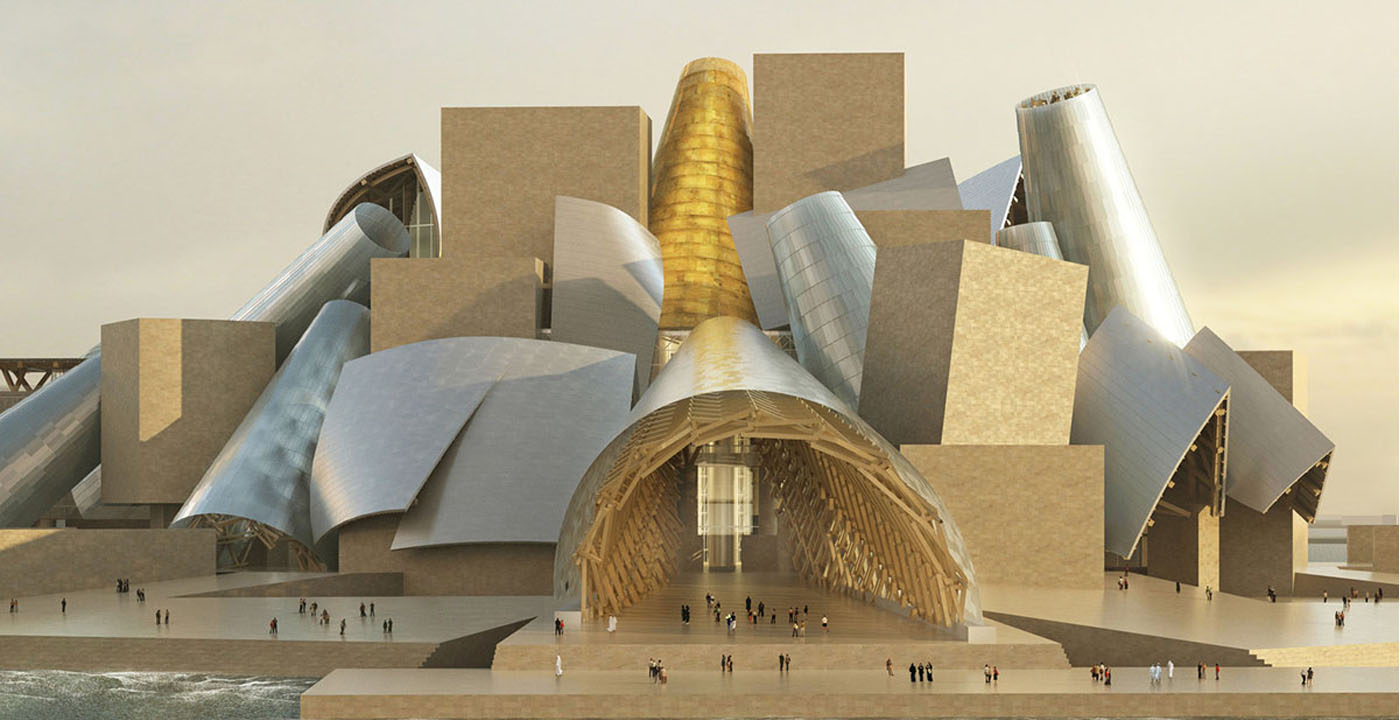

The exhibition places importance on the anticent platform temples of Mexico, an influence for the design of the Sydney Opera House and its strong base from which the iconic sails were placed. Nørskov Eriksen describes this moment as a turning point, and how it became clear that due to his travels and continued architectural observation, his work evolved into an accumulative combination of archetypes, a unique and personal style that made his work so distinct. ‘In the beginning, Utzon was very much interested in variation – how buildings could adapt to different contexts, different times, cultures, landscapes; and then eventually he became more and more influenced by this idea of permanence – that there are certain things in architecture that stay the same. At one point he talks about it as a seed that architecture has an innermost being, so that no matter where the seed is planted or at what time, it has a core substances,’ says Eriksen.

The Sydney Opera House, model and ephemera displayed in the exhibition at the Utzon Center in Aalborg, Denmark

‘He was very interested in the platform and these floating roofs as a way of installing a more existential dimension to architecture. For him it’s not just how the building operates on a daily basis, it’s about the relationship of man to the surroundings he is given.’ Utzon acheived this through other techniques, such as progression from the ‘cave’ to the ‘courtyard’, working with windows and capturing the horizon.

A wooden model of the Sydney Opera house on display, of which Utzon made 10 for each board member of the Sydney Opera House committee, belongs to Utzon’s son, Jan, also an architect. It’s one of the few pieces that he retained for himself instead of placing it in the Utzon Archive. For him, each of Utzon’s buildings have a human quality, no matter on what scale: ‘I feel walking through my father’s buildings there is a sense that you belong here – I can stay here. It’s not strange, or made of steel or granite, or a building where you say “its very interesting, but I would like to go home now”. The way the light comes in and the are materials chosen – he would always endevaour to create something with a human scale.’

From Sydney to Aalborg

The Utzon Center in Aalborg holds many similarities with the Sydney Opera House – from its waterfront location that changed the urban focus of the whole city, to its triangular peaks that add new shapes into its context. The centre accomodates working studios for architecture students from the local university and an experimental gallery space filled with heaps of lego bricks for building, constructed models and a full-sized boat parked for teaching students and visitors about timber constructuon, which Utzon saw as key to understanding architecture. From the pebbled courtyard, to the corridor galleries with interactive screens and the auditorium that eclipses views of the water, industrial horizon and sky – it offers opportunity for education, leisure and architectural appreciation.

‘The Opera House did on a different scale what this building [the Utzon Center] did to Aalborg’, says Lin Utzon. ‘At night time, when the full moon is reflected on the building and the water is smooth like glass, you become so aware of everything. It has that significance on all the surroundings to make that effect – and to make Aalborg a better place to live.’

Take a look at Jørn Utzon’s greatest architectural hits here

The Utzon Center in Aalborg, Utzon’s last piece of architecture.

Installation of the Horisont exhibition at the Utzon Center

INFORMATION

‘Horisont’ runs until 21 October 2018 as part of the ‘Utzon 100’ programme. For more information visit the Utzon Center website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expect

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expectFrom this season’s roster of Pitti Uomo guest designers to Jonathan Anderson’s sophomore men’s collection at Dior – as well as Véronique Nichanian’s Hermès swansong – everything to look out for at Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026

-

The international design fairs shaping 2026

The international design fairs shaping 2026Passports at the ready as Wallpaper* maps out the year’s best design fairs, from established fixtures to new arrivals.

-

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026With major new institutions gearing up to open their doors, it is set to be a big year in the art world. Here is what to look out for

-

A Dutch visitor centre echoes the ‘rising and turning’ of the Wadden Sea

A Dutch visitor centre echoes the ‘rising and turning’ of the Wadden SeaThe second instalment in Dorte Mandrup’s Wadden Sea trilogy, this visitor centre and scientific hub draws inspiration from the endless cycle of the tide

-

Rains Amsterdam is slick and cocooning – a ‘store of the future’

Rains Amsterdam is slick and cocooning – a ‘store of the future’Danish lifestyle brand Rains opens its first Amsterdam flagship, marking its refined approach with a fresh flagship interior designed by Stamuli

-

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architecture

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architectureWe visit three Danish modernist houses with writer, curator and architecture historian Adam Štěch, a delve into lower-profile examples of the country’s rich 20th-century legacy

-

Is slowing down the answer to our ecological challenges? Copenhagen Architecture Biennial 2025 thinks so

Is slowing down the answer to our ecological challenges? Copenhagen Architecture Biennial 2025 thinks soCopenhagen’s inaugural Architecture Biennial, themed 'Slow Down', is open to visitors, discussing the world's ‘Great Acceleration’

-

This cathedral-like health centre in Copenhagen aims to boost wellbeing, empowering its users

This cathedral-like health centre in Copenhagen aims to boost wellbeing, empowering its usersDanish studio Dorte Mandrup's new Centre for Health in Copenhagen is a new phase in the evolution of Dem Gamles By, a historic care-focused district

-

This tiny church in Denmark is a fresh take on sacred space

This tiny church in Denmark is a fresh take on sacred spaceTiny Church Tolvkanten by Julius Nielsen and Dinesen unifies tradition with modernity in its raw and simple design, demonstrating how the church can remain relevant today

-

‘Stone, timber, silence, wind’: welcome to SMK Thy, the National Gallery of Denmark expansion

‘Stone, timber, silence, wind’: welcome to SMK Thy, the National Gallery of Denmark expansionA new branch of SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark, opens in a tiny hamlet in the northern part of Jutland; welcome to architecture studio Reiulf Ramstad's masterful redesign of a neglected complex of agricultural buildings into a world-class – and beautifully local – art hub

-

Discover Bjarke Ingels, a modern starchitect of 'pragmatic utopian architecture'

Discover Bjarke Ingels, a modern starchitect of 'pragmatic utopian architecture'Discover the work of Bjarke Ingels, a modern-day icon and 'the embodiment of the second generation of global starchitects' – this is our ultimate guide to his work