Houses of the Sundown Sea: The architectural vision of Harry Gesner

Los Angeles natives refashion the world from one of two perspectives: that of the relentless romantic or the cynic. The title of 86-year-old architect Harry Gesner's first monograph establishes him firmly in the former group.

Gesner, who is still working (and surfing) today, represents one of the most glamorous stories of the schismatic strain of Modernism that has quietly studded the state of California with masterpieces by the likes of contemporaries John Lautner and Mickey Muennig.

The monograph's admiring and lightly gossipy text by Lisa Germany depicts a maverick mind and a thoroughly heterodox 60-year oeuvre. Though Abrams' prosaic design of the book, itself, in no way reflects the originality of Gesner's work, it includes drawings and plans and new and archival imagery that elucidate the architect's rich structural, formal and material creativity.

Before he started his own practice at 25, Gesner's architectural education consisted of soldier's-eye views of WWII European architecture, a class audited at Yale where he turned down an invitation from Frank Lloyd Wright to visit Taliesen, and a year-long construction apprenticeship.

His second house declared his heresy: made from energy-efficient, quake-resistant, unplastered adobe brick, the façade rose, at a 30-degree angle to form toothy clerestory windows and a cantilevering, triangular fireplace. His break came in 1959 with one of the west coast's first A-frame houses featuring a black concrete floor inlaid with semiprecious minerals.

Many of Gesner's clients sought him out because he could build on limited budgets and 'unbuildable' sites, and because that impossibility - and the views - shaped what he built. He made houses that hang like a bridge between canyon walls; 'hang 10' over the lip of a cliff; or that could only be reached by funiculars. They are scaled like fish or rigged by Norwegian shipbuilders; he sketched his Wave house in grease pencil from beyond the surf line on a 12-foot balsa board.

Gesner's living and dining rooms were sunken, his kitchens and wet bars were raised, his staircases spiraled. Fireplaces, like his early pools, floor plans, windows and decks were often triangular; only mid-career did he 'discover roundness'.

From the 1970s onward, the patchwork combinations of (laudably upcycled) materials suggests that Gesner lost control of the teeming and eclectic ideas that he packaged with such coherence early on. Nonetheless, Gesner's work begs the question: Why hasn't unorthodox architecture gone forth and multiplied?

Gesner in 1965 at the peak of his career, with a scroll of plans for the Scantlin house tucked under his arm and the skeleton of the house behind him

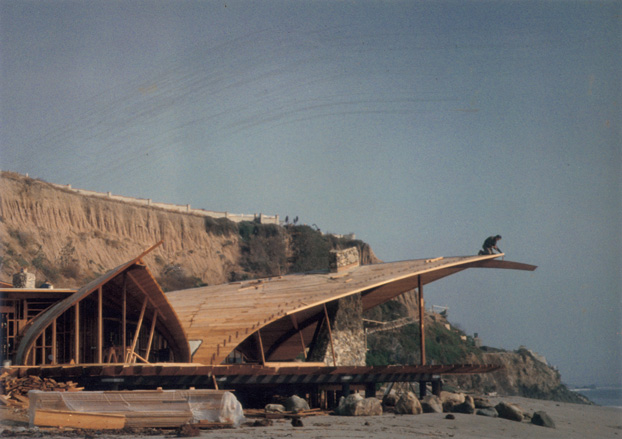

The framework of the Cooper Wave house, completed in 1959, with skeletal vaults beginning to take shape

The Cooper Wave house under construction, with Gesner at work at the tip of the vault. Before he conceived the house, Gesner spent days surfing the waves in front of the plot and contemplating the design. Finally, he says, 'I paddled out through the break, turned the board to the beach, and sketched the Wave house on the face of the board'

Gesner designed the wave-like copper roof of the house in such a way that hidden, self-attaching tabs on each shingle would fit together as tightly as fish scales, and their texture and eventual patina would have subtle seaside connotations

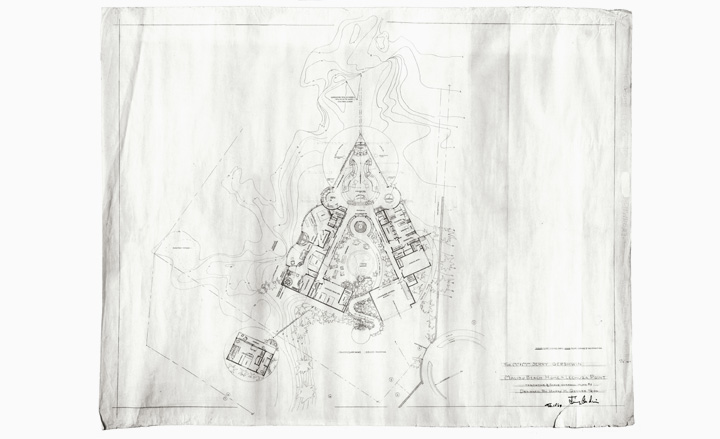

Gesner's proposal for a beachfront site in the Malibu Colony, 1966. Because the site was on a spit of land pointing out toward the ocean, Gesner was inspired to design a house fashioned after a boat at sea

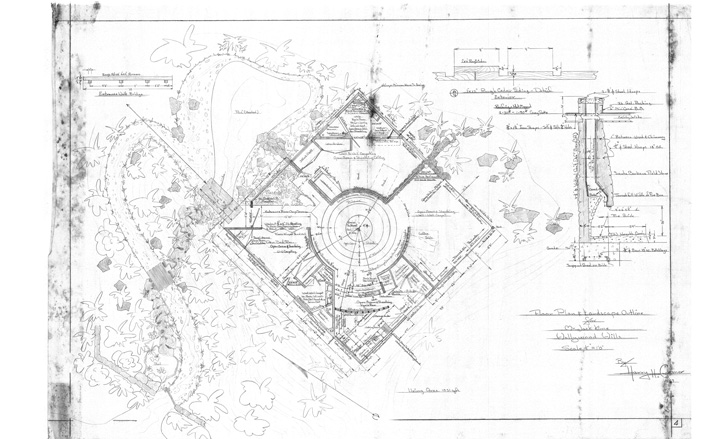

Floor plan of the Hunt/Kime house, LA. How do you tackle the curse of a perfectly flat site?, the architect asked. 'You design a round house inside of it and use the straight exterior walls as the basic structural elements, both vertical and horizontal.' Rain water drained into a central koi pond and a swimming pool surrounding three sides of the house

In Gesner's Sandcastle house, the stucco hood above the living room fireplace acted as a touchstone for the idea of the sandcastle as house

The double-height arch in the Robert Jones house living room works with the foundation of caissons to brace the house against the incoming waves, while giving the house its seagoing aspect

In the Aliberti Eagle's Watch house, Gesner brought glass and beams together to forge connections between house and sea

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Shonquis Moreno has served as an editor for Frame, Surface and Dwell magazines and, as a long-time freelancer, contributed to publications that include T The New York Times Style Magazine, Kinfolk, and American Craft. Following years living in New York City and Istanbul, she is currently based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

-

From dress to tool watches, discover chic red dials

From dress to tool watches, discover chic red dialsWatch brands from Cartier to Audemars Piguet are embracing a vibrant red dial. Here are the ones that have caught our eye.

-

Behind a contemporary veil, this Kyoto house has tradition at its core

Behind a contemporary veil, this Kyoto house has tradition at its coreDesigned by Apollo Architects & Associates, a Kyoto house in Uji City is split into a series of courtyards, adding a sense of wellbeing to its residential environment

-

EV maker Rivian creates its first Concept Experience in New York’s Meatpacking District

EV maker Rivian creates its first Concept Experience in New York’s Meatpacking DistrictUnder the High Line, in the heart of one of New York’s most famous neighbourhoods is the Rivian Concept Experience, a showroom designed to surprise and delight both long-term aficionados and total newcomers to the brand

-

Ukrainian Modernism: a timely but bittersweet survey of the country’s best modern buildings

Ukrainian Modernism: a timely but bittersweet survey of the country’s best modern buildingsNew book ‘Ukrainian Modernism’ captures the country's vanishing modernist architecture, besieged by bombs, big business and the desire for a break with the past

-

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yoursJean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

-

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, UzbekistanThe legacy of modernist architecture in Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent, is explored through research, a new publication, and the country's upcoming pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; here, we take a tour of its riches

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

-

How Le Corbusier defined modernism

How Le Corbusier defined modernismLe Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

-

How to protect our modernist legacy

How to protect our modernist legacyWe explore the legacy of modernism as a series of midcentury gems thrive, keeping the vision alive and adapting to the future

-

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st Century

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st CenturyThanks to a sensitive redesign by Studio Hagen Hall, this midcentury gem in Hampstead is now a sustainable powerhouse.

-

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tall

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tallMuseu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP) expands with a project named after Pietro Maria Bardi (the institution's first director), designed by Metro Architects