Japanese architecture, craft and Modernism meet in Philadelphia

A new exhibition in Philadelphia explores the relationship between Shofuso House, a piece of 17th century-style Japanese architecture located in the city's West Fairmount Park, and Modernism through the connections between architect Junzo Yoshimura, woodworker George Nakashima, designer Noémi Pernessin Raymond and architect Antonin Raymond

Walk past Philadelphia’s Museum of Modern Art, past the zoo and deeper into West Fairmount Park’s blanket of woods and you will eventually happen upon a traditional piece of 17th century Japanese architecture.

Shofuso Japanese House and Gardens, a shoin house (a type of traditional Japanese residential architecture) subtly infused with modernist details, was built in Japan in 1953 by the Tokyo-based architect Junzo Yoshimura, before being shipped to America’s East Coast for a 1954 outdoor exhibition titled ‘The House in the Museum Garden' at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Shufuso, which is now the setting for an exhibition titled ‘Shofuso and Modernism: Mid-Century Collaboration between Japan and Philadelphia', came into existence, then, only a few years after America had decimated two Japanese cities via the use of atomic bombs after months of sustained firebombing from the air.

The house, as it stands today, embodies the abilities of both nations to foster, in the years directly following the war, and as Japan began to rebuild itself from under the rubble, a new tradition of mutual respect – not to mention an enduring cultural fascination and cross-pollination.

Shofuso, which moved to Philly in 1957, is an expression of Yoshimura’s interpretations of the Japanese classical shoin-zukuri style of architecture. ‘If you want to study Japanese architecture, don’t study the sukiya style,' he once said. ‘Begin by studying the shoin style.'

Yet Yoshimura spent his career at the heel of one of Europe’s great architects of the time, learning how to fuse shoin principles with rationalist and modernist thinking. Shofuso, then, is the child of a historic connection between Eastern and Western cultures, and a hinge between nationalist tradition and internationalist modernity.

But the exhibition on show in Shofuso today, and, indeed, the architecture of the building itself, also tells a very intimate, very personal story between Japanese, Japanese-American and European architects.

The show is curated by Yuka Yokoyama and William Whitaker. Yokoyama says: ‘When I got a job at Shufuso about a year and half ago, I started researching the house in which I worked. I didn’t realise the connections and friendships between Yoshimura, Nakashima and the Raymonds. Shofuso came to represent these connections. You can see this friendship in the house’s design.'

‘For more than fifty years, Shofuso has been a centre for Japanese culture and its interpretation as understood through this house and garden,' says Whitaker. ‘But it has this complicated history. It’s a building built in the modern era, but, for most people who visit here, they see what appears to be a 17th century Japanese house. But there’s a lot more to it; the stories of the people who made it, the historical times on which it was created. It encompasses the vicious times of war, and the inhumane experiences of Japanese-Americans in this country. Whilst it’s a place of calm, serenity, life and joy, the project hopes to open a dialogue by opening up an interpretation of this circle of artists.'

The Czech-born architect Antonin Raymond and his French wife, Noémi Pernessin Raymond, first moved to Tokyo in the late 1910s as employees of Frank Lloyd Wright. Together, they worked on Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. But Raymond became frustrated with the experience and split with Wright to set up, in February of 1921, the American Architectural and Engineering Company in Tokyo with Leon Whittaker Slack.

In December 1928, while a student at Tokyo's Fine Arts College, Yoshimura began part-time work at Raymond's office, becoming full-time after he graduated in 1931. Through the teachings of Wright, and through their own encounter with and study of Japanese culture, the Raymonds were able to integrate the theories of modernism with classical Japanese architectural principles.

This fed down into the processes of their precocious young assistant Yoshimura. As such, a perfect harmony was formed between traditional Japanese construction methods and the emerging canons of modern Western design.

This storied journey of Yoshimura, as well as his Japanese-American contemporary George Nakashima, from lowly employees to co-collaborators to, eventually, cohabiters of the Raymond’s home, serve as the nucleus around which the exhibition exists.

In Pennsylvania, on the rural outskirts of Philadelphia, lies a bucolic farming town on the banks of the Delaware River called New Hope. In the 1930s, the town became the home of Antonin and Noémi Raymond, and then Yoshimura too, who purchased the land next door to the Raymond's farm. New Hope also became home to George Nakashima, a Japanese-American who was born in Washington in 1905 to Japanese parents and, after living a Bohemian life in Europe, came to work for Raymond as an architect in Tokyo.

At the onset of the Second World War in 1940, Nakashima returned to America before, in March 1942, becoming forcibly interned by the American government. He was sent to Camp Minidoka in Hunt, Idaho. There he met Gentaro Hikogawa, a man trained in traditional Japanese carpentry, who taught Nakashima to carve and create with wood using traditional Japanese hand tools and joinery techniques.

In late 1943, the Raymonds sponsored Nakashima, rescuing him from the camp and taking him home to New Hope. In a studio on the farm, Nakashima put his new skills to use, turning local trees into stunning furniture pieces that now fill Shofuso’s rooms. Beautifully simple as they appear to be, they are creations born of a profound sense of optimism; that what binds us is always greater than what pulls us apart.

INFORMATION

Shofuso And Modernism: Mid-Century Collaboration Between Japan and Philadelphia, until November 29 2020

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

Form... and flavour? The best design-led restaurant debuts of 2025

Form... and flavour? The best design-led restaurant debuts of 2025A Wallpaper* edit of the restaurant interiors that shaped how we ate, gathered and lingered this year

-

The rising style stars of 2026: Zane Li, fashion’s new minimalist

The rising style stars of 2026: Zane Li, fashion’s new minimalistAs part of the January 2026 Next Generation issue of Wallpaper*, we meet fashion’s next generation. First up, Zane Li, whose New York-based label LII is marrying minimalism with architectural construction and a vivid use of colour

-

The work of Salù Iwadi Studio reclaims African perspectives with a global outlook

The work of Salù Iwadi Studio reclaims African perspectives with a global outlookWallpaper* Future Icons: based between Lagos and Dakar, Toluwalase Rufai and Sandia Nassila of Salù Iwadi Studio are inspired by the improvisational nature of African contemporary design

-

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of Japan

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of JapanDesigned by MIDW, a house nestled in the south-west Tokyo district features contrasting spaces united by the calming rhythm of structural timber beams

-

Take a tour of the 'architectural kingdom' of Japan

Take a tour of the 'architectural kingdom' of JapanJapan's Seto Inland Sea offers some of the finest architecture in the country – we tour its rich selection of contemporary buildings by some of the industry's biggest names

-

Matsuya Ginza lounge is a glossy haven at Tokyo’s century-old department store

Matsuya Ginza lounge is a glossy haven at Tokyo’s century-old department storeA new VIP lounge inside Tokyo’s Matsuya Ginza department store, designed by I-IN, balances modernity and elegance

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthThis September, Wallpaper highlighted a striking mix of architecture – from iconic modernist homes newly up for sale to the dramatic transformation of a crumbling Scottish cottage. These are the projects that caught our eye

-

Utopian, modular, futuristic: was Japanese Metabolism architecture's raddest movement?

Utopian, modular, futuristic: was Japanese Metabolism architecture's raddest movement?We take a deep dive into Japanese Metabolism, the pioneering and relatively short-lived 20th-century architecture movement with a worldwide impact; explore our ultimate guide

-

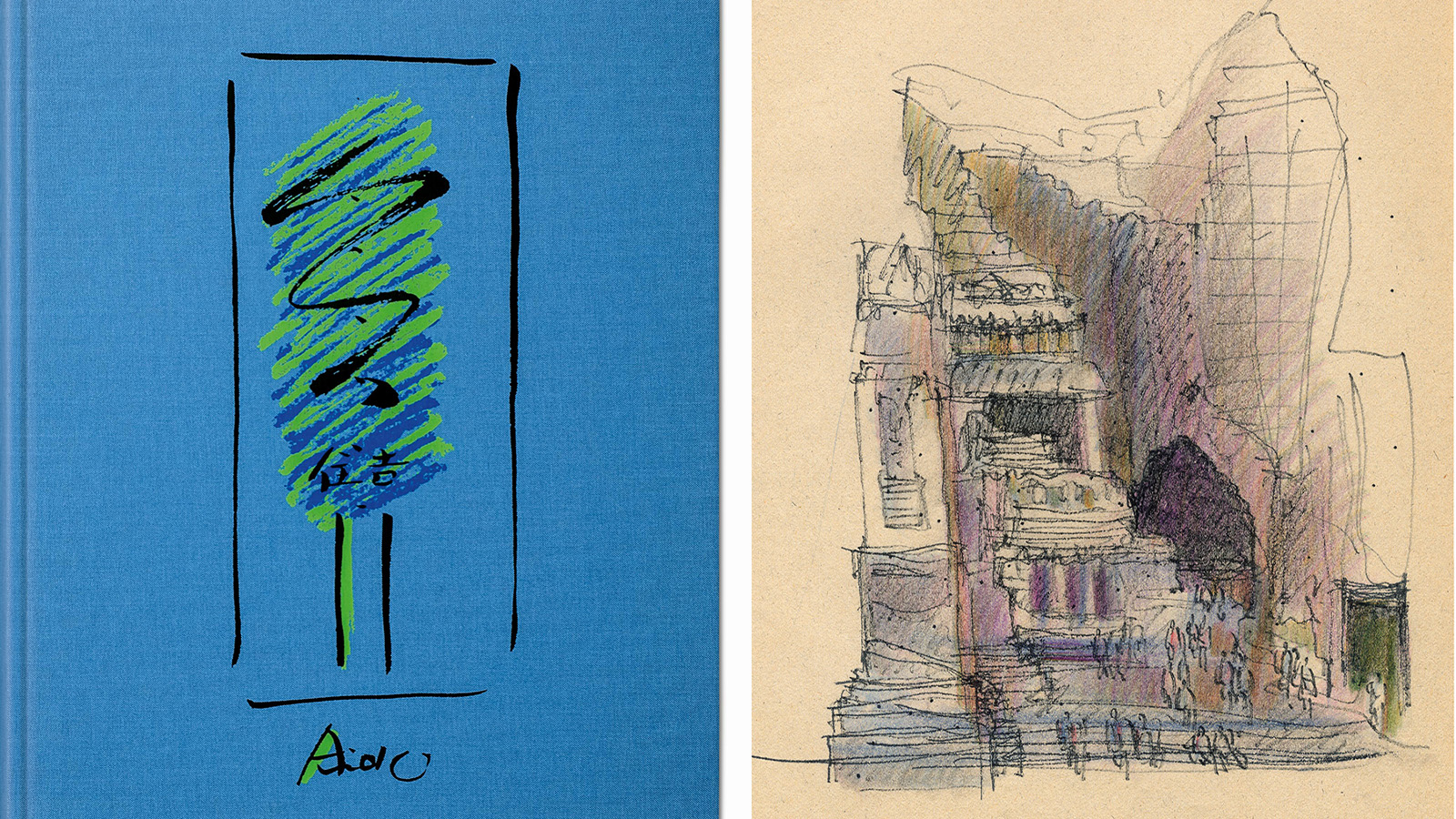

A new Tadao Ando monograph unveils the creative process guiding the architect's practice

A new Tadao Ando monograph unveils the creative process guiding the architect's practiceNew monograph ‘Tadao Ando. Sketches, Drawings, and Architecture’ by Taschen charts decades of creative work by the Japanese modernist master

-

A Tokyo home’s mysterious, brutalist façade hides a secret urban retreat

A Tokyo home’s mysterious, brutalist façade hides a secret urban retreatDesigned by Apollo Architects, Tokyo home Stealth House evokes the feeling of a secluded resort, packaged up neatly into a private residence

-

Landscape architect Taichi Saito: ‘I hope to create gentle landscapes that allow people’s hearts to feel at ease’

Landscape architect Taichi Saito: ‘I hope to create gentle landscapes that allow people’s hearts to feel at ease’We meet Taichi Saito and his 'gentle' landscapes, as the Japanese designer discusses his desire for a 'deep and meaningful' connection between humans and the natural world