Museums to come: Jean Nouvel and Claude Parent at Azzedine Alaïa

The moment a new museum opens, it goes from being an ambitious concept to a multi-purpose institution rooted in time and space. But what about the museums that are conceived but never achieved? To what degree do they exist as architectural works, and what is their enduring value?

These are among the questions that surface in a new exhibition, 'Musées à Venir' ('Museums to Come') at Azzedine Alaïa’s gallery space in the Marais. If the premise seems philosophically open-ended, this particular show proves as precise as the master designer’s tailoring, in part because just two architects are represented: Jean Nouvel and Claude Parent. A generation apart, the former worked under the latter in the late 1960s, and they have intersected each other’s lives ever since. In fact, it was over lunch chez Alaïa in June 2014, that the idea took shape.

As academic and gallery consultant Donatien Grau suggests, the juxtaposition exists as a conversation that can be interpreted on several levels: theoretically, personally, aesthetically. Four works from each are featured, including their separate proposals for the Plateau Beaubourg, 1971 – better known today as the Centre Pompidou. And yet, the architects’ projects are grouped separately on alternating walls versus side-by-side, maintaining deliberate distance like a show of respect.

'They are two very senior architects and on the one hand, it would have been too obvious,' Grau says, of opting against pairing the presentation. 'Both Jean Nouvel and Claude Parent believe deeply in the idea of intelligence – getting you to do a little bit of work. And what is a conversation might have appeared to be a confrontation.'

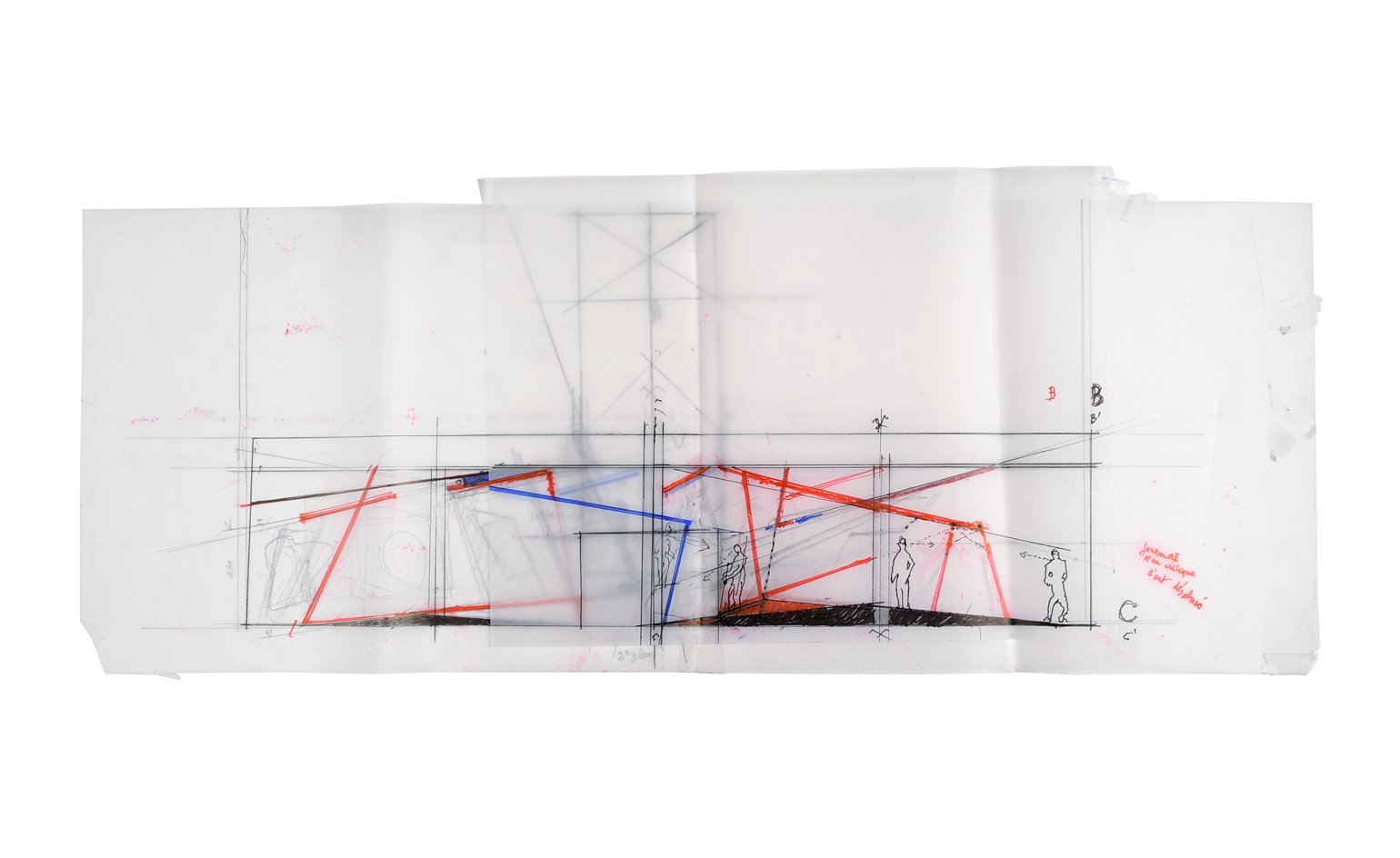

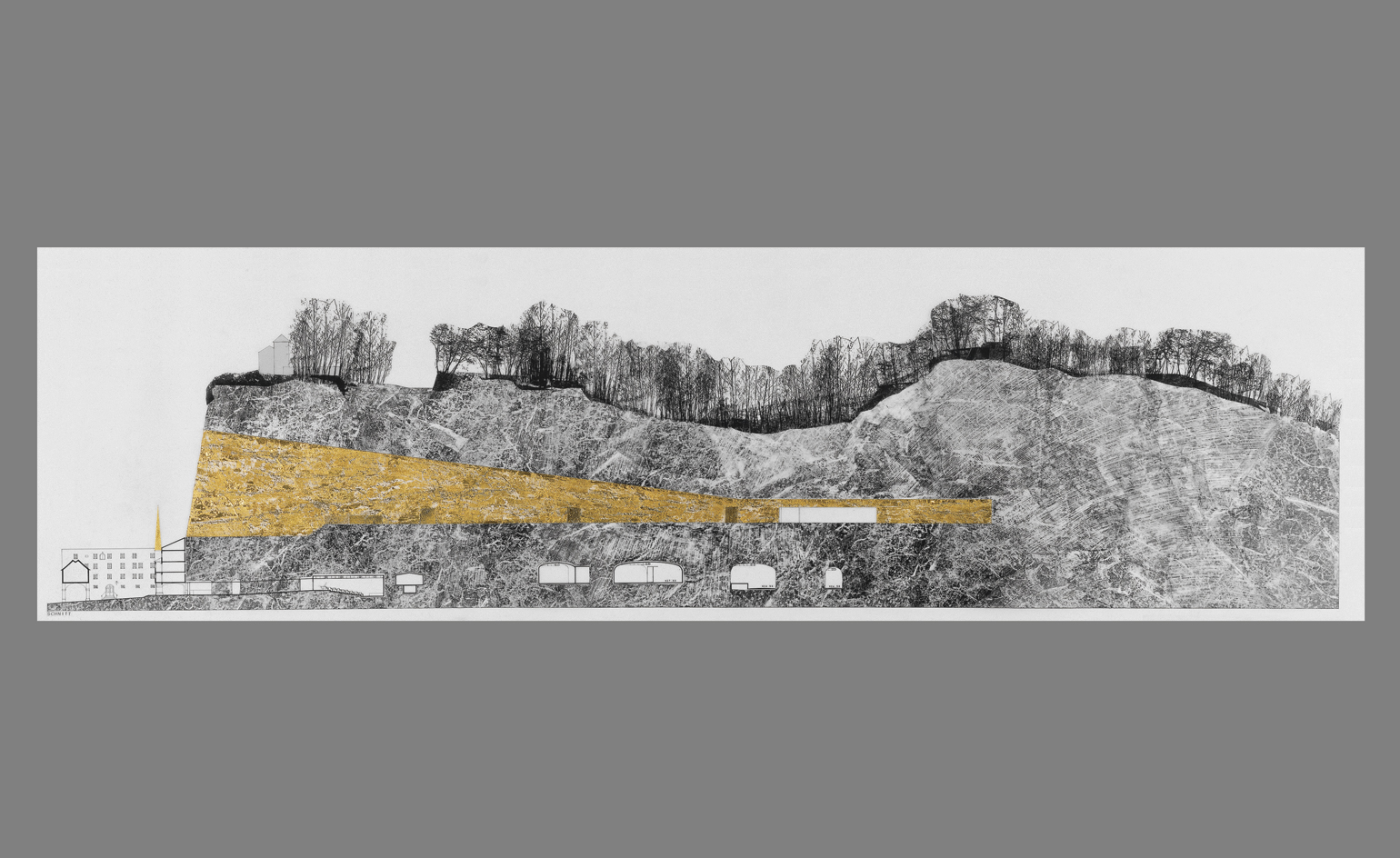

Still, comparison is inevitable, principally as a function of methodology. Parent’s dynamic drawings for the Nouveau Musée, an unpublished work featured for the first time, testify to the enormous challenge of communicating spatial criteria and visitor flow in two dimensions. Nouvel’s plans for the Musée Lascaux-IV , 2012, and the Guggenheim in Guadalajara, 2005, benefit from computer-assisted design and project a sharper sense of orientation. Where Parent’s text is clipped and aphoristic – 'In the world today, we cannot forget color, just as we cannot forget the black of night and the grey sky' – Nouvel takes an explanatory, narrative approach.

For even more perspective, the book accompanying the exhibition includes works contributed by Marc Newson, Anish Kapoor, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Adel Abdessemed and others—each partnered up to a project to underscore how Parent and Nouvel’s influence prompt new points of departure.

On the evening of the vernissage, shortly before the arrival of Parent (now 92), Renzo Piano and French culture minister Fleur Pellerin, Nouvel admits that these projects never lose their significance. They serve as the missing links between the realised achievements, a vision that nonetheless responds to a challenge. 'We can consider that the conditions of these projects enlighten perhaps the things that will often happen after,' he tells Wallpaper*. Which is to stay, an unrealised state isn’t a failed state. Rather, these are museums that become timeless, says Nouvel, 'out of necessity'.

A new show at Paris’ Azzedine Alaïa asks to what degree museums conceieved but never built exist as architectural works, and what their enduring value is. It focuses on just the work of Parent and Nouvel. Pictured: Centre International de L’art Parietal Lascaux IV, by Jean Nouvel, 2012. Courtesy Ateliers Jean Nouvel

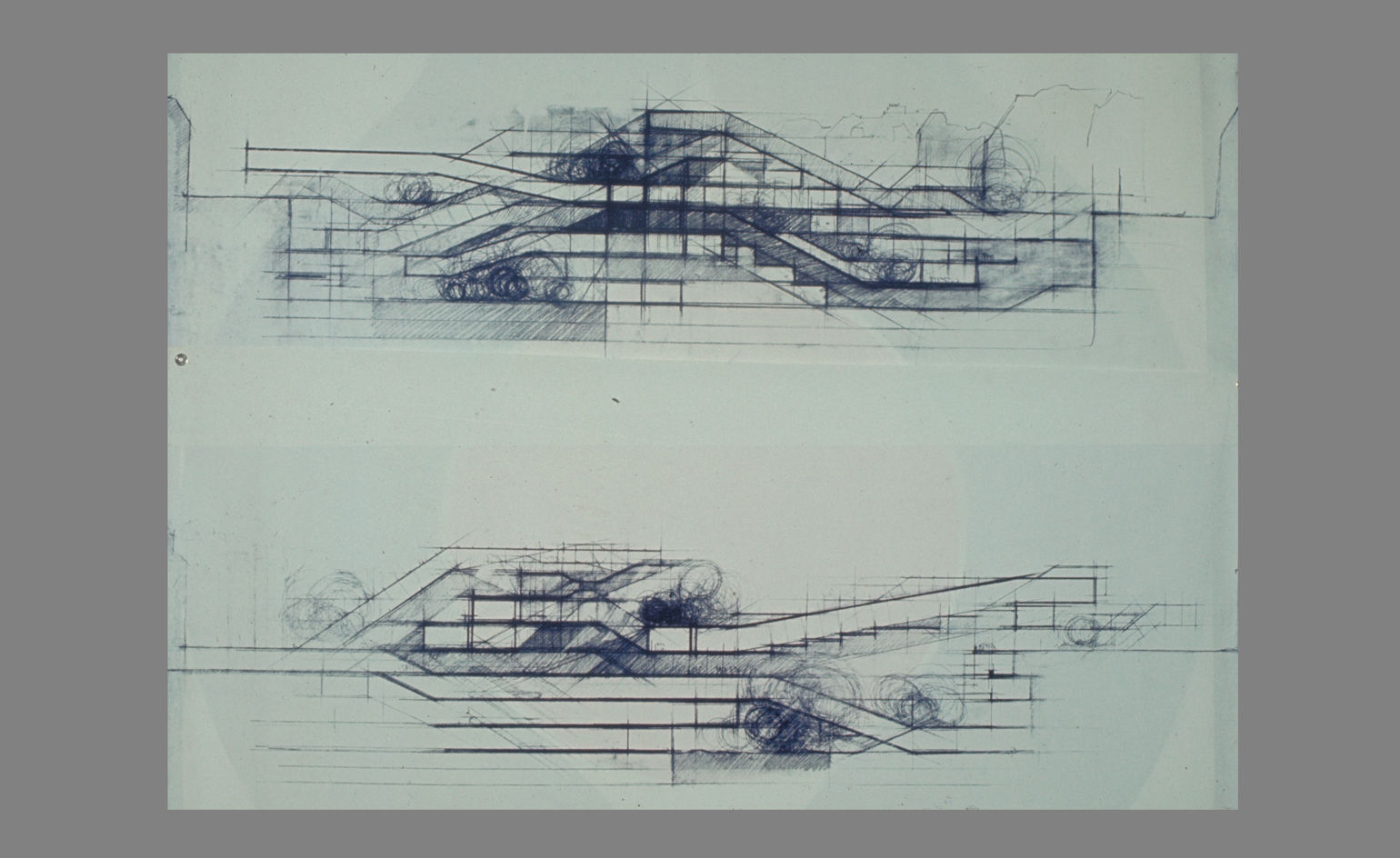

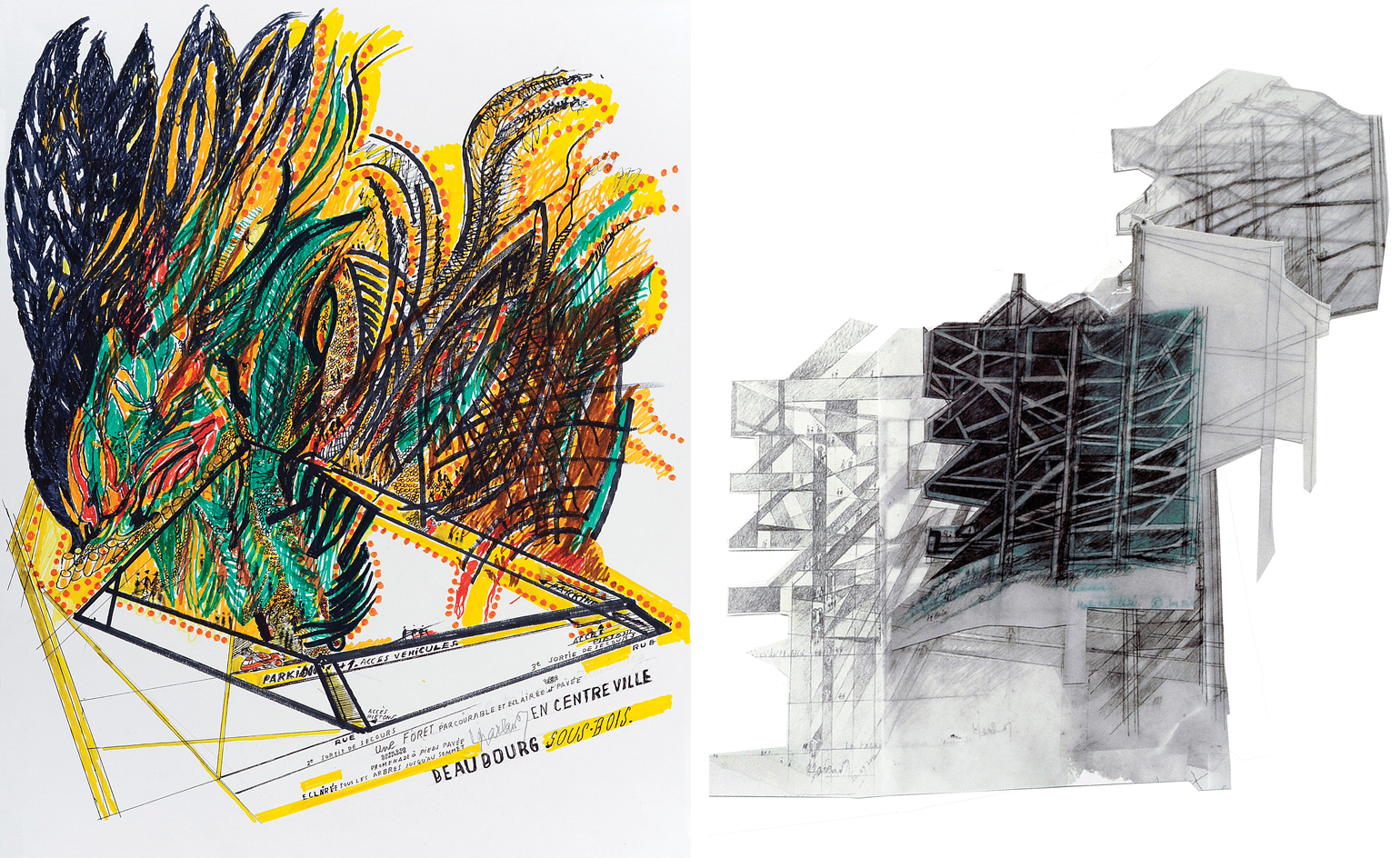

Four works from each are featured, including their separate proposals for the Plateau Beaubourg, 1971 – better known today as the Centre Pompidou. Pictured: Centre National d’Art et de Culture Plateau Beaubourg, by Jean Nouvel, 1971. Courtesy the architect, François Seigneur, Yann Lecoq

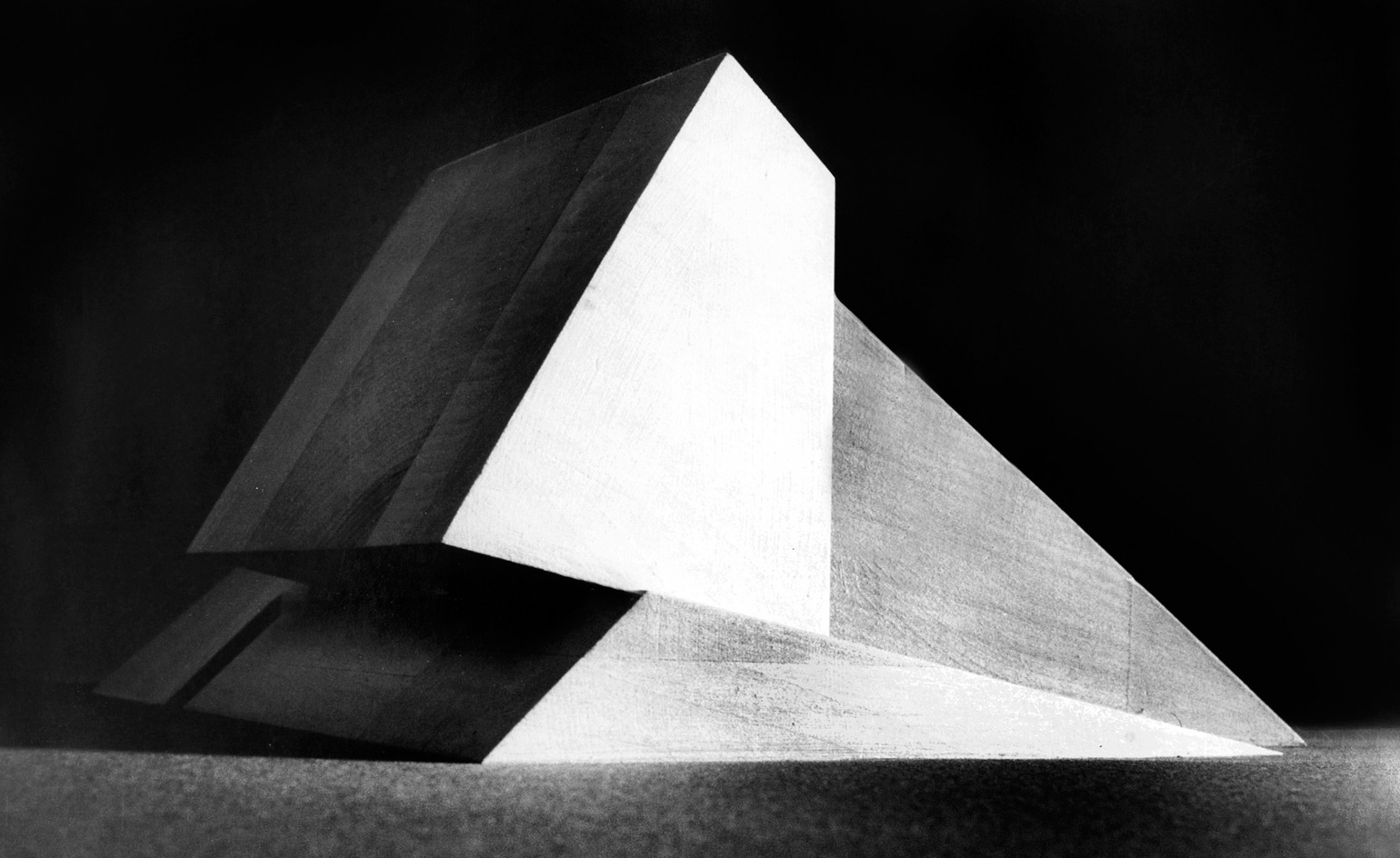

As academic and gallery consultant Donatien Grau suggests, the juxtaposition exists as a conversation that can be interpreted on several levels: theoretically, personally, aesthetically. Pictured: Le Halo de la Fleche, by Jean Nouvel, 1989. Courtesy the architect, Emmanuel Cattani & associés

Le Halo de la Fleche, by Jean Nouvel, 1989 Courtesy the architect, Emmanuel Cattani & associés

The architects’ projects are grouped separately on alternating walls versus side-by-side, maintaining deliberate distance like a show of respect. Pictured: Musée d’Art Moderne Oblique, by Claude Parent, 1972. Photography: Michel-Charles Gaffier. Courtesy Dennis Bouchard

Nouvel admits that these projects never lose their significance. They serve as the missing links between the realised achievements, a vision that nonetheless responds to a challenge. Pictured left: Projet de Plateau Beaubourg, by Claude Parent, 1971. Courtesy Dennis Bouchard. Right: Le Nouveau Musée, by Claude Parent, 2014–2015. Courtesy Dennis Bouchard

INFORMATION

'Musées a Venir' is on view until 28 February. The accompanying book is published jointly by Actes Sud and Association Azzedine Alaïa

ADDRESS

Azzedine Alaïa

18, rue de la Verrerie

75004 Paris

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Miami’s new Museum of Sex is a beacon of open discourse

Miami’s new Museum of Sex is a beacon of open discourseThe Miami outpost of the cult New York destination opened last year, and continues its legacy of presenting and celebrating human sexuality

By Anna Solomon

-

Royal College of Physicians Museum presents its archives in a glowing new light

Royal College of Physicians Museum presents its archives in a glowing new lightLondon photography exhibition ‘Unfamiliar’, at the Royal College of Physicians Museum (23 January – 28 July 2023), presents clinical tools as you’ve never seen them before

By Martha Elliott

-

Museum of Sex to open Miami outpost in spring 2023

Museum of Sex to open Miami outpost in spring 2023The Museum of Sex will expand with a new Miami outpost in spring 2023, housed in a former warehouse reimagined by Snøhetta and inaugurated with an exhibition by Hajime Sorayama

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Jenny Holzer curates Louise Bourgeois: ‘She was infinite’

Jenny Holzer curates Louise Bourgeois: ‘She was infinite’The inimitable work of Louise Bourgeois is seen through the eyes of Jenny Holzer in this potent meeting of minds at Kunstmuseum Basel

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

‘A Show About Nothing’: group exhibition in Hangzhou celebrates emptiness

‘A Show About Nothing’: group exhibition in Hangzhou celebrates emptinessThe inaugural exhibition at new Hangzhou cultural centre By Art Matters explores ‘nothingness’ through 30 local and international artists, including Maurizio Cattelan, Ghislaine Leung, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Liu Guoqiang and Yoko Ono

By Yoko Choy

-

Three days in Doha: art, sport, desert, heat

Three days in Doha: art, sport, desert, heatIn our three-day Doha diary, we record the fruits of Qatar’s cultural transformation, which involved Jeff Koons, a glass palace of books, and a desert sunset on Richard Serra

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Hong Kong’s M+ Museum to open with six thematic shows

Hong Kong’s M+ Museum to open with six thematic showsAsia’s first global museum of contemporary visual culture will open on 12 November in Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District, with six themed shows spanning art, design and architecture

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Maurizio Cattelan invites the who’s who of culture to read bedtime stories

Maurizio Cattelan invites the who’s who of culture to read bedtime storiesThe subversive Italian artist has recruited the likes of Iggy Pop, Takashi Murakami and Joan Jonas to read bedtime stories in a new digital project for the New Museum

By Pei-Ru Keh