Junya Ishigami’s architecture aims high and digs deep at Fondation Cartier in Paris

The Tokyo studio of Japanese architect Junya Ishigami is in a state of controlled chaos. A number of large project models are scattered across the white workspace, with even more packed in cardboard boxes and stacked on one side. A corner has been partly cordoned off as an impromptu paint booth with a thin plastic curtain hanging from the ceiling. Here, a couple of the studio’s 20 or so staff are working on finalising a large styrofoam mould of one of Ishigami’s most recent projects, a poured concrete house and restaurant scheme in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan.

Rather unexpectedly, Ishigami’s studio is located underneath a large pet supply store. Both the walls (a mix of cement blocks and bricks) and the exposed ceiling are painted white. There are no windows, but neat rows of fluorescent tubes flood the space with a remarkably pleasant light. Right in the middle, a rough opening has been drilled through the floor, and a steel staircase leads down to a storage room packed with discarded bits of models and cardboard boxes.

There is also access to a large roof terrace (with the Tokyo Tower as a beautiful backdrop), where 1:1 plans of several projects are plotted on the oor using masking tape. ‘As everything we do is always completely new, it’s very helpful to make these plans to get an understanding of a given space,’ explains Ishigami, who worked at SANAA before founding his practice in 2004.

A couple of work desks with computers are squeezed together at one end of the studio, but it is the many large models that take up the bulk of the space. They are being given a careful clean-up before being shipped to France for a big exhibition of Ishigami’s work at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, opening this spring. It’s the first time the foundation has devoted a full exhibition to an architect. This also places Ishigami, the winner of the Golden Lion award at the 2010 Venice Biennale of Architecture, in the company of fellow countrymen such as Takashi Murakami, Isamu Noguchi and Hiroshi Sugimoto, who have all had their work shown there in the past.

Junya Ishigami’s House/Restaurant project under construction in Yamaguchi, Honshu.

According to director of exhibitions Isabelle Gaudefroy, Ishigami is still fairly unknown in the French capital. ‘Junya is known by architecture lovers but not by a broader audience,’ she says. ‘We think this will be a first discovery for most of the audience.’ Gaudefroy has been keeping an eye on the architect since his spectacular Cuboid Balloon (an oversized helium-filled shining monolith) at the ‘Space for Your Future’ exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, in 2007 and offered him a solo show two years ago.

The exhibition will show 20 of Ishigami’s past, current and future projects through large-scale models, accompanied by drawings and film. It’s hard to categorise Ishigami’s extremely varied works. Relatively few of them are what you could describe as ‘conventional’ buildings, and few are permanent structures. There is a cube-shaped house filled with greenery for a young couple in Tokyo; a kindergarten with cloud-shaped walls in Atsugi; and a stunning open-plan, glass-wrapped workshop at the Kanagawa Institute of Technology. But what he is perhaps best known for so far is his work on pavilions, installations and temporary exhibitions.

For Ishigami, though, all of his projects are pure architecture. ‘I don’t think it is so important to ask whether something is architecture or not,’ he says, adding that he sees even models as important creations in their own right: ‘Architects use models to imagine spaces and, in that sense, I believe the models themselves should be considered architecture.’ The studio makes regular use of models in its design development, but there is no set formula for the process. ‘Sometimes I start with a drawing, sometimes with a model. In the case of the House/Restaurant in Yamaguchi, it was the construction process that was the starting point.’

A concrete model of Junya Ishigami’s House/Restaurant.

The construction of the Yamaguchi project is, to put it mildly, rather unique. The client requested a cave-like space where he could use part of the building as a restaurant and part of it as his private residence. Ishigami came up with the idea to create a series of holes in the ground, pour concrete into these and then dig out the spaces between the resulting concrete stalactites – and voilà! What you end up with is an almost natural-looking cave that only needs to be tted with carefully sized windows and doors in order to create an enticing interior.

The original idea was to clean the poured concrete columns, but after they started di ing around these, Ishigami was attracted to the earthy quality of the surface, the result of soil sticking to the poured concrete. ‘I thought, this is very similar to traditional Japanese earthen walls, why don’t we keep it like this,’ he recalls.

Ishigami likes these small accidents and unexpected elements of the trade; the architect also likes to find inspiration in the natural world and the existing landscape, assembling disparate found objects into new compositions that add meaning and worth to often mundane things. This is apparent in his project in Akita, for which he has designed homes for the elderly made up of parts of homes scheduled for demolition, sourced from across the country; or his large Art Biotop garden project in Nasu, where he carefully selected and replanted 300 trees from an adjacent plot.

Ishigami is passionate about his work and is sure that a change is coming that will liberate architecture from ‘just’ being about designing and constructing buildings. ‘I don’t think about style in my architecture,’ he says. ‘I want to free myself and propose what is right for a certain project at a certain location.’ There is a true curiosity and passion for experimentation in Ishigami’s work, and with upcoming projects including a floating cloud-shaped House of Peace in Denmark, a monumental silver arch in Sydney, and further commissions in Japan and China, the next couple of years might just set him and his architecture free.

As originally featured in the April 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*229)

The house/restaurant in Yamaguchi under construction

Studies of the pillars

Ishigami’s studio (left) and the construction site, once the earth had been dug from around the concrete stalactites (right)

INFORMATION

‘Junya Ishigami: Freeing Architecture’ runs from 30 March - 10 June 2018. For more information, visit the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris website and the Junya Ishigami + Associates website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Originally from Denmark, Jens H. Jensen has been calling Japan his home for almost two decades. Since 2014 he has worked with Wallpaper* as the Japan Editor. His main interests are architecture, crafts and design. Besides writing and editing, he consults numerous business in Japan and beyond and designs and build retail, residential and moving (read: vans) interiors.

-

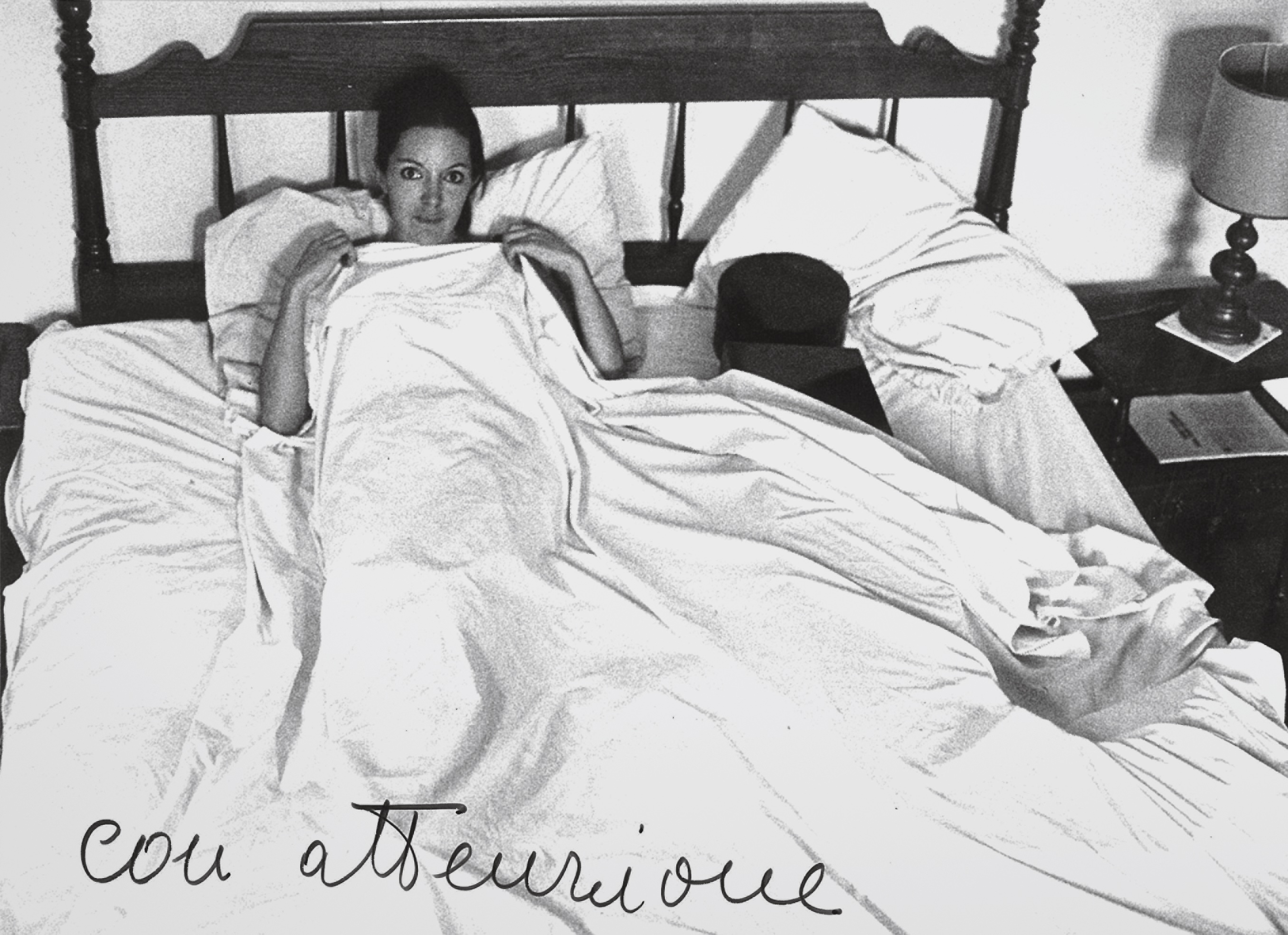

Valie Export in Milan: 'Nowadays we see the body in all its diversity'

Valie Export in Milan: 'Nowadays we see the body in all its diversity'Feminist conceptual artists Valie Export and Ketty La Rocca are in dialogue at Thaddaeus Ropac Milan. Here, Export tells us what the body means to her now

-

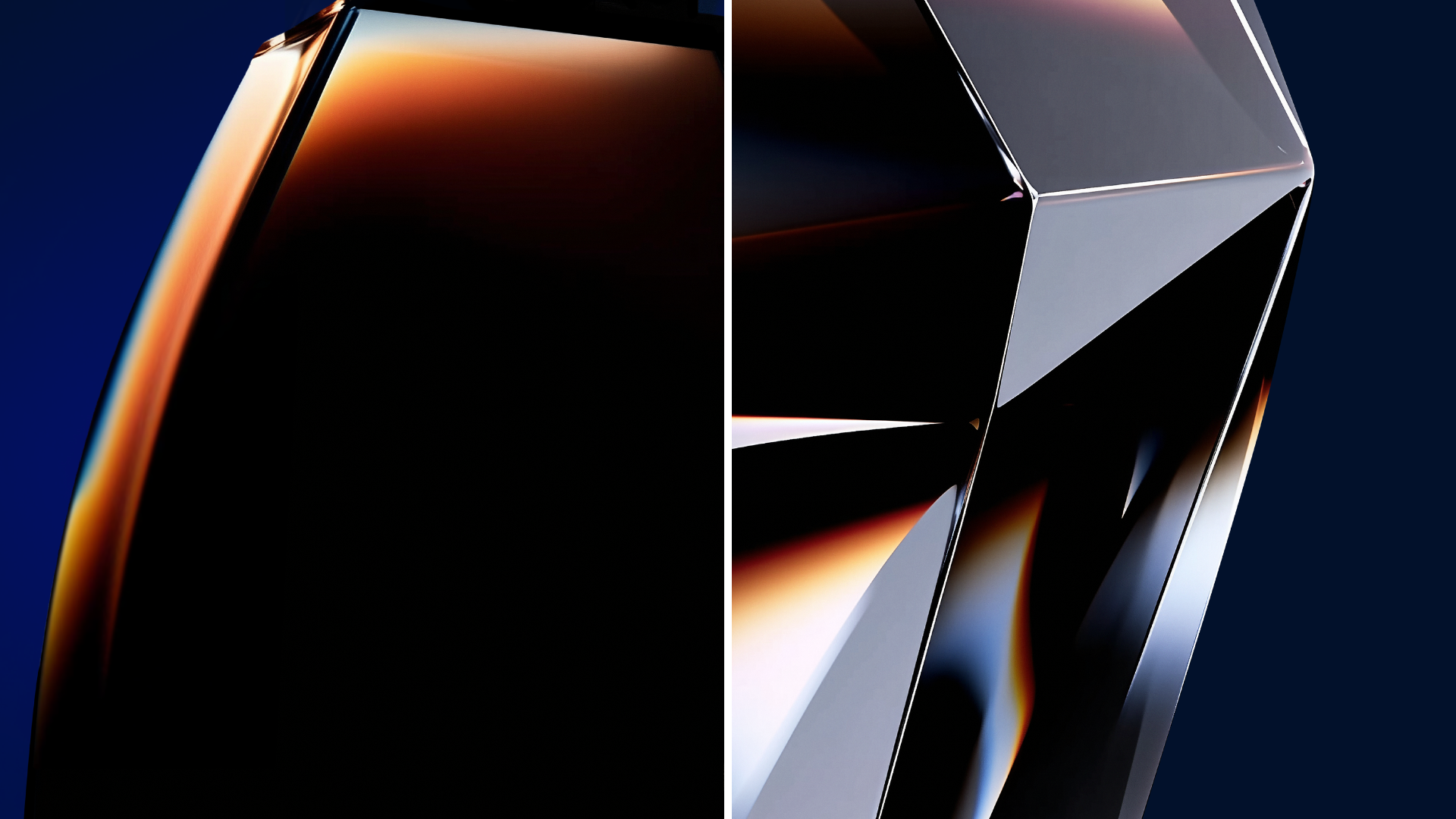

Martell’s high-tech new cognac bottle design takes cues from Swiss watch-making and high-end electronics

Martell’s high-tech new cognac bottle design takes cues from Swiss watch-making and high-end electronicsUnconventional inspirations for a heritage cognac, perhaps, but Martell is looking to the future with its sharp-edged, feather-light, crystal-clear new design

-

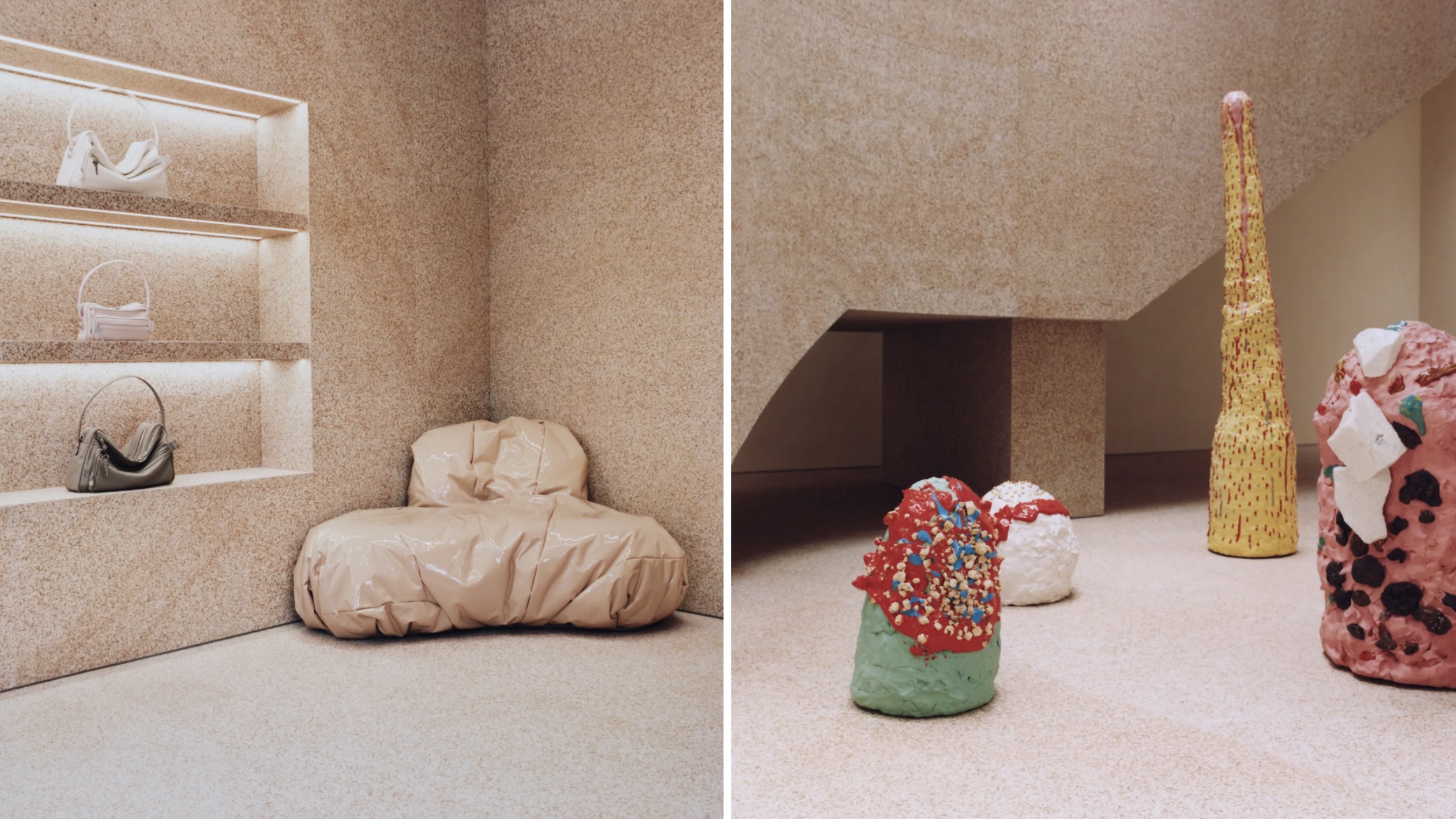

In 2025, fashion retail had a renaissance. Here’s our favourite store designs of the year

In 2025, fashion retail had a renaissance. Here’s our favourite store designs of the year2025 was the year that fashion stores ceased to be just about fashion. Through a series of meticulously designed – and innovative – boutiques, brands invited customers to immerse themselves in their aesthetic worlds. Here are some of the best

-

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of Japan

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of JapanDesigned by MIDW, a house nestled in the south-west Tokyo district features contrasting spaces united by the calming rhythm of structural timber beams

-

Take a tour of the 'architectural kingdom' of Japan

Take a tour of the 'architectural kingdom' of JapanJapan's Seto Inland Sea offers some of the finest architecture in the country – we tour its rich selection of contemporary buildings by some of the industry's biggest names

-

Matsuya Ginza lounge is a glossy haven at Tokyo’s century-old department store

Matsuya Ginza lounge is a glossy haven at Tokyo’s century-old department storeA new VIP lounge inside Tokyo’s Matsuya Ginza department store, designed by I-IN, balances modernity and elegance

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthThis September, Wallpaper highlighted a striking mix of architecture – from iconic modernist homes newly up for sale to the dramatic transformation of a crumbling Scottish cottage. These are the projects that caught our eye

-

Utopian, modular, futuristic: was Japanese Metabolism architecture's raddest movement?

Utopian, modular, futuristic: was Japanese Metabolism architecture's raddest movement?We take a deep dive into Japanese Metabolism, the pioneering and relatively short-lived 20th-century architecture movement with a worldwide impact; explore our ultimate guide

-

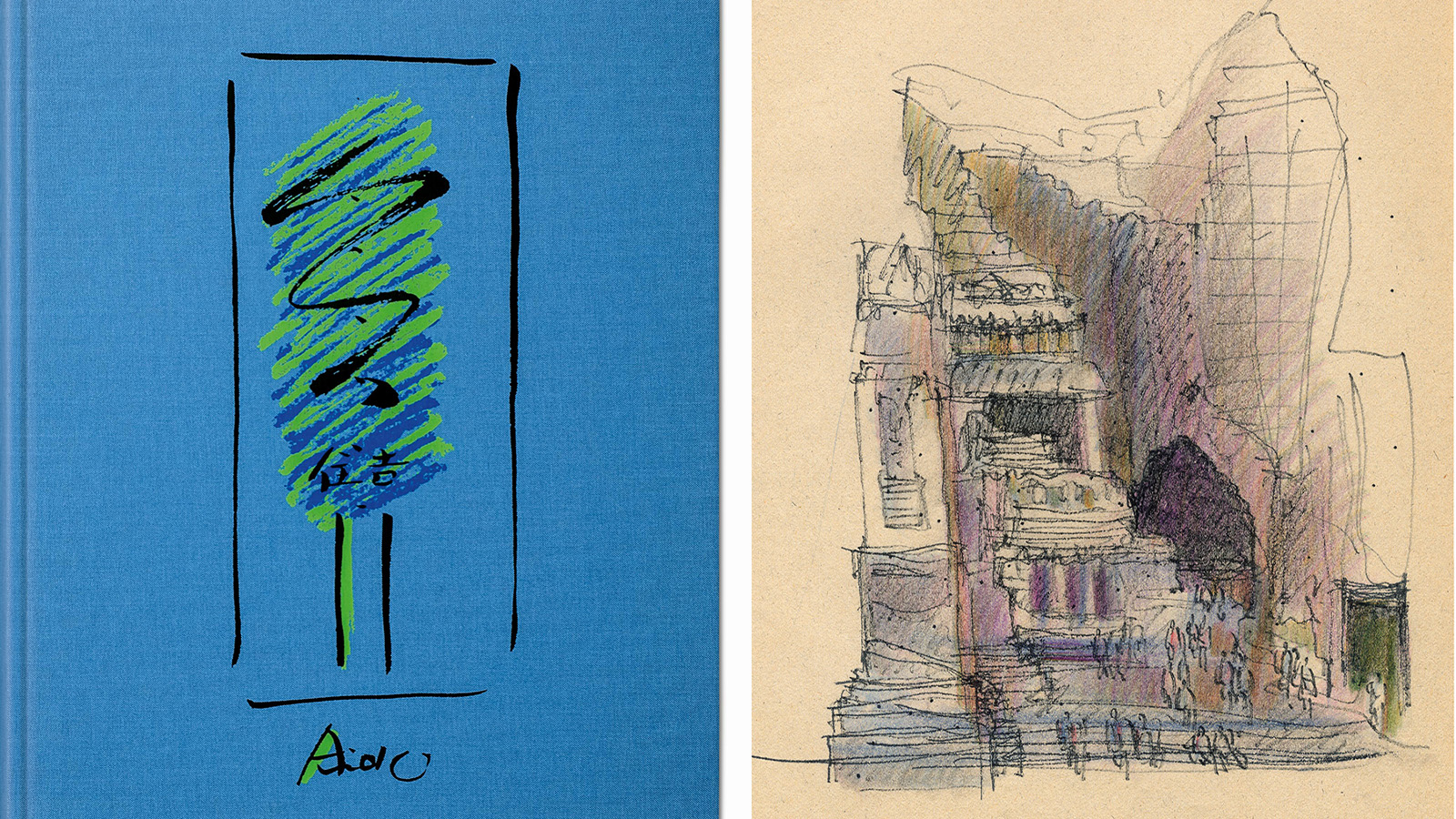

A new Tadao Ando monograph unveils the creative process guiding the architect's practice

A new Tadao Ando monograph unveils the creative process guiding the architect's practiceNew monograph ‘Tadao Ando. Sketches, Drawings, and Architecture’ by Taschen charts decades of creative work by the Japanese modernist master

-

A Tokyo home’s mysterious, brutalist façade hides a secret urban retreat

A Tokyo home’s mysterious, brutalist façade hides a secret urban retreatDesigned by Apollo Architects, Tokyo home Stealth House evokes the feeling of a secluded resort, packaged up neatly into a private residence

-

Landscape architect Taichi Saito: ‘I hope to create gentle landscapes that allow people’s hearts to feel at ease’

Landscape architect Taichi Saito: ‘I hope to create gentle landscapes that allow people’s hearts to feel at ease’We meet Taichi Saito and his 'gentle' landscapes, as the Japanese designer discusses his desire for a 'deep and meaningful' connection between humans and the natural world