Langlands & Bell's modernist box in rural Kent is a work of art

The rural studio-house of Turner Prize 2004 nominees Nikki Bell and Ben Langlands is some 320 sq m of meticulous craftsmanship and canny details, a modernist box in the quintessentially English countryside, couched in a meadow that is mown for its hay every autumn by a local farmer. With characteristic matter-of-factness, the artist couple call it ‘Untitled’.

Finding the site was one of the few accidents in the pair’s well-organised life and the result of deciding, after a lazy, sunny spring day in rural Kent, to take a slow route home on their return to London. It was 2001 and, as they made their way along narrow, winding, back roads, they came upon a dirty ‘For Sale’ sign, stopped the car, found a way through the hedgerow onto the site and discovered a barely habitable cottage with a wide open view across a vast meadow to a clump of trees in the middle distance and a hill beyond.

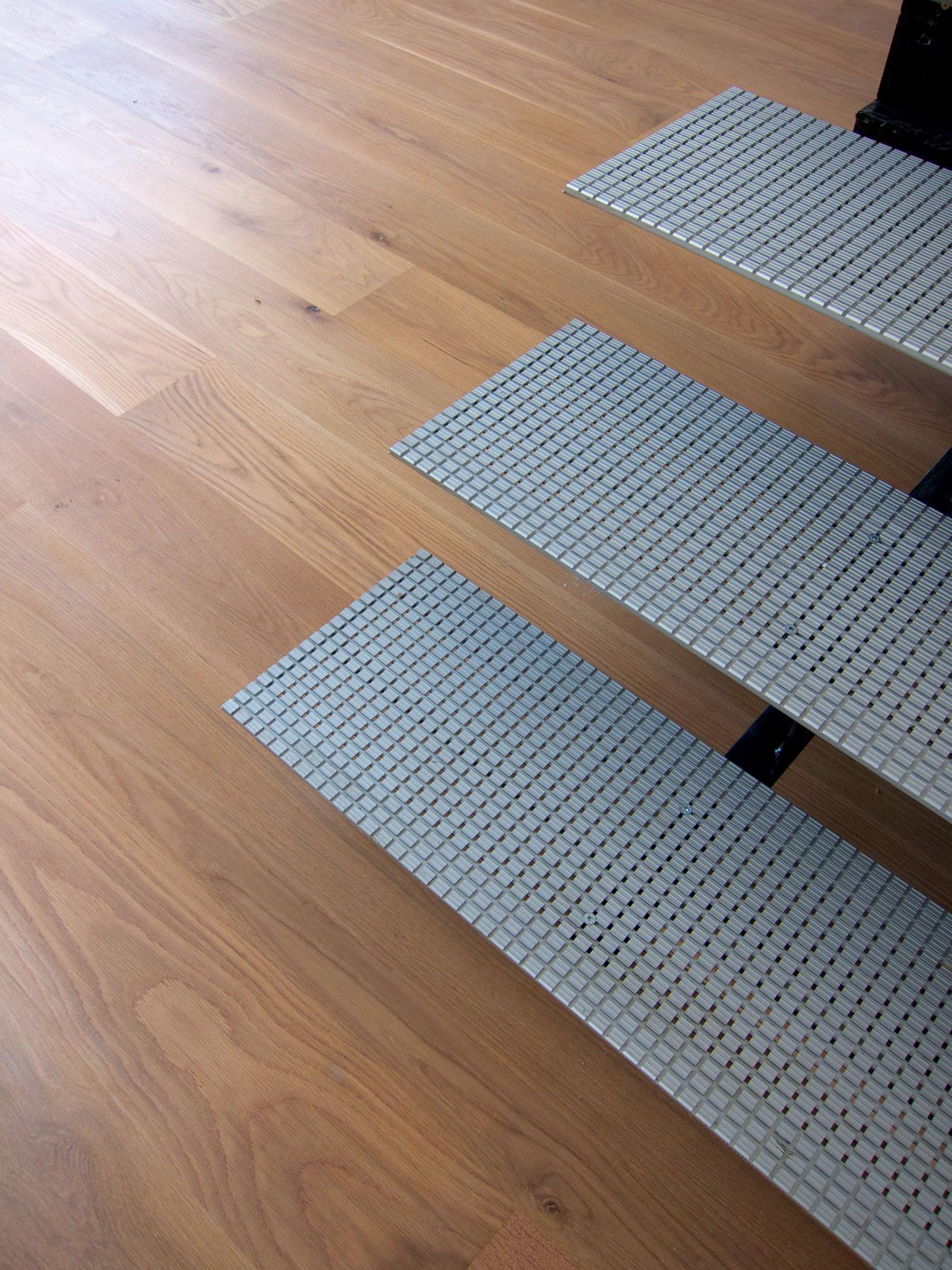

Engineered ply floorboards laminated with oak veneer, and Alcan aluminium steps leading to the studio.

A couple of years later, having assembled enough land from the surrounding farmers to build, they took off for an artistic assignment to cover the invasion of Afghanistan. On their return, it took another year to design the plans with the help of London structural engineers Atelier One, negotiate a supply of water from the neighbouring farmer’s source and get planning permission.

In 2006, they razed the cottage. ‘It was a weird feeling to buy something to tear down in order to build something,’ says Langlands. ‘We’d only ever renovated buildings before [including their four-storey Georgian house in and studio in Whitechapel, east London].’ Then they installed an LPG gas generator and hoisted a converted shipping container onto the site by crane. This doubled as the project manager’s office and living accommodation for Langlands and Bell. ‘We decided against the deluxe version,’ says Langlands, ‘and instead got the £26-a-week model.’ It was a clear case of getting what you pay for. But, resourceful, determined and resilient as always, they managed.

A routine began in which Langlands and Bell opened the gates for the builders at 7:30am, worked with them until 10am, drove back to London to continue work in the studio, then returned to the site with blankets and an electric heater at 10pm to spend the rest of the night there.

Exterior Alcan aluminium steps.

Most visual artists don’t make good architects (and vice versa). But the artwork of Langlands and Bell has always been based on representations of space, scale and dimension. They began working in the third dimension at Hornsey College of Art (where Anish Kapoor and Richard Wilson were among their fellow students) when they collaborated for the first time on an installation that they named The Kitchen.

The structure of their new house seems simple – a double L-shaped, single-storey, flat-roofed box devoid of the extraneous. But once you’re inside, the sophistication of the design becomes clear. Resting on concrete pilings sunk 7m into the Kent clay soil, the core of the building contains a small lobby that serves as coat cupboard, mud room and wood storage, and opens into a vast space, lined on one side with sliding glass doors. A wall on one short leg of the L screens a gallery kitchen and door to the garage/workshop. Doors at the other end of the building open into a guest bedroom, the master bedroom and shower, steps down to a double-height studio and steps up to the roof where a minimalist Japanese cedar bath designed by Claudio Silvestrin, the gift of a friend, offers a long view to a traditional country church on a distant hill.

The structure is served by an intricate combination of old-fashioned methods and dazzling new technology: a massive 4,000-gallon rainwater harvesting tank; a modified septic tank for waste; propane gas; a generator specially made in Ireland to function as a combined heat and power (CHP) unit controlled by a micro chip; a back-up generator; underfloor heating powered by the CHP and solar panels on the roof; and a stainless-steel Scandinavian wood-burning stove. An agricultural engineer has installed an accumulator tank that stores water at the proper pressure and an inverter that turns 12 volts in 240 volts with batteries to store the surplus electricity harvested from the solar panels.

A wooden statue of St Theresa of the Roses, salvaged from a fire-bombed church in 1985.

Insulation to offset the heat loss from the double-glazed, Low-E glass sliding windows is 6in-thick wood fibre. Tiles on the roof are made from recycled rubber tyres. Other ecologically correct materials include oak cladding from sustainable French forests; engineered ply floorboards laminated with 10mm oak veneer, specially designed for underfloor heating, and cross-laminated timber panels that can bear heavy structural loads, have good insulating properties and dampen sound.

Thanks to the skills that Langlands and Bell developed at the start of their career, before they could afford to get others to fabricate the artworks they conceived, their input is DIY as it’s never been seen before. They constructed all the MDF cupboards with Corian tops, glued the mirror glass panels to the internal doors and, using local fitters, installed the kitchen and bathroom fixtures.

While the diversity of the materials used forms a whole that is surprisingly reticent, it is matched by the much more obvious diversity of the building’s setting. There are native hedges of blackthorn, hawthorn, hornbeam, hazel and goat willow, self-seeding oaks, guilder and dog rose bushes, and field maples. Barn owls roost in oak trees just outside the house and share sky and nesting places with tawny owls, herons, kestrels, buzzards and pheasants, one of whom regularly pecks on the sliding doors. Badgers and rabbits abound and two newly installed bat houses, another housewarming present, await habitation by the bats that frequent the property. Sited comfortably in such a rich natural environment, the house is proof that respect for nature and meticulous attention to detail can make steel, aluminium and glass seem as natural as unprocessed materials.

A Moroccan flag in the library.

Langlands and Bell have even, in some places, transformed nature into art and by the simplest of means: a window that perfectly frames an oak tree; a view of a counterpoint white house in the distance that appears to be directly aligned with their building; a mushroom circle that only becomes visible when the meadow is mown. Natural disorder, too, is deftly organised to create memorable images, as in the workshop where a white overall is hung in such a way that it becomes an eerie presence in the space.

The result of all the care and creative energy expended is a comfortable, highly efficient live/work space that is barely there. ‘Untitled’, by Langlands and Bell, appears to be transparent, constructed only of views of land and sky, reflections of reflection and seemingly solid shafts of sunlight. ‘It’s not architecture,’ says minimalist architect and friend John Pawson. ‘It’s an installation.’

See a photographic story of the making of the house here

As originally featured in the May 2011 issue of Wallpaper* (W*146)

The artists’ ‘Interlocking Chair’ (1989) sits in their studio, looking out over a vat window.

The artists carried out much of the interior work themselves, including lining the internal doors with mirror.

The workshop where Langlands and Bell realise some of their ideas.

Nikki Bell and Ben Langlands on top of the MDF/Corian cupboards they constructed in their countryside idyll.

One side of the double L-shaped house is a wall of sliding glass doors, overlooking oak trees where barn owls roost.

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Langlands & Bell website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

In search of a seriously-good American whiskey? This is our go-to

In search of a seriously-good American whiskey? This is our go-toBased in Park City, Utah, High West blends the Wild West with sophistication and elegance

By Melina Keays Published

-

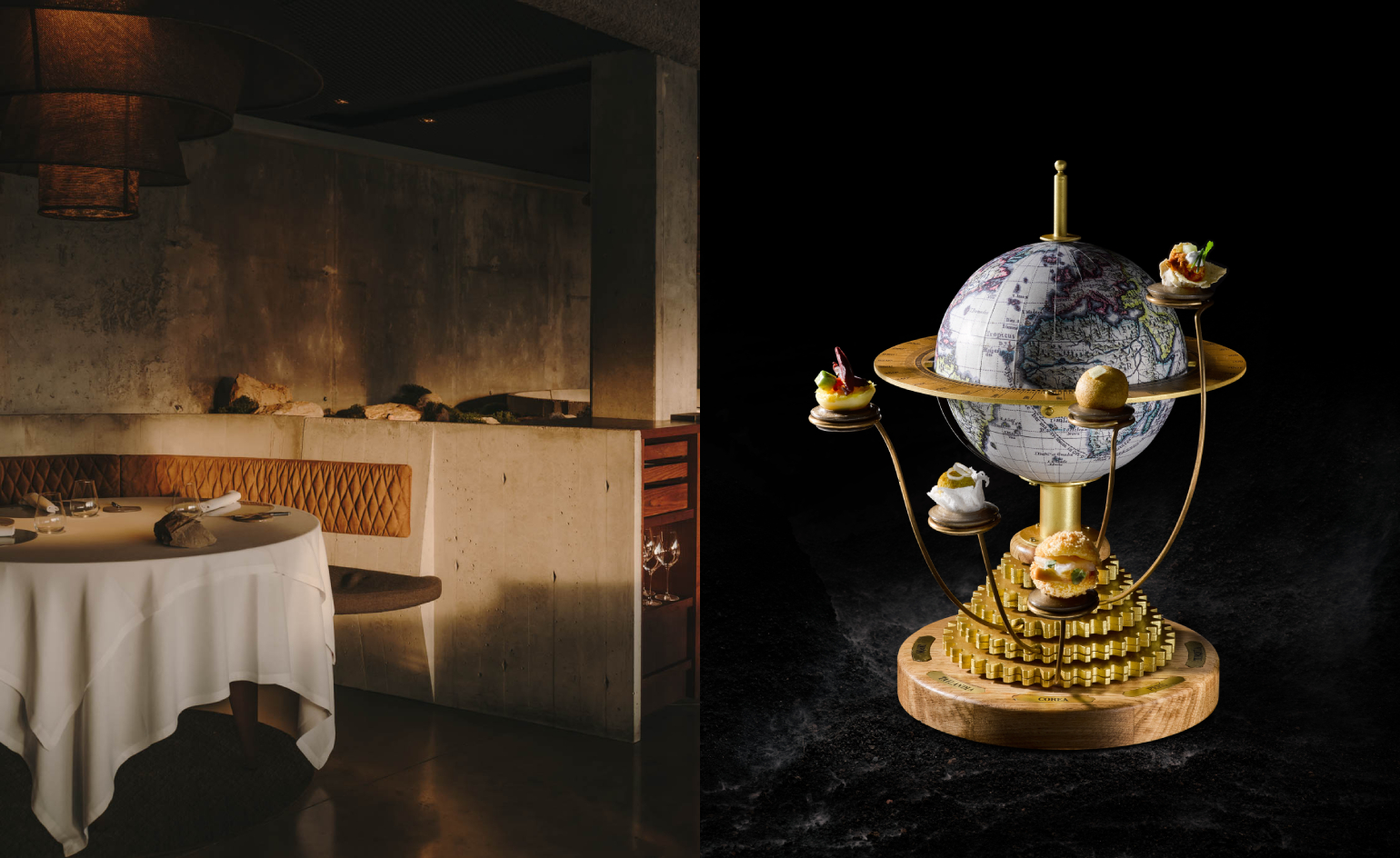

Esperit Roca is a restaurant of delicious brutalism and six-course desserts

Esperit Roca is a restaurant of delicious brutalism and six-course dessertsIn Girona, the Roca brothers dish up daring, sensory cuisine amid a 19th-century fortress reimagined by Andreu Carulla Studio

By Agnish Ray Published

-

Bentley’s new home collections bring the ‘potency’ of its cars to Milan Design Week

Bentley’s new home collections bring the ‘potency’ of its cars to Milan Design WeekNew furniture, accessories and picnic pieces from Bentley Home take cues from the bold lines and smooth curves of Bentley Motors

By Anna Solomon Published

-

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yoursJean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

By Amy Serafin Published

-

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, UzbekistanThe legacy of modernist architecture in Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent, is explored through research, a new publication, and the country's upcoming pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; here, we take a tour of its riches

By Will Jennings Published

-

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?DeafSpace learnings can help create profoundly sense-centric architecture; why shouldn't groundbreaking designs also be inclusive?

By Teshome Douglas-Campbell Published

-

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from Koto

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from KotoThe Niwa modular cabin series by UK-based Koto architects offers a range of elegant retreats, designed for easy installation and a variety of uses

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

How Le Corbusier defined modernism

How Le Corbusier defined modernismLe Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?Property developer Derwent London’s new lounges – created for tenants of its offices – work harder to promote community and connection for their users

By Emily Wright Published

-

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in Oxford

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in OxfordThe Gradel Quadrangles, designed by David Kohn Architects, brings a touch of playfulness to Oxford through a modern interpretation of historical architecture

By Shawn Adams Published