Inside artist Loris Gréaud’s Paris studio, a concrete bunker by Claude Parent

French artist Loris Gréaud invites us into his light-filled, bunker-like studio, the final project of late architect Claude Parent – watch the exclusive film

Marine Pérault – film

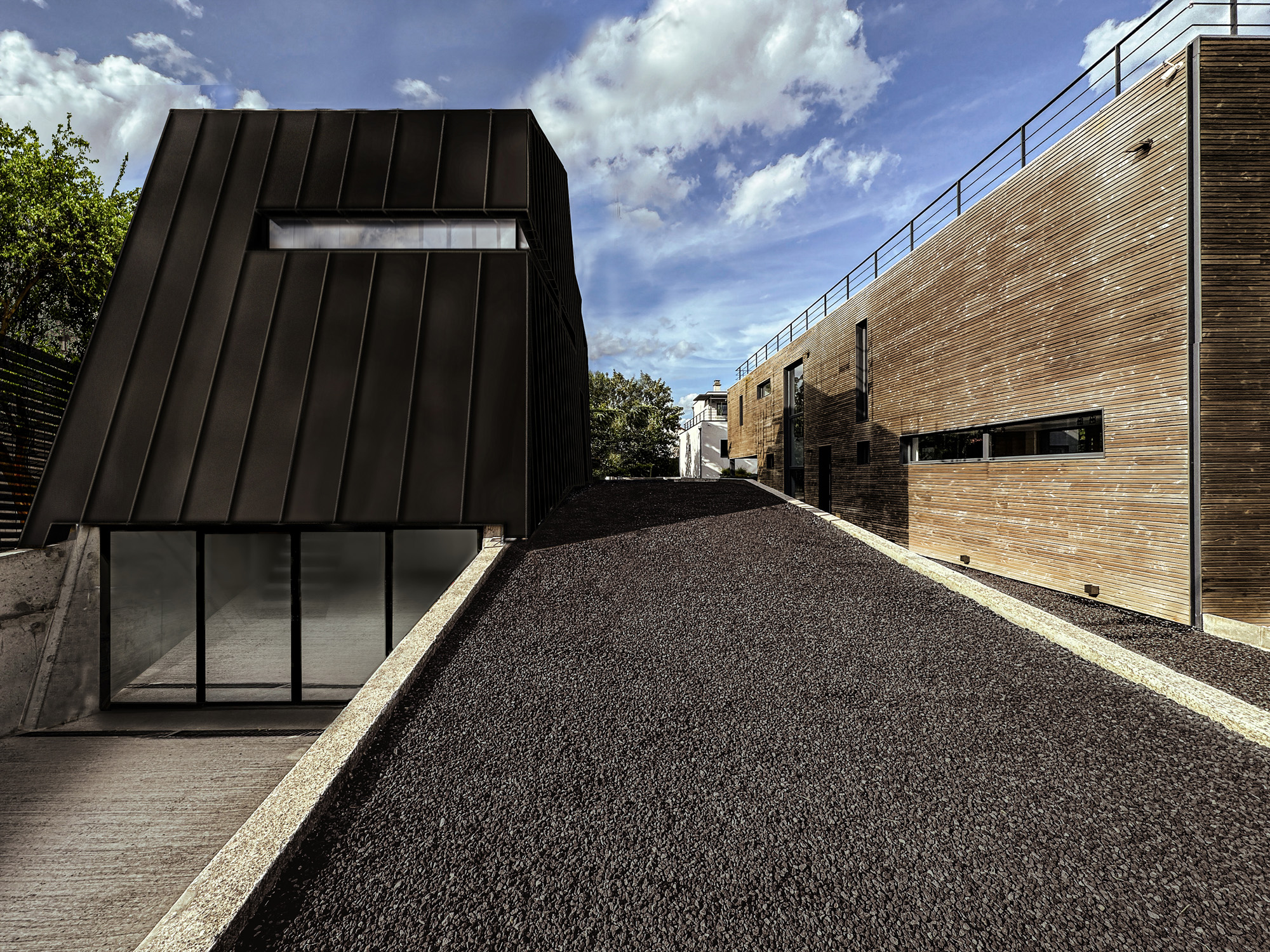

Eaubonne, an unassuming suburb north of Paris, is not where you’d expect to find a brutalist bunker by the late architect Claude Parent, rising up like a shark fin in a sea of stucco houses. But Eaubonne also happens to be the home of artist Loris Gréaud, who thrives on the unexpected.

Gréaud has garnered a reputation for artworks that mess with viewers’ perceptions, flickering between reality and illusion. He created an underground sculpture park that nobody can see, destroyed a museum exhibit on the night of its opening, and shot a two-hour film for one viewer to watch at a time.

As a teenager, he was entranced by the drawings of Parent, a utopian thinker who,in the 1960s, co-developed an architectural theory called ‘la fonction oblique’, using sloped planes to prioritise space over surface. Later, when Gréaud established his name as an artist, he searched for a good reason to collaborate with Parent, finally finding one in 2014, in the context of his feature film, Sculpt.

See Claude Parent and Loris Gréaud collaborate

In this exclusive extract for Wallpaper*, Loris Gréaud gives voice to the story of his collaboration with Claude Parent, and offers us a glimpse into the creative partnership of artist and architect. From 'A Fluid Universe: Loris Gréaud — Claude Parent', a film by Marine Pérault, to be released in 2024.

The French art dealer Yvon Lambert, who represented Gréaud and exhibited Parent’s drawings, arranged the meeting. Gréaud remembers being very nervous. ‘I entered and saw a small man who was very elegant, funny, chic. I tried to explain my idea as clearly as possible: “I would like to commission an architecture of the mind that an actress can walk around in and record her cerebral activity.” He didn’t say yes right away.’ Two weeks later, Parent asked Gréaud to come back. He had started sketching a building in India ink. He said he wanted to help, but that they had ‘to work together, and create a physical model before ending up with an architecture of the mind.’

Chloé Parent, Claude’s daughter, notes that Gréaud touched something in her father that had long been dormant. As a young architect, Parent worked with Yves Klein and other artists, but later in life, he lost the desire. ‘Loris is one of the rare contemporary artists to have rekindled this flame, this interest and surprise in art,’ she says.

Artist and architect started collaborating every Wednesday, building a model in clay and wood. Gréaud was impressed that Parent went through each of these steps – drawing, modelling, even adding an entrance ramp – for a project that was ultimately imaginary. ‘I understood that, for him there was no utopia,’ he says, ‘because everything had to be buildable.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Gréaud at the studio in an ‘LC4’ chaise longue, by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand, with his cats Erwin and Erwin, named after Schrödinger and his famous thought experiment

Two years after their first meeting, a small plot next to Gréaud’s studio came up for sale. He worked up the courage to ask Parent to design him a new studio, a real building this time. Parent quickly agreed.

Knowing it might be difficult to score a building permit for a brutalist monolith in his town, Gréaud invited the then-mayor of Eaubonne to an exhibition on Parent and Jean Nouvel (Parent’s one-time assistant) in Paris. It worked, and Parent, who had suffered a stroke three months earlier, lived long enough to know there would be one more building to his name. ‘We went to see him at the hospital,’ Gréaud recalls.

‘Naad [Parent’s wife] asked us to bring the model. I entered the room and he mistook me for a young architect working on the project. He said, ‘Ah, that’s the building the artist commissioned. Bring it here. Now, you’ll have to fix this slope…’ He didn’t recognise me, but he recognised the work, and the things that needed to be corrected.’ Parent died shortly afterwards, in 2016.

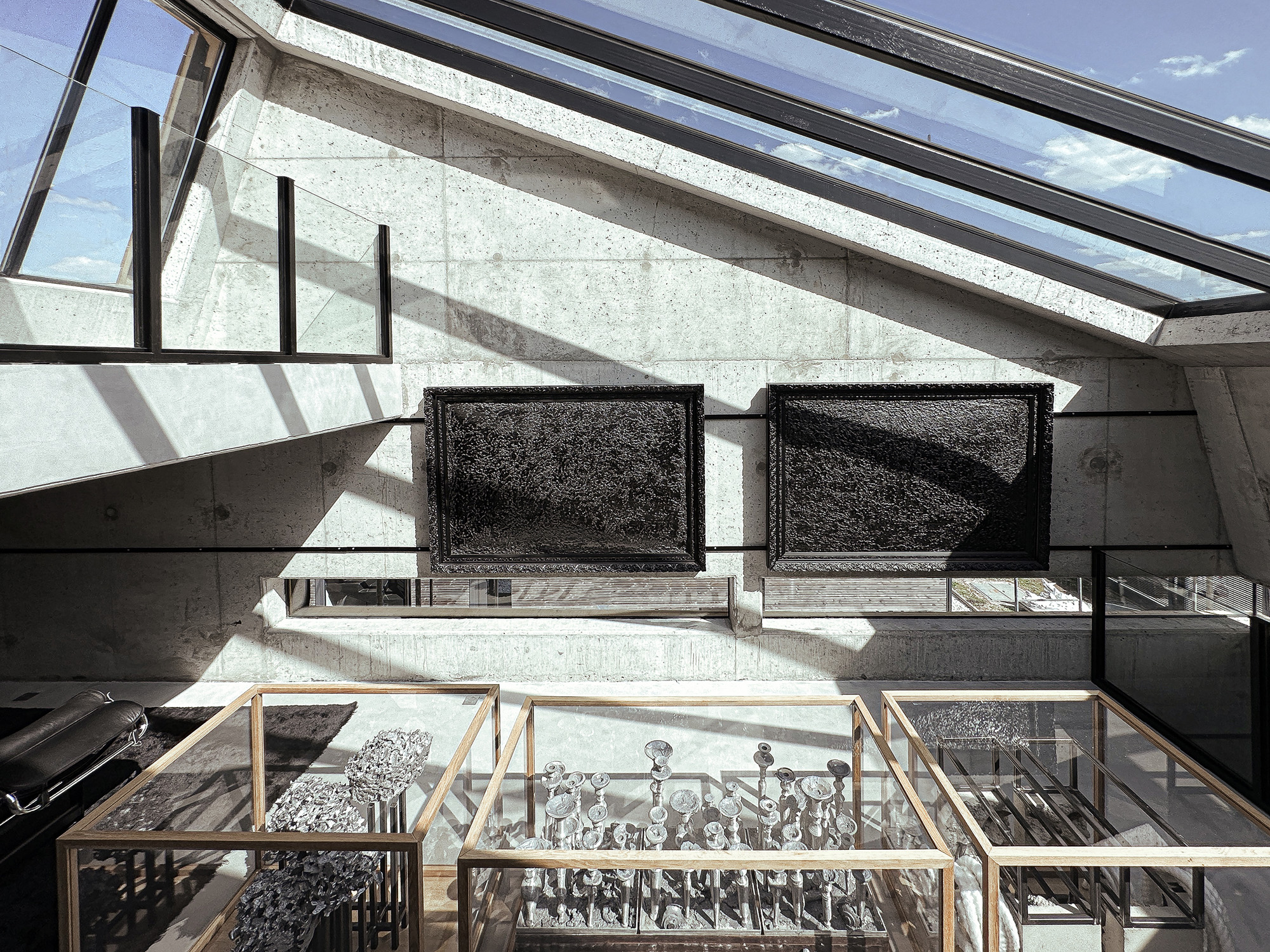

Two artworks from Gréaud’s Reject of a primitive mental structure series, 2014, hang above cabinets displaying Crossroad, 2015-2023, a work in progress

The design of the building, a concrete bunker, is simple in theory. But slanted concrete walls are more complicated to pour than straight ones, and it took three years to complete the technical and structural plans before construction started in 2019. Gréaud had factored this timeline into his planning. However, he could not have anticipated Covid, which made the project the most difficult challenge he has ever faced. ‘It will be my downfall,’ he says, only half joking.

Like the rest of the world, he had to deal with a shortage of construction workers, and the inflated prices of materials, which he says quadrupled his costs. Parent conceived the building so that a ‘cannon’ of light would enter through a glass roof and travel all the way to the bottom. But the roof could not be installed before the concrete envelope was complete. After Gréaud’s concrete supplier went bankrupt, the construction site turned into what he calls ‘one of the world’s most beautiful swimming pools’ for nearly two long years. Living next door, all the artist could do was watch, helplessly. ‘It comes back to an architecture of the mind – when it rained in the building, it rained inside of us.’

Nonetheless, the project inched forward, and, once the black zinc cladding was installed in summer 2023, the building was finally complete. In 2020, a year before she passed away, Naad went to visit, and told Gréaud she felt her husband’s spirit within. Chloé says the building is ‘a return to the piercing of the mass to let light in’ and compares it to her father’s Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay church in Nevers, central France. ‘It’s a shelter, a rampart, a grotto that is keeping the art and artist safe, the same way Sainte-Bernadette is keeping the spirituality and the believer safe.’

A long, narrow window slashes through a corner of the zinc-clad building. Before cutting the window, the concrete specialists required that Gréaud sign a liability waiver, as they thought it would crumble under six tonnes of concrete

Dubbed the Workshop, Gréaud’s new studio is a space where the artist will work alone, with his hands, in resin, sculpture and paint. When he shows off the site, his enthusiasm reveals that this is not a folly but an environment that will boost his creative energy. The complementarity between his work and Parent’s building is striking; older artworks set against the oblique walls look like they were made for this place.

From the exterior, the Workshop appears small. But inside, it’s surprisingly spacious, with four levels and three parallel stairways. To meet height regulations, Parent slanted the terrain, putting level ‘0’ above street level and obtaining an extra 2.2m underneath. The underground foundation, a thick slab of concrete, has some of Gréaud’s artworks literally buried within, invisible to all.

Now that the studio is complete, Gréaud has further plans for the rest of the 1,050 sq m property. His team will continue to work in the original studio next door, which he himself designed. Behind it, his current house will become an exhibition space for what he refers to as ‘immersive installations’.

Next, the renowned architect Dominique Perrault, a friend, will design a new house for Gréaud behind Parent’s studio. Perrault says he will embed the house in the ground like an ancient Ethiopian church, linking the different buildings underground. ‘There are already a lot of buildings on this small plot, so I find it an interesting idea to create another that links the existing ones, though not visually. The idea is to be there and be absent.’

The Workshop’s completion coincided with the 100th anniversary of Parent’s birth, and it is hard to think of a better way to mark the event. ‘It is Claude’s last building, a testament building,’ says his daughter. ‘But a happy testament, full of vitality, strength and art. It resembles him and proves that his rebellious spirit was still intact.’

Gréaud’s solo exhibition ‘Cortical Nights’ is on show at the Petit Palais, Paris 8e, from 4 October 2023 - 31 January 2024, corticalnights.com

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.

-

A day in Ahmedabad – tour the Indian city’s captivating architecture

A day in Ahmedabad – tour the Indian city’s captivating architectureIndia’s Ahmedabad has a thriving architecture scene and a rich legacy; architect, writer and photographer Nipun Prabhakar shares his tips for the perfect tour

-

You can now stay in one of Geoffrey Bawa’s most iconic urban designs

You can now stay in one of Geoffrey Bawa’s most iconic urban designsOnly true Bawa fans know about this intimate building, and it’s just opened as Colombo’s latest boutique hotel

-

Pentagram’s identity for eVTOL brand Vertical Aerospace gives its future added lift

Pentagram’s identity for eVTOL brand Vertical Aerospace gives its future added liftAs Vertical Aerospace reveals Valo, a new air taxi for a faster, zero-emission future, the brand has turned to Pentagram to help shape its image for future customers

-

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the market

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the marketAndré Wogenscky was a long-time collaborator and chief assistant of Le Corbusier; he built this home, a case study for post-war modernism, in 1957

-

‘You have to be courageous and experimental’: inside Fondation Cartier’s new home

‘You have to be courageous and experimental’: inside Fondation Cartier’s new homeFondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain in Paris invites us into its new home, a movable feast expertly designed by Jean Nouvel

-

A wellness retreat in south-west France blends rural charm with contemporary concrete

A wellness retreat in south-west France blends rural charm with contemporary concreteBindloss Dawes has completed the Amassa Retreat in Gascony, restoring and upgrading an ancient barn with sensitive modern updates to create a serene yoga studio

-

Explore the new Hermès workshop, a building designed for 'things that are not to be rushed'

Explore the new Hermès workshop, a building designed for 'things that are not to be rushed'In France, a new Hermès workshop for leather goods in the hamlet of L'Isle-d'Espagnac was conceived for taking things slow, flying the flag for the brand's craft-based approach

-

‘Landscape architecture is the queen of science’: Emanuele Coccia in conversation with Bas Smets

‘Landscape architecture is the queen of science’: Emanuele Coccia in conversation with Bas SmetsItalian philosopher Emanuele Coccia meets Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets to discuss nature, cities and ‘biospheric thinking’

-

An apartment is for sale within Cité Radieuse, Le Corbusier’s iconic brutalist landmark

An apartment is for sale within Cité Radieuse, Le Corbusier’s iconic brutalist landmarkOnce a radical experiment in urban living, Cité Radieuse remains a beacon of brutalist architecture. Now, a coveted duplex within its walls has come on the market

-

Maison Louis Carré, the only Alvar Aalto house in France, reopens after restoration

Maison Louis Carré, the only Alvar Aalto house in France, reopens after restorationDesigned by the modernist architect in the 1950s as the home of art dealer Louis Carré, the newly restored property is now open to visit again – take our tour

-

Meet Ferdinand Fillod, a forgotten pioneer of prefabricated architecture

Meet Ferdinand Fillod, a forgotten pioneer of prefabricated architectureHis clever flat-pack structures were 'a little like Ikea before its time.'