Ludwig Godefroy’s brutalist Casa Mérida in Mexico

Concealed concrete courtyards and cool garden rooms make for a contemplative hideaway in Mérida, Yucatán

The tallest structure is set at the centre of the plot and houses an upper-level bedroom, accessed via a pyramid-like concrete staircase that nods to local Mayan architecture.

The first thing that stands out about Casa Mérida is its unashamed brutalism, defined by raw and omnipresent concrete, all hard edges and rough surfaces under the strong Mexican sun. The second is that most of the building seems to be open to the outdoors, with few fully enclosed spaces. The project’s defining feature, though, is that it is 80m long but just 8m wide.

While this odd stretch would be considered unusual in most places, in Mérida, capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán, it’s fairly common, explains the house’s architect, French-born, Mexico City-based Ludwig Godefroy: ‘This type of lot is everywhere in the historic centre of Mérida and it has to do with inheritance, when people started to slice bi er plots into smaller ones, to distribute to different siblings.’ And while a big part of the city comprises grand colonial architecture, some urban chunks include more humble styles, such as old workers’ cottages. It was one such building that Godefroy came across, when he visited Mérida with his client, a high-flying professional from Mexico City. His family of three was in search of the perfect spot for a retreat, to hide away and use as a base to kite-surf nearby.

The strange plot was a quirk Godefroy embraced immediately. ‘The house’s long and narrow site provided a new kind of challenge for me,’ he says. ‘It’s nothing like I’ve done before and by pushing yourself, something new and amazing can come up.’

And come up it did, as the wildly di erent design emerged, transforming the existing structure into a 21st-century ascetic refuge. Taking the site as the main inspiration, Godefroy started to explore the possibilities; he also looked to the local culture and vernacular as well as personal in uences, constantly adjusting areas until the whole project felt just right, both answering the client’s needs and tting in the urban context.

Exposed concrete formwork gives texture to the walls and shower enclosure of one of the bedrooms

The site’s history was important for Godefroy: ‘I wanted to keep elements of the old house as testimony to what was there before, so I decided to leave it as a sort of ruin. From the street you cannot really see the new house, it’s like a secret garden house and the old home essentially becomes the entrance to the new design,’ he says. So while the interior is entirely new, the front façade and old building’s bones were kept, revealing nothing about what goes on behind the enigmatic street-facing stone wall.

Once past the front door and a walled entrance hall with a garage next to it, everything changes. ‘This is not a house with a garden. It is a garden with a house,’ explains the architect. Making the most of the region’s warm weather and taking his cues from the outdoor lifestyle of the locals, Godefroy composed a journey through a sequence of permeable spaces along the plot’s long axis, dotted with four courtyards. This helps negotiate the awkward length, which otherwise could have meant a series of dark rooms.

Meanwhile, an open-air strip running the entire length of the house acts as a backbone for the design. ‘The long corridor on the side of the plot helps with ventilation but also acts as the main circulation space,’ he continues. ‘When moving through the house you always come back there.’ The various courtyards alternate with living areas and bedrooms, one of which can be used as a studio, with its own kitchenette and bathroom. Another is slotted on an upper level, under a concrete, pyramid-esque roof that nods to Mayan culture – a key part of Mérida’s heritage.

‘Casa Mérida is not a house with a garden. It is a garden with a house’

Sculptural concrete appears everywhere and unites the whole, forming anything from reading nooks and benches to ceiling beams, unexpected openings and even three oversized rainwater collectors (which help return water into the subsoil through absorption wells). The house’s main social area is located towards the rear, far from street noise, for peace and privacy.

The walk through the plot’s 80m culminates in a spectacular, secluded swimming pool, which is fully wrapped in concrete and inspired by cenotes (natural sinkholes found all over the region, considered sacred by the Mayan people). Apart from such references to local culture, there’s also something rather modernist in the house’s clarity, and the architect admits to in uences from the great masters. ‘I tend to mix brutalism with archaeological sites and vernacular architecture, all in the simplest way possible,’ he says. ‘I wanted this house to symbolise a return to a simple way of life.’ He cites Juliaan Lampens, Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn and Aldo van Eyck as references.

Bold colour is distinctly absent from the house, which mixes Mayan cream stone, naked grey concrete and pine wood in a fairly neutral colour palette. This adds to the overall calming effect, and underlines the house’s role as a sanctuary. Fittingly, there are plenty of hammocks; a shorthand for relaxation, these are also central to the local way of life (Yucatán is renowned for handwoven Mayan hammocks). ‘I made sure there is the option to put a hammock in most places in the house,’ says Godefroy. It’s the perfect invitation to relax.

As originally featured in the December 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*249)

The dining room and kicthen opens on to one of the four courtyards

A hammock hangs above the swimming pool, which is inspired by local sinkholes

Sculptural concrete unifies the 80m long site

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Introducing the design-led Split Watches, a force for good

Introducing the design-led Split Watches, a force for goodGood design is given a charitable spin by Split Watches – for every one sold, the company donates an hour of therapy

-

Meet the New York-based artists destabilising the boundaries of society

Meet the New York-based artists destabilising the boundaries of societyA new show in London presents seven young New York-based artists who are pushing against the borders between refined aesthetics and primal materiality

-

Inside a Montana house, putting the American West's landscape at its heart

Inside a Montana house, putting the American West's landscape at its heartA holiday house in the Montana mountains, designed by Walker Warner Architects and Gachot Studios, scales new heights to create a fresh perspective on communing with the natural landscape

-

A guide to modernism’s most influential architects

A guide to modernism’s most influential architectsFrom Bauhaus and brutalism to California and midcentury, these are the architects who shaped modernist architecture in the 20th century

-

What is eco-brutalism? Inside the green monoliths of the movement

What is eco-brutalism? Inside the green monoliths of the movementThe juxtaposition of stark concrete and tumbling greenery is eminently Instagrammable, but how does this architectural movement address the sustainability issues associated with brutalism?

-

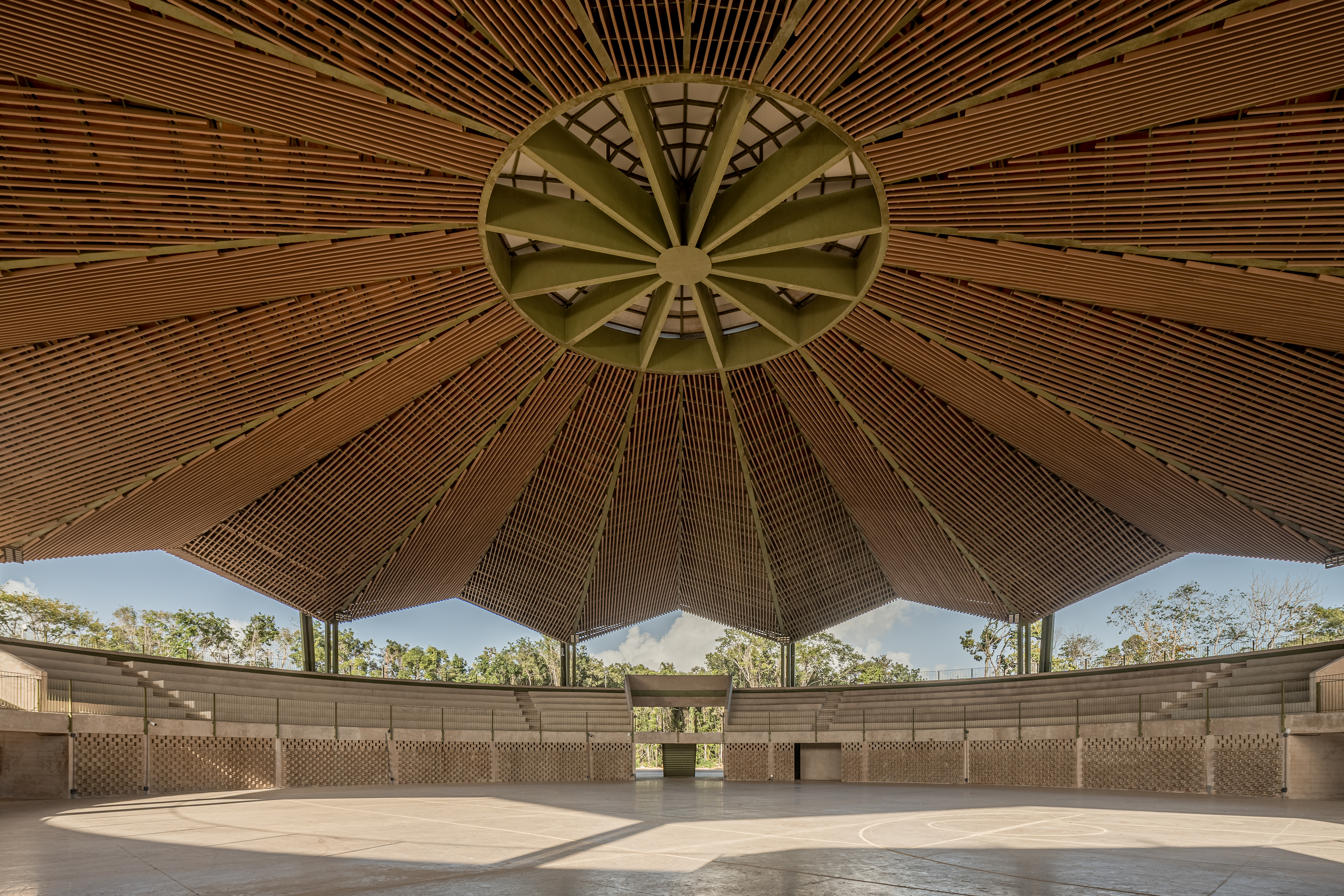

In Quintana Roo, a park mesmerises with its geometric pavilion

In Quintana Roo, a park mesmerises with its geometric pavilionA Mexican events venue in the state of Quintana Roo rings the changes with a year-round pavilion that fosters a strong connection between its users and nature

-

Casa La Paz is a private retreat in Baja California full of texture and theatrics

Casa La Paz is a private retreat in Baja California full of texture and theatricsLudwig Godefroy designed Casa La Paz in Baja California, Mexico to create deep connections between the home and its surroundings

-

Pedro y Juana's take on architecture: 'We want to level the playing field’

Pedro y Juana's take on architecture: 'We want to level the playing field’Mexico City-based architects Pedro y Juana bring their transdisciplinary, participatory approach to the Mexico pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; find out more

-

Brutalism’s unsung mecca? The Philippines

Brutalism’s unsung mecca? The PhilippinesPhilippine brutalism is an architecture subgenre to be explored and admired; the brains and lens behind visual database Brutalist Pilipinas, Patrick Kasingsing, takes us on a tour

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world