The walls and windows don’t seem to be there. From carpet to concrete to plants and trees, rooms are just part of the gradient. They don’t as much end as fade away. Certainly, walls and windows do exist here in this 1955 home designed by architect Archibald Quincy Jones, but whether inside or outside, there’s no connection lost to what’s behind the glass.

This fluid interplay of in and out is partly enabled by its setting in the upscale Los Angeles neighbourhood of Holmby Hills. Hardly distinguishable from the neighbouring Beverly Hills in its opulence and exclusivity, Holmby is a landscape of large estates whose separation from one another creates discrete and discreet universes where what happens is rarely seen by or known to neighbours, even those right next door. But mostly, this connection between the in and out is emblematic of the style of Jones who, with his partner Frederick Emmons, designed dozens of homes throughout the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, helping define midcentury modernism on the West Coast. Homes like this one became poster children for the movement.

The house sits secluded among cacti, trees and native grass. A series of contemporary works, such as this Urs Fischer installation, Bad Timing, Lamb Chop! (2004–05) representing a giant chair embracing a packet of cigarettes, are on display in the garden.

The owners of this particular house – who over the years have included a Hollywood grab bag of movie stars, art gallery owners, casino moguls and internet millionaires – add fitting cachet. Originally commissioned by the Academy Award-winning actor Gary Cooper in the early 1950s, the house is built from wood, glass and stone – all intermixed throughout, appearing both inside and out.

The living area is spread across a single level, and the house’s most striking feature is the angled roof, which rises gradually to jut dramatically above the rest of the flatness of the house. Clad with golden orange-stained wood planks, the roof contrasts with the white plaster and white-rock walls that dominate the front façade and the large windows that make up much of the rear. The wood of the roofline and the tall beams that support it straddle the interior and exterior spaces, as do the rocks. The strong straight lines formed by the post-and-beam structure are simple and elegant, features that are common to Jones’ work.

Water splashing down a rock wall in the front creates a tranquil soundtrack as you enter along the terrazzo walkway, covered by a steel overhang, through the front door into the large, open-plan living room. Arranged over more that 5,700 sq ft, with four bedrooms, the house is now home to an extravagant collection of art and contemporary design, covering every available wall space. Tables and chairs by the designer Marc Newson are scattered throughout the house, sculptures by John Chamberlain and Takashi Murakami shine in the ample sunlight, while photos by Richard Avedon and Cindy Sherman are given entire walls to themselves.

The house at night, with Richard Prince's giant ‘Tire' planter by the pool, and Damien Hirst‘s Thirty-Four Pills seen inside, next to the sofa.

Towards the tallest part of the room, a dining table is surrounded by a dozen chairs and blocked slightly off from the rest of the space with a moveable wooden wall. It’s just tall enough to feel separate, yet not isolated. The angled roof overhead slowly brings the ceiling down from 20ft to ten, while the large wooden vertical beams and the fireplace all subtly segment the floor-to-ceiling windows and the views of the lush backyard and the wooded canyon beyond it.

From the roof’s peak, the walls drop straight down, creating a more restrained entrance to the kitchen and its eating area. The kitchen has been modernised since Cooper’s time, buy much of the original aesthetic remains. New lighting recessed in long and narrow lines in the ceiling mimic Jones’ original straight lines, running perpendicular to the room-wide band of skylights that lets even more light flood in. Newson provides a breakfast seating area that, again, fades away through the wall of windows and sliding glass doors leading out to the backyard.

An outside stone fireplace was added to the patio in a recent minor renovation – of which there have been several in the home’s lifetime. The effect is an even more overt statement of inside-outness, adding another area where the lines between them are blurred. A few steps beyond is the swimming pool, flanked by a bar and barbecue for outdoor entertaining, in addition to a poolside pizza oven.

12 lamps by Jorge Pardo hang in the outdoor dining area.

The pool and much of the house is surrounded by grass and ringed with a half dozen of what can only appropriately be called LA palm trees. A wooden deck hangs over the slop of a slight crevice, rising above the canopy of pines, redwoods and oaks that provide the house with a verdant privacy screen. The previous owner created a more dramatic, sweeping drive into the property by buying and tearing down a couple of neighbouring houses – one of which was the former home of Barbra Streisand. From the street, all one can see is an array of dense hedges, eight feet tall. Beyond these green walls are all those tiny universes, spinning and twinkling on their own, only coming within each other’s orbit through the tinted windows of cars that pass each other by.

This understated aura of seclusion creates the conditions for the house and garden to overlap so well. Long before the advent of drone-flying paparazzi and the 24-hour celebrity gossip news cycle, Jones’ design demonstrated how to blend architecture with intimate spaces of outdoor respite. Each bedroom has its own secluded courtyard, shaded and separated from each other and the rest of the grounds. The master bedroom comes with an outdoor Jacuzzi, shielded from the rest of the yard and the pool by a boxing ring of leafy tropical plants.

Inside, there is a sizeable bathroom, with multiple marble showers and a bathtub sitting right next to expansive windows overlooking the garden. As in the other bathrooms, the exposure could seem vulnerable, but instead comes off as serene and protected thanks to the lush planting outside. A steam room and sauna area make up perhaps the darkest and most private space in a house that feels at times like a museum (albeit one on view only for the eucalyptus trees and century plants growing throughout the grounds).

Much of Jones’ original design works as well now as it worked in the 1950s. The variety of owners over the years have brought their own sensibilities to the house. Some moved walls or expanded spaces. The original asphalt driveway directly in front of the house was replaced with a stone walkway. A poolside bathroom and outdoor shower are also recent additions. The current owner stripped and stained the wood beams and roof panelling, which were originally painted white. The contrast now against the white plaster and white rocks is far more striking than the earlier iterations of the home as seen in old photographs of it. And yet, for all the changes, the home largely remains the same in spirit. It’s a prime example of elegant West Coast midcentury modernism that’s undeniably of its time, but also relevant today. §

As originally featured in the January 2013 issue of Wallpaper* (W*166)

Murakami's Dream Lion and Jeff Koon's Landscape (Waterfall) in the main dining room

The living room, with John Chamberlain's Superjuke sculpture, and Ed Ruscha's Psycho Spaghetti Western 9 on the wall. The ceiling is sloped, as in many Jones houses

The all-white master dressing room, with a Marc Newson chair in the centre

The kitchen, with a Joan Mitchell painting being moved

The master bedroom, with, from left, Yellow Butterfly by Mark Grotjahn on wall, a 'Random Pak' armchair and silver surfboard by Marc Newson; and Two Kellogg's Cornflakes Boxes (1964), by Andy Warhol. On the TV screen is the house's original owner, Gary Cooper, in High Noon

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

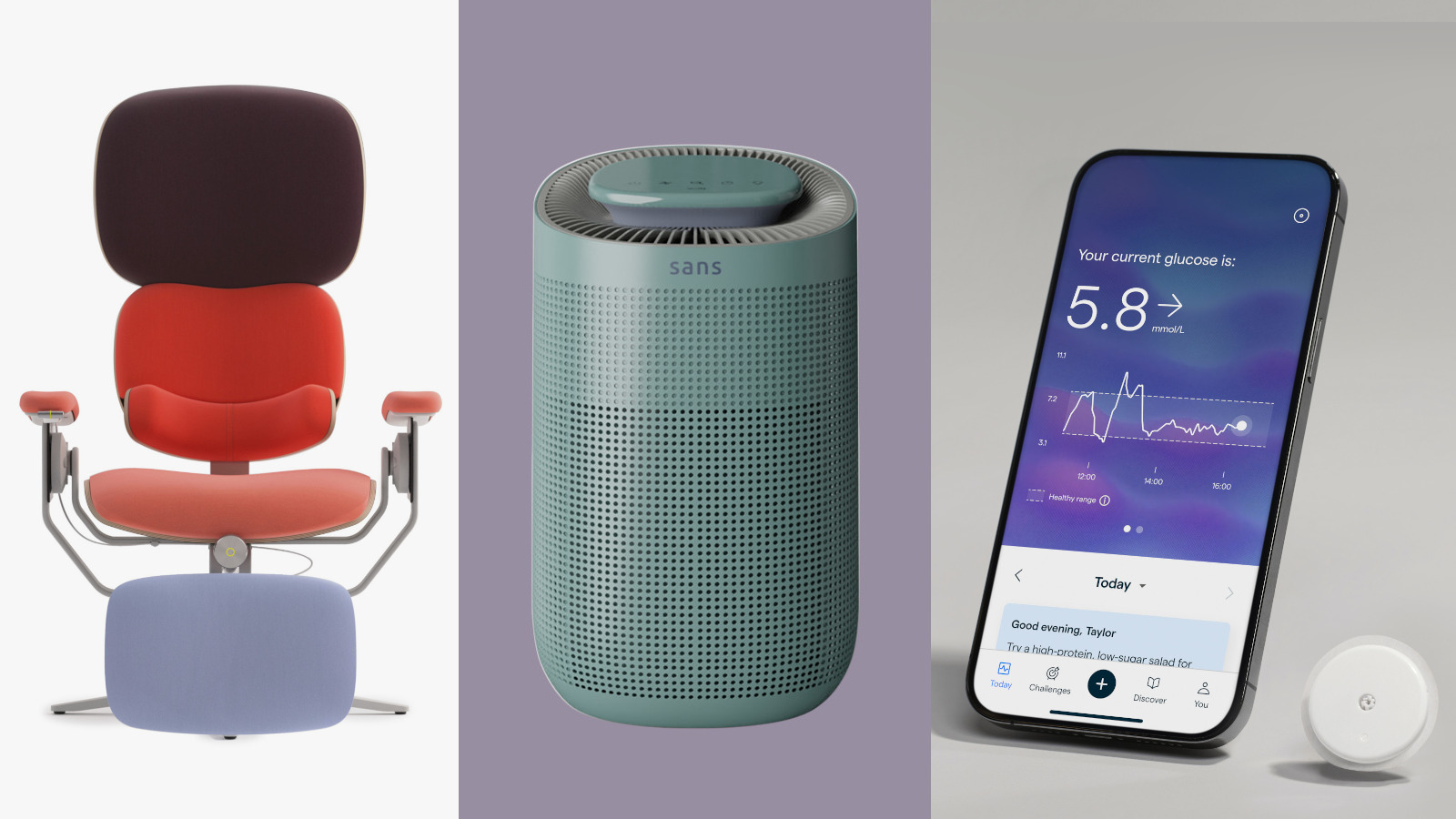

New tech dedicated to home health, personal wellness and mapping your metrics

New tech dedicated to home health, personal wellness and mapping your metricsWe round up the latest offerings in the smart health scene, from trackers for every conceivable metric from sugar to sleep, through to therapeutic furniture and ultra intelligent toothbrushes

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

How Stephen Burks Man Made is bringing the story of a centuries-old African textile to an entirely new audience

How Stephen Burks Man Made is bringing the story of a centuries-old African textile to an entirely new audienceAfter researching the time-honoured craft of Kuba cloth, designers Stephen Burks and Malika Leiper have teamed up with Italian company Alpi on a dynamic new product

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom wineries-turned-music studios to fire-resistant holiday homes, these are the properties that have most impressed the Wallpaper* editors this month

-

The Stahl House – an icon of mid-century modernism – is for sale in Los Angeles

The Stahl House – an icon of mid-century modernism – is for sale in Los AngelesAfter 65 years in the hands of the same family, the home, also known as Case Study House #22, has been listed for $25 million

-

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the market

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the marketAndré Wogenscky was a long-time collaborator and chief assistant of Le Corbusier; he built this home, a case study for post-war modernism, in 1957

-

Louis Kahn, the modernist architect and the man behind the myth

Louis Kahn, the modernist architect and the man behind the mythWe chart the life and work of Louis Kahn, one of the 20th century’s most prominent modernists and a revered professional; yet his personal life meant he was also an architectural enigma

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom Malibu beach pads to cosy cabins blanketed in snow, Wallpaper* has featured some incredible homes this month. We profile our favourites below

-

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architecture

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architectureWe visit three Danish modernist houses with writer, curator and architecture historian Adam Štěch, a delve into lower-profile examples of the country’s rich 20th-century legacy

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthThis September, Wallpaper highlighted a striking mix of architecture – from iconic modernist homes newly up for sale to the dramatic transformation of a crumbling Scottish cottage. These are the projects that caught our eye

-

Richard Neutra's Case Study House #20, an icon of Californian modernism, is for sale

Richard Neutra's Case Study House #20, an icon of Californian modernism, is for salePerched high up in the Pacific Palisades, a 1948 house designed by Richard Neutra for Dr Bailey is back on the market