How Le Corbusier defined modernism

Le Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

Le Corbusier defined modernism like no other architect. Part of a handful of masters of the 20th century midcentury style who made an indelible mark in modernist architecture - Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, Lina Bo Bardi and Alvar Aalto are some of the others – Le Corbusier is a leading figure in this most famous of architecture movements, and according to some, the first 'starchitect.'

Le Corbusier wrote, if not 'the', then 'a' rulebook for modernism – quite literally, as his groundbreaking 1923 book Towards a New Architecture famously outlined his 'five points of architecture', essentially the five elements a building should tick off if it wanted to be part of the brave new world of modernism (though others offered different interpretations, within the same movement). He was no stranger to controversy either, for example, painting murals on Eileen Gray's white-walled E-1027 house without her permission. A fascinating and complex figure, Le Corbusier has long captivated the architecture world, his influence spilling over to art, product, fashion and other creative industries. Scroll down, to explore the architect's life and work.

French architect and painter Le Corbusier at his studio, France 1960s

Who was Le Corbusier?

Le Corbusier was born in Switzerland's Jura region in 1887, named Charles-Édouard Jeanneret – and died during his daily swim (having suffered a heart attack) in his beloved seaside spot in the Cote d'Azur in 1965, aged 77.

Growing up in the Swiss heartland of watchmaking, young Le Corbusier started training in crafts and in particular, enamelling and engraving, at the age of 13. He went on to discover architecture with the encouragement of his teachers. A self-taught architect, he studied art history and drawing and followed the styles of his time, in particular Art Nouveau. He also travelled extensively in Europe, which started informing his understanding of architecture.

Early work, most done in his home country of Switzerland in collaboration with local architects, includes the Art Nouveaux-inspired Villa Fallet (1905–07, co-created during his studies there) and the more Art Deco volumes of Villa Schwob (1916–17), both in La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Living in Paris from the age of 30, he became familiar with the cutting-edge art movements of his time – such as abstraction and cubism. It was around that time that he started using his pseudonym, Le Corbusier – French for 'the crowlike one' but also a version of his grandfather's surname Lecorbésier. His work was influenced by his cultural encounters (eventually adopting the geometric, minimalist volumes his mature work is most well-known for) and he painted too.

Le Corbusier's five points of architecture

His designs were accompanied by studies and writing, as Le Corbusier authored several books over the decades. He proposed theoretical models, such as Dom-Ino House, an open-plan frame for a house, which outlined a system of planes, columns and stairs connecting levels, which could be customised and used as a base for several designs. It became a foundational model for his later works.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

He also collaborated with artists and poets of his time, such as purist painter Amédée Ozenfant and poet Paul Dermée, and even founded a magazine with the two, the avant-garde L’Esprit nouveau in 1920. Arguably one of his most influential publications was Vers Une Architecture – translated to Towards a New Architecture and first published in 1923.

Chandigarh's Capitol Building in India - as part of ‘Celebrating the Capitol’, an exhibition of photographic work by architect Noor Dasmesh Singh

A collection of essays, some of which had appeared in some form in L’Esprit nouveau, the book became a seminal reference for modernists, and architects, around the world during the 20th century. Within it, Le Corbusier outlined the five key elements that he felt were revolutionising the architecture of his time - and defined a modern, progressive home. These included: the use of pilotis (columns raising the building's main body off the ground), free-form, open-plan layouts, a facade design that is free from grids and symmetry, horizontal strip windows, and terraces and accessible roof gardens.

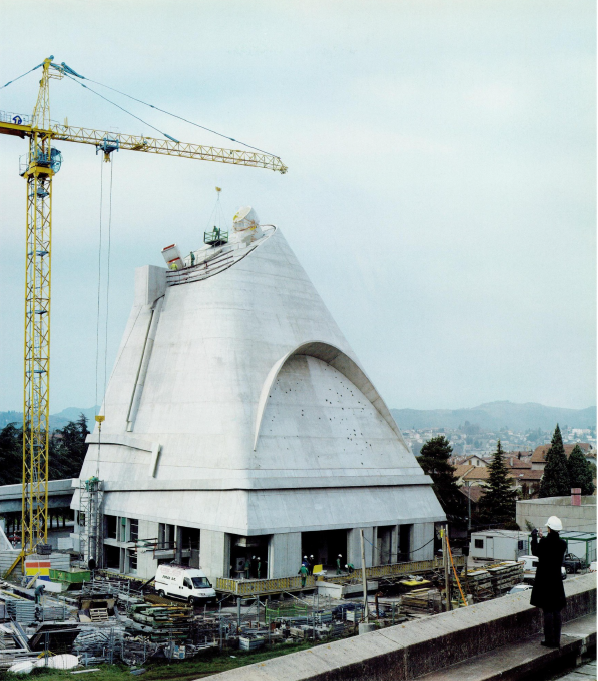

Church at Firminy by Le Corbusier, during construction in 2005

Le Corbusier: the first period (1922-1940)

Le Corbusier partnered with his cousin Pierre Jeaneret to found a joint practice in 1922. Defined by more traditional forms, these early works are a distinct period in the architect's career, lasting till 1940 when life and work across the globe were disrupted by the Second World War. Examples of this time's output include lots of designs for urban planning, unbuilt works and shows. It also spans some of the architect's most well-known designs and his extensive, early collection of single-family homes.

Works of that era include instantly recognisable oeuvres, such as the Ozenfant House and Atelier in Paris (1922-24), Maison Cook in Boulogne-Billancourt (1926), Villa Baizeau in Carthage, Tunisia (1928), and Villa Savoye in Poissy (1928-31). Their white volumes, radical for their time appearance, and forms largely following the 'five points' are seminal in Le Corbusier's growing portfolio - and key examples of 20th-century architecture across history books.

Villa Baizeau, Tunisia

Le Corbusier: the second period (1944-1965)

After the war ended, Le Corbusier's career took off, his portfolio becoming filled with landmark examples of 20th-century modernism, informed by his research and experimentations on what the modern city and the cities of the future could, and should, look like. His style started evolving too, from the clean, white, even serene shapes of his earlier houses to more bold, brutalist and austere forms.

The apartment block "Unite d'Habitation" by Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, is seen in West Berlin, on April 8, 2024

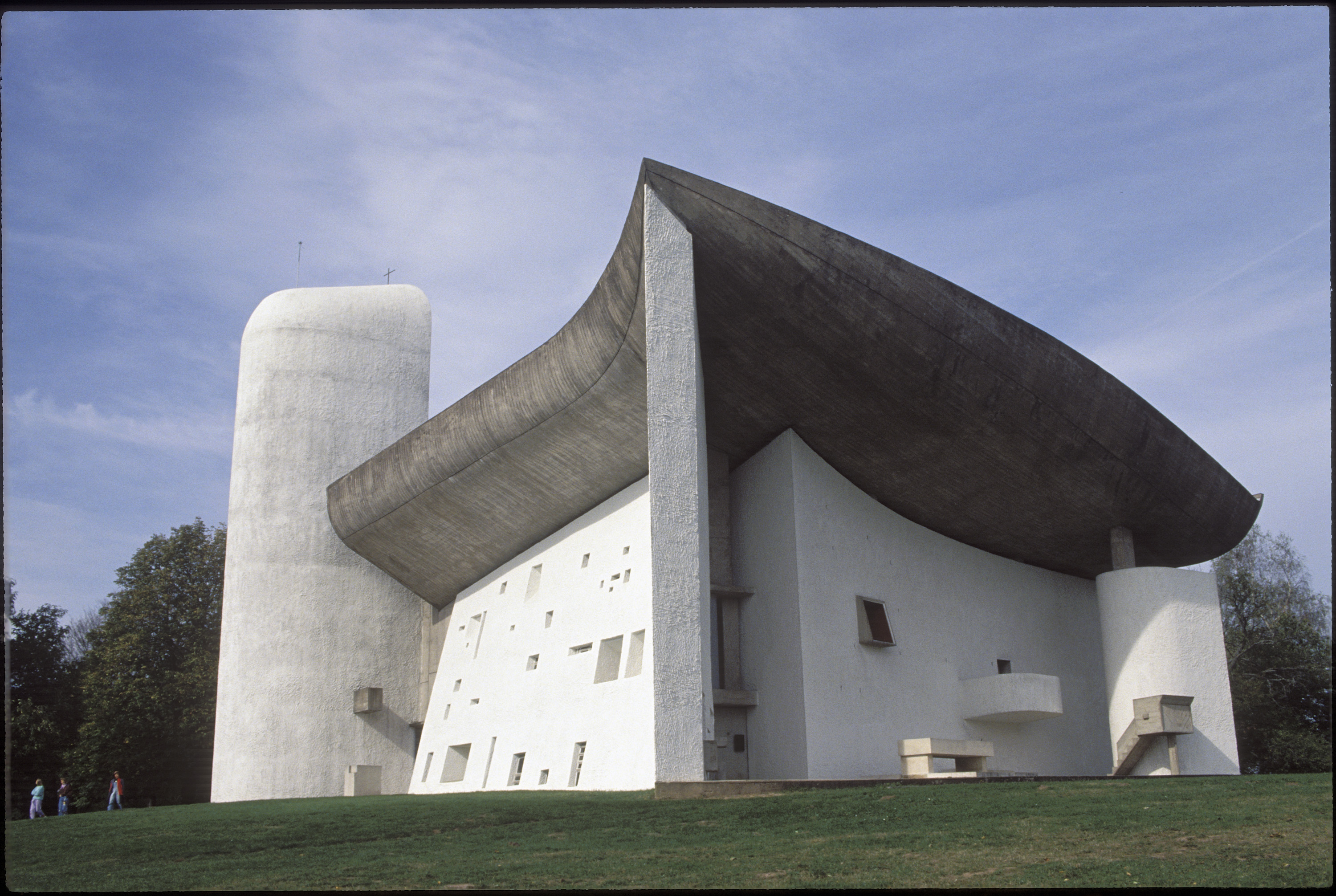

His second-period portfolio offers a star-studded tour of his most famous works. Examples include Marseille's Unite d'Habitation (1945-52), a case study of urban, high-density, self-contained social housing filled with amenities for its residents (which birthed several more examples in other places), to the Notre-Dame du Haut chapel (1950-55) in Ronchamp; his extensive work on the city of Chandigarh, India (1950-65), which involved many more architects and specialists in a group he led; the millowners' association in Ahmedabad (1951); the experimental Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels Expo; and his Église Saint-Pierre in Firminy, which was completed in 2006, 41 years after his death.

Pilgrimage church "Notre-Dame-du-Haut", Ronchamp 1990

Le Corbusier: controversies, legacy and death

Le Corbusier has been a polarising figure in the field. He has been criticised for unapologetically ignoring the local context in his building designs, and for creating urban visions that felt 'inhuman' and too austere. His political opinions have also been controversial, as alleged in a 2015 book by Xavier de Jarcy, 'Le Corbusier: A French Fascism.'

At the same time, according to the Le Corbusier Foundation in Paris, the architect was truly prolific, having 'built 79 buildings between 1905 and 1965 all over the world: in France, India and Switzerland, but also Germany, Belgium, Argentina, Japan, Russia, Tunisia and the United States.' His legacy has been multifold, spanning building design and urban planning, ushering ideas for 20th-century architecture that were novel and revolutionary.

The 'Open Hand', seen here in the Capitol complex in Chandigarh, is a recurring artistic motif in his work

His work, throughout his career, has also included furniture design (often created in collaboration with partners, such as Pierre Jeaneret and Charlotte Perriand), painting, sculpture and crafts, such as enamelling and engraving. 'It is in the practice of plastic arts that I found the intellectual sap of my urbanism and my architecture,' he has said, as mentioned in the foundation's archives on his artworks.

Le Corbusier had a small, modest wooden cabin in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, built in 1951, which he often visited. 'I have a stately home on the French Riviera, 3.66m by 3.66m. It’s for my wife, a prodigality of comfort and kindness,' he has said of his retreat. He died there while swimming off the coast of the French Riviera in 1965.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Ligne Roset teams up with Origine to create an ultra-limited-edition bike

Ligne Roset teams up with Origine to create an ultra-limited-edition bikeThe Ligne Roset x Origine bike marks the first venture from this collaboration between two major French manufacturers, each a leader in its field

By Jonathan Bell

-

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive design

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive designIt’s not exactly king of the crossovers, but the Subaru Forester e-Boxer is reliable, practical and great for keeping a low profile

By Jonathan Bell

-

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 million

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 millionThe architect's ‘Double-Pedestal’ lamp, which was designed for the Dana House in 1903, is hitting the auction block 13 May at Sotheby's.

By Anna Solomon

-

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yoursJean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

By Amy Serafin

-

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, UzbekistanThe legacy of modernist architecture in Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent, is explored through research, a new publication, and the country's upcoming pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; here, we take a tour of its riches

By Will Jennings

-

This ‘architourism’ trip explores India’s architectural history, from Mughal to modernism

This ‘architourism’ trip explores India’s architectural history, from Mughal to modernismArchitourian is offering travellers a seven-night exploration of northern India’s architectural marvels, including Chandigarh, the city designed by Le Corbusier

By Anna Solomon

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

By Ellie Stathaki

-

How to protect our modernist legacy

How to protect our modernist legacyWe explore the legacy of modernism as a series of midcentury gems thrive, keeping the vision alive and adapting to the future

By Ellie Stathaki

-

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st Century

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st CenturyThanks to a sensitive redesign by Studio Hagen Hall, this midcentury gem in Hampstead is now a sustainable powerhouse.

By Ellie Stathaki

-

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tall

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tallMuseu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP) expands with a project named after Pietro Maria Bardi (the institution's first director), designed by Metro Architects

By Daniel Scheffler

-

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in France

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in FranceFondation Marta Pan – André Wogenscky: how a creative couple’s sculptural masterpiece in France keeps its authors’ legacy alive

By Adam Štěch