Modernist churches: we give praise for the genre’s concrete geometries

Modernist churches offer awe and architectural inspiration, blending concrete geometries with spiritual reverence; we take a tour

You don't need to subscribe to spirituality to admire the spectacle modernist churches have to offer. The spatial gymnastics and fantastical geometries of many post-war ecclesiastical structures are inspirational, offering striking visuals and architecture that was cutting-edge for its time. Creating a genre in its own right, the modernist architecture of religious buildings became a playground for architects to experiment and express themselves throughout the 20th century – in Europe and beyond.

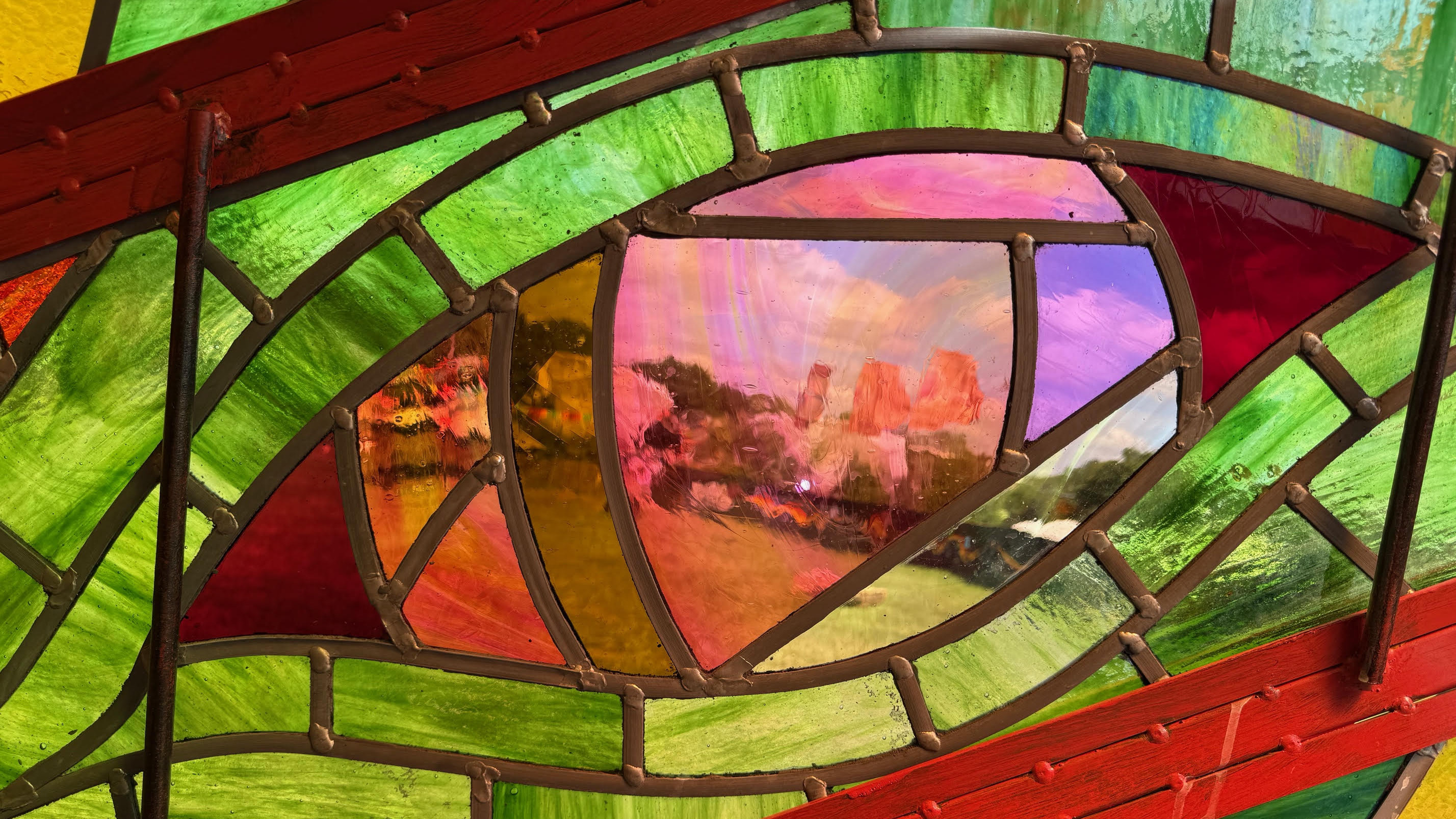

Image of L'Eglise Saint Nicolas by Walter Maria Forderer in Switzerland, from the book Sacred Modernity: The Holy Embrace of Modernist Architecture by Jamie McGregor Smith for publisher Hatje Cantz

Modernist churches: six of the world's finest examples

Many creatives have been drawn to modernist churches, captivated by their vision, structural feats and bold design. Photographer (and Wallpaper* contributor) Jamie McGregor Smith is one of them, recently revealing his personal journey across post-war modernism through a series of worn and weathered structures captured through his lens for a book titled Sacred Modernity: The Holy Embrace of Modernist Architecture, published by Hatje Cantz.

At Wallpaper*, we have also long been partial to the genre, having featured numerous case studies representing the typology over the years. From the brutalist forms of Julian Lampens' work in Belgium to Walter Maria Förderer's mesmerising compositions, we have gathered six striking examples to enjoy. Scroll down for more.

Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare by Julian Lampens, Belgium

Belgian modernist Julien Lampens' commission for the Chapel of Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare followed soon after the completion of his own house in 1960. However, the design with which he won the 1961 competition – with Professor Rutger Langaskens, one of his former teachers – was very different from what you see today. Upon winning, Lampens reworked the building, making it so altered from the original and so alien to the neighbourhood that during the concrete casting, passers-by thought it would be a silo. Despite this, and with the incumbent pastor's support, the high-ceilinged chapel – resembling a giant concrete skip – opened in 1966.

It featured bespoke concrete benches (currently removed), a large glass wall and a central concrete skylight, while the protruding mono-pitched roof provided outdoor shelter for the congregation. It was the chapel's large untreated surfaces that led many to label Lampens a follower of brutalist architecture, a tag he has never accepted. The chapel and his Eke house were landmarks in Lampens' career.

Pilgrimage Church by Gottfried Böhm, Germany

Born in 1920, the son of acclaimed architect Dominicus Böhm, Gottfried Böhm began his career combining architecture and sculpture at the Technical University Munich and the Academy of Fine Arts. His finished works include more than 40 churches, from Taiwan to Brazil. The Pilgrimage Church project began as a competition-winning entry in 1964, in response to the Catholic archdiocese of Koln's call for a church in Neviges, a small town about half an hour outside the city.

Böhm's winning design ticked all the boxes, providing both the space and atmosphere for religious functions – it offers seating for 800 and standing room for 2,200 in a truly spectacular building – without any obvious recourse to traditional religious symbolism. The church was completed in May 1968 and instantly became a landmark in the town. Taking advantage of a row of pilgrims' houses and the church's position at the top of a slope, Böhm created a processional way leading up the hill, into the church's open courtyard and inside, ending at the altar and the pilgrimage's religious climax.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Church of Santa Maria Immacolata by Giovanni Michelucci

Comprising a pair of intersecting and spiralling concrete amphitheatres – one internal, the other external – the Church of Santa Maria Immacolata, consecrated in 1983, is a late-flowering masterwork by Italian architect Giovanni Michelucci, who died in 1990 at the age of 99. Commissioned in 1966, Santa Maria Immacolata is both a parish church and a memorial to the 1,450 citizens of Longarone killed on the night of 9 October 1963 by a megatsunami caused by a landslide crashing into the nearby Vajont Dam, triggering a 250m-high wave that engulfed the town.

Santa Maria Immacolata is sombre and haunting, a journey of the soul up to the mountains and down again along an enigmatic architectural path. Its sinuous copper roof covers the asymmetric, stone-clad concrete building like the folds of a Biblical tent, while the columns supporting the roof form a mesmerising architectural grove.

First Christian Church by Eliel and Eero Saarinen, USA

First Christian Church, designed by Eliel and Eero Saarinen and completed in 1942, is widely considered to be the first modernist architecture church in the United States. Designated a national Historic Landmark in 2000, the structure features a tower that soars six levels above ground, and also includes a basement and a cistern in a sub-basement. Its walls are entirely constructed of brick – 29 inches thick at the base, tapering to 17 inches thick at the top.

A recent renovation stabilised and repaired its tower’s Clock Chamber levels, removing the east and west walls, along with the removal of brick veneer on the north and south faces, and the dismantling of the parapets. The east and west sides were then reconstructed with a concrete block back-up for stability. The plastic which had replaced the tower’s original precast concrete grilles was substituted with Indiana limestone, carved in the original patterns to simulate the appearance of the tower’s period concrete construction – but with much-enhanced durability.

L'Eglise Saint Nicolas by Walter Maria Förderer, Switzerland

Walter Maria Förderer, born in 1928, was at the forefront of the generation of Swiss architects to practise in the late 1940s and 1950s. He began his career as a sculptor, and his use of concrete evolved from his preference for the hands-on contact with a material. By the time he was in his forties, Förderer had become an inspiration to Swiss architects, spawning a fashion for expressive concrete schemes which threatened to usurp even Le Corbusier’s achievements in the field. His design for the L'Eglise Saint Nicolas is sculptural and imposing.

Clifton Cathedral by Percy Thomas Partnership, UK

Architecture buffs might recognise the brutalist Clifton Cathedral in Bristol by its distinctive, irregular, elongated hexagonal floorplan. Architecture and heritage experts Purcell were behind a recent, careful repair work to the building’s historical fabric, rendering the cathedral fully watertight for the first time ever. The structure, also known as the Roman Catholic Cathedral Church of SS Peter and Paul in Clifton, Bristol, was originally constructed between 1969-73 to a design by Ron Weeks of the Percy Thomas Partnership and is a Grade II*-listed monument.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

A bespoke 40m mixed-media dragon is the centrepiece of Glastonbury’s new chill-out area

A bespoke 40m mixed-media dragon is the centrepiece of Glastonbury’s new chill-out areaNew for 2025 is Dragon's Tail – a space to offer some calm within Glastonbury’s late-night area with artwork by Edgar Phillips at its heart

-

‘100 Years, 60 Designers, 1 Future’: 1882 Ltd plate auction supports ceramic craft

‘100 Years, 60 Designers, 1 Future’: 1882 Ltd plate auction supports ceramic craftThe ceramics brand’s founder Emily Johnson asked 60 artists, designers, musicians and architects – from John Pawson to Robbie Williams – to design plates, which will be auctioned to fund the next generation of craftspeople

-

Jonathan Anderson’s Dior debut: ‘bringing joy to the art of dressing’

Jonathan Anderson’s Dior debut: ‘bringing joy to the art of dressing’The Irish designer made his much-anticipated debut at Dior this afternoon, presenting a youthful S/S 2026 menswear collection that reworked formal dress codes

-

Eileen Gray: A guide to the pioneering modernist’s life and work

Eileen Gray: A guide to the pioneering modernist’s life and workGray forever shaped the course of design and architecture. Here's everything to know about her inspiring career

-

Discover Canadian modernist Daniel Evan White’s pitch-perfect homes

Discover Canadian modernist Daniel Evan White’s pitch-perfect homesCanadian architect Daniel Evan White (1933-2012) had a gift for using the landscape to create extraordinary homes; revisit his story in an article from the Wallpaper* archives (first published in 2011)

-

A night at Pierre Jeanneret’s house, Chandigarh’s best-kept secret

A night at Pierre Jeanneret’s house, Chandigarh’s best-kept secretPierre Jeanneret’s house in Chandigarh is a modernist monument, an important museum of architectural history, and a gem hidden in plain sight; architect, photographer and writer Nipun Prabhakar spent the night and reported back

-

Lina Bo Bardi, the misunderstood modernist, and her influential architecture

Lina Bo Bardi, the misunderstood modernist, and her influential architectureA sense of mystery clings to Lina Bo Bardi, a modernist who defined 20th-century Brazilian architecture, making waves still felt in her field; here, we explore her work and lasting influence

-

Oscar Niemeyer: a guide to the Brazilian modernist, from big hits to lesser-known gems

Oscar Niemeyer: a guide to the Brazilian modernist, from big hits to lesser-known gemsArchitecture master Oscar Niemeyer defined 20th-century architecture and is synonymous with Brazilian modernism; our ultimate guide explores his work, from lesser-known schemes to his big hits; and we revisit a check-in with the man himself

-

Modernist Travel Guide: a handy companion to explore modernism across the globe

Modernist Travel Guide: a handy companion to explore modernism across the globe‘Modernist Travel Guide’, a handy new pocket-sized book for travel lovers and modernist architecture fans, comes courtesy of Wallpaper* contributor Adam Štěch and his passion for modernism

-

Discover architect Ico Parisi’s modernist sanctuaries on the banks of Lake Como

Discover architect Ico Parisi’s modernist sanctuaries on the banks of Lake ComoA string of sculptural sanctuaries by architect Ico Parisi on the banks of Lake Como helped cement the area as the heartland of Italian modernism; we explore his work in an article from the Wallpaper* archives

-

Ukrainian Modernism: a timely but bittersweet survey of the country’s best modern buildings

Ukrainian Modernism: a timely but bittersweet survey of the country’s best modern buildingsNew book ‘Ukrainian Modernism’ captures the country's vanishing modernist architecture, besieged by bombs, big business and the desire for a break with the past