Inside Europe's modernist estates and their distinct cultures

Stefi Orazi welcomes readers inside her book Modernist Estates Europe, where she speaks to residents about daily life inside these 20th-century domestic experiments

Modernist Estates Europe builds a humanist portrait of life at 15 residential housing estates across the continent. Author Stefi Orazi, a graphic designer by trade, compiles short architectural histories of the estates alongside photography and intereviews with residents.

The project began when Orazi was looking for a place to live in London. She started a blog of photographs and information on London housing estates, and soon discovered a passion that many others shared. In 2015, she published Modernist Estates, a book that brought her blog into print. In 2016, with the Brexit referendum looming, Orazi decided to look slightly further afield, wondering how people outside London perceived modern estates.

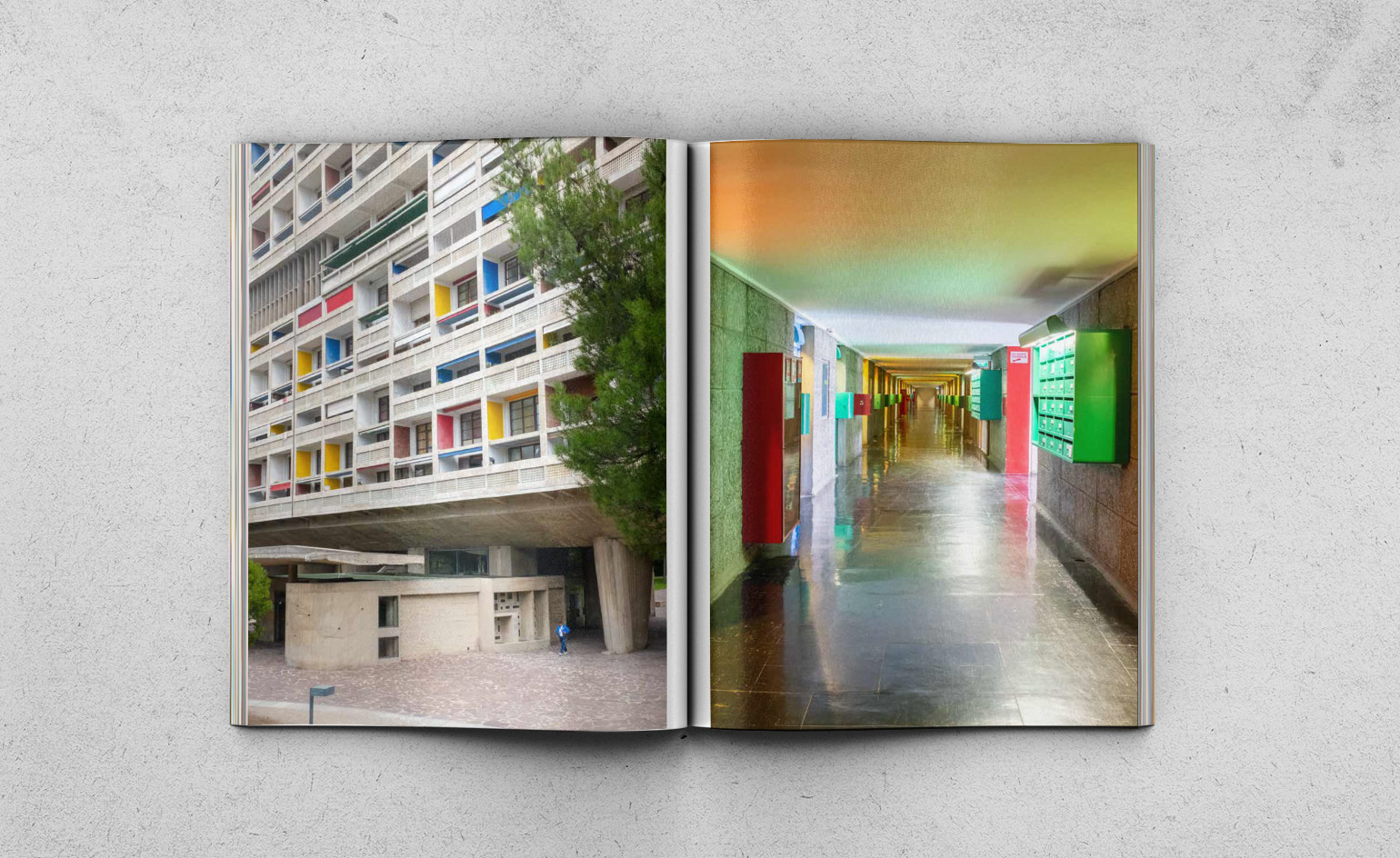

The exterior and interior corridor at Cité Radieuse featured in the book

‘While Britain spent the next two years wrangling on how to withdraw itself from the EU, I spent it feeling grateful that I could travel from one country to the next, reflecting on how that freedom also allowed many of the architects featured in this book to share ideas across country borders,’ she writes of the period of time during which she was conducting her research for the book.

Each project is located in ‘Europe’ culturally, with Switzerland being a political and economic exception. The projects span almost a century with the earliest estate Bellevue by Arne Jacobsen built in the 1930s, and the latest Neave Brown estate in Eindhoven, the Medina, completing in 2007. While each is ‘modernist' in its functionality and philosophy, each offers a profoundly new approach to living and each have their own priorities. Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse, built in 1952 provided a template for modernity, starting a conversations across architectural circles, yet each estate appears to lift ideas and design elements in new ways.

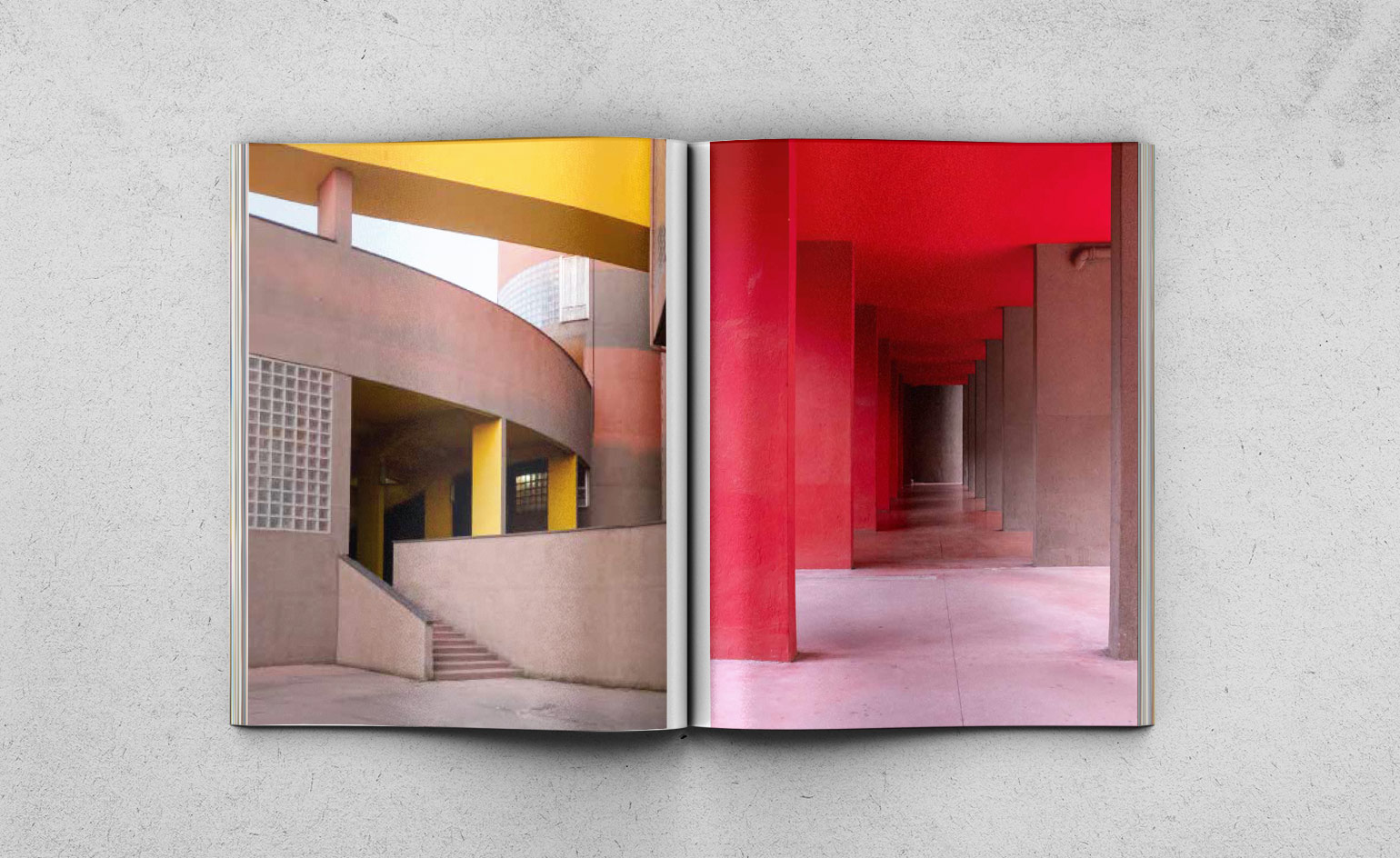

Monte Amiata, Gallaratese II, Milan, Italy – designed by Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi

Plans and developments of the estates connect in different ways. Some are low rise sprawls, others high rise mountains. In Sweden, the free-standing ‘point block’ development became popular, meanwhile in Marseilles the Cité Radieuse set the standards for the all-enveloping block style. In Germany, the Deutscher Werkbund were ‘typically white sugar cube like houses with flat roofs that became synonymous with the modern movement,’ writes Orazi.

While many estates share common ground. Most of the estates Orazi has chosen are positioned just outside cities, where there was space to build bigger developments with grand ambitions. This allowed them to have a strong connection to nature through location or design. The Siedlung Halen in Bern looks like it has been dropped into a forest; the Danviksklippan in Stockholm is positioned on a rocky plot by the coast; while the Ivry-sur-Seine in Paris’ suburbs, designed by architect Jean Renaudie, is layered with overflowing terraces of triangular gardens; and Walden 7 in Barcelona is surrounded by gardens of eucalyptus, palms, olive trees and cypresses.

Walden 7, Barcelona, Spain – designed by Ricardo Bofill, Taller de Arquitectura

Meeting the residents was the best way for Orazi to gain an insight into daily life at her estate case studies. Modernist Estates is subtitled ‘the buildings and the people who live in them today’, because the book is very much about the people who live there. Orazi was welcomed into living rooms with comfy looking sofas, bedrooms with colourful curtains, kitchens with collections of utensils and pot plants, as people told their stories of life on a modernist estate.

For many people, living on their modernist estate is hereditary – a credit to the architecture and lifestyle. Mads Hage Thomsen grew up at Copenhagen’s Bellevue designed by Arne Jacobsen in the 1970s and now lives there with his own family. Karin Büchler’s parents bought her home in 1969, and she and her family moved back in 2013. Meanwhile the Monte Amiata in Milan has inspired resident Serene Cazzulani’s 12-year-old son to want to become an architect.

There’s a strong link between the buildings and the living experience – it’s full of crazy people!

Younes Karroum, Walden 7 resident

Many of the estates were built to encourage community living, yet Orazi’s reports show that the facilities are often left redundant – the theatre at the Monte Amiata lies empty and the shops at Danviksklippan have closed down due to improved transport links and delivery services. ‘The newer generation don’t really get the original utopian concept’, says Elisabeth Huttier, resident at Ivry-sur-Seine, where she has lived for 46 years and seen dramatic changes in community life.

The colourful architecture of Monte Amiata featured in the book

On the other hand, there are still many signs that the 21st-century communities are very much alive. In Marseille at the Cité Radieuse, resident Artemis Kosta enjoys the relationships she has with other parents: ‘It’s like a village here’, she says. There’s a school on the 8th floor, and all the neighbours with young children help each other out by picking up the kids after school and dropping them home. Karin Buchler, another mother, resident at Siedlung Halen has a similar experience: ‘Everybody’s door is open here, kids go from house to house – they are living with pretty much ten different families,’ she says.

Whilst many residents seem to adore living in these places, they also have their gripes. At Walden 7, the light is poor due to small windows. At Siedlung Halen the roof replacement project was put on hold because not everyone has the money to contribute, and the electrical and heating systems are becoming old. Fredrik Jansson, Danvikslippan resident, describes an unfortunate balcony replacement involving a jackhammer: ‘It needs repairing all the time!’

Ivry-sur-Seine, Paris, France – designed by Jean Renaudie

Many of the estates are protected, listed or even UNESCO historic monument in the case of the Cité Radieuse and many people pride themselves in returning their homes to original standards. Jose Pedro Croft, resident at Bloco das Aguas Livres, Lisbon, worked with the original architects to restore his apartment back to the original conditions after a period of questionable taste during previous ownership. Yet other residents don't share this passion. ‘We shouldn’t treat homes as if they are museums,’ says Barbara Göttlinger at the Werkbund-siedlung Austria, whose home was originally preserved to be a museum open to the public until the plan changed and it was designated for living. ‘We can’t even change the colours of the walls of the doors’, she says.

Mostly, Orazi seems to have discovered a culture of people who take pride in living to the ideals of modernism and celebrating the 20th-century architectural history. These estates are a bit like people as well – a friend who has equal parts flaws and unique personality traits that you couldn’t live without. Younes Karroum, Walden 7 resident, sees a link between the residents and the architecture: ‘There’s a strong link between the buildings and the living experience – it’s full of crazy people!’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Monte Amiata, Gallaratese II, Milan, Italy – designed by Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi

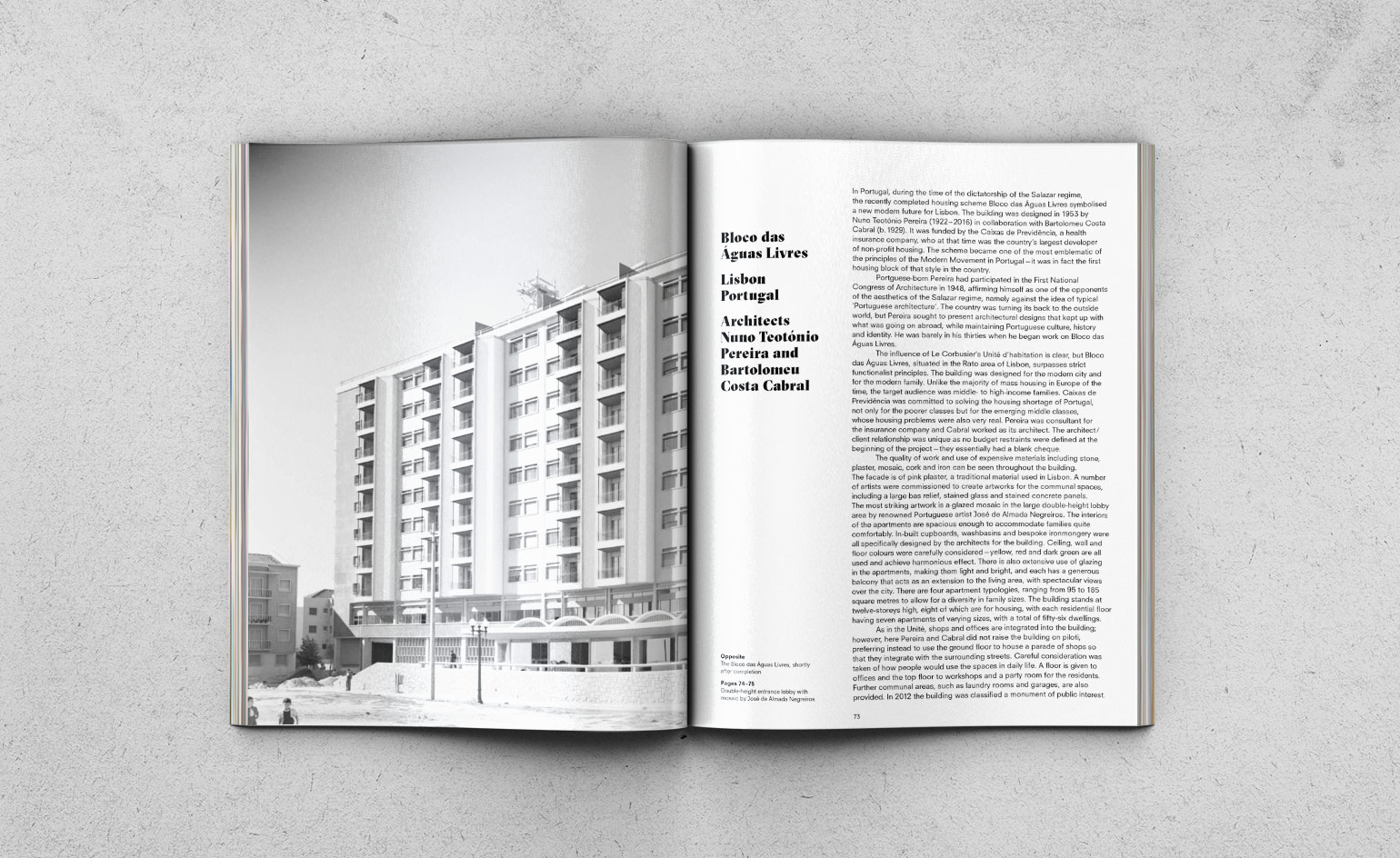

Interiors at Bloco das Águas Livres, featured in the book

Cité Radieuse, Marseille, France – designed by Le Corbusier

Each case study features a short architectural history, pictured here, Bloco das Águas Livres archive image

Calthorpe Estate, Edgbaston, Birmingham, England – designed by John Madin

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the White Lion Publishing website

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculptures

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculpturesThe Japanese designer creates an intuitive series of bold play sculptures, designed to spark children’s desire to play without thinking

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025At Milan Design Week 2025 Japanese craftsmanship was a front runner with an array of projects in the spotlight. Here are some of our highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yoursJean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

By Amy Serafin

-

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, UzbekistanThe legacy of modernist architecture in Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent, is explored through research, a new publication, and the country's upcoming pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; here, we take a tour of its riches

By Will Jennings

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

By Ellie Stathaki

-

How Le Corbusier defined modernism

How Le Corbusier defined modernismLe Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

By Ellie Stathaki

-

How to protect our modernist legacy

How to protect our modernist legacyWe explore the legacy of modernism as a series of midcentury gems thrive, keeping the vision alive and adapting to the future

By Ellie Stathaki

-

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st Century

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st CenturyThanks to a sensitive redesign by Studio Hagen Hall, this midcentury gem in Hampstead is now a sustainable powerhouse.

By Ellie Stathaki

-

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tall

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tallMuseu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP) expands with a project named after Pietro Maria Bardi (the institution's first director), designed by Metro Architects

By Daniel Scheffler

-

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in France

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in FranceFondation Marta Pan – André Wogenscky: how a creative couple’s sculptural masterpiece in France keeps its authors’ legacy alive

By Adam Štěch