The Modernist Glade: an urban garden pops up in Milton Keynes

The Modernist Glade, a temporary, architectural public commission by London studio Hayatsu Architects and Danish artist Tue Greenfort, opens to the public

Jamie Woodley - Photography

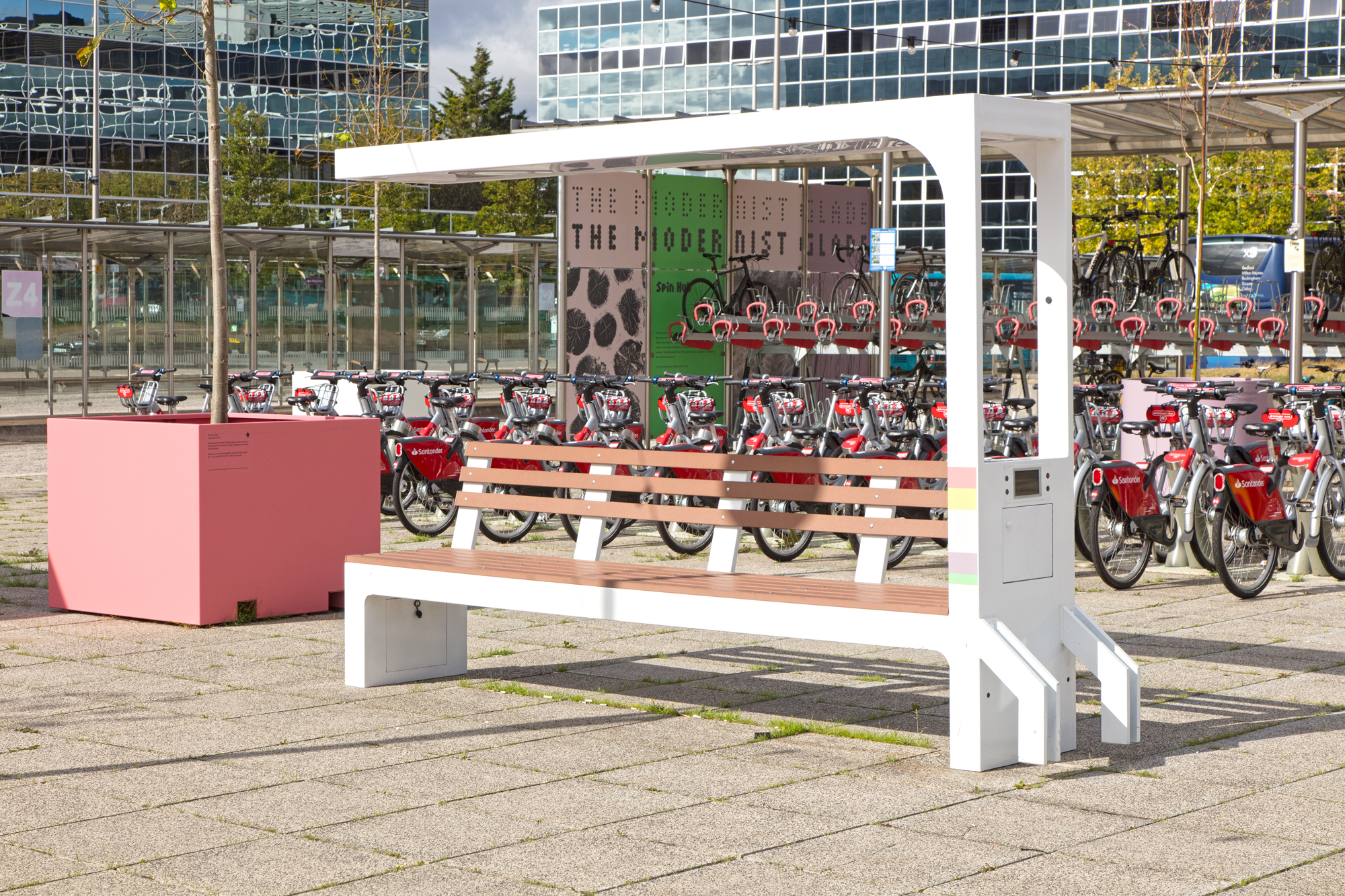

The first thing you see when you arrive in Milton Keynes by train is Station Square. Framed on three sides by long reflective glass buildings, this expansive plaza and transport hub had, until recently, lacked a sense of purpose, density or softness. Yet this is about to change, as a new installation titled The Modernist Glade – part temporary public art, part architectural pavilion project, and part experimental urban renewal intervention with a nod to sustainability – promises to subvert the idea of a glade and apply it to the city's heart in the shape of an urban garden.

‘[Station Square] is a very large, very open and also quite empty space,' says Takeshi Hayatsu, founding director of London-based Hayatsu Architects. He is one third of the team, who, alongside artist Tue Greenfort and curator and producer Aldo Rinaldi, was commissioned by Milton Keynes Council and Milton Keynes Development Corporation to revitalise this important but under-used urban space.

The architects soon realised that the key to making Station Square a place you want to spend time in was to create a series of smaller spaces within it and dedicate each one to different activities and ideas. They subdivided the square into a grid in which they placed 48 planters containing different types of tree at regular 10m intervals, installed four pavilions designed for different activities and functions, and reorganised existing street furniture to respect the new modular layout.

‘The idea of the grid was a reference to the radical grid the city was originally planned on back in the 1960s,’ says Hayatsu. ‘We asked ourselves how we could adapt it to the 21st century.' The answer was make nature the underlying theme – in this case trees, fungi and insects – and choose materials accordingly. ‘20th century modernism was pretty much about concrete and steel, so our Modernist Glade is full of timber, stone and recycled or natural materials.' The trees are also a nod to the utopian ideals of this ‘new’ city and the millions of trees planted upon its founding in 1967; a staggering 25 per cent of the city is now covered in trees, some 22 million in total.

The impact of this project is subtle, partly because the trees are young and starting to lose their leaves and not every element of the plan is completed or has bedded in. But early signs are promising and the intent and ambition is bold and pioneering. The main pavilion is a freestanding square structure with arresting mushroom bags hanging from the ceiling, a table resting on slim and knobbly tree branches, and a pleasing geometry to its wood architecture. The stretched canvas on the roof and walls (which can be removed to make the pavilion entirely open) bring to mind the paper used in Japanese shoji screens. The large stones that this and the other structures rest on are deceptive. They are arresting and beautiful in their own right but also anchor the structures in place with the help of hidden stainless steel dowels.

‘We see this pavilion as a laboratory where you can come together and make things,' says Greenfort, who has added a layer of ecological urgency and depth to the project, and is curating the two-year programme to activate the square. Workshops will be held on how to grow mushrooms or make baskets out of the willow harvested from the screens installed elsewhere, for example.

Two main lawns that were empty have been transformed too. Sections have been ‘rewilded’ so that the wild flowers, plants and fungi can attract bees and insects that are in steady decline. One lawn houses a timber screen and canopy for screenings, while the other will host a bee hive (the bees will enter the hive via a tactile ceramic flower with an opening where the stamens should be, also designed by Greenfort).

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Eventually, fungi will fill the tree planters and cover the locally sourced log seating that is dotted around the project too. The most interesting part of a fungus is not the umbrella-shaped ‘flower’ you see above ground, explains Greenfort, but the subterranean network of roots or mycelia that allow trees and fungus to communicate and exchange nutrients and chemicals. He likens this to an underground internet, but it has also been called the plant version of mutual aid.

It’s this symbiotic relationship that The Modernist Glade hopes to celebrate over the next two years, on the one hand exploring how we can cohabit with other species and live more sustainably alongside them in the urban world, but on the other, and on a more pragmatic level, testing ways the square can become a greener, more pleasant and liveable part of the city.

INFORMATION

Giovanna Dunmall is a freelance journalist based in London and West Wales who writes about architecture, culture, travel and design for international publications including The National, Wallpaper*, Azure, Detail, Damn, Conde Nast Traveller, AD India, Interior Design, Design Anthology and others. She also does editing, translation and copy writing work for architecture practices, design brands and cultural organisations.

-

Discover Locus and its ‘eco-localism' - an alternative way of thinking about architecture

Discover Locus and its ‘eco-localism' - an alternative way of thinking about architectureLocus, an architecture firm in Mexico City, has a portfolio of projects which share an attitude rather than an obvious visual language

-

MoMA celebrates African portraiture in a far-reaching exhibition

MoMA celebrates African portraiture in a far-reaching exhibitionIn 'Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination' at MoMA, New York, studies African creativity in photography in front of and behind the camera

-

How designer Hugo Toro turned Orient Express’ first hotel into a sleeper hit

How designer Hugo Toro turned Orient Express’ first hotel into a sleeper hitThe Orient Express pulls into Rome, paying homage to the golden age of travel in its first hotel, just footsteps from the Pantheon

-

Piet Oudolf is the world’s meadow-garden master: tour his most soul-soothing outdoor spaces

Piet Oudolf is the world’s meadow-garden master: tour his most soul-soothing outdoor spacesPiet Oudolf is one of the most impactful contemporary masters of landscape and garden design; explore our ultimate guide to his work

-

How Maggie’s is redefining cancer care through gardens designed for healing, soothing and liberating

How Maggie’s is redefining cancer care through gardens designed for healing, soothing and liberatingCancer support charity Maggie’s has worked with some of garden design’s most celebrated figures; as it turns 30 next year, advancing upon its goal of ‘30 centres by 30’, we look at the integral role Maggie’s gardens play in nurturing and supporting its users

-

A Chilean pavilion cuts a small yet dramatic figure in a snowy, forested site

A Chilean pavilion cuts a small yet dramatic figure in a snowy, forested siteArchitects Pezo von Ellrichshausen are behind this compact pavilion, its geometric, concrete volume set within a forest in Chile’s Yungay region

-

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna Doshi

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna DoshiDoshi Retreat opens at the Vitra campus, honouring the Indian modernist’s enduring legacy and joining the Swiss design company’s existing, fascinating collection of pavilions, displays and gardens

-

Honouring visionary landscape architect Kongjian Yu (1963-2025)

Honouring visionary landscape architect Kongjian Yu (1963-2025)Kongjian Yu, the renowned landscape architect and founder of Turenscape, has died; we honour the multi-award-winning creative’s life and work

-

‘Landscape architecture is the queen of science’: Emanuele Coccia in conversation with Bas Smets

‘Landscape architecture is the queen of science’: Emanuele Coccia in conversation with Bas SmetsItalian philosopher Emanuele Coccia meets Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets to discuss nature, cities and ‘biospheric thinking’

-

Explore the landscape of the future with Bas Smets

Explore the landscape of the future with Bas SmetsLandscape architect Bas Smets on the art, philosophy and science of his pioneering approach: ‘a site is not in a state of “being”, but in a constant state of “becoming”’

-

10 landscape architects to know now: the ultimate directory

10 landscape architects to know now: the ultimate directoryThe Wallpaper* 2025 Landscape Architects’ Directory spotlights the world's most exciting studios, each one transforming the environment around us with projects that celebrate nature in design