We tour Monaco’s Mareterra neighbourhood: where minimalist architecture and marine research meet

Mareterra, a contemporary enclave with designs by Renzo Piano offers homes, a new coastal promenade, a dynamic Alexander Calder sculpture and an atmospheric social hub extending the breezy, minimalist spirit of Larvotto Beach

Monaco is celebrating the opening of its new coastal neighbourhood named Mareterra, located between Larvotto Beach and the Fairmont Hairpin, first announced in 2013. The new eight-hectare enclave, which we visited while still under construction, is built upon a land extension and marked by its flagship super-prime residential building designed by Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW). There are other more humble, yet perhaps equally as powerful, highlights to discover: a generous new coastal pathway, the planting of over 1000 mature trees, and the return of a large outdoor Alexander Calder sculpture to the public realm.

Explore the new Monaco neighbourhood of Mareterra

The prominent Le Renzo certainly steals the spotlight as a welcomed characterful addition to the skyline. It rests on piloti above a stepped podium of public space, a small port lined with shops and restaurants (most yet to open) and the minimalist residents’ sea pool that absorbs the energy of the waves (a design first for RPBW, experts in coastal architecture). The building’s nautical volumes were ‘fragmented’ to frame views of the sea line from the city, says Erik Volz, associate and project director at RPBW who has been working at the firm for nearly 29 years.

Its elegant exoskeleton hosts three-metre-deep balconies with reflective glass ‘papillon’ panels, which together shade the building from the sun and dazzle any prying eyes. The spacious apartments (ranging from 400 to 1,900 sq m) all have both city and sea views, and the interiors (which haven’t been outsourced by off-plan buyers) are ‘very zen’ with white kitchens and oak flooring creating a ‘museum atmosphere’ to magnify the abundance of light, views and space, says Volz.

The rest of the development evokes a softer, blended and more ‘natural perspective’ says Denis Valode, of Valode & Pistre Architectes, designers of the wider masterplan and the ‘Jardins d’Eau’ residential buildings clad in wood and stone. These buildings, some reserved for rental, are settled between the coast and the new hill modelled to ‘look like it has always been there’, which also cleverly hides Mareterra’s most exclusive villas (some designed by Tadao Ando, Stefano Boeri, Foster + Partners).

Landscape designer Michel Desvigne has layered this land with pine trees and Mediterranean species, a palette consistent across public and private areas of green space that together cover nearly 50 per cent of the masterplan (an extreme rarity, he says, compared to the usual 10-15 per cent). Desvigne has extended his minimalist urban design from the neighbouring Larvotto beach development (also by RPBW), so now there’s a flowing, 4.1km pale limestone coastal pathway, which on its opening morning is busy already with runners, tiny dogs, elderly couples, solo millennials with headphones, parents with strollers and construction workers on their breaks.

Another pathway intersects the micro-forest of pine trees running alongside a stream of water. As the canopy develops, it will become a shaded ‘vault’ that then peels off up the hill into a zig-zagging trail, or onwards to the piazza. Here, one can find the ‘smallest museum’ Renzo Piano has ever designed, a walled courtyard for Calder’s kinetic aluminium and stainless steel sculpture ‘Quartres Lances’ balancing above a square pool of water. When the sun is high and bright, the colours of white, yellow, red and orange emerge on the water’s surface and a breeze generates its motion into ‘total activation’ explains Sandy Rower, president of the Calder Foundation, and grandson of the artist.

Originally designed as a site-specific work for the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, the sculpture was purchased by Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco in 1966. It had been installed close by, yet removed when the Grimaldi Forum, inaugurated in 2000, was built. The Principality and Nouveau Musée National de Monaco (NMNM) have been searching for a worthy new site ever since, in collaboration with the Calder Foundation. When the Mareterra project began to materialise, Rower called up Piano, who had designed a landmark Calder show in Turin in 1983, and amicably designed a dedicated courtyard (with an integrated rope system to tie it down during windy weather and a bench designed by Prince Albert II).

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The Calder Foundation and NMNM are now hatching ideas for a future exhibition, and Björn Dahlström, director of NMNM, says that the Calder’s return to public space was a catalyst for a Monaco-wide sculpture trail launched last year to guide visitors through the extensive collection of outdoor public art, including works by Vasarely, Claude and Francois-Xavier Lalanne, Fernand Leger, Anish Kapoor, Jean Amado and a recently restored series of Roger Capron ceramic tiles.

Another piece of public art at Mareterra is Vietnamese artist Tia-Thuy Nguyen’s immersive and meditative room clad in natural formations and bubbles of pink stone beneath an oculus titled ‘Drops of the Sun’, found behind a small doorway along the promenade. Another door opens to the Blue Grotto, an enigmatic concrete cave that reveals the belly of Mareterra, the five-storey-tall caissons that this whole neighbourhood rests upon. It’s pure sculpture, framing the power of manmade materials and engineering to defy and control nature.

It’s a reminder that despite the transparency and lightness of Piano’s architecture and the natural modelling of the hills, this artificial land is not really floating yet very firmly grounded into the seabed on a foundation carved with the initials of Prince Albert II. Underwater, experimental structures cling to the concrete, with the hope that eventually sea life, the endemic posidonia seagrass, urchins and fish here might learn to thrive alongside modernity, just like we have done in our concrete and steel apartment blocks.

At the launch of Mareterra, Guy Thomas Levy-Soussan, chief administrator of the project, talked passionately about its legacy of underwater research and design stretching back to 2016 in collaboration with marine biologists, open about both successes and failures along the way. Celine Caron-Dagioni, Monaco’s Minister of Equipment, Environment and Urban Planning, hopes that the resources and quality of design that have been invested into the land reclamation project will serve as a prototype for future coastal cities battling rising sea levels.

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

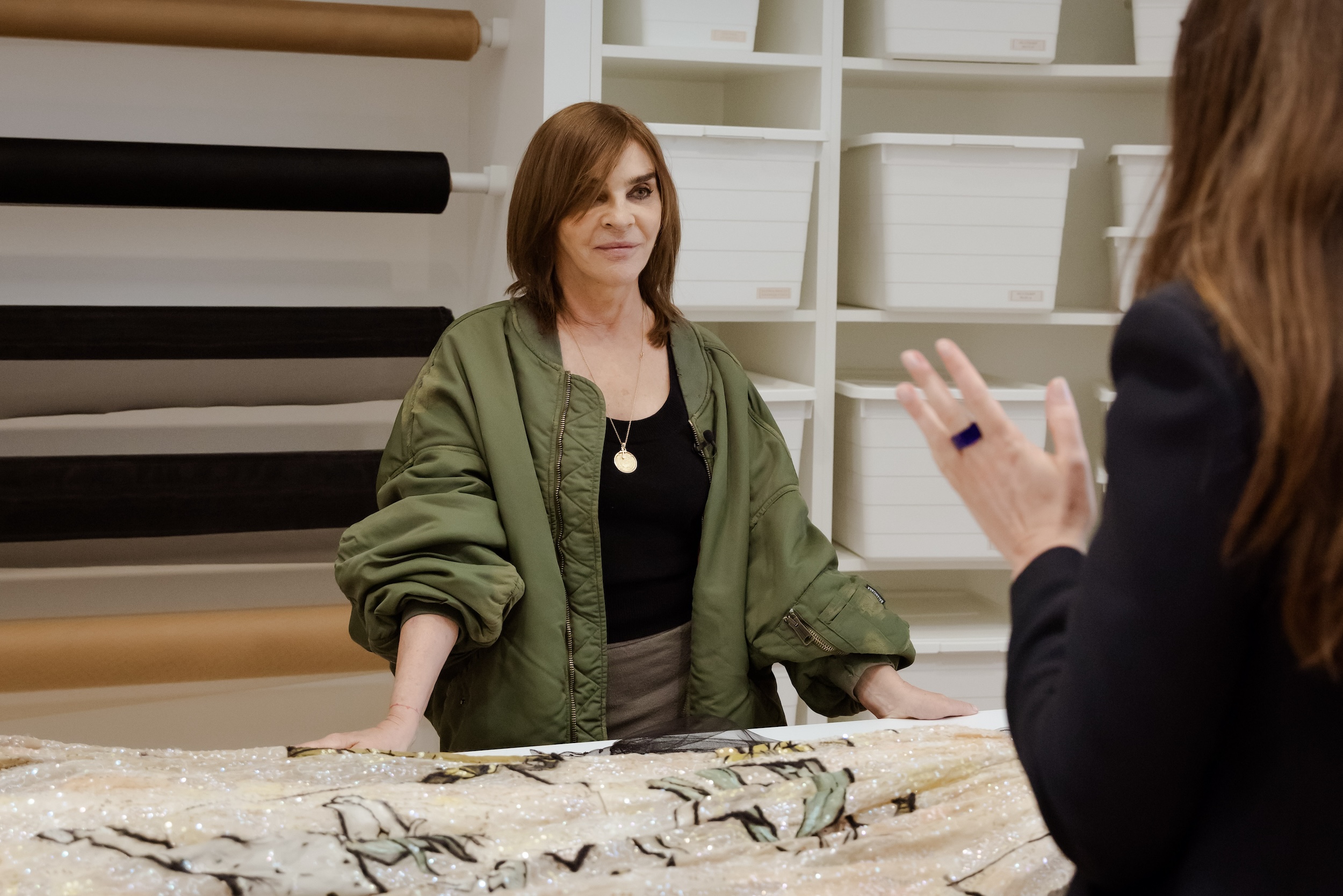

Carine Roitfeld on the magic of Dior

Carine Roitfeld on the magic of DiorThe legendary fashion editor has teamed up with photographer Brigitte Niedermair on a special look into the famed French house's archives as part of the UBS House of Craft x Dior in New York

-

Kvadrat’s new ‘holy grail’ product by Peter Saville is inspired by spray-painted sheep

Kvadrat’s new ‘holy grail’ product by Peter Saville is inspired by spray-painted sheepThe new ‘Technicolour’ textile range celebrates Britain's craftsmanship, colourful sheep, and drizzly weather – and its designer would love it on a sofa

-

MillerKnoll's new archive is a design lover's paradise

MillerKnoll's new archive is a design lover's paradiseThe furniture design powerhouse is opening its vaults to scholars and enthusiasts like. Take a peek inside

-

Mareterra: a new neighbourhood rises in Monaco

Mareterra: a new neighbourhood rises in MonacoMareterra, a Monaco project boasting contributions by Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Stefano Boeri and Tadao Ando, is set to become a new neighbourhood of more than 130 super-prime residences

-

Designer Holly Waterfield creates luxurious pied-à-terre in Renzo Piano Manhattan high-rise

Designer Holly Waterfield creates luxurious pied-à-terre in Renzo Piano Manhattan high-riseA private residence by Holly Waterfield Interior Design in Renzo Piano's skyscraper 565 Broome Soho blends a sense of calm and cosiness with stunning city views

-

CERN Science Gateway: behind the scenes at Renzo Piano’s campus in Geneva

CERN Science Gateway: behind the scenes at Renzo Piano’s campus in GenevaCERN Science Gateway by Renzo Piano Building Workshop announces opening date in Switzerland, heralding a new era for groundbreaking innovation

-

Renzo Piano’s GES-2 V-A-C House of Culture opens in Moscow

Renzo Piano’s GES-2 V-A-C House of Culture opens in MoscowThe V-A-C Foundation celebrates its new design by Renzo Piano – the GES-2 House of Culture in Moscow, set in a former power station

-

Fiat’s iconic modernist factory hosts new urban oasis

Fiat’s iconic modernist factory hosts new urban oasisFiat’s former Lingotto factory and test track are transformed into Europe’s largest hanging garden – a new urban oasis for Turin

-

The buildings adding a new dimension to Miami’s skyline

The buildings adding a new dimension to Miami’s skylineAs the Florida city’s architecture boom continues apace, here’s what’s next

-

Renzo Piano’s GES-2 is a site of wonder

Renzo Piano’s GES-2 is a site of wonderThe GES-2's building site in Moscow is so glorious the half-constructed structure has already got the design world talking

-

Newly completed 565 Broome by Renzo Piano is SoHo’s tallest residential building

Newly completed 565 Broome by Renzo Piano is SoHo’s tallest residential building565 Broome, Renzo Piano Building Workshop's latest residential tower in New York may be SoHo's tallest, but it remains refined and understated thanks to the Italian architect's masterful design