Essential Homes Research Project launches first shelter for displaced communities

The Norman Foster Foundation and Swiss building materials giant Holcim launch the Essential Homes Research Project’s first design – a concrete cabin shelter. Nick Compton met with Norman Foster to find out more

If your world is turned upside down and you’re unhoused by a natural or man-made catastrophe, you will probably end up in a tent. If you’re lucky. The Norman Foster Foundation, working with Swiss building materials giant Holcim, has launched the Essential Homes Research Project and come up with a more substantial, if admittedly more costly, alternative: a quick-build, design-led concrete cabin that promises displaced populations a more dignified, safe, solid and longer-lasting shelter.

The Essential Homes Research Project’s shelter proposal

The design was taken from initial drawings to full-scale prototype in just nine months and unveiled at the launch of the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale.

The cabin is constructed around a take-away frame in two layers of canvas, one corrugated, impregnated with low-carbon concrete. The outer layer is sprayed with water and starts to set within hours, is solid within a day, and the structure can be ready for safe, warm habitation in three to four days.

The corrugated layer adds stability and creates space for foam insulation for colder climate housing. Another insulation layer is added underneath the concrete shell, while bedrooms, kitchens, showers, toilets and dining tables are housed in easily inserted flat-pack, ply-wood pods.

Measuring 6m across and offering 18 sq m of living space, each cabin could house a family of four, the project partners suggest. The modular, reconfigurable design means it could serve a range of other purposes, from office to store to school room.

Foundations are built using recycled demolition materials, while the cabins can be connected by low-carbon permeable pathways packed with light-absorbing, glow-in-the dark aggregates, reducing energy use and light pollution. The Foster/Holcim team argue that the design has an embedded carbon debt 70 per cent lower than a traditional brick or concrete building of the same size.

The component parts of the cabin arrived in Venice in a single truck and the partners suggest they can make transport even more efficient in the future. No cranes are required in the construction, which can be completed by non-specialist teams, including future tenants. ‘If you are involved in the construction process, you have a sense of pride and ownership,’ Foster argues. The cabins have also been designed for easy disassembly and then reuse or recycling.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The project was born of a student/architect workshop, sponsored by Holcim, and run by the Norman Foster Foundation in 2022 at its headquarters in Madrid. The challenge it addressed is huge. There are currently 103 million displaced people around the world, according to the UN. Climate change threatens to massively increase that number, and on average, displaced people spend 20 years in ‘temporary’ shelter.

Intent on reimagining almost instant, almost 'anywhere' housing, the students, advisors from Holcim and Foster himself, took the Ikea Foundation’s ‘Better Shelter’, a tent fitted with polypropylene side-panels and with a three-year lifespan, as a starting point.

Norman Foster working on the project

Foster acknowledges that the Ikea shelter is a vast improvement on the existing alternatives, but it still does the bare minimum. ‘In the workshops, we looked at the best tents on the market, and we just thought, “Oh my God, there are no windows, you can't look out, there's no life. There's no acoustic privacy. There's no joy.”’

Foster says the students set the project’s direction of travel: ‘They were asking, how can this be more like a home? Can it build something more like a community? Can the buildings work together to create public spaces? Could it be less institutional, less like a barracks? Could it be more human?’

The project is presented in a display at Palazzo Mora, Venice

With a current cost of €20,000 per cabin, the Foster/Holcim design isn’t going to be the most affordable option for instant housing. Throwing in some comparative costing maths, when it was launched in 2017, the Better Shelter super-tent cost just $1,250, but the Essential Homes team are arguing their cabin will last at least 20 years. And Edelio Bermejo, Holcim’s head of R&D, says they are already looking at ways to reduce costs.

As the partners argue, though, the cabin design deliberately blurs the boundaries between the temporary and the permanent, and quick-fix shelter and affordable housing, hence the catch-all 'Essential Housing' tag. As much as they spent time studying 'instant accommodation', from yurts to Nissen huts (and the final design has more than a touch of Nissen hut about it), the team behind the design were, says Foster, 'challenging traditional ways of creating a permanent building'.

Exhibition view at Palazzo Mora

For Zurich-based Holcim, the project is a chance to showcase its development of more sustainable concretes and persuade sceptics of its future as a responsible material. It has already established a reputation for delivering innovative construction and infrastructure solutions, building the world’s first 3D-printed school in Malawi and the world’s largest 3D-printed affordable housing project in Kenya.

Holcim and Foster admit that the use of concrete is now a hard sell to many young architects, but insist that lower-carbon concrete is the most viable building material for large-scale projects. And that a priority in the project was using commercially available materials. 'There is a responsibility to separate myths and emotion from the realities of hard data,' says Foster.

Exhibition view at Palazzo Mora

Foster and the rest of the team are clear that the version of the cabin shown in Venice is just a speculative work-in-progress, with design wrinkles still to be ironed out. ‘This is an R&D project and the next step is to test in three different locations,’ says Bermejo. ‘But we have a design, we have the materials, we just need someone to say, “I want this to build a village, a community.”’

The Essential Homes team insist that possibilities are multiple and that the cabin is suitable for everything from temporary housing and long-term affordable housing to an office/studio outbuilding or a holiday cabin. ‘We never imagined that we could push the boundaries and end up with so many people seeing the prototype and saying, “I'd love one of those,”’ says Foster.

-

Volvo’s quest for safety has resulted in this new, ultra-legible in-car typeface, Volvo Centum

Volvo’s quest for safety has resulted in this new, ultra-legible in-car typeface, Volvo CentumDalton Maag designs a new sans serif typeface for the Swedish carmaker, Volvo Centum, building on the brand’s strong safety ethos

-

We asked six creative leaders to tell us their design predictions for the year ahead

We asked six creative leaders to tell us their design predictions for the year aheadWhat will be the trends shaping the design world in 2026? Six creative leaders share their creative predictions for next year, alongside some wise advice: be present, connect, embrace AI

-

10 watch and jewellery moments that dazzled us in 2025

10 watch and jewellery moments that dazzled us in 2025From unexpected watch collaborations to eclectic materials and offbeat designs, here are the watch and jewellery moments we enjoyed this year

-

Zayed National Museum opens as a falcon-winged beacon in Abu Dhabi

Zayed National Museum opens as a falcon-winged beacon in Abu DhabiFoster + Partners’ Zayed National Museum opens on the UAE’s 54th anniversary, paying tribute to the country's founder and its past, present and evolving future

-

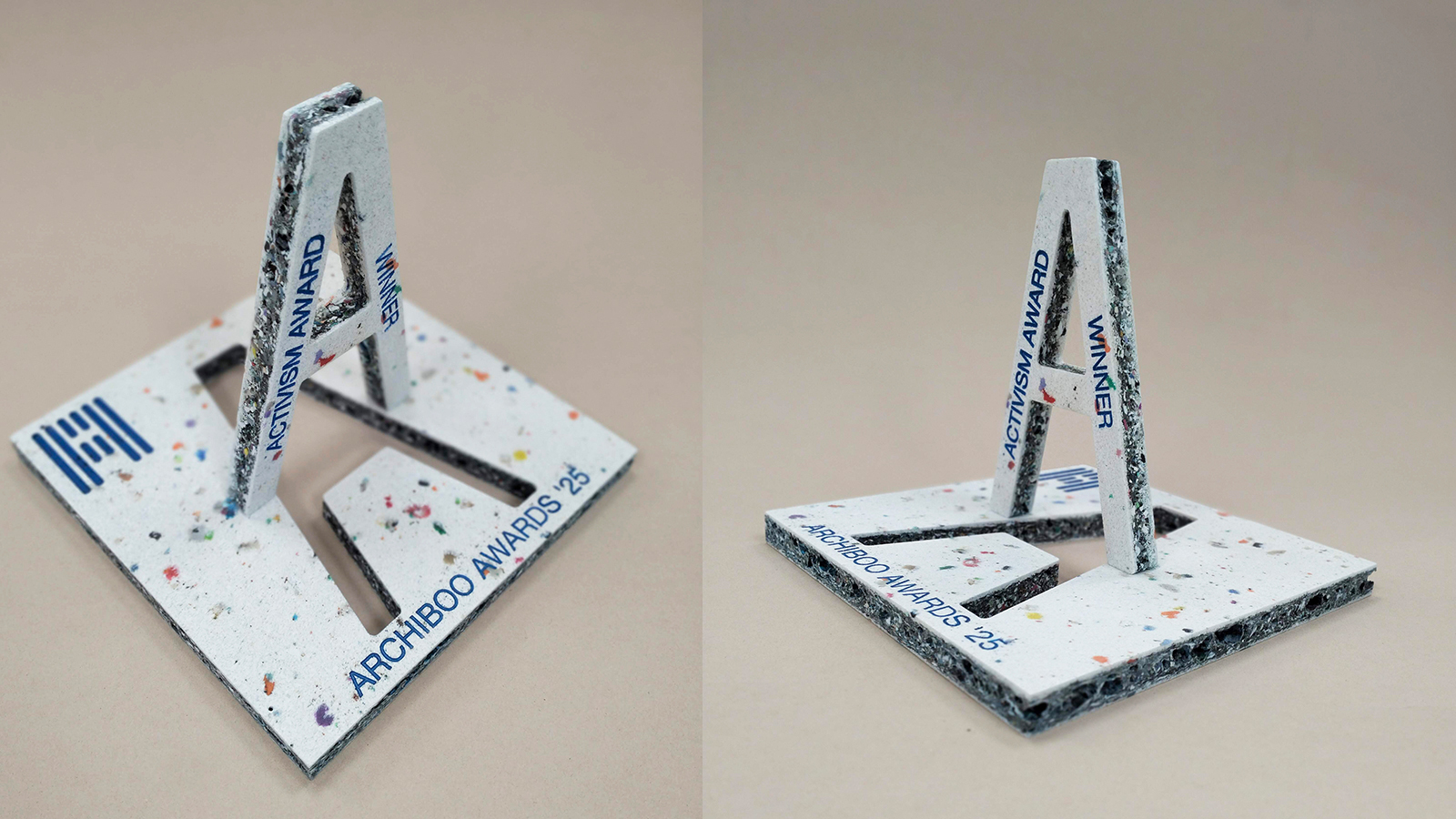

Archiboo Awards 2025 revealed, including prizes for architecture activism and use of AI

Archiboo Awards 2025 revealed, including prizes for architecture activism and use of AIArchiboo Awards 2025 are announced, highlighting Narrative Practice as winners of the Activism in architecture category this year, among several other accolades

-

‘It’s really the workplace of the future’: inside JPMorganChase’s new Foster + Partners-designed HQ

‘It’s really the workplace of the future’: inside JPMorganChase’s new Foster + Partners-designed HQThe bronze-clad skyscraper at 270 Park Avenue is filled with imaginative engineering and amenities alike. Here’s a look inside

-

Will this be the world’s largest airport? Construction begins on King Salman International Airport, open by 2030

Will this be the world’s largest airport? Construction begins on King Salman International Airport, open by 2030Foster + Partners starts construction on its latest project, the expansion of an airport in Saudi Arabia, which could handle up to 100 million travellers a year

-

Foster + Partners to design the national memorial to Queen Elizabeth II

Foster + Partners to design the national memorial to Queen Elizabeth IIFor the Queen Elizabeth II memorial, Foster + Partners designs proposal includes a new bridge, gates, gardens and figurative sculptures in St James’ Park

-

Porsche and the Norman Foster Foundation rethink the future of mobility

Porsche and the Norman Foster Foundation rethink the future of mobilityA futuristic Venice transport hub, created with the Norman Foster Foundation for Porsche’s The Art of Dreams programme, is a star of the city’s Architecture Biennale

-

A mesmerising edition of The Dalmore Luminary Series is unveiled in Venice

A mesmerising edition of The Dalmore Luminary Series is unveiled in VeniceThe Dalmore Luminary Series sculpture No.3 by Ben Dobbin of Foster + Partners, co-curated by V&A Dundee, launches in Venice during the 2025 Architecture Biennale

-

Manchester United and Foster + Partners to build a new stadium: ‘Arguably the largest public space in the world’

Manchester United and Foster + Partners to build a new stadium: ‘Arguably the largest public space in the world’The football club will spend £2 billion on the ambitious project, which co-owner Sir Jim Ratcliffe has described as the ‘world's greatest football stadium’