Olafur Eliasson’s first building completes in Denmark

A new sculptural form rises from the industrial docks of Vejle in Denmark. The Fjordenhus is the first ‘total’ piece of architecture from Olafur Eliasson which combines – and blurs the boundaries between – art, architecture and design. Inside the building, site-specific art works and specially designed furniture and lighting are all designed by Studio Olafur Eliasson.

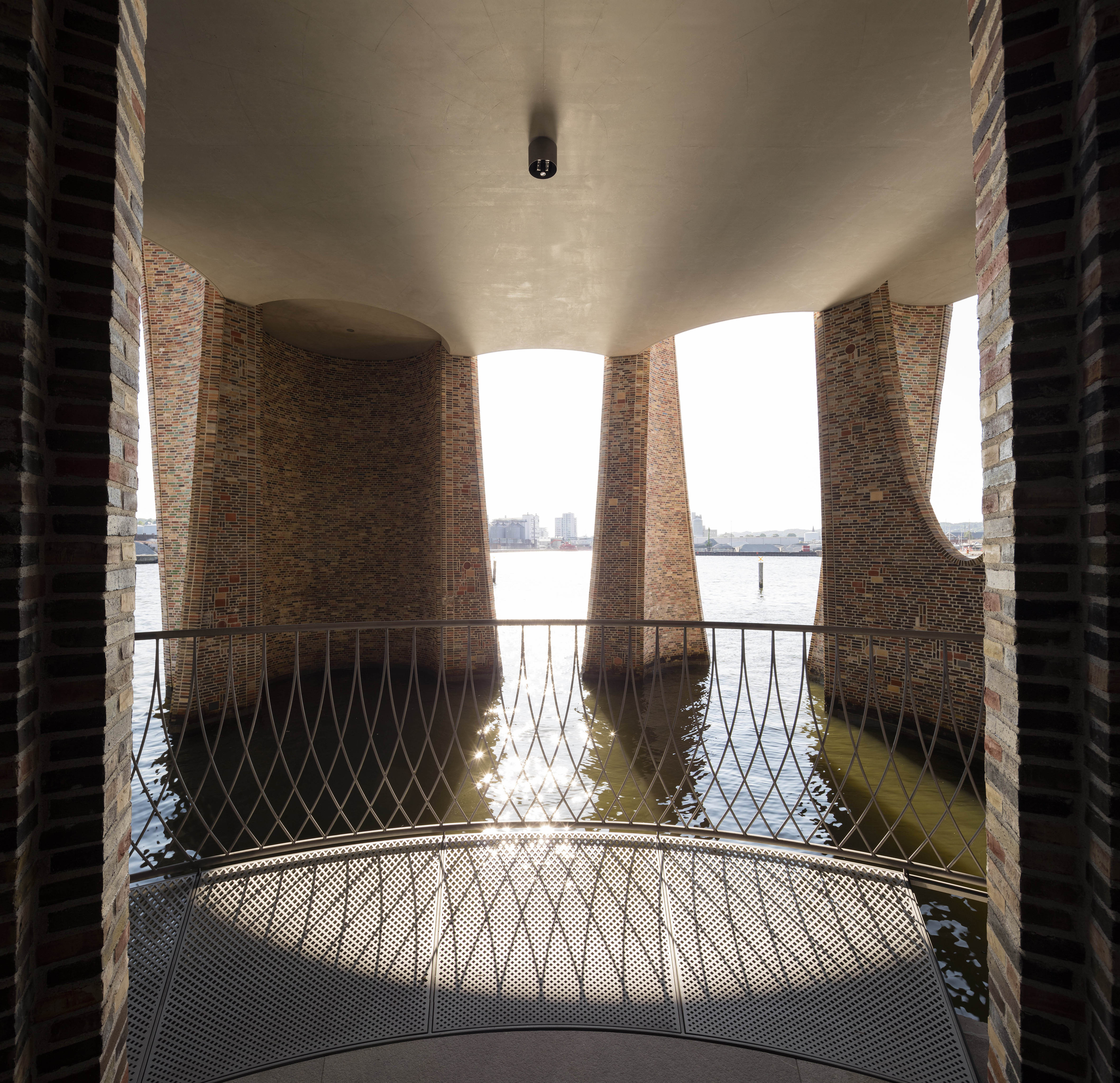

It may look like a post-neo-romantic brick folly – creatively avoiding any association with a standard architectural typology – however, it serves as a headquarters for the Kirk Kapital, a local family-run business working across agricultural, industry and cultural sectors. The ground floor of the building is a publicly accessible space that is an atmospheric void and a viewing platform for the fjord and the surrounding docklands.

Four brick cylinder shapes merge to form the organic main structure. Soaring arches are scooped out to carve entranceways and openings at ground level sheltered balconies for the upper floors. Within the context of the active industrial docklands – where heaps of gravel, stacks of timber pile up in yards, open warehouses reveal steelworkers sparks – it’s impossible not to think of industrial architectural forms. And similar industrial waterfront cultural buildings such as Heatherwick’s MOCAA or Herzog & De Meuron’s brick-based Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg.

Fjordenhus, 2009-2018, by Olafur Eliasson and Studio Olafur Eliasson in Vejle, Denmark.

‘I was happy to reference the industrial history of silos and energy containers, but the circle also has this idea of the meeting space and the parliament – the circle being a shared space,’ says Olafur Eliasson of the design. ‘Each of the three (Kirk) brothers have their own spheres and then there is a sphere in the middle that connects them.’

The Kirk family wanted a building that would celebrate the Vejle fjord, nature, the seasons and the ephemeral quality of the water, and share that with the community. They also wanted the building to play a leading part of the revitalisation of the Vejle docklands. The first job for Olafur Eliasson Studio was to design a masterplan for the dockland area, an artificial piece of land built 200 years ago for industry of the Jutlands. The team decided to take the Fjordenhus off the land and into the water. Building on the water in Denmark is nothing new to a country with 7000 km of coastline, explained Eliasson, yet the choice was also part of the celebration of the qualities of the water.

This move also opened up space for a broad cobbled public square and uninterrupted views from Vejle’s high street straight out to the fjord and the graceful 1712-metre-long Vejle Fjord Bridge. The public square is a place to be ‘aimless’ and ‘foolish’ in says Eliasson: ‘A lot of public space has become obsessed with control and defining normality as a certain type of behaviour – a little bit like museums. The lack of diversity in behaviour you see in museums is unbelievable, everybody is becoming robots.’

Eliasson commissioned a long, tapering jetty designed by landscape architect Gunter Vogt that extends from the square towards the fjord. Vogt is a long-term friend and mentor to Eliasson, who describes him as a ‘great humanist and a great protestant: I love his very minimalist and down to earth approach, he is a great source of inspiration.’

Fjordhvirvel, 2018, by Olafur Eliasson installed at the Fjordenhus, Vejle, Denmark.

This very Danish approach to a humanistic architecture is clear across the ground floor level of the Fjordenhus, a space that Eliasson underlines as a ‘public accessible’ space instead of a ‘public’ space: ‘The idea was for contemplative space, or a space where we can celebrate the atmospheric conditions – the quality of the air and the wind.’ Eliasson admits that this is something he needs to ‘learn’ to speak about, because the qualities of this space are actually beyond language.

‘This is something I’m working on,’ he says. ‘My work has been about that for a while and I love it, I love nature. But loving nature is not enough. We need to harvest, harness, protect, and organise it. We need to acknowledge that the so-called atmospheric spaces in our lives have also become political and economical. These so-called “non-quantifiables” will define our lives in the future. I’m not a climate scientist, but as an artist, what I’m trying to say is that wind is not just poetry.’

‘The wind is annoying, but it’s part of the eco-system that drives the clouds and the sun, the light and everything around. We should learn that the wind is not only going to be one of the significant energy drivers of the future, but it’s also amazing because it allows us to feel the invisible. It is the way to detect an empty space, and its something we need to work a lot harder on understanding, because that thing is also called the climate.’

The ground floor opens up a honeycomb of brick arches and voids. The geometry of the architecture balances an inner circle with an outer elipse to create a feeling of ‘tilting’ and ‘leaning’ offering a ‘constant negotiation’ between space and visitor. It provides multiple options and eliminates the neo-classical agenda of Panopticism says Eliasson, who explains that the experience goes beyond phenomenology.

The ground floor of the Fjordenhus in Vejle, Denmark.

‘We need these non-prescriptive spaces. It’s not actually empty, it’s full of opportunity. We need to dare to claim it and say this is nobody’s space. If you go to Brazil, every street corner has a multiplicity of activities; the Italian piazzas used to be these meeting points for the community, kids going to school – I like this idea of a street parliament. Denmark being so unbelievably socially robust, there are no street parliaments – it’s a longer discussion, and one I don’t have the answer to.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Visible from the bridge, the intriguing form of the Fjordenhus will no doubt draw architecturally curious Eliasson fans down into Vejle for a stroll. Thus the building also plays the role of a cultural lighthouse.

When you reach the flat, open cobbled square, and move closer, you will see the detailing of the brick-work, the buildings’ most beautiful feature. Eliasson describes the brickwork as ‘expressionistic’ where ‘hidden murals’ swell and disappear into the walls. He wanted the brickwork to express how it was made by human hands, and he hopes that eventually a seed with find its way onto a ledge to soften the form with some nature. In the studio, the team formed the colour scheme and patterns of the bricks, working with Peterson brick contractors for the work. Glazed green bricks are scattered close to the base of the building while higher up glossy blue-glazed bricks connect the building to the sky.

While the Fjordenhus is a first for Eliasson and his studio, architecture isn’t a new realm. Eliasson is very familiar with space and building. His installations often move beyond walls such as at his rainbow panoramic corridor at the Aarhus Kunst Museum (2011), the reflective, cellular facades for Iceland’s Harpa concert hall (2013) and his reflective colonnade at the Louis Vuitton Foundation (2014).

The Fjordenhus was an opportunity for Eliasson to bring together the knowledge and experience of his studio – the processes of making, building exhibitions, researching materials and collaborating with a trusted network of technicians and engineers, yet also designing a narrative, making an atmosphere, working with light.

Architect Sebastian Behmann, worked closely with Eliasson on the project and has been working with him since 2001, now holding the position of head of the department of design. Behmann jokes that this is Studio Olafur Eliasson’s first, and last, total building project, as the pair have co-founded Studio Other Spaces, to take on further architectural commissions.

As an artist, Eliasson has the ability to approach architecture a unique way – perhaps favouring form over function, daring to building a non-functional space, happily ignoring typology. Yet, while an architect may prickle at the very sound of this approach, Eliasson makes some eloquent and necessary statements about the environment, public space and beauty with his Fjordenhus and he certainly knows how to harness an atmosphere.

For more information, visit the Studio Olafur Eliasson website and the SOS (Studio Other Spaces) website

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

Step inside Rains’ headquarters, a streamlined hub for Danish creativity

Step inside Rains’ headquarters, a streamlined hub for Danish creativityDanish lifestyle brand Rains’ new HQ is a vast brutalist construction with a clear-cut approach

By Natasha Levy

-

This restored Danish country home is a celebration of woodworking – and you can book a stay

This restored Danish country home is a celebration of woodworking – and you can book a stayDinesen Country Home has been restored to celebrate its dominant material - timber - and the craft of woodworking; now, you can stay there too

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Greenland through the eyes of Arctic architects Biosis: 'a breathtaking and challenging environment'

Greenland through the eyes of Arctic architects Biosis: 'a breathtaking and challenging environment'Danish architecture studio Biosis has long worked in Greenland, challenged by its extreme climate and attracted by its Arctic land, people and opportunity; here, founders Morten Vedelsbøl and Mikkel Thams Olsen discuss their experience in the northern territory

By Ellie Stathaki

-

The Living Places experiment: how can architecture foster future wellbeing?

The Living Places experiment: how can architecture foster future wellbeing?Research initiative Living Places Copenhagen tests ideas around internal comfort and sustainable architecture standards to push the envelope on how contemporary homes and cities can be designed with wellness at their heart

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Denmark’s BIG has shaped itself the ultimate studio on the quayside in Copenhagen

Denmark’s BIG has shaped itself the ultimate studio on the quayside in CopenhagenBjarke Ingels’ studio BIG has practised what it preaches with a visually sophisticated, low-energy office with playful architectural touches

By Jonathan Bell

-

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practices

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practicesIn the Wallpaper* Architects Directory 2024, our latest guide to exciting, emerging practices from around the world, 20 young studios show off their projects and passion

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Meet Mast, the emerging masters of floating architecture

Meet Mast, the emerging masters of floating architectureDanish practice Mast is featured in the Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024

By Jens H Jensen

-

A redesigned Aarhus showroom reinterprets Danish history through modern context

A redesigned Aarhus showroom reinterprets Danish history through modern contextDanish architecture studio Djernes & Bell transforms the Aarhus showroom for Dinesen and Garde Hvalsøe by blending old and new

By Tianna Williams