Helsinki opens a light-filled library as a national monument to education, sharing and books

‘I think it’s quite unique to build a library in a city today,’ says Jan Vapaavuori, mayor of Helsinki. The city has just opened Oodi, a new central library designed by Finnish architecture firm ALA located opposite the Helsinki’s Parliament House on Finland’s 101th anniversary of independence. What makes Oodi even more unique, is that it’s also an ‘open user platform’ for sewing, gaming, 3D printing, playing music, soldering, cooking and socialising.

This doesn’t seem to be as radical to the Fins, as it does to those from other countries around the world. Libraries have long operated in Finnish society as community hubs that are flexible and functional in many ways – and that’s probably one of the reasons why Finland is known for its credentials in literacy and education. ‘From the very beginning we realised the only real natural resource we have is human capital,’ says Vapaavuori, ‘Oodi symbolises our way of putting people first.’

The architectural competition for the library launched in 2012 with a record number of 546 entries – in Finland’s typically fair and democratic way, open calls for architectural competitions are also anonymous. It was an opportunity to design a national monument in the very centre of the city neighbouring Parliament House, Alvar Aalto’s Finlandia Hall, the Kiasma designed by Steven Holl and the Helsinki Music Centre.

The exterior of the Oodi central library in Helsinki.

ALA, with their first major cultural building, a theatre and concert hall in Kristiansand, Norway, just under their belt, entered. Antti Nousjoki, partner at ALA, who had previously worked for five years on OMA’s Seattle Public Library, brought his international experience and local knowledge of the Finnish library system to the project – ‘Growing up in a small town, the library is like an extension of your home,’ he says.

The design process started with an analysis of function, which was a lot more varied than you might expect. As well as a library, the architecture has to express the public role of a national monument, and provide space for the activities destined for it from music studios to gaming rooms, a kitchen and workshops – all accessible with a library card.

The architects landed on a plan for three levels; an open ground floor; a floating box; and a space on top of the box. This followed the need for a welcoming, social space worthy of its location, a black box maker space with a matrix of rooms for multimedia activities and also, the traditional library with bookcases.

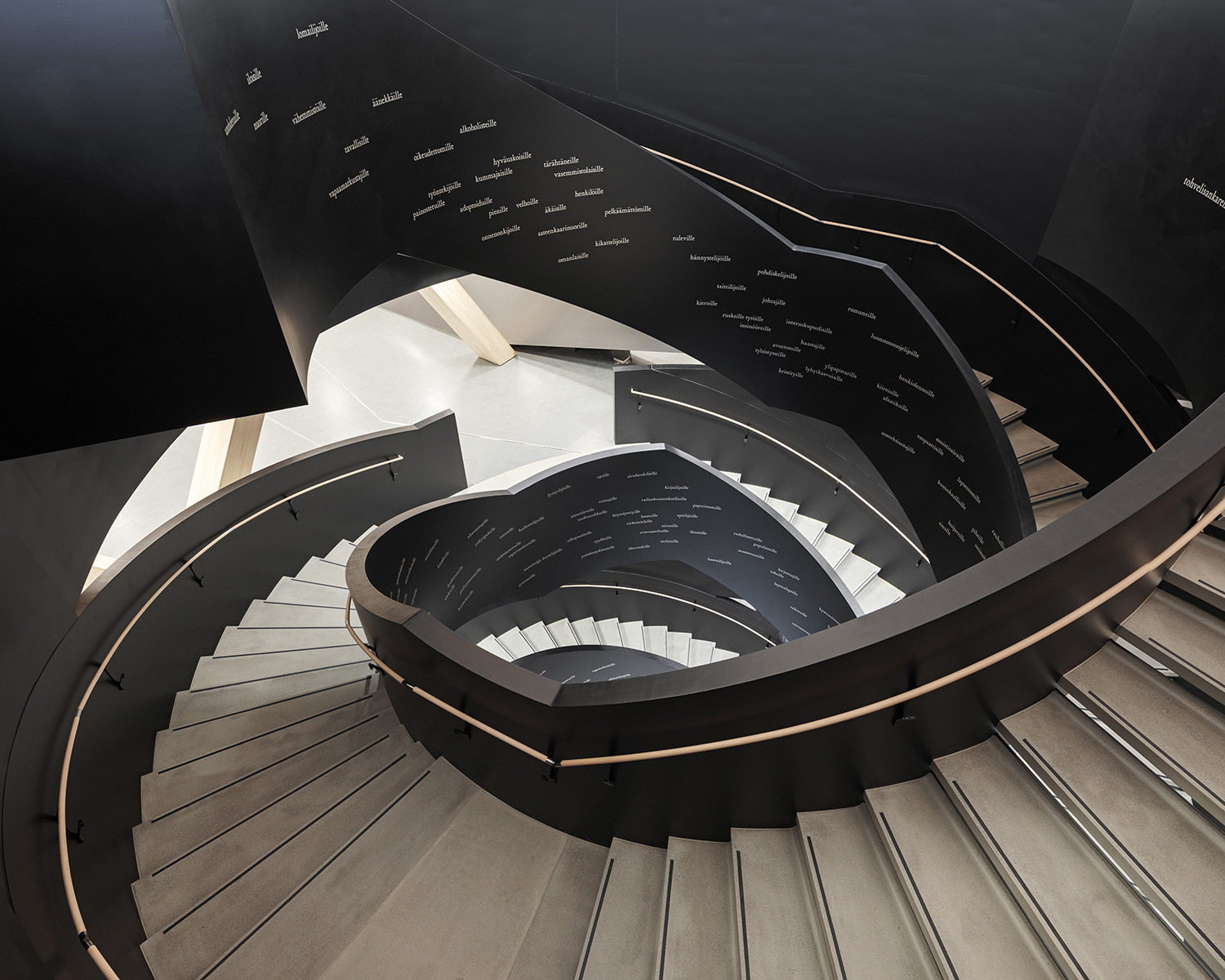

The double spiral staircase

The team then worked with structural engineers to achieve a solution that would leave as much open column free space where it was needed. A 100m arched bridge of steel is the basis for the design. The two open-plan levels sit above and beneath the bridge, while the makers space occupies the bridge itself, and a double spiral staircase connects all three together. ‘The overall shape is not primarily structural, it’s functional and sociological. Its a manipulated diagram of these three conditions,’ says Nousjoki.

Filled with light and rows of Libreria CF bookcases in white-painted aluminium designed by Dante Bonuccelli and manufactured by UniFor, the upper library space is the crowning jewel of the building. Like an undulating halo, the vast roof’s soft curves feature scoops of circular skylights. Nousjoki describes how in certain lights the corners of the ceiling blend with the fritted glazing that wraps around the level to create a continuous cloud-like effect. As well as a source of daylight, the skylights add warm artificial light, important during the winter months, when the library will be a beacon for the city in the dark mornings and afternoons.

RELATED STORY

‘We didn’t want to make a flat box because that would have generated a large space of consistent conditions across the 4000-and-something square metres of space. By making the roof wavy, every square metre is slightly different – the acoustics, the height, the views vary, so people can take time to find a particular area to suit their mood.’

The ‘sunlit, cathedral-like library’ brings a nostalgic sense of pride and praise for the age of the book – ‘this message will become more pronounced as technology advances, or the space will become like the social open programme of the ground floor or specific niche space of the middle floor,’ says Nousjoki.

The biggest worry of Katri Vänttinen, director of the library, is that libraries will become like museums in the future. She sees vast changes in how people use the library every year – lending of the music collection is decreasing by 15 per cent every year, thanks to music giants Spotify and Youtube. Yet, Finnish libraries continue to receive visitors, responding with new resources such as the maker’s space on the first floor. It’s a space filled with tools, aimed at teens, young people and professionals, where you could spend days investigating the recording studios, kitchen, workshops and gaming studios: ‘You can do anything here, it just takes imagination,’ says Tommi Laitio, executive director of culture and leisure at City of Helsinki.

The interior of the upper library floor.

Architecturally incredible libraries are part of the fabric of Helsinki, from the impressive National Library designed by Carl Ludvig Engels in 1844 with its neoclassical rotunda extension designed by Gustaf Nyström, to Alvar Aalto’s university library framed by hanging lamps and campus views, or the uplifting Kaisa library designed by AOA in 2012 with its teardrop shaped central staircase. And far from just beautiful, they are all most importantly filled with people.

The purpose of Oodi in its central location has a strong symbolic value for the city. ‘Sharing is becoming mainstream’ says Vapaavuori, and the library welcomes activities to take place in the urban space instead of in the private home.

As well as the local community, Vapaavuori hopes that the library will tempt international talents to move to the city to work. ‘The issue of a good life is becoming more important all the time. I have conversations with the leading companies in our eco system and they face the issue of how to bring international talents to Helsinki – it’s often not just a question of how good the company, is or how lucrative the job is, it’s how well the city is placed in people’s minds and today’s youth. They value cultural, arts issues, how easy going the city is, how safe it is, how clean it is.’

‘By building a library in 2018, we want to contribute to an overall image of a liberal, transparent, open, city that values culture arts democracy, open society. In today’s world where you compete for investments and talent, soft power is gaining importance – art museums and theatres are built everywhere, but not libraries.’

The Libreria CF bookcase system, designed by Dante Bonuccelli and manufactured by UniFor, consists of aluminum shelving with sheet stell supports and base. A total of 351 double-sided modular bookcase modules, all of them painted white, were fabricated in various versions and customised for the library.

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the ALA website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism‘About Time’, an Australian bathhouse designed by Goss Studio, balances brutalist architecture and the softness of natural patina in a Japanese-inspired wellness hub

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: celebrating architectural projects that restore, rebalance and renew

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: celebrating architectural projects that restore, rebalance and renewAs we welcome 2025, the Wallpaper* Architecture Awards look back, and to the future, on how our attitudes change; and celebrate how nature, wellbeing and sustainability take centre stage

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Alvar Aalto: our ultimate guide to architecture's father of gentle modernism

Alvar Aalto: our ultimate guide to architecture's father of gentle modernismAlvar Aalto defined midcentury – and Finnish – architecture like no other, creating his own, distinctive brand of gentle modernism; honouring him, we compiled the ultimate guide

By Vicky Richardson

-

Design Awards 2025: Alvar Aalto's Finlandia Hall is a modernist gem reborn through sustainability and accessibility

Design Awards 2025: Alvar Aalto's Finlandia Hall is a modernist gem reborn through sustainability and accessibilityHelsinki's Finlandia Hall, an Alvar Aalto landmark design, has been reborn - highlighting sustainability and accessibility in a new chapter for the modernist classic

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Exclusive first look: Katajanokan Laituri sets a new standard for timber architecture

Exclusive first look: Katajanokan Laituri sets a new standard for timber architectureKatajanokan Laituri, a new building in the historic Kauppatori market district of Helsinki, is made from around 7,500 cubic metres of wood, cementing Finland’s position as leader in sustainable architecture, construction and urban development

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practices

Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024: meet the practicesIn the Wallpaper* Architects Directory 2024, our latest guide to exciting, emerging practices from around the world, 20 young studios show off their projects and passion

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Nordic minimalism meets warm personality at Studio Collaboratorio’s new home in Finland

Nordic minimalism meets warm personality at Studio Collaboratorio’s new home in FinlandThe emerging Finnish practice Studio Collaboratorio is welcomed into the Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2024

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Skateboarding in swimming pools: the case of Alvar Aalto’s Villa Mairea

Skateboarding in swimming pools: the case of Alvar Aalto’s Villa MaireaA family of shows at Aalto2 Museum Centre explores skateboarding in swimming pools through the case study of Alvar Aalto’s Villa Mairea in Finland

By Francesca Perry

-

Modernist architecture: inspiration from across the globe

Modernist architecture: inspiration from across the globeModernist architecture has had a tremendous influence on today’s built environment, making these midcentury marvels some of the most closely studied 20th-century buildings; here, we explore the genre by continent

By Ellie Stathaki