Open architecture on building and China’s cultural landscape

Open Architecture’s perfectly considered projects either disappear into the landscape or become new landmarks

Jin Jia Ji - Photography

Huang Wenjing and Li Hu came of age as architects in New York, after they graduated from Beijing’s Tsinghua University in the 1990s. It was there – while Li was at Steven Holl Architects and Huang at Pei Cobb Freed & Partners – that they had the idea of starting their own practice. Having gained more experience and a clearer understanding of architecture, the pair eventually opened their Beijing office, Open Architecture, in 2008, the year of the Beijing Summer Olympics, on one of the capital’s distinctive hutongs; their office is still there today.

The name Open Architecture was inspired by the type of open-source computer hardware or software that allows a simple, free and customizable interchange of components. One of the pair’s earlier projects, Beehive Dorm, a 2009 modular building system made from prefabricated steel-framed hexagonal cells, could be seen as a direct architectural realization of this principle.

Open Architecture’s studio is located on an old Beijing hutong. On the walls are shots of the practice’s 2019 Tank Shanghai and Pingshan Performing Arts Center in Shenzhen

The practice’s breakthrough project was the Beijing No.4 High School Fangshan Campus (widely known as the ‘Garden School’) in 2014. At the time, local authorities were aiming to move away from standard inner city schools – a big block adjacent to a vast, usually empty field – and build schools with more natural outdoor environments. ‘There is a huge demand for better education as the population is getting more affluent, and we wanted to create a new typology for schools,’ says Li. Open’s design placed communal facilities, such as the canteen, auditorium and gymnasium, underground, while covering the site with gardens that reached over the rooftops, giving a view of nature to the students and staff in the classrooms, laboratories and offices.

This unconventional approach to space redefined the various formal and informal educational areas, and led to new thinking about openness, interaction and creativity in a learning environment. With Shanghai’s Qingpu Pinghe International School in 2020, the studio took the theme further by turning the campus into a village with 13 buildings stretching across a landscaped, 50,350 sq m site that included a library and theatre called the Bibliotheater, which is open to the public. It was a site-specific solution to local needs – as all their projects are.

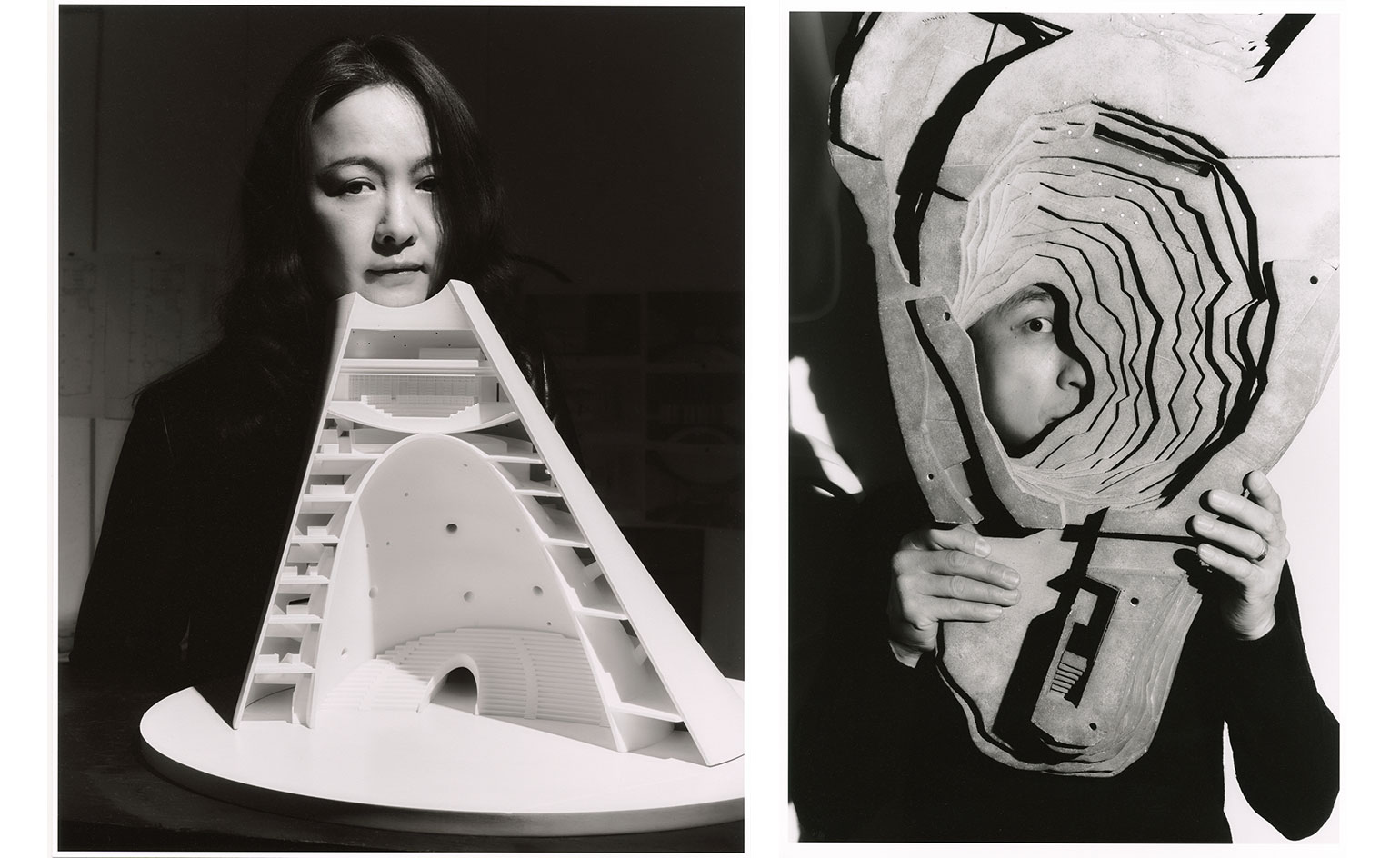

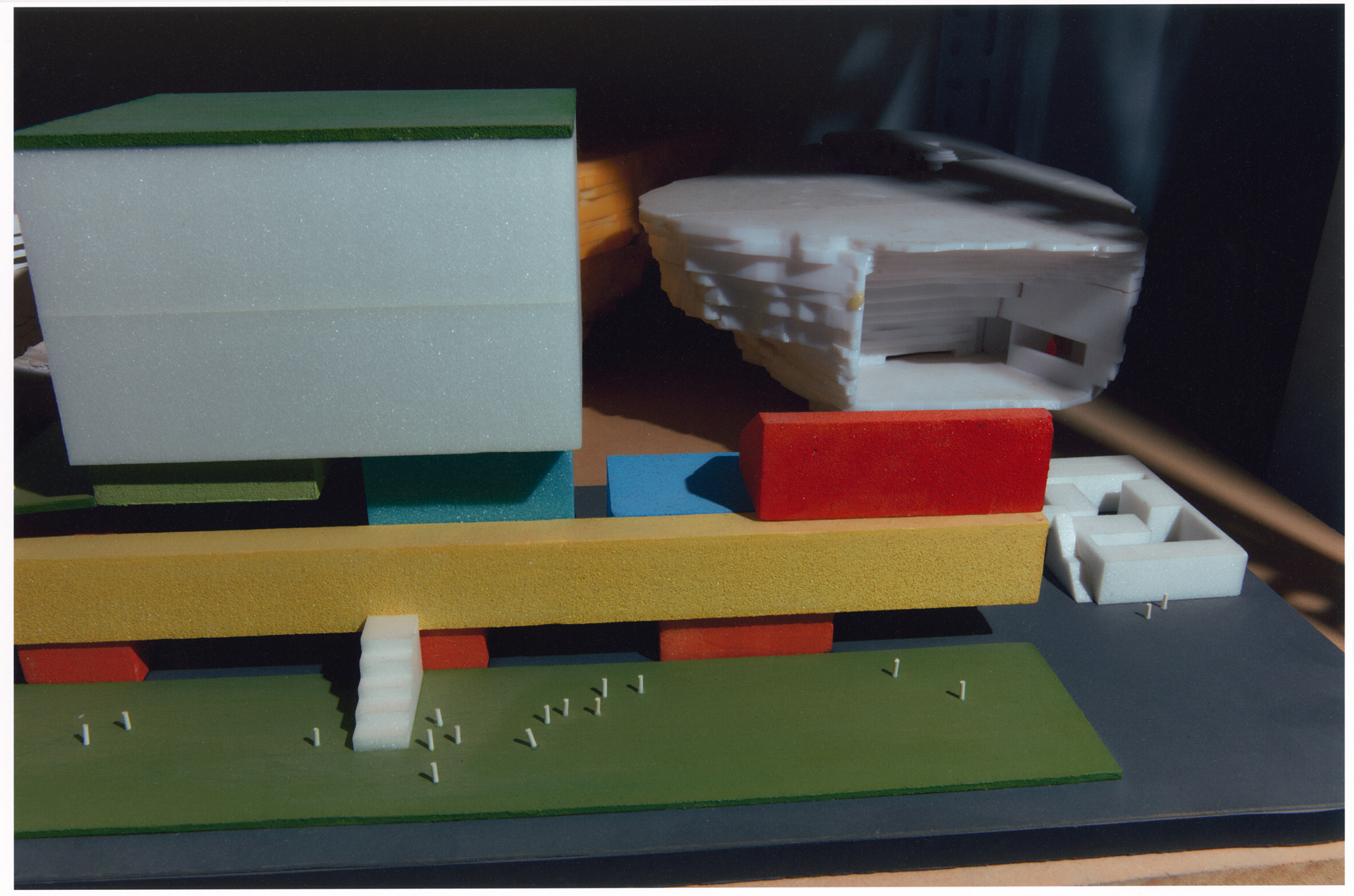

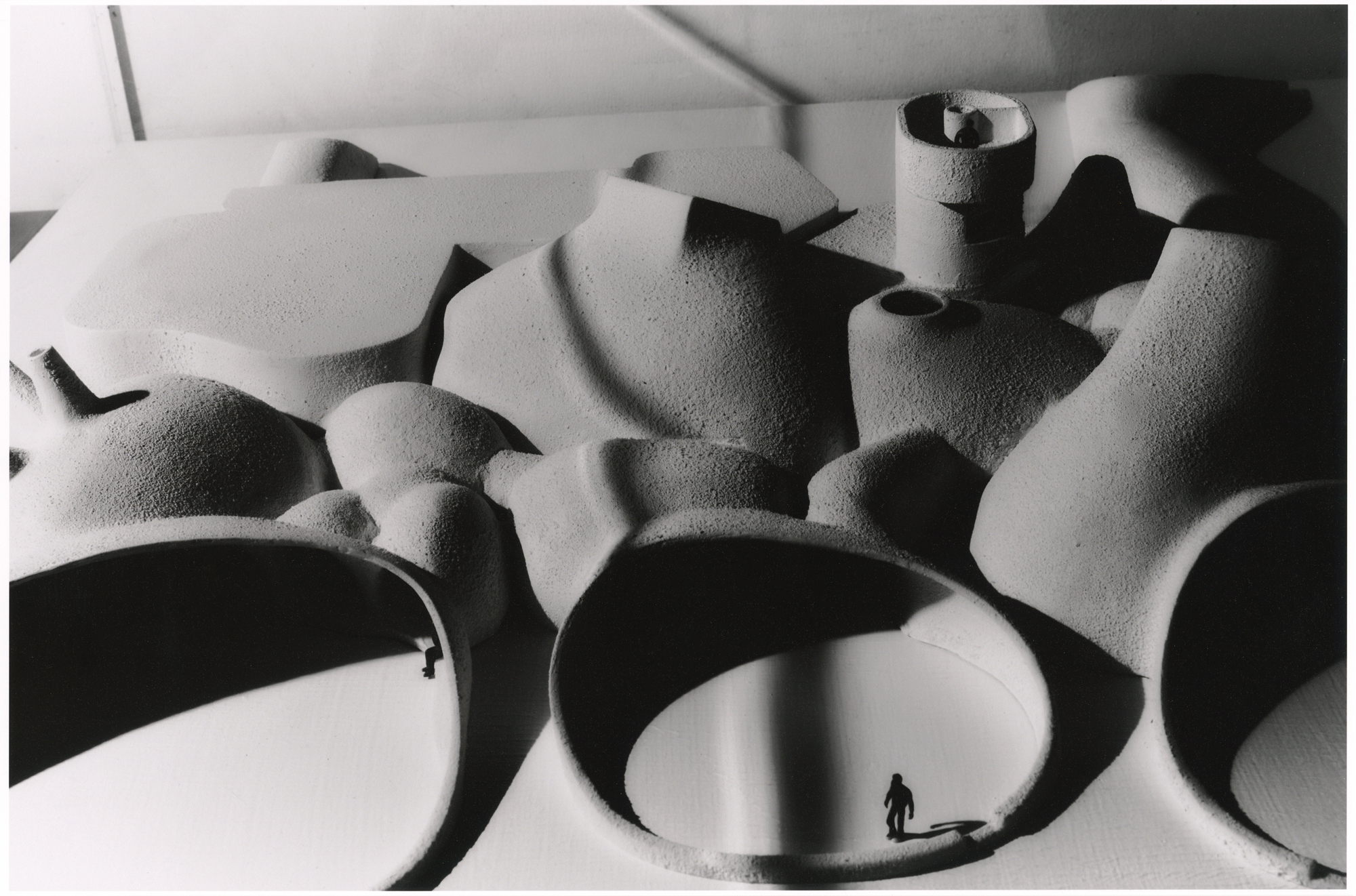

Above, models of recent projects, including, left, a study for an art centre in Beijing, and, right, the 2021 Chapel of Sound. Below, a model of the UCCA Dune Art Museum in Qinhuangdao, a series of interconnected, organically shaped concrete ‘caves’

When Open Architecture launched, China was facing an explosion of urban development that brought plentiful opportunities – even though this came hand in hand with a fair amount of chaos. ‘On our return, we had to readjust ourselves culturally to the way we work. We used to struggle with the lack of definition and clarity in many situations,’ Huang recalls. ‘But then we learnt to first identify the problems in the chaos and then see what the possibilities were.’ A unique challenge for architects in China is that they are often commissioned to create a cultural building without knowing its eventual contents or even its intended use. ‘In tandem with China’s economic boom and rapid urbanisation, the country is at a point when we need more cultural buildings; there is a strong push from the top down, but there are not enough local creatives yet,’ says Li.

For Shenzhen’s 2019 Pingshan Performing Arts Center, the design brief was extremely limited – a grand theatre was needed for a newly developed district. Yet, conversely, the lack of specifics gave the architects the freedom to project their own vision for the building – an institution that connected with the general public and enriched everyday urban life. Huang and Li studied the country’s theatres and assembled a team of experts to put in place a comprehensive scheme for both the building design and its future programming. So successful was their proposal that it was adopted by the site’s operators once they took over.

Above and below, UCCA Dune Art Museum, 2018: Located on a quiet beach on Bohai Bay, Qinhuangdao, this unusual network of subterranean concrete galleries was designed to preserve the dune system. Photography: Open Architecture, Wu Qingshan

As one of the leading players in a new generation of Chinese architects, Open is now defining the nation’s built environment on its own terms, understanding both the existing culture and its future potential. As a research-based practice, it conceives its work along two parallel lines that inform each other: one is studying to produce ideas and critiques, and the other designing buildings that generate revenue for them.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Adaptive reuse is one of Open’s key areas of research, as another recent project displays. Along the banks of Shanghai’s Huangpu River, now the West Bund Culture Corridor, was a dilapidated site with five decommissioned aviation fuel tanks and other forgotten relics of the city’s former airport. Paying tribute to the site’s industrial past, while also seeking to dissolve conventional perceptions of art institutions with formidable walls, they created Tank Shanghai, an art centre-cum-open park, in 2019. The tanks are now linked via a new basement, while two new gallery spaces sit in the surrounding landscape. Lush greenery laces the different elements in the 47,450 sq m site. Called the ‘Super-Surface’, it provides much-needed parkland in a city that is less than 20 per cent green space. The site has since seen a return of urban wildlife.

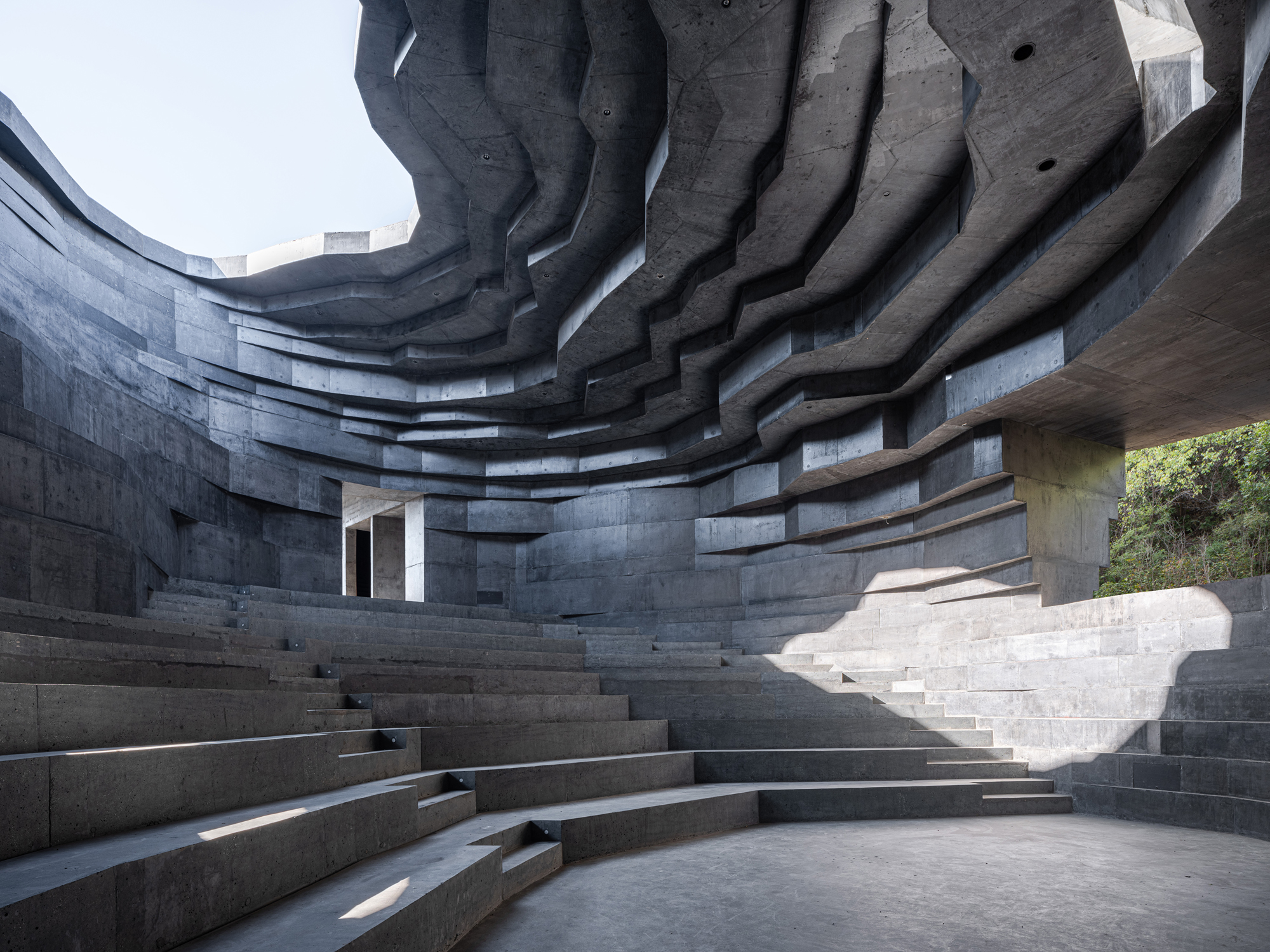

Above and below, Chapel of Sound, 2021: Located near the Great Wall of China, this outdoor concert hall is made entirely of concrete. Judiciously placed openings allow the sounds to flow in and out. Photography: Jonathan Leijonhufvud, Zhu Runzi

‘We had trouble documenting the space because the photographers can’t see where the architecture is,’ adds Huang. ‘But we embedded some hints throughout the landscape – there is an oculus and openings on the tanks that suggest activities; most of the architecture is happening inside.’ A similar gesture can be experienced at the 2018 UCCA Dune Art Museum, located on a quiet beach in Qinhuangdao. Resembling a primeval habitat, it is a series of connected cave-like structures beneath the sand dunes, each housing a different space. Skylights bring nature into the underground structures, which offer shelter for the body and soul.

Their designs have a lot to do with coexisting with nature, says Huang, and one of their latest works is a fitting example. Extruded from remnants of the Great Wall, the 2021 Chapel of Sound is a semi-outdoor concert hall situated in an uninhabited valley in Chengde. It was designed in pursuit of the purest experience of sound. The chapel’s exterior is a rugged mix of concrete and crushed local rock that feels otherworldly and timeless; its layered structure made it simple to build (and thus feasible in its remote location) while echoing the striated rock formations of the nearby mountains. The compact structure houses a semi-outdoor amphitheatre and an alfresco stage, including a rooftop viewing ‘plateau’ looking over the valley and nearby Great Wall. In the words of the architects, its existence is ‘collecting, reflecting and resonating with nature’.

Above and below, Sun Tower, under construction: This 50m-tall tower in Yantai, on the Yellow Sea coast, will feature an outdoor theatre and winding exhibition space, as well as a viewing platform and water features. Images: Open Architecture

Currently under construction in Yantai, Shandong, the Sun Tower is a key upcoming project: a monolith with a similarly unearthly presence. Its conical form is sliced open to create a half-enclosed structure, its floors connecting to a winding exhibition space to be filled with digital contents. At the top of the tower is an expanse that looks over the splendours of the natural world; water features in the plaza beneath pay homage to the 24 solar terms of the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar, and a water channel marks the equinoxes.

The Sun Tower is destined to be a landmark; Li also wants it to ‘evoke the ancient rituals of nature-worship while providing much-needed cultural facilities in the newly urbanized district’. Open Architecture seeks to meet people’s physical, cultural and aesthetic needs, while avoiding the often overwhelming bureaucratic and financial obstacles that still hamper architectural development in China. The practice flourishes because it seamlessly weaves social benefit into its creations. The pair conclude: ‘We hope we can bring out the multifaceted nature of China. What we have come to realize is that people have many more similarities than differences in how they want their lives to be.’

INFORMATION

Open Architecture’s monograph, Reinventing Cultural Architecture, written by Catherine Shaw (£35, Rizzoli), is out now

A version of this article appears in the May 2022 issue of Wallpaper*. Subscribe today!

Yoko Choy is the China editor at Wallpaper* magazine, where she has contributed for over a decade. Her work has also been featured in numerous Chinese and international publications. As a creative and communications consultant, Yoko has worked with renowned institutions such as Art Basel and Beijing Design Week, as well as brands such as Hermès and Assouline. With dual bases in Hong Kong and Amsterdam, Yoko is an active participant in design awards judging panels and conferences, where she shares her mission of promoting cross-cultural exchange and translating insights from both the Eastern and Western worlds into a common creative language. Yoko is currently working on several exciting projects, including a sustainable lifestyle concept and a book on Chinese contemporary design.

- Jin Jia Ji - PhotographyPhotographer

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Bold, geometric minimalism rules at Toteme’s new store by Herzog & de Meuron in China

Bold, geometric minimalism rules at Toteme’s new store by Herzog & de Meuron in ChinaToteme launches a bold, monochromatic new store in Beijing – the brand’s first in China – created by Swiss architecture masters Herzog & de Meuron

By Ellie Stathaki

-

The upcoming Zaha Hadid Architects projects set to transform the horizon

The upcoming Zaha Hadid Architects projects set to transform the horizonA peek at Zaha Hadid Architects’ future projects, which will comprise some of the most innovative and intriguing structures in the world

By Anna Solomon

-

Liu Jiakun wins 2025 Pritzker Architecture Prize: explore the Chinese architect's work

Liu Jiakun wins 2025 Pritzker Architecture Prize: explore the Chinese architect's workLiu Jiakun, 2025 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate, is celebrated for his 'deep coherence', quality and transcendent architecture

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Zaha Hadid Architects reveals plans for a futuristic project in Shaoxing, China

Zaha Hadid Architects reveals plans for a futuristic project in Shaoxing, ChinaThe cultural and arts centre looks breathtakingly modern, but takes cues from the ancient history of Shaoxing

By Anna Solomon

-

The Hengqin Culture and Art Complex is China’s newest cultural megastructure

The Hengqin Culture and Art Complex is China’s newest cultural megastructureAtelier Apeiron’s Hengqin Culture and Art Complex strides across its waterside site on vast arches, bringing a host of facilities and public spaces to one of China’s most rapidly urbanising areas

By Jonathan Bell

-

The World Monuments Fund has announced its 2025 Watch – here are some of the endangered sites on the list

The World Monuments Fund has announced its 2025 Watch – here are some of the endangered sites on the listEvery two years, the World Monuments Fund creates a list of 25 monuments of global significance deemed most in need of restoration. From a modernist icon in Angola to the cultural wreckage of Gaza, these are the heritage sites highlighted

By Anna Solomon

-

Tour Xi'an's remarkable new 'human-centred' shopping district with designer Thomas Heatherwick

Tour Xi'an's remarkable new 'human-centred' shopping district with designer Thomas HeatherwickXi'an district by Heatherwick Studio, a 115,000 sq m retail development in the Chinese city, opens this winter. Thomas Heatherwick talks us through its making and ambition

By David Plaisant

-

Raw, refined and dynamic: A-Cold-Wall*’s new Shanghai store is a fresh take on the industrial look

Raw, refined and dynamic: A-Cold-Wall*’s new Shanghai store is a fresh take on the industrial lookA-Cold-Wall* has a new flagship store in Shanghai, designed by architecture practice Hesselbrand to highlight positive spatial and material tensions

By Tianna Williams