Oscar Niemeyer’s Algerian architecture uncovered

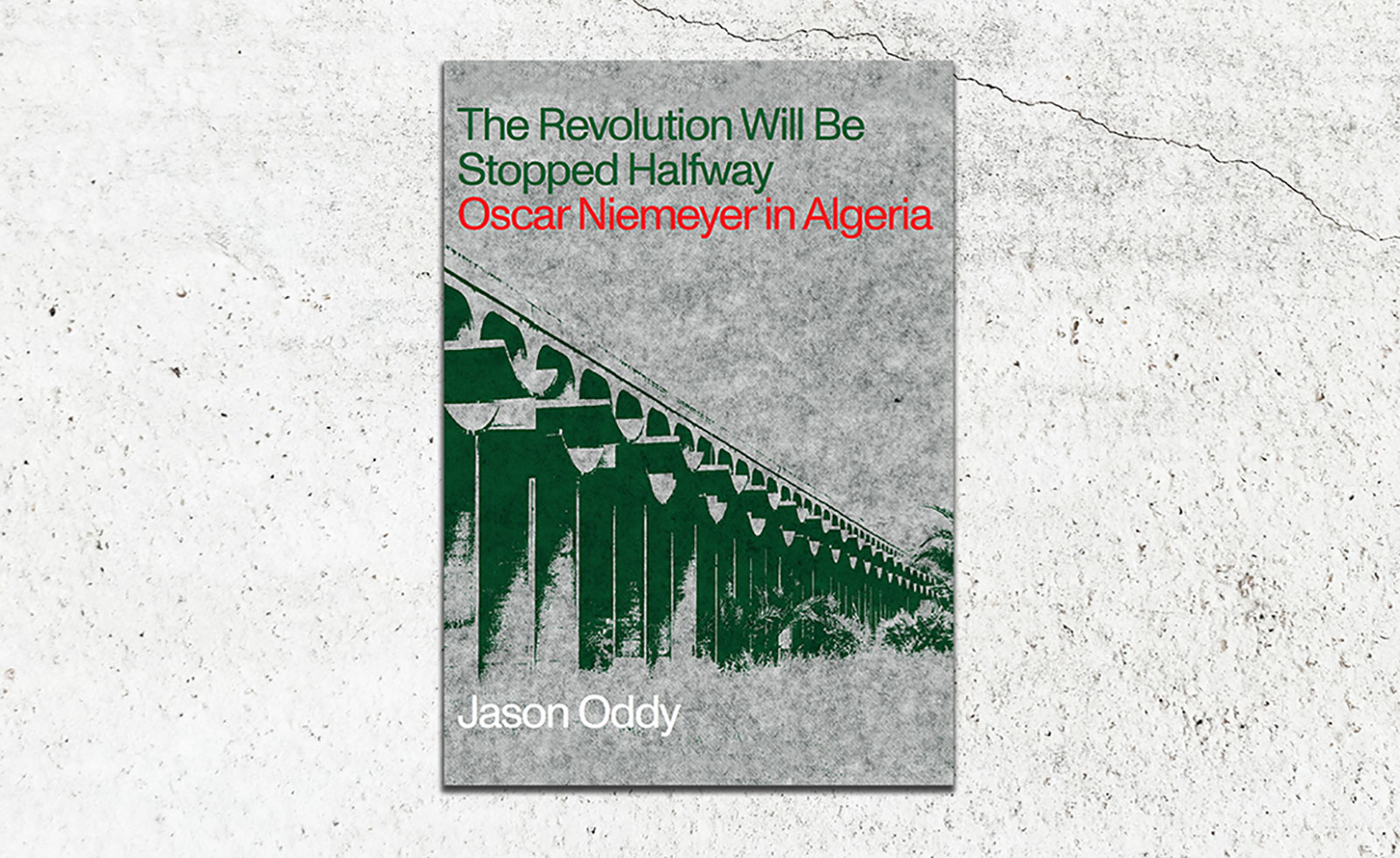

Jason Oddy’s photographic study of Oscar Niemeyer’s Algerian buildings, set alongside research and archival documents, explores the architecture’s inseparable relationship to revolutionary politics in a new book from Columbia University Press, titled The revolution will be stopped halfway: Oscar Niemeyer in Algeria

Jason Oddy

One afternoon in the British Library, Jason Oddy, photographer, artist and writer, stumbled across some Oscar Niemeyer buildings he was unfamiliar with. The sweeping curves, the volume and the story telling felt familiar, but the location – in Algeria – did not. After further research he discovered that the buildings, two universities and an Olympic-sized sports hall, were largely undocumented.

‘When Niemeyer left Brazil in 1966, after the 1964 military coup, he ended up in Paris, and then in 1968 he travelled to Algiers for the first time. He was there for six years. It’s a long time for an incredibly famous architect to be somewhere, but not that many people are aware of it,’ he tells Wallpaper*.

It was in June 1968, that Houari Boumédiène, chairman of Algeria’s Council of Revolution, socialist and hero of the recent War of Independence against France, invited Niemeyer, starchitect of Brasilia (and communist), to ‘project a new vision of Algeria to the outside world, and promote a new generation of engineers and academics.’

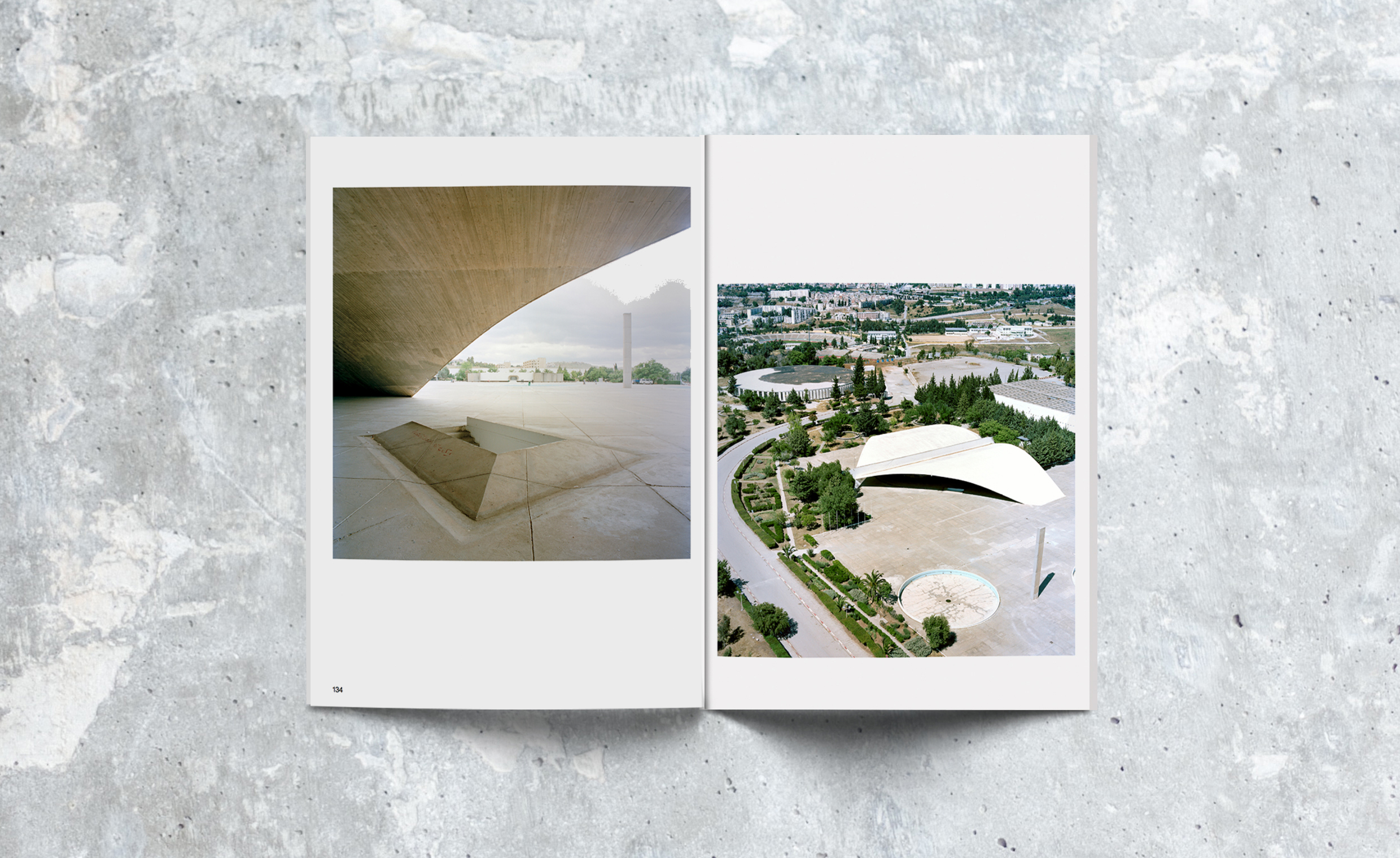

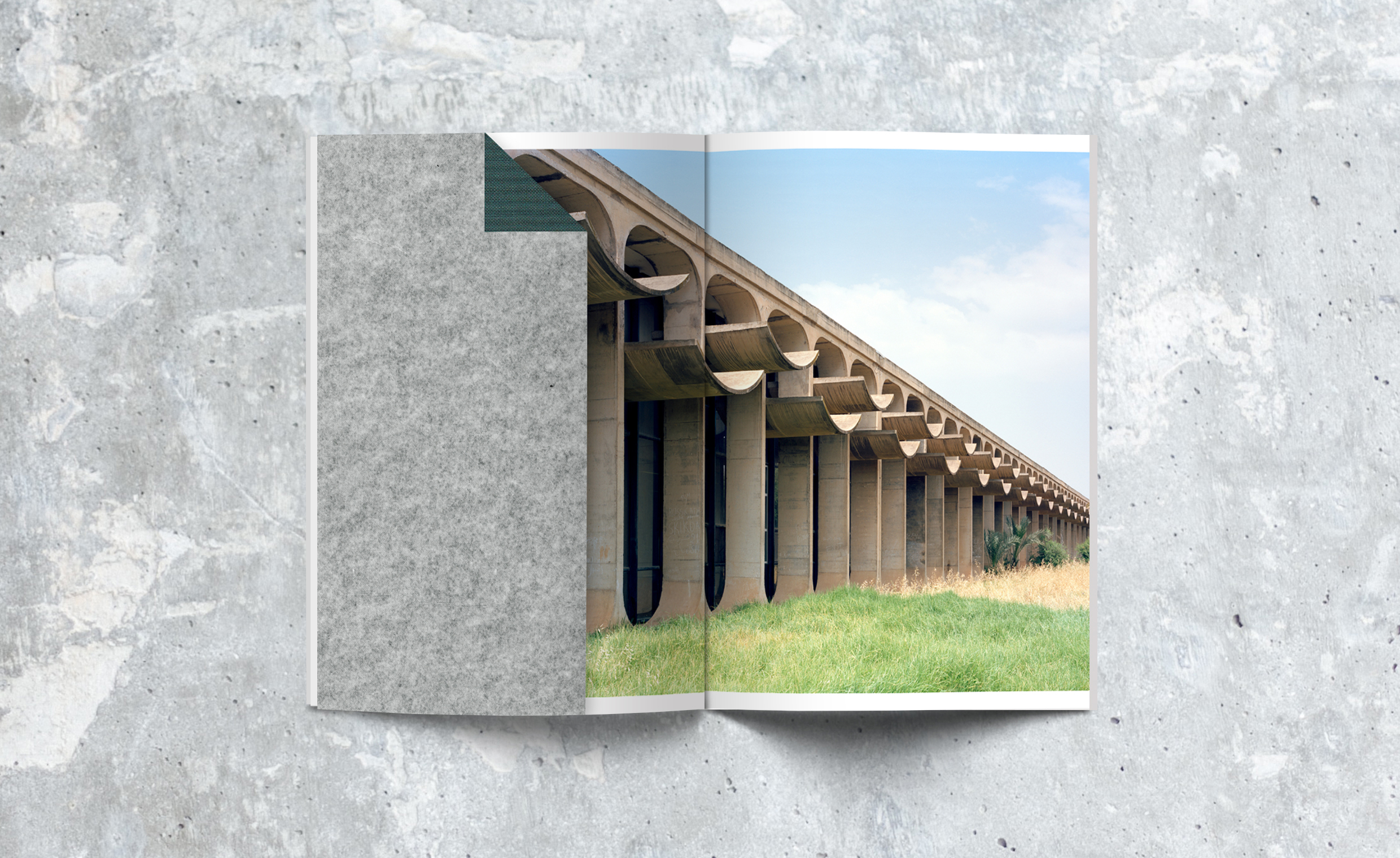

Niemeyer got started, designing the University of Constantine, with a sweeping concrete rendition of an open book supported by pilotis for the auditorium, completed in 1975. Then came the University of Science and Technology Houari Boumédiène and the Salle Omnisports known as ‘La Coupole’ for the 1975 Meditteranean Games in Algier’s Olympic Park. Each piece of architecture with their colossal open spaces and grand concrete gestures were designed to reflect Boumedienne’s socialist and militarist principles, and represent an ‘upending of the age-old order’.

‘The Village’ VI, University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene, Bab Ezzouar, Algeria, 2013

‘He was commissioned to design a whole new downtown Algiers, in the manner of Brasilia, to create a huge municipal area with a new city for residential housing for Algerians, instead of the French. He also designed, in a moment of inspiration, a new mosque, that would float off shore into the Mediterranean.’

It was an exchange between architect and commissioner that summarized the politics of this place for Oddy: ‘Your mosque is beautiful, but it is quite revolutionary,’ said Boumédiène of the design. To which Niemeyer replied, ‘It is revolutionary, but the revolution cannot be stopped halfway.’

In his essay Oddy ponders on what ‘revolution’ meant to these two revolutionaries in this exchange, and whether they were talking about architecture or politics – it is possible that neither were on the same page of this open book. Nevertheless, when Boumédiène died in 1978, all of the projects got cancelled. Hence the title of Oddy’s book: The revolution will be stopped halfway.

While designed optimistically for a democratic state, Niemeyer’s buildings also became national scars of the military ruleote here

After spending a week in Algiers in 2010, Oddy left the country with a better understanding of why the architecture had gone so undocumented. During his visit he came up against many bureaucratic barriers to photographing the government-owned buildings, and learnt more about the political history of the country, and its approach to tourism today. Unperturbed – Oddy has documented ‘the politics of place’ in some of the world’s most restricted spaces including the Pentagon, Guantanamo and a Nazi holiday resort – he spent three years pursuing permits to photograph the buildings.

On his return to Algiers, Oddy spent three weeks at the three venues, carefully documenting everything. His photographic technique, using a 5x4 inch plate camera, requires time and consideration that has become central to his style: ‘Unwieldy and slow-moving it obliges me to explore places in a measured, almost meditative way.’ And his results are therefore ‘traces of a deliberate engagement with space’.

La Coupole I, Algiers, Algeria, 2013

Oddy describes how while seeing and spending time with the architecture was extraordinary, it was also complicated. ‘These buildings are modernist treasures. Some Algerians are very proud of them, but at the same time their upkeep is not a priority,’ he says.

Algeria has had other priorities – which Samia Henni, Algerian architectural historian, outlines in her introduction ‘When Militarism meets Modernism’. After the fight for independence between 1954 – 62, during which one in 10 Algerians died, the post-colonial period was marked by revolutionary excitement, yet stagnation and corruption followed. Civil War broke out in the early 1990s between Islamists who won an election, and the military, the original vanguard of the revolution.

While designed optimistically for a democratic state, Niemeyer’s buildings also became national scars of the military rule. Archival materials documented at the end of the book document the extent of the schemes on a Brasilia-style scale that could have been – many published here for the first time. ‘It was a unique moment. A project like that could have only happened under certain circumstances and with a revolutionist vein. It had everything in it,’ says Oddy. But, unfortunately for architectural history and Niemeyer fans, the revolution was stopped half way.

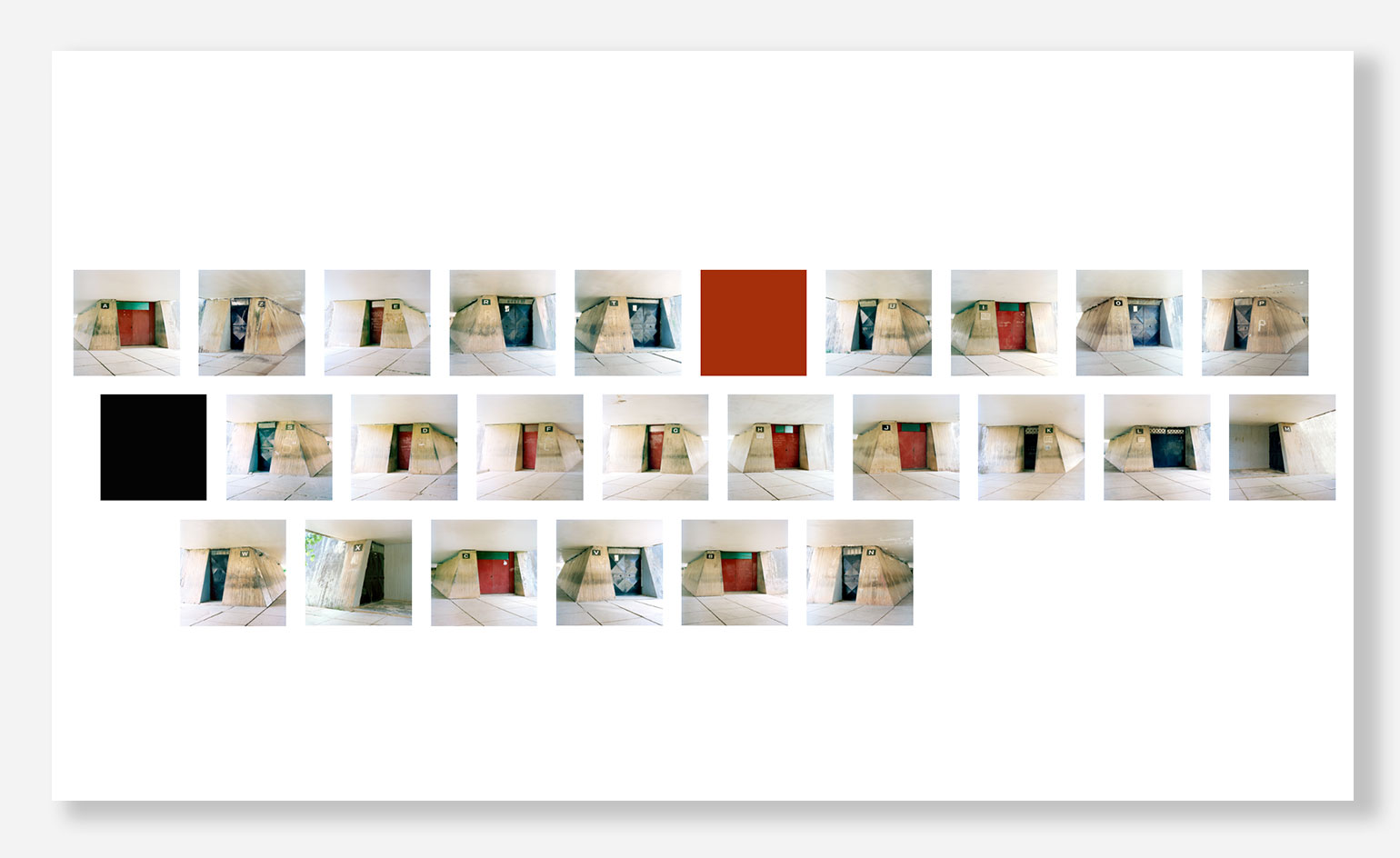

’Clavier’ by Jason Oddy – a work showing photographs of the doors of 24 identical lecture halls at the University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene, each of which bears a different letter from the Roman alphabet. Laid out in the form of a keyboard, the work raises questions about cultural, linguistic and scriptorial colonialism.

The politics of a photograph

Oddy describes the political complexity behind one of his photographs taken at the University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene:

‘I constructed this image out of a number of images. While I was walking around the campus, which is located just outside Algiers in a suburb called Bab Ezzouar, I found a whole new section that included 24 lecture halls in the shape of bunkers. At that moment, I had a sense I was stumbling across a modern ruin. There was a lot of knee-high grass growing and the concrete bunkers were emerging from the earth like sarcophagi. The whole place is very sculptural, and each of the 24 lecture halls is identified by a letter of the alphabet.

‘Why are these bunkers in a university in Algiers, designed after it had gone through a revolution and had an ‘Arabisation’ of culture, still using the Roman alphabet, the language of the colonizer? After the 150-year French rule, there was an anti-French campaign in the 60s led by one of the revolutionary figures, and then there was a further campaign in the mid-70s to Arabise the military.

‘I photographed each one of these doorways to the lecture halls, and the letters A to Z in them and I laid them out like a French keyboard. I wanted to ask the question about the status of language in the educational system, the meaning of being educated in the language of the colonizer, and how this impacts the outcomes of education on the people of Algeria.

‘Soon I began to understand that French is very much seen as the language of the upper classes, linked to privilege, and then corruption and the military state that took control of oil and gas money. The story is incredibly complex, and as an outsider it’s hard to make a rounded comment, but this is my take.’

Double page spread from the book showing two photographs by Jason Oddy of The Open Book at the University of Mentouri, Constantine, Algeria

Corridor I, University of Mentouri, Constantine, Algeria, 2013.

Opening double page spread of the book showing the Bloc des Salles de Classe at the University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene, Bab Ezzouar, Algeria

Bloc des Sciences III, University of Mentouri, Constantine, Algeria, 2013.

University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene II, Bab Ezzouar, Algeria, 2013.

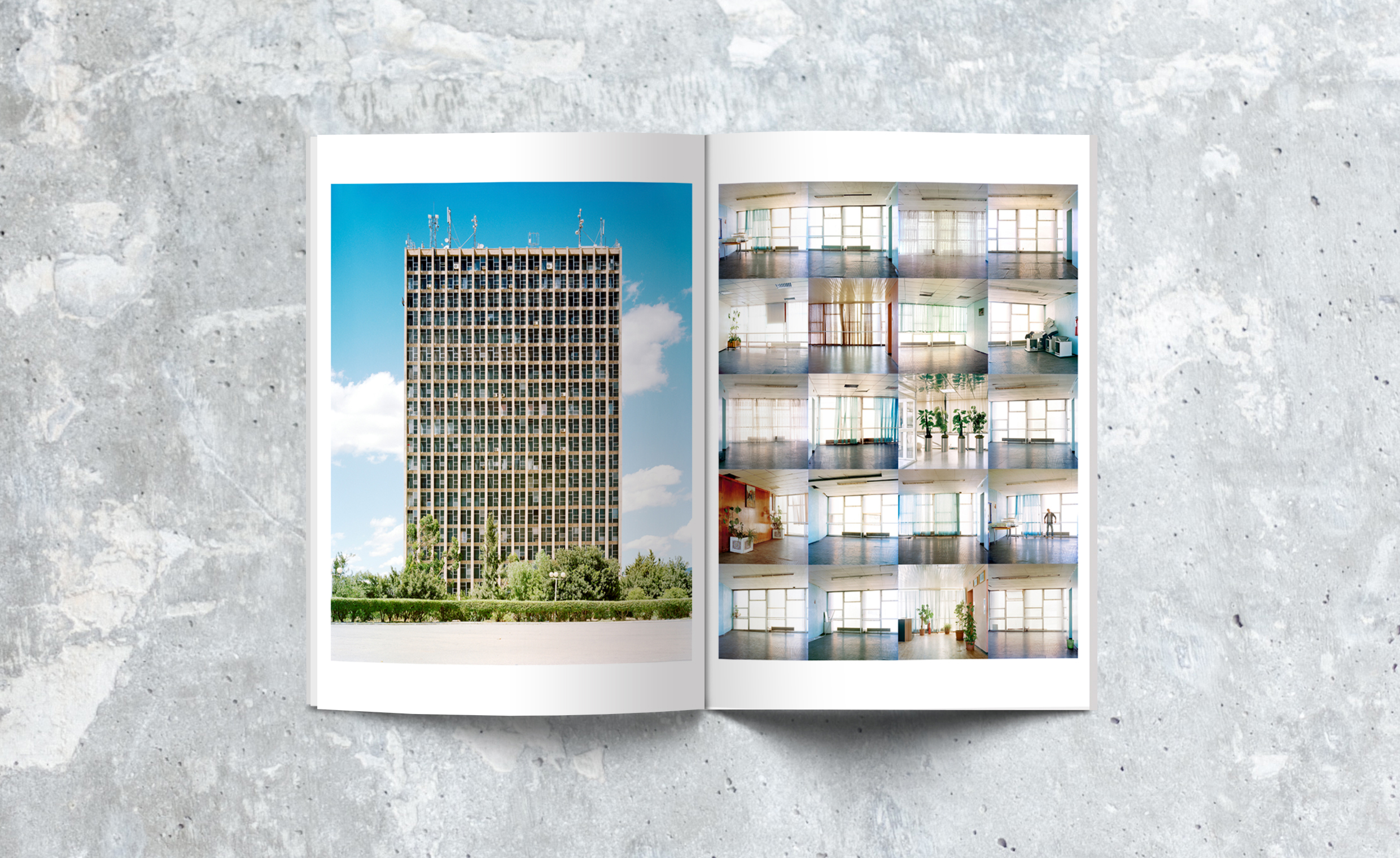

Double page spread of the book showing an exterior and a series of interior views of The Rectorate at the University of Mentouri, Constantine, Algeria

INFORMATION

The Revolution Will Be Stopped Halfway: Oscar Niemeyer in Algeria by Jason Oddy

Columbia Books on Architecture and the City

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yours

Croismare school, Jean Prouvé’s largest demountable structure, could be yoursJean Prouvé’s 1948 Croismare school, the largest demountable structure ever built by the self-taught architect, is up for sale

By Amy Serafin

-

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Jump on our tour of modernist architecture in Tashkent, UzbekistanThe legacy of modernist architecture in Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent, is explored through research, a new publication, and the country's upcoming pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025; here, we take a tour of its riches

By Will Jennings

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

By Ellie Stathaki

-

How Le Corbusier defined modernism

How Le Corbusier defined modernismLe Corbusier was not only one of 20th-century architecture's leading figures but also a defining father of modernism, as well as a polarising figure; here, we explore the life and work of an architect who was influential far beyond his field and time

By Ellie Stathaki

-

How to protect our modernist legacy

How to protect our modernist legacyWe explore the legacy of modernism as a series of midcentury gems thrive, keeping the vision alive and adapting to the future

By Ellie Stathaki

-

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st Century

A 1960s North London townhouse deftly makes the transition to the 21st CenturyThanks to a sensitive redesign by Studio Hagen Hall, this midcentury gem in Hampstead is now a sustainable powerhouse.

By Ellie Stathaki

-

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tall

The new MASP expansion in São Paulo goes tallMuseu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP) expands with a project named after Pietro Maria Bardi (the institution's first director), designed by Metro Architects

By Daniel Scheffler

-

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in France

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in FranceFondation Marta Pan – André Wogenscky: how a creative couple’s sculptural masterpiece in France keeps its authors’ legacy alive

By Adam Štěch