Brutalism’s unsung mecca? The Philippines

Philippine brutalism is an architecture subgenre to be explored and admired; the brains and lens behind visual database Brutalist Pilipinas, Patrick Kasingsing, takes us on a tour

Philippine brutalism is having a quiet revival. Brutalist architecture and concrete finishes are in vogue again. Walls are being left unpainted – on purpose! Buildings once dismissed as eyesores are now showing up in fashion shoots, Reels, and mood boards. Brutalist merch – maps, posters, even polo shirts – are flying off the shelves. The ‘aesthetic’ has drawn a new generation of fans to its clarity, rawness, and refusal to decorate.

GSIS Complex

What is Filipino Brutalism?

But brutalism is not a style in the traditional sense. It is an architectural response borne out of post-war urgency – a global push to rebuild fast, affordably, and together. In the Philippines, it aligned with post-independence momentum. Concrete, introduced by American colonisers, was practical: durable, available, and suited to the realities of our climate and level of seismic activity. The material was first used in neoclassical government buildings and quickly spread across civic and commercial spaces after the war.

PICC Courtyard with Arturo Luz's Anito Sculpture

A brief history of Philippine brutalism

From the 1940s to the 1960s, Filipino architects travelled far and wide, exchanging ideas and tuning in to global modernist architecture. In the United States, National Artist for Architecture Leandro Locsin saw Paul Rudolph’s concrete work first-hand and resolved to make it his material. José Maria Zaragoza absorbed Niemeyer’s sensuous take on concrete in Brazil. A local take on Brutalism followed: tropical, experimental, and expressive.

Ramon Magsaysay Center

The style peaked from the 1950s to the 1980s, tracking with post-war growth and, eventually, the Marcos regime. Under martial law, Brutalism was co-opted into state architecture: heavy, imposing, and unyielding. By the ’90s, its image had worn thin locally and abroad. Postmodernism took over: concrete was out, colour was in. Still, the buildings remain. Some are preserved, others are neglected or gone.

With all its polarising history, brutalism is back in the public consciousness and is worth taking a second look at. The list below isn’t comprehensive (and is, regrettably, Manila-centric). Still, it offers a cross-section of how Brutalism took root in our tropical context, how it was adapted, politicised, and ultimately became ingrained in the Philippines’ cultural and architectural narrative.

7 Filipino brutalist buildings

Several buildings still standing in Manila and beyond express this boldest of architecture movements. Here, we explore seven of Philippine brutalism's key highlights in a whistle-stop tour of the genre in the country.

Tanghalang Pambansa (National Theatre)

Where: CCP Complex, Pasay City

Architect: Leandro Locsin

When: 1969

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Likely the first building that comes to mind in any local conversation on brutalism in the country. Its silhouette is Philippine brutalism at its most elegant and acrobatic: a travertine block ‘floats’ above a reflecting pool, approached by a sweeping concrete ramp used by theatregoers and weekend joggers. Known for its impeccable acoustics and striking concrete interiors, age has started to make its mark on the National Theatre, which is currently closed for a long-overdue renovation.

Philippine International Convention Center (PICC)

Where: CCP Complex, Pasay City

Architect: Leandro Locsin

When: 1976

Built in just 23 months for the 1976 IMF–World Bank meetings, the 12-hectare PICC was Asia’s first international convention centre when it opened. A more dramatic take on Locsin’s floating mass, first seen in the National Theater, the PICC is a daring showcase for a workmanlike material—concrete pushed to its formal and spatial extremes. Beyond hosting large-scale events, it has cemented its place in local culture as a graduation stage for select universities and the go-to venue for oath-taking ceremonies.

The Peninsula Manila

Where: Makati City

Architect: Gabriel Formoso

When: 1976

A landmark hotel that has hosted everything from a turn-of-the-millennium concert to an attempted coup, The Peninsula Manila has seen its share of history from behind its corduroy concrete walls. Opened in 1976 for the IMF–World Bank meetings, it was envisioned as a tropical hotel in the city: a concrete pedestal supporting two wings of rhythmic pillars and deep overhangs, originally anchored by a brutalist fountain of lush greenery and cascading water. The fountain was regrettably replaced in the ’90s with a kitschy neoclassical number.

The Makati Stock Exchange (MSE) Building

Where: Makati City

Architect: Leandro Locsin

When: 1977

Mr. Locsin’s command of concrete earns him a third (but not final) spot on this list. Designed as a stylistic template for a rising business district, the Makati Stock Exchange is both svelte and imposing—a sandwich of wafer-thin volumes lined with concrete sun baffles. The stock exchange has since moved to larger digs, but this early office building—set along what was once the runways of the country’s first commercial airport—still holds its own against newer, taller neighbours around the Ayala Triangle Gardens.

St. Andrew the Apostle Church

Where: Makati City

Architect: Leandro Locsin

When: 1968

Concrete takes on a fabric-like quality in this Bel-Air church by Locsin – tentlike in form, supported by two interlocking pillars forming an X, alluding to the crucifixion of the apostle it’s named after. From above, the floor plan resembles a butterfly, with two wings of curved pews radiating from a suspended copper cross by fellow National Artist Vicente Manansala.

Pacific Machines Building

Where: City of San Juan

Architect: Antonio Heredia

When: 1975

Dubbed the 'Brutalist KFC' online, the Pacific Machines Building by Antonio Heredia has lived many lives over its 50-year history, all under the same company that commissioned it. One of the earliest structures along this stretch of EDSA, its blocky, interlocking wedges were said to resemble typewriters, which the company once sold. As it began leasing space, the building’s raw concrete exterior took on different liveries: blue and yellow for an automobile association that also cut out a new front entrance, and now red and grey for KFC. Though the company still occupies part of the building, recent listings suggest the property may soon be up for sale.

Sunken Shrine of Cabetican

Where: Cabetican, Bacolor

Architect: Engineer Julio Macapal and seven unnamed architects

When: 1985

Our only non-Manila entry earns its spot for both form and story. The Sunken Shrine of Cabetican is, quite literally, a sunken church – buried under six meters of lahar, leaving only a third of its original 20+-meter height exposed. Its origins remain unclear; in 2005, the surrounding community excavated an entryway and reopened the wedge-shaped chapel. The only way in for a time was through meter-tall gaps surrounding the church, forcing visitors to kneel. Inside, a cavernous concrete ceiling rises to a half-moon oculus that lights a striking Lourdes grotto-inspired retablo. Recent renovations have eased access and helped guard the interior from regular flooding.

Patrick Kasingsing is an art director, photographer, writer, and Philippine architectural heritage advocate. He founded @brutalistpilipinas and @modernistpilipinas, platforms celebrating the country’s architectural legacy, and launched Kanto.PH, an online magazine covering design and culture in Southeast Asia. Previously creative director of architecture magazine BluPrint, he helped revitalized its identity and oversaw creative direction for five One Mega Group titles. As art director of advertising title adobo magazine, his contributions to its rebrand earned a Philippine Quill award. Patrick’s writing and photography has appeared in publications from Birkhäuser, Braun, DOM Publishers, and Vogue Philippines among others.

-

Bowers & Wilkins has updated its Px7 wireless headphones. We give them a listen

Bowers & Wilkins has updated its Px7 wireless headphones. We give them a listenThe new Bowers & Wilkins Px7 S3 bring audio expertise and new technology to an updated and enhanced version of its excellent noise-cancelling headphones

By Jonathan Bell

-

Our pick of the reveals at the 2025 New York Auto Show, from concept SUVs to new EVs

Our pick of the reveals at the 2025 New York Auto Show, from concept SUVs to new EVsInterest in overseas brands remained strong at this year’s NY Auto Show despite the threat of tariffs designed to boost American-owned brands

By Shawn Adams

-

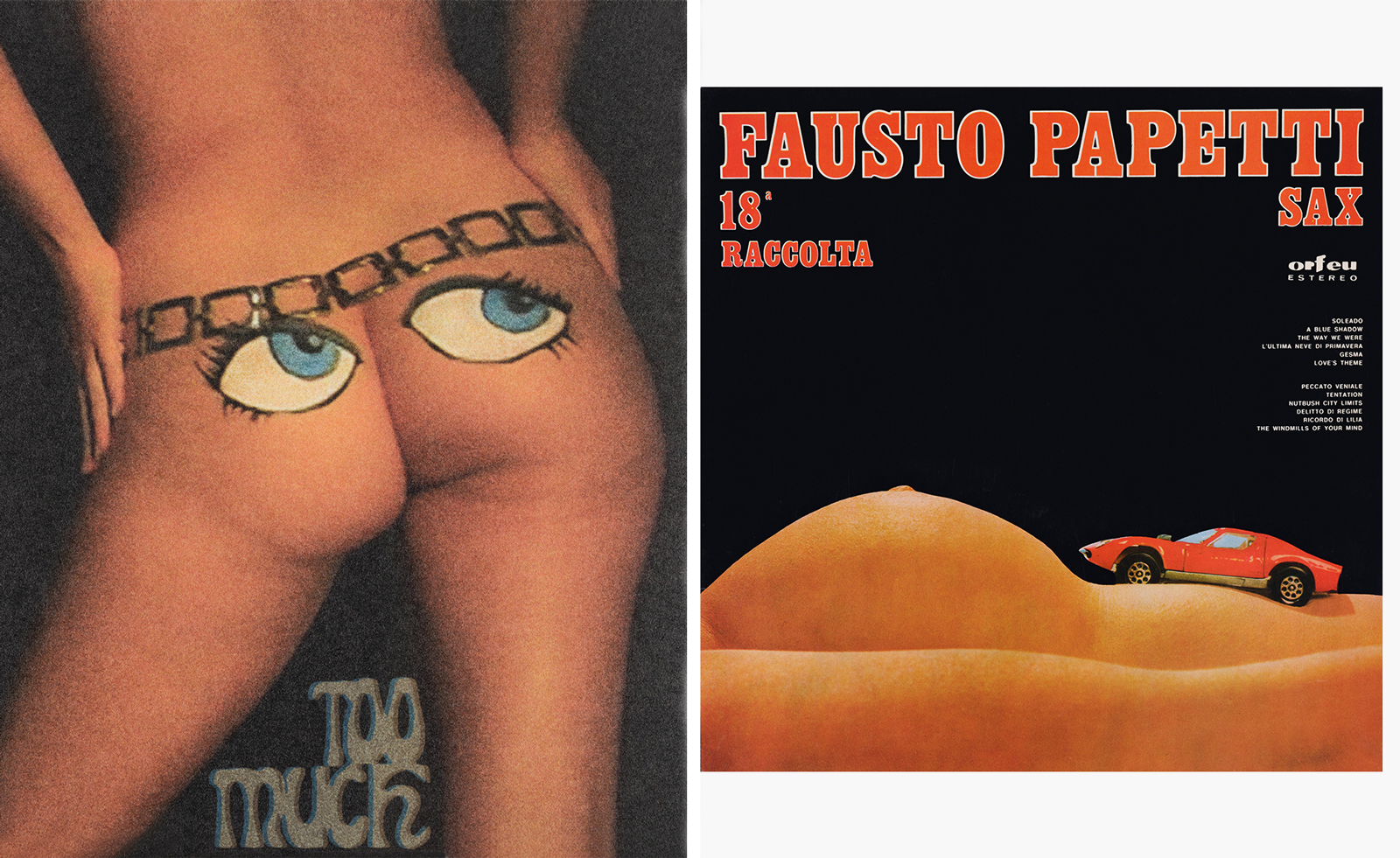

Taschen’s sexy record covers are hitting all the right notes

Taschen’s sexy record covers are hitting all the right notesTaschen has been through 50 years of album art for its latest tome, ‘Sexy Record Covers’

By Hannah Silver

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

By Ellie Stathaki

-

A Medellin house offers art, brutalism and drama

A Medellin house offers art, brutalism and dramaA monumentally brutalist, art-filled Medellin house by architecture studio 5 Sólidos on the Colombian city’s outskirts plays all the angles

By Rainbow Nelson

-

The best brutalism books to add to your library in 2025

The best brutalism books to add to your library in 2025Can’t get enough Kahn? Stan for the Smithsons? These are the tomes for you

By Tianna Williams

-

Brutalist bathrooms that bare all

Brutalist bathrooms that bare allBrutalist bathrooms: from cooling concrete flooring to volcanic stone basins, dip into the stripped-back aesthetic with these inspiring examples from around the world

By Tianna Williams

-

Space House: explore the brutalist London landmark’s new chapter

Space House: explore the brutalist London landmark’s new chapterSpace House, a landmark of brutalist architecture by Richard Seifert & Partners in London’s Covent Garden, is back following a 21st-century redesign by Squire & Partners and developer Seaforth Land

By Ellie Stathaki

-

‘Concrete Dreams’: rethinking Newcastle’s brutalist past

‘Concrete Dreams’: rethinking Newcastle’s brutalist pastA new project and exhibition at the Farrell Centre in Newcastle revisits the radical urban ideas that changed Tyneside in the 1960s and 1970s

By Smilian Cibic

-

Soviet brutalist architecture: beyond the genre's striking image

Soviet brutalist architecture: beyond the genre's striking imageSoviet brutalist architecture offers eye-catching imagery; we delve into the genre’s daring concepts and look beyond its buildings’ photogenic richness

By Edwin Heathcote

-

Is Rochester Street Office a creative worker’s dream? Inside a Sydney workspace echoing calmness and light

Is Rochester Street Office a creative worker’s dream? Inside a Sydney workspace echoing calmness and lightRochester Street Office by Allied_Office merges utilitarian design with cascading vegetation, presenting a thriving environment for creativity and collaboration

By Tianna Williams