Pomo erectus: a perfectly aged temple to wine and architecture

Napa Valley’s Clos Pegase Winery celebrates its 30th birthday this year, just as a new biography of its architect, the late American postmodernist Michael Graves, is released. Graves was one of 20th-century architecture’s mavericks, a young modernist – one of the legendary ‘New York Five’, no less – who turned his back on the evolutionary approach of his peers to explore the less po-faced facets of architectural design. This populist approach was galvanised by product design for the likes of Alessi, Target and JCPenney, for whom Graves designed playful bestsellers that made him one of the era’s most commercially accessible designers.

Before Target and Alessi, Graves’ work was considered perverse, iconoclastic and provocative, deliberately out of step with prevailing taste. The Clos Pegase is a case in point. Riding on the tails of the then new fashion for architect-designed wineries, the project was won in a competition run by SFMOMA. Graves and his team drew up a romantic vision of a Bacchanalian temple, transporting Tuscan vistas and the mysterious landscapes of Poussin and Lorrain to the Northern Californian hills.

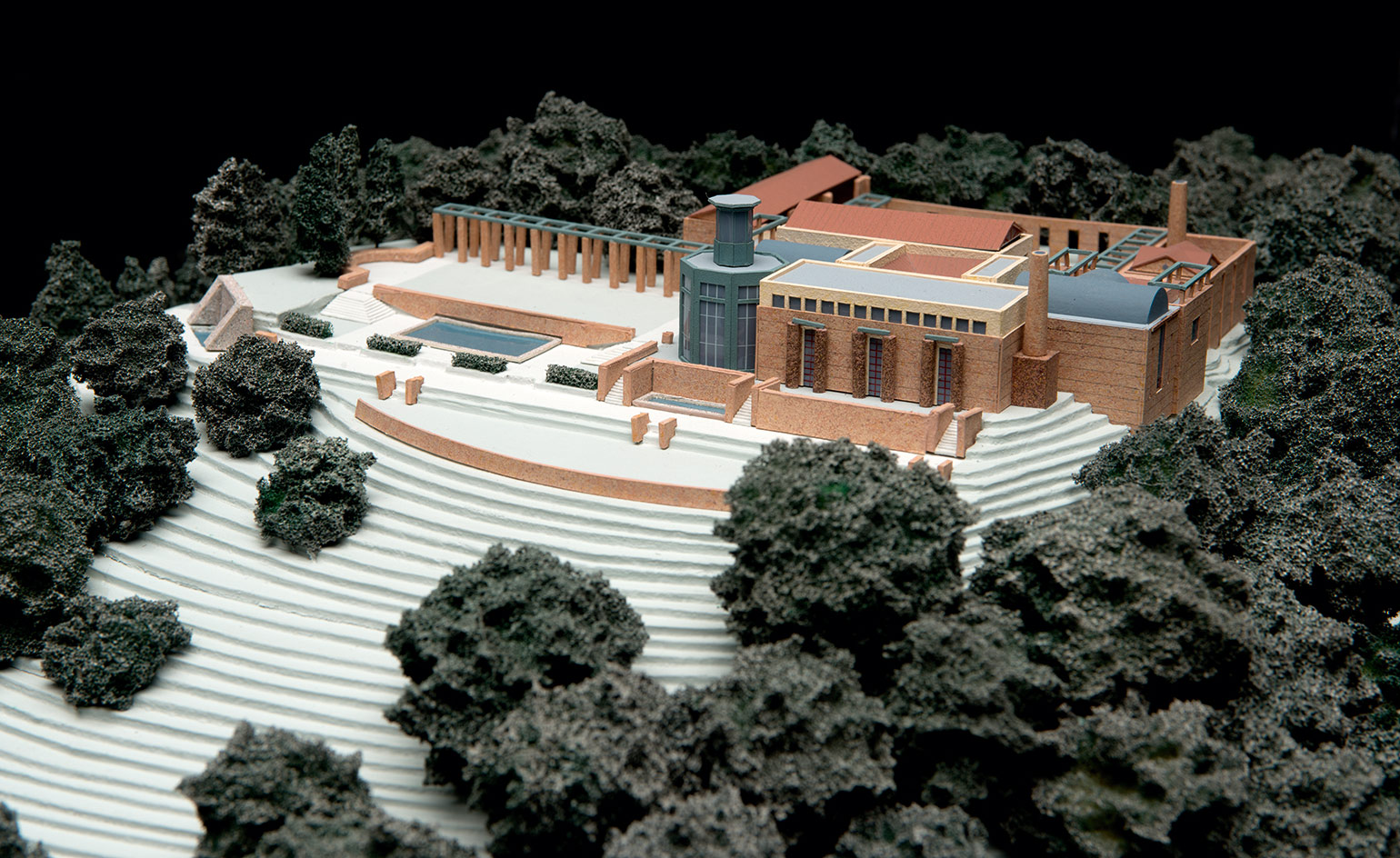

The brief called for a small Napa Valley fiefdom, with public tasting rooms, winemaking areas and bottle storage along with a private villa for the owner, publisher and art collector Jan Shrem. Named after one of Shrem’s favourite paintings of Pegasus by the French symbolist Odilon Redon, the complex was conceived with a sculpture park and murals by Graves and the contemporary neoclassicist Edward Schmidt. A key unrealised feature was the ‘mountain of Pegasus’, a circular amphitheatre-like structure off which walks and vistas through the vineyard were to radiate. The idea was to evoke the habitat of the legendary creature, which was said to have opened up springs simply by touching the earth with its hoof.

One of Graves' studies for the entrance portico. Photography: Courtesy of Michael Graves Architecture & Design/Clos Pegase - Otto Baitz

‘This kind of mythological storytelling was a favourite of Michael’s at the time – he had a similar backstory for the Swan and Dolphin Hotels [at Walt Disney World in Florida],’ says Ian Volner, author of the new monograph, Michael Graves: Design for Life ($30, Princeton Architectural Press). The winery programme was eventually scaled back and the mountain lost, but Graves maintained the grand axis, using the heightened perspective created by rows of vines to focus on a classically symmetrical structure, whose geometric façades sheltered a generous courtyard – the ‘clos’ – described in 1987 by the New York Times critic Paul Goldberger as ‘a gateway to the mountains’.

‘Formally, it is composed of the very specific PoMo kit of parts Graves had first realised in his 1980 Venice Biennale installation,’ Volner explains. ‘The ellipse, like an exaggerated [semi-circular] Diocletian window; the faux rustication in the painting program; the repetition of Roman lattices, columnar volumes...’ The New York-based writer met Graves many times, and the book was initially planned as a ‘collaborative memoir’. Graves’ death in 2015, at the age of 80, turned it into a biography with input from clients, critics and collaborators.

Clos Pegase still holds a fascination. It is a building with a narrative, not just about the wine-making process, but about the power of architecture to command and transform its surroundings. Ultimately, however, the stylistic and academic nuances of the era have been blurred by distance and skewed by knowledge of Graves’ commercial acumen and sense of fun – this is the man who used the Seven Dwarfs as caryatids on Disney’s Michael D Eisner Building. The marriage of pop culture and commerce is rarely so considered. Shrem sold up in 2012, but the winery retains its playful mystery, out of time from the moment it was built.

As originally featured in the December 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*225)

A model of the winery, which features a long colonnade, lantern-like tower and tapered chimneys

Wooden barrels in the fermentation shed

INFORMATION

Michael Graves: Design for Life, $30, published by Princeton Architectural Press. For more information, visit the Close Pegase website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Toklas’ own-label wine is a synergy of art, taste and ‘elevated simplicity’

Toklas’ own-label wine is a synergy of art, taste and ‘elevated simplicity’Toklas, a London restaurant and bakery, have added another string to its bow ( and menu) with a trio of cuvées with limited-edition designs

By Tianna Williams

-

Château Galoupet is teaching the world how to drink more responsibly

Château Galoupet is teaching the world how to drink more responsiblyFrom reviving an endangered Provençal ecosystem to revisiting wine packaging, Château Galoupet aims to transform winemaking from terroir to bottle

By Mary Cleary

-

London’s most refreshing summer cocktail destinations

London’s most refreshing summer cocktail destinationsCool down in the sweltering city with a visit to London’s summer cocktail destinations

By Mary Cleary

-

Learn how to curate a simple cheese board with perfect port pairings

Learn how to curate a simple cheese board with perfect port pairingsThe experts at artisan cheesemonger Paxton & Whitfield share tips for curating a simple but sophisticated cheese board, with port and cheese pairings for every taste

By Melina Keays

-

IWA sake brewery by Kengo Kuma is Best Roofscape: Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

IWA sake brewery by Kengo Kuma is Best Roofscape: Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022IWA sake brewery in Japan, by Kengo Kuma & Associates, scoops Best Roofscape at the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

By Tony Chambers

-

The Chuan Malt Whisky Distillery by Neri & Hu offers a twist on Chinese tradition

The Chuan Malt Whisky Distillery by Neri & Hu offers a twist on Chinese traditionNeri & Hu designs headquarters for The Chuan Malt Whisky Distillery in China's Sichuan province

By Yoko Choy

-

St Pancras Renaissance Hotel opens Booking Office 1869 restaurant

St Pancras Renaissance Hotel opens Booking Office 1869 restaurantBooking Office 1869 restaurant, at the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel, is set to become a new London hotspot. Developer Harry Handelsman and designer Hugo Toro tell us about its creation

By Mary Cleary

-

Sweet Sauternes: France’s forgotten wine gets a reputational makeover

Sweet Sauternes: France’s forgotten wine gets a reputational makeoverSaskia de Rothschild is on a mission to revive the popularity of Sauternes white wine, with Rieussec, produced and packaged with a fresh, more sustainable approach

By Mary Cleary