A walk through Potsdamer Platz: Europe’s biggest construction site 30 years on

In 2024, Potsdamer Platz celebrates its 30th anniversary and Jonathan Glancey reflects upon the famous postmodernist development in Berlin, seen here through the lens of photographer Rory Gardiner

The first buildings of Berlin’s born-again Potsdamer Platz opened 30 years ago. Largely complete by 2000, this ambitious urban development, a kilometre south of the Brandenburg Gate, had been Europe’s biggest construction site. How big? One hundred and fifty acres. Think of Potsdamer Platz as more or less the size of 50 Trafalgar Squares or 30 Midtown Manhattan blocks. Half as big again as London’s towering Canary Wharf and almost as big as Beijing’s Forbidden City.

Aerial overview of part of the Potsdamer Platz today

A walk through Potsdamer Platz

How could such a big, jigsaw piece of a major European city have ever gone missing? What happened to the old Potsdamer Platz between its bright-lights 1930s heyday and the 1990s? What is the new Potsdamer Platz like 30 years on? Daniel Libeskind, the architect of Berlin’s radical Jewish Museum, which opened in 2001, said around the time of the development's completion: 'Potsdamer Platz is an example of how you can hire the best architects in the world and still not automatically end up with something great.' Proficient, that is, if a little soulless.

The Daimler Chrysler office and retail building by Richard Rogers

The buildings rising here from the early 1990s on four commercially developed plots were designed by, among others, Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, Hans Kollhoff, Helmut Jahn, Arata Isozaki and Rafael Moneo, all distinguished architects. The quality of construction is high, with generous use of terracotta, brick and sandstone cladding. The development also features sustainability elements that were ahead of their time, such as green roofs and the recycling of rainwater into urban pools to lower the environmental temperature. The Sony Centre, designed by the Chicago architect Helmut Jahn, has a dramatic, circus-like quality, its eight buildings sharing a dramatic vaulted roof stretched between them. There is public art galore. Frank Stella. Robert Rauschenberg. Jeff Koons.

Part of the Renzo Piano Building Workshop-designed masterplan

Here is also Dunkin’ Donuts, Pret a Manger, KFC, the Legoland Discovery Centre and The Upside Down, 'Berlin’s first interactive social media museum'. On any day of the week, tourists parade in their tens of thousands. In other words, Potsdamer Platz is an interesting port of call for daytrippers, students and fans of 1990s commercial architecture and urban planning, and it remains an important site of Berlin's reunification and a powerful place in European history.

Entrance to one of the Potzdamer Platz underground train stations

It is also an important case study for those keen to understand the effects of the privatisation of public space. At the time of its development, the large-scale scheme was controversial for bringing a commercially led attitude to a historically sensitive and central part of the city. Even with its high footfall, the development can feel detached from the city proper.

Mercedes-Benz Headquarters by Rafael Moneo

It was always going to be a challenge to re-establish what had been a No Man’s Land for many decades. Photographs, films and recollections of Potsdamer Platz between the two world wars reveal how it was once an essential and decidedly lively part of an energetic and cultured city that lost its way, along with its very fabric and thousands of its citizens, as Nazi Germany went to war in 1939.

Landscaping outside the Daimler Chrysler building

What had been an 18th-century military parade ground morphed into Berlin’s version of Times Square or Piccadilly Circus, albeit on a much bigger scale, criss-crossed by trams and, below ground, by U-bahn and S-bahn trains, and flanked by grand department stores, Neo-Baroque embassies and government offices, nightclubs, neon lights and a general sense that all modern life was here.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The Kollhoff Tower by Hans Kollhoff

In 1933, as Martin Wagner, the chief city architect, drew up plans to completely reconstruct Potsdamer Platz in a modern style, the Expressionist architect Erich Mendelson completed his ultra-modern, multi-use Columbushaus on one side of the great square. Remarkably, Columbshaus survived the Second World War only to be gutted by fire and then demolished with the coming of the Wall and No Man’s Land on either side.

Daimler Chrysler Residential complex by Richard Rogers

Since the reunification of Berlin and Germany in 1990, a debate had raged as to how the city should be rebuilt. One solution was Potsdamer Platz, vilified for bringing commercially driven development and privatised public space into the heart of an old European city. Compared, though, to many later such schemes around the world, it can still look remarkably refined and restrained – an outlying, unexpected sample of 1990s architecture.

Jonathan Glancey is a journalist, author and broadcaster. He has been Architecture and Design Correspondent of the Guardian and Architecture and Design Editor of the Independent. He began his career with the Architectural Review. He is currently writing Architecture + Flight with Norman Foster, Where we Live, a study of the art of British house building, and Operation Bowler, a story of Venice during the Second World War.

-

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling works

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling worksIn an exhibition at Soft Opening, London, Shannon Cartier Lucy revisits childhood memories

-

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friends

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friendsInspired by artist Sophie Calle, Colleen Kelsey’s ‘Wearing It Out’ sees the writer ask ten friends to tell the stories behind their most precious garments – from a wedding dress ordered on a whim to a pair of Prada Mary Janes

-

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan Bell

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan BellWhat were our chosen conveyances in 2025? These ten cars impressed, either through their look and feel, style, sophistication or all-round practicality

-

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna Doshi

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna DoshiDoshi Retreat opens at the Vitra campus, honouring the Indian modernist’s enduring legacy and joining the Swiss design company’s existing, fascinating collection of pavilions, displays and gardens

-

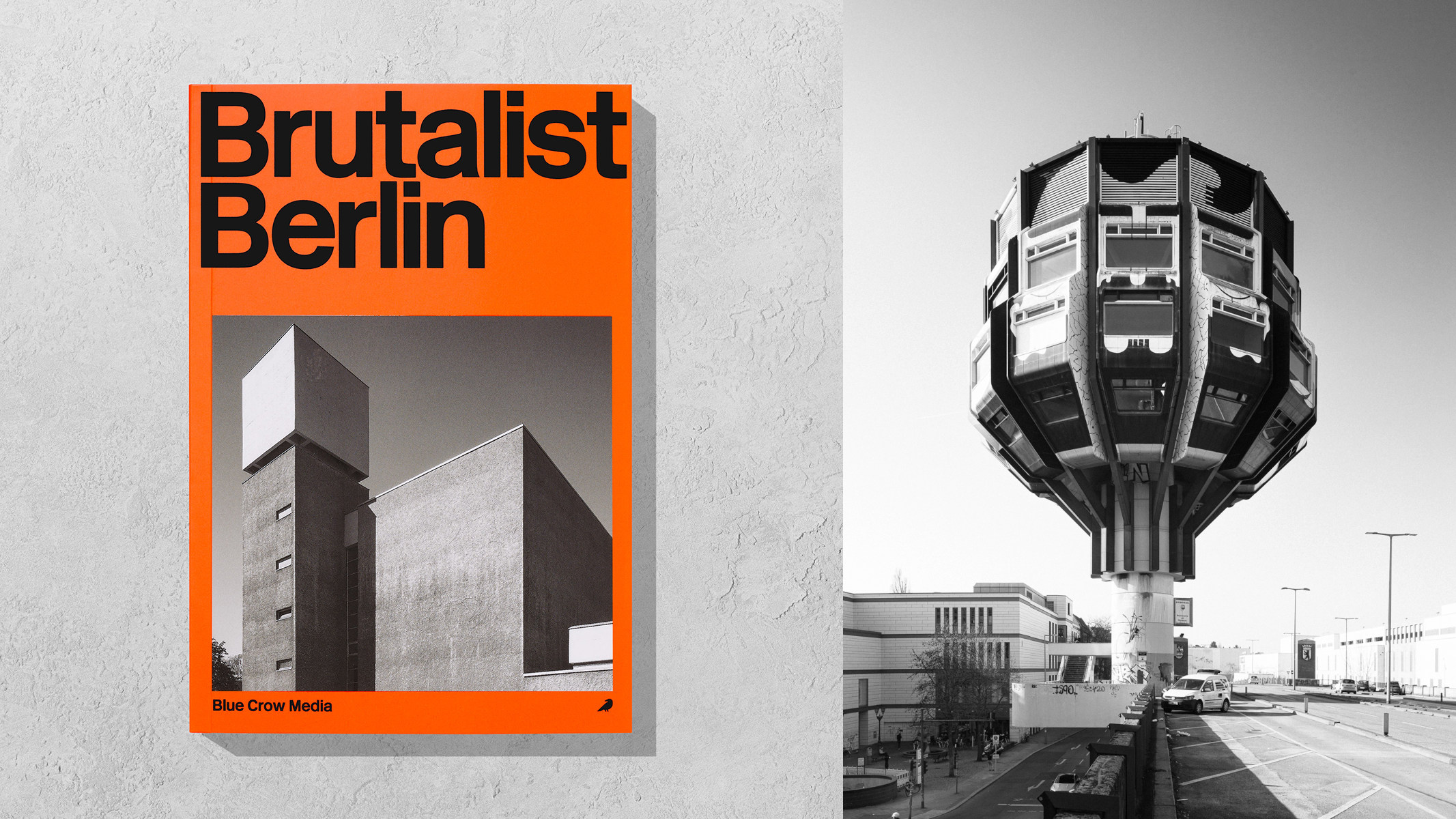

‘Brutalist Berlin’ is an essential new guide for architectural tourists heading to the city

‘Brutalist Berlin’ is an essential new guide for architectural tourists heading to the cityBlue Crow Media’s ‘Brutalist Berlin’ unveils fifty of the German capital’s most significant concrete structures and places them in their historical context

-

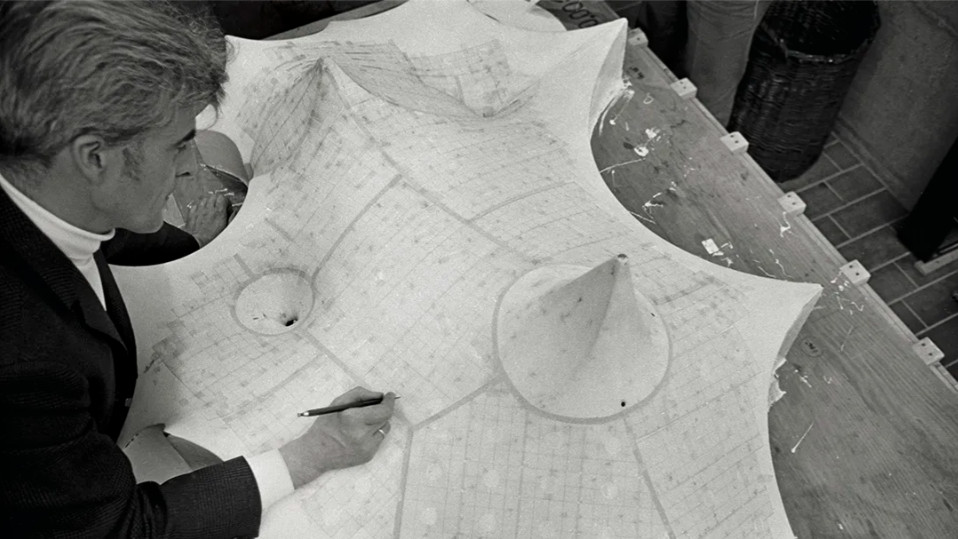

A new book delves into Frei Otto’s obsession with creating ultra-light architecture

A new book delves into Frei Otto’s obsession with creating ultra-light architecture‘Frei Otto: Building with Nature’ traces the life and work of the German architect and engineer, a pioneer of high-tech design and organic structures

-

What is Bauhaus? The 20th-century movement that defined what modern should look like

What is Bauhaus? The 20th-century movement that defined what modern should look likeWe explore Bauhaus and the 20th century architecture movement's strands, influence and different design expressions; welcome to our ultimate guide in honour of the genre's 100th anniversary this year

-

Step inside Clockwise Bremen, a new co-working space in Germany that ripples with geological nods

Step inside Clockwise Bremen, a new co-working space in Germany that ripples with geological nodsClockwise Bremen, a new co-working space by London studio SODA in north-west Germany, is inspired by the region’s sand dunes

-

Join our world tour of contemporary homes across five continents

Join our world tour of contemporary homes across five continentsWe take a world tour of contemporary homes, exploring case studies of how we live; we make five stops across five continents

-

A weird and wonderful timber dwelling in Germany challenges the norm

A weird and wonderful timber dwelling in Germany challenges the normHaus Anton II by Manfred Lux and Antxon Cánovas is a radical timber dwelling in Germany, putting wood architecture and DIY construction at its heart

-

A Munich villa blurs the lines between architecture, art and nature

A Munich villa blurs the lines between architecture, art and natureManuel Herz’s boundary-dissolving Munich villa blurs the lines between architecture, art and nature while challenging its very typology