Paris’ architecturally fascinating Villejuif-Gustave Roussy metro station is now open

Villejuif-Gustave Roussy is part of the new Grand Paris Express, a transport network that will raise the architectural profile of the Paris suburbs

The end of January marked the inauguration of the Villejuif-Gustave Roussy station in the French capital. The station sits on the Grand Paris Express – a metro network that links the suburbs without crossing Paris, which began construction in 2016. The project will deliver 200 km of automated metro and 68 stations by 2030, making it the largest infrastructure project currently being undertaken in Europe.

The station, which will serve over 100,000 passengers per day, was designed by architect and urban planner Dominique Perrault, and is one of the most impressive within the Grand Paris Express. For one, its 50-metre depth makes it one of Europe's deepest transport infrastructures.

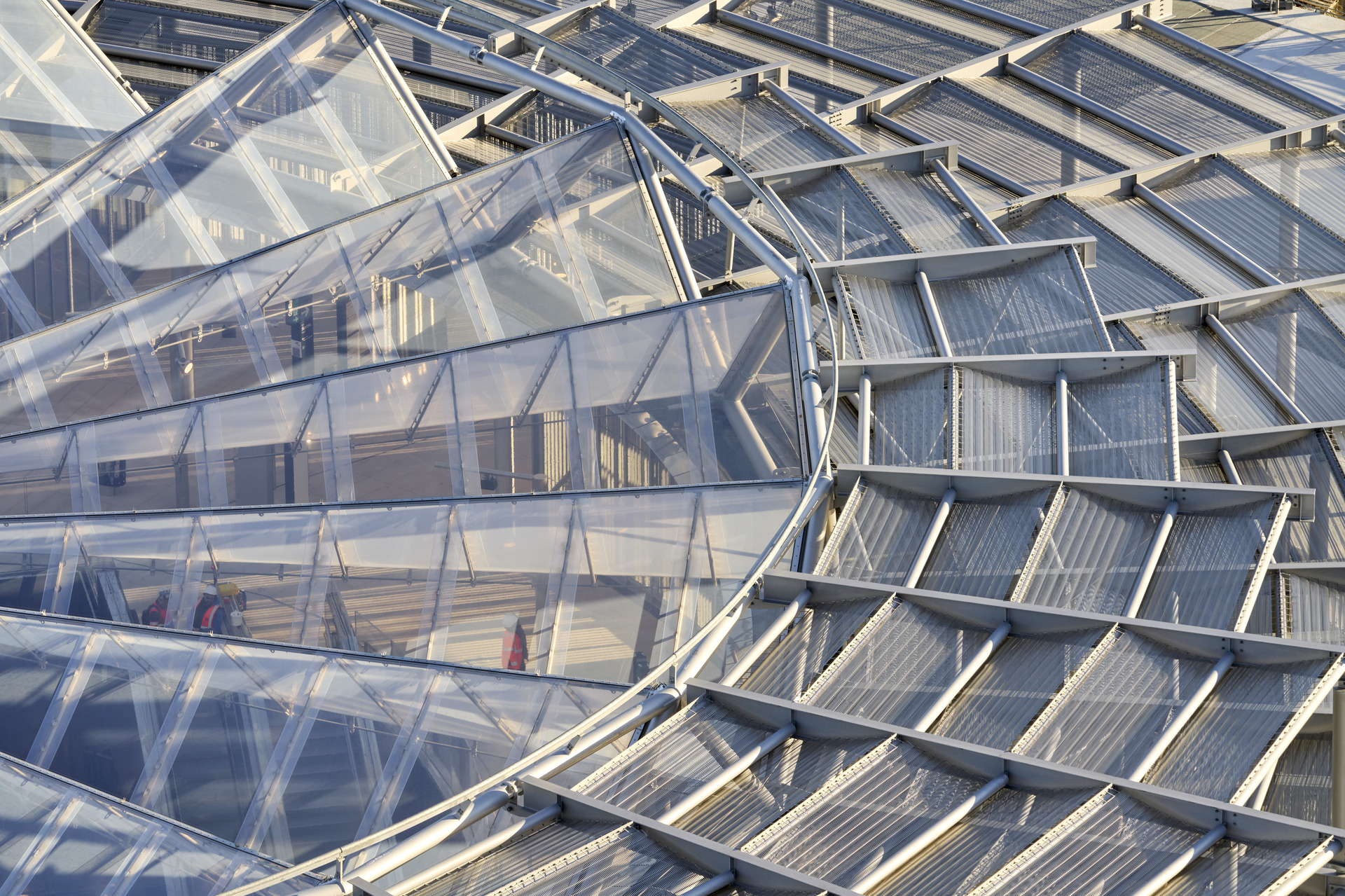

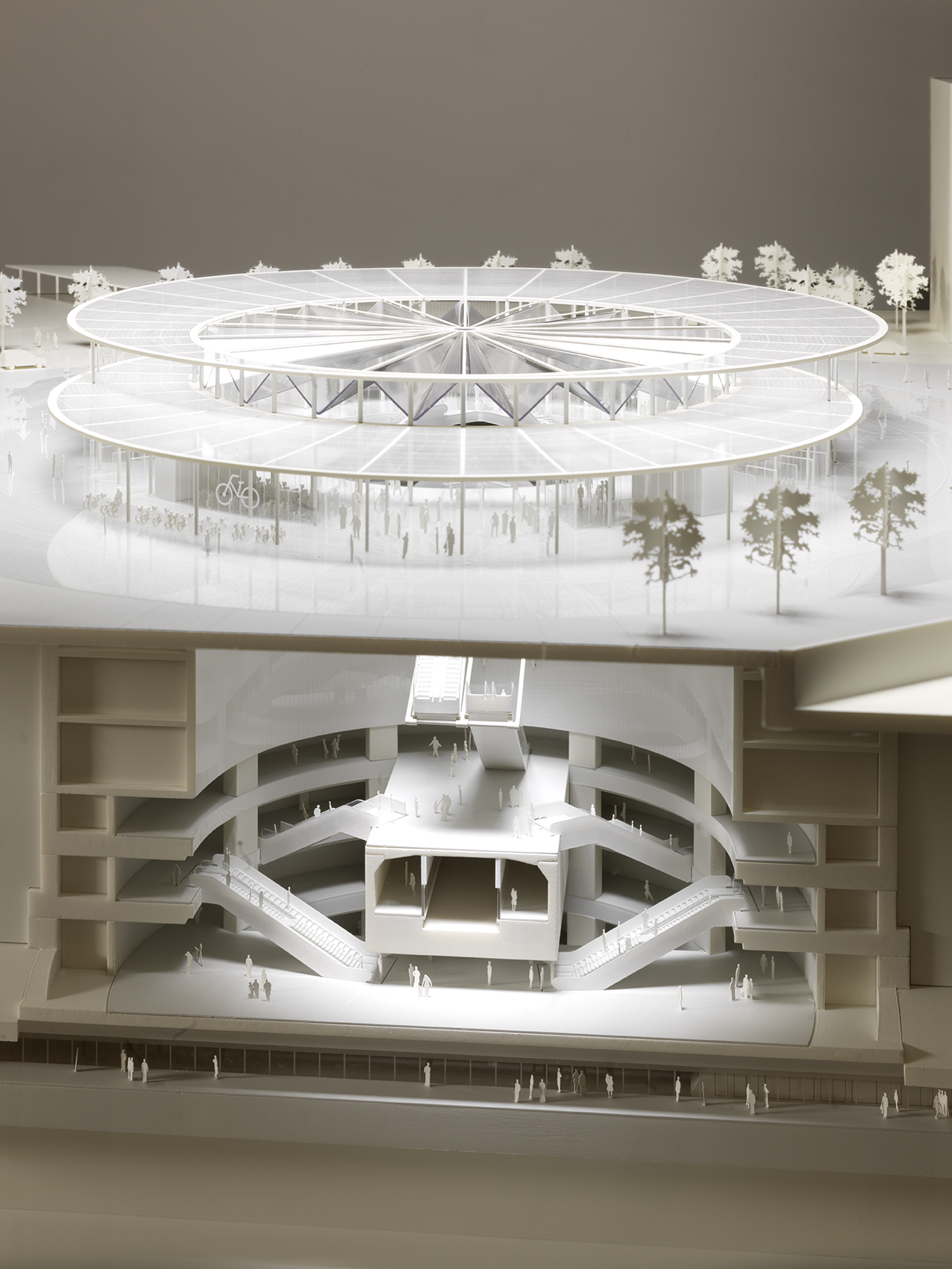

The development of Villejuif-Gustave Roussy also presented an interesting mission: Perrault aimed to remove the threshold between open public space and the enclosed space of the station. This was achieved by developing the station below ground, with only a pavilion with a transparent double roof observable on the surface.

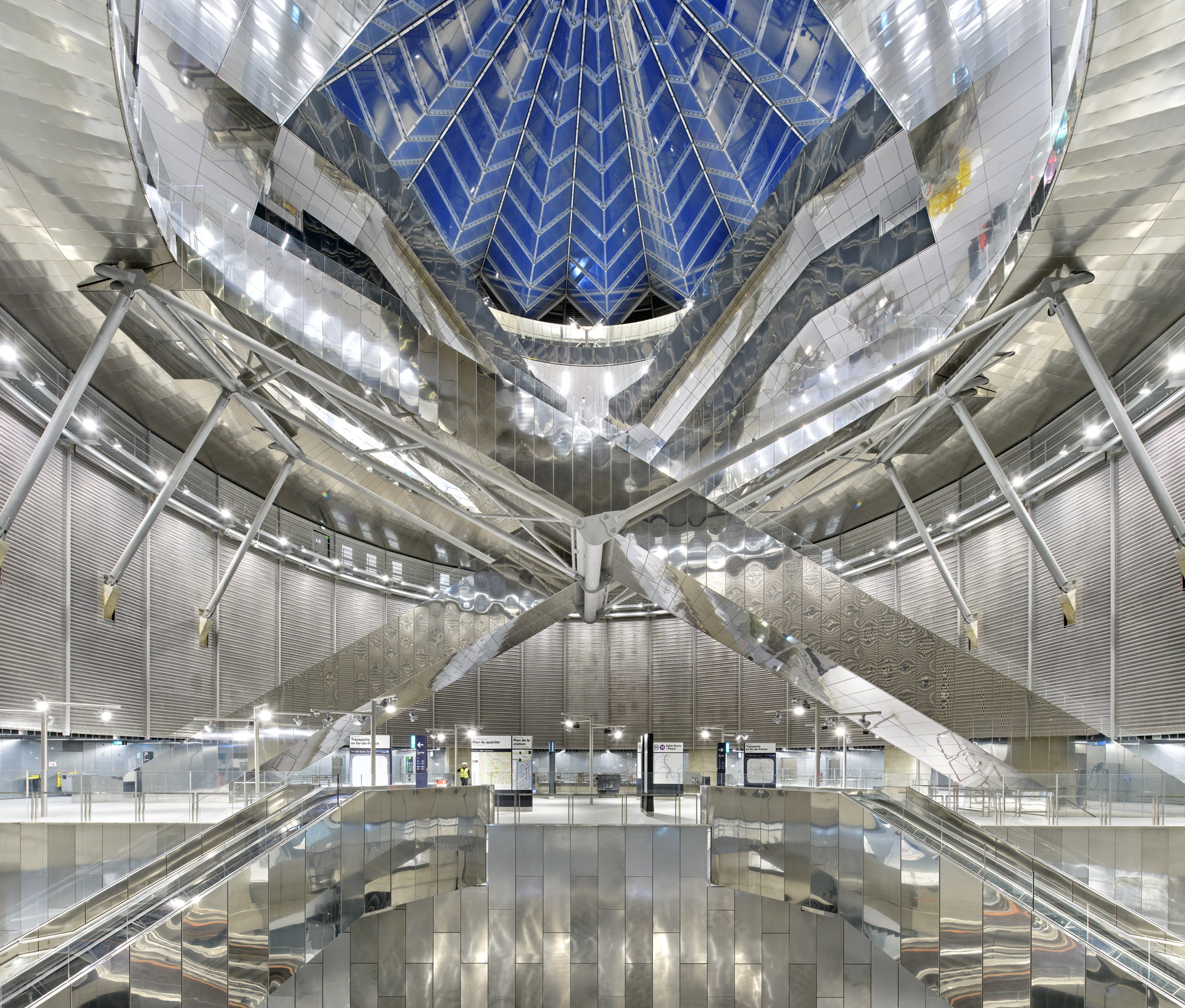

The body of the station is an open concrete cylinder with a diameter of 70m, described by the architect as an ‘inverted skyscraper’. Inside the cylinder is a series of galleries and balconies connected by footbridges and escalators.

One of the most important things about this structure is that it allows natural light to cascade into the realms below. (It also allows for natural ventilation and smoke extraction, as well as reduced heating and cooling requirements). Perrault wanted to disrupt the notion of the ‘underground’ – or ‘sous-terrestre’ – as uncomfortable, cold, damp and obscure. Villejuif-Gustave Roussy offers the opposite experience: light from the top of the cylinder even reaches the platforms, 50m below, and you can see the sky from the tracks.

The interior layouts, lighting and acoustics were also painstakingly thought-out to avoid Villejuif-Gustave Roussy becoming your archetypal ‘underground’ space. Materials range from concrete to glass and, most notably, stainless steel: this is deployed in a range of textures – smooth, mesh, perforated, mirror polish and satiny – to create different ambiances, whilst also continuing to make the most of the light.

‘Uncomfortable, cold, damp’ the station is not. Neither is it ‘obscure’: Villejuif-Gustave Roussy integrates public spaces, shops and services on the first two levels. Grand Paris Express developer, the Société des Grands Projets (SGP), also appointed €35 million for the inclusion of contemporary art in the 68 stations, with the aim of making the network into ‘a museum accessible to all’. At Villejuif-Gustave Roussy, Chilean artist Ivan Navarro created Cadran Solaire, an artwork depicting a starry sky made up of neon lights and mirrors.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A model of the Villejuif-Gustave Roussy station

The goal of the Grand Paris Express is not merely to improve access in Paris. It will also be instrumental in developing the areas that surround the stations. All of the stations in the network have been designed in collaboration with renowned architects, making some of them among the most aesthetically pleasing in the world, and ensuring that they leave a legacy for the area they serve. They will give ‘reality’ to the Greater Paris metropolis, ‘blurring of boundaries between the city-center and its suburbs’.

Villejuif-Gustave Roussy station, for instance, serves the ZAC Campus Grand Parc and the Institut Gustave-Roussy, the only oncology biocluster in France, and is slated to revamp the area with future office and housing buildings.

Despite its status as an architectural beacon, Villejuif-Gustave Roussy is designed in continuity with the surrounding public space: it has no walls or façade, instead sinking into the ground and disappearing from the horizon, effortlessly blending infrastructure and building design.

Anna Solomon is Wallpaper*’s Digital Staff Writer, working across all of Wallpaper.com’s core pillars, with special interests in interiors and fashion. Before joining the team in 2025, she was Senior Editor at Luxury London Magazine and Luxurylondon.co.uk, where she wrote about all things lifestyle and interviewed tastemakers such as Jimmy Choo, Michael Kors, Priya Ahluwalia, Zandra Rhodes and Ellen von Unwerth.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Stay in a Parisian apartment which artfully balances minimalism and warmth

Stay in a Parisian apartment which artfully balances minimalism and warmthTour this pied-a-terre in the 7th arrondissement, designed by Valeriane Lazard

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in France

Marta Pan and André Wogenscky's legacy is alive through their modernist home in FranceFondation Marta Pan – André Wogenscky: how a creative couple’s sculptural masterpiece in France keeps its authors’ legacy alive

By Adam Štěch

-

The museum of the future: how architects are redefining cultural landmarks

The museum of the future: how architects are redefining cultural landmarksWhat does the museum of the future look like? As art evolves, so do the spaces that house it – pushing architects to rethink form and function

By Katherine McGrath

-

Explore wood architecture, Paris' new timber tower and how to make sustainable construction look ‘iconic’

Explore wood architecture, Paris' new timber tower and how to make sustainable construction look ‘iconic’A new timber tower brings wood architecture into sharp focus in Paris and highlights ways to craft buildings that are both sustainable and look great: we spoke to project architects LAN, and explore the genre through further examples

By Amy Serafin

-

A transformed chalet by Studio Razavi redesigns an existing structure into a well-crafted Alpine retreat

A transformed chalet by Studio Razavi redesigns an existing structure into a well-crafted Alpine retreatThis overhauled chalet in the French Alps blends traditional forms with a highly bespoke interior

By Jonathan Bell

-

La Grande Motte: touring the 20th-century modernist dream of a French paradise resort

La Grande Motte: touring the 20th-century modernist dream of a French paradise resortLa Grande Motte and its utopian modernist dreams, as seen through the lens of photographers Laurent Kronental and Charly Broyez, who spectacularly captured the 20th-century resort community in the south of France

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain unveils plans for new Jean Nouvel building

Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain unveils plans for new Jean Nouvel buildingFondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain has plans for a new building in Paris, working with architect Jean Nouvel

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Discover Tempe à Pailla, a lesser-known Eileen Gray gem nestled in the French Riviera

Discover Tempe à Pailla, a lesser-known Eileen Gray gem nestled in the French RivieraTempe à Pailla is a modernist villa in the French Riviera brimming with history, originally designed by architect Eileen Gray and extended by late British painter Graham Sutherland

By Tianna Williams