Rem Koolhaas on OMA’s Rotterdam beginnings, Boompjes and Amex

We caught up with Rem Koolhaas to discuss OMA's beginnings, setting up shop in Rotterdam, and his new design for the Amex Centurion ‘Art Card', which was inspired by Boompjes, OMA's very first commission in the Dutch port city in the early 1980s

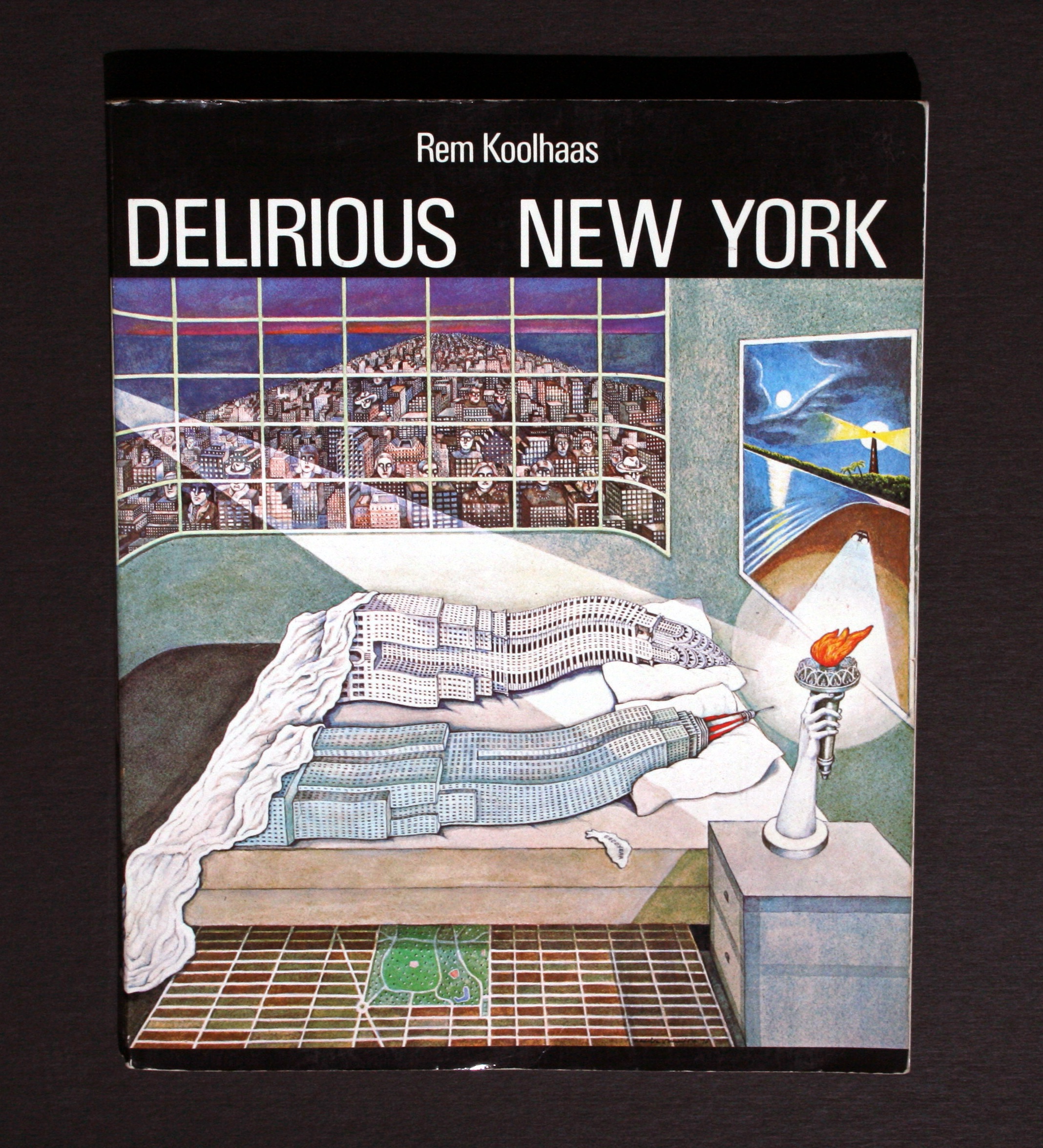

Rotterdam and OMA have long been intertwined. The Dutch port city has been home to the celebrated architecture practice for over four decades now, and it is also co-founder Rem Koolhaas’ birthplace. Still, the architect didn’t spend a lot of time there until the 1980s. Instead, he followed a more international trajectory in his early years. His childhood was mostly divided between Amsterdam and Jakarta, and after graduating from the Architectural Association in London, he moved to New York to attend Cornell. His book, Delirious New York, published in 1978 to much acclaim, was a kind of love letter to the great American city, exploring its development as well as notions of urbanity and congestion that came to define his career.

OMA was established in 1975 between New York and London (by Koolhaas together with Elia Zenghelis, Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesendorp) and by the time of the book’s publication, the architect was heading back to Europe. ‘I was in a strange position, as the book made me relatively well known, but I had never built anything,’ he admits. He decided to return to the Netherlands to pursue work; and if New York played a landmark role in making Koolhaas architecture’s favourite theorist, Rotterdam allowed him to build, to turn theory into practice.

Rem Koolhaas, captured by his daughter, artist and photographer Charlie Koolhaas, in Amsterdam in February 2021

Landing in Amsterdam in 1979, a meeting with a Rotterdam city councillor soon resulted in a ‘dream’ assignment – and one of the first big commission wins for OMA. ‘He was sitting in front of a map of Rotterdam and asked, “So, where do you want to build?” It was very generous. I saw a site on the river and the interesting thing about it was that it was very constrained on one side by water, on the other by a bridge, on a third side by a road and on the fourth by a building,’ says Koolhaas. He picked the site and started designing. The scheme was named Boompjes (‘little trees’ in Dutch) and mixed housing and workspace along the Maasboulevard. It marked the start of a long relationship between the port city and the architecture firm.

Rotterdam, devastated by bombing from both sides during the Second World War, presented a challenge and an opportunity for architects and planners in the second half of the 20th century – large parts of it had to be entirely rebuilt. This was also the reason Koolhaas chose it as his Dutch base in 1980, shortly after the Boompjes commission (two more schemes, the IJ-plein housing and a commissioned study for the possible renovation of the Koepel Panopticon Prison were also in the works in different parts of the country). ‘It made the city very fertile ground for architecture. I had more affinity and interest in Rotterdam. I started an office there almost on a hunch,’ he says. So, in the 1980s and early 1990s, the OMA headquarters was next door to the Boompjes’ plot and the water (a London office had opened in 1975, and Koolhaas and colleagues travelled back and forth as needed).

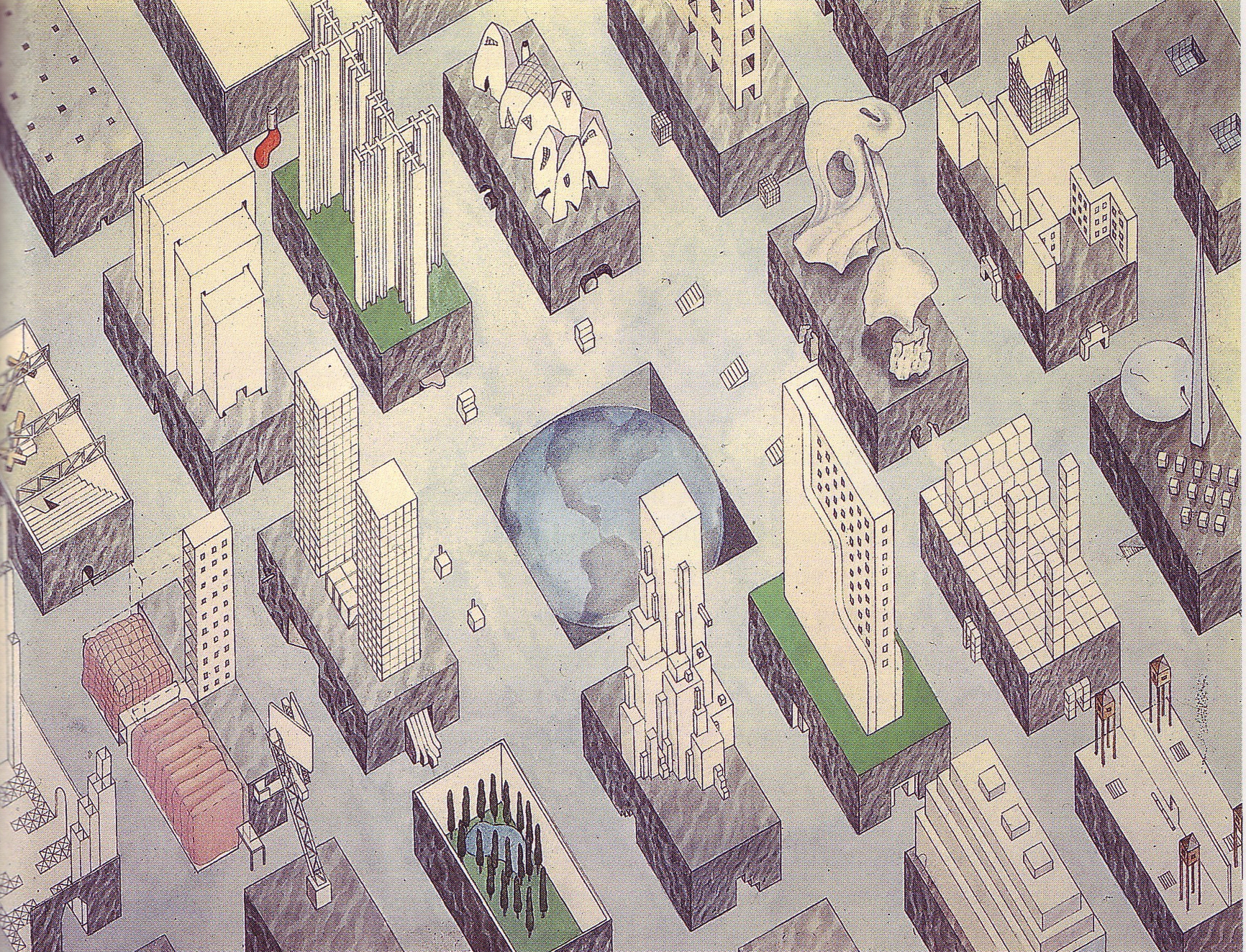

The cover of Delirious New York, published in 1978

Due to its geographical constraints, the Boompjes site could only be experienced in two ways: either passing by the road running parallel to the plot on ground level, or approaching it from across the River Maas via a bridge. These ‘unusually controlled’ views stimulated Koolhaas’ imagination and informed the design. This, combined with the fact that the city authorities allowed him great flexibility, meant the site was ripe for experimentation. ‘We made the design so that it was like an accordion. It could be spread wide or if you approached it from a single angle, you only saw a very narrow side,’ he says.

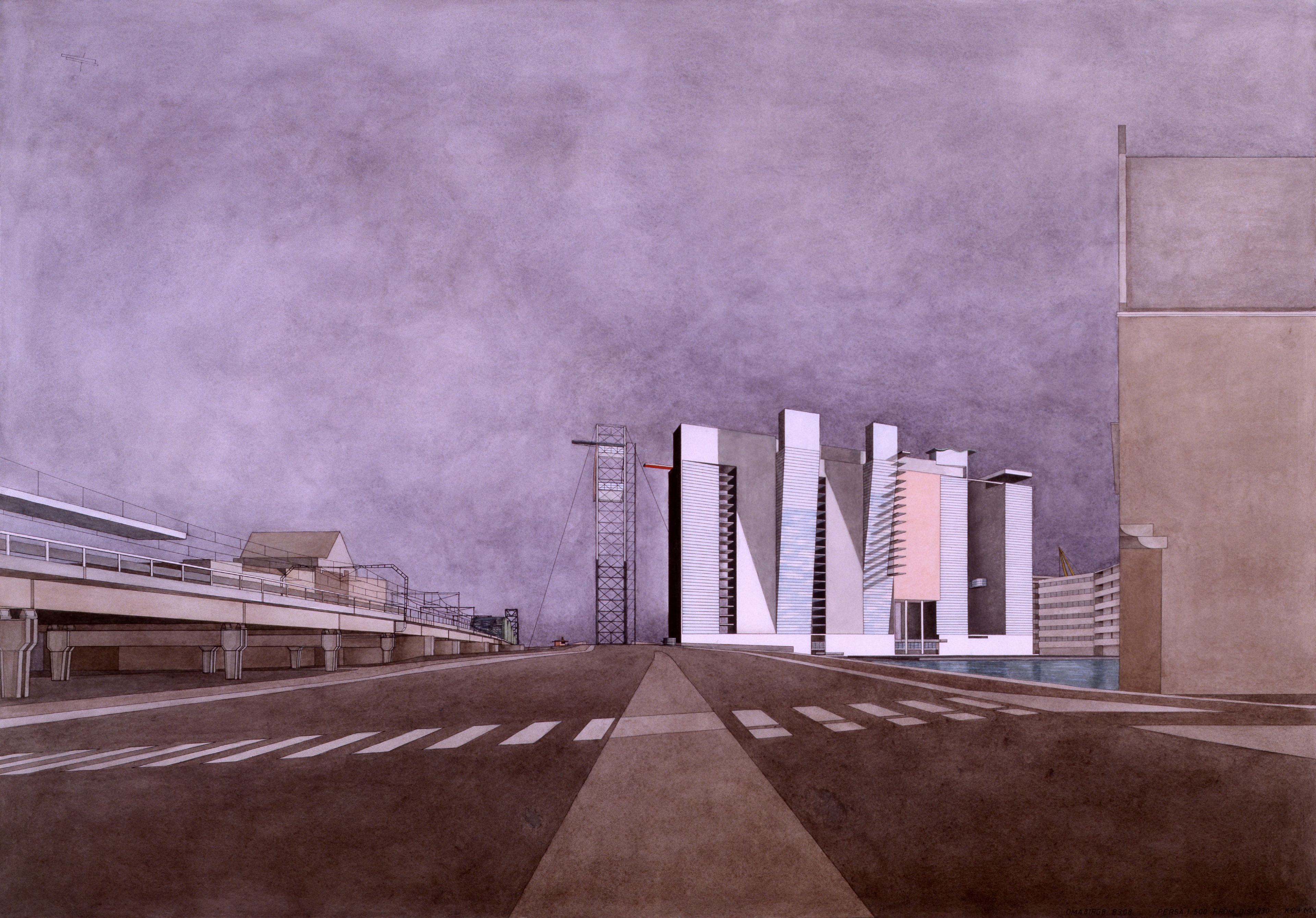

The formal response reflects Koolhaas’ architectural preoccupations at the time. The design incorporates a series of five tall, lean highrises set against a horizontal slab placed at the top. Some vertical elements are perpendicular to the slab, others sit at an angle, while one is just slightly apart. The formation became a kind of urban screen, filtering light and framing views from the river to the city and the other way round. ‘Of course, I had written a book about New York, but I was actually much more interested in another typology, the slab,’ the architect points out. ‘Towers are the expression of capitalism and slabs are the main expression of socialism. In the 1980s, it was very interesting to try and create a hybrid shape. Boompjes is a hybrid.’

A drawing for the Boompjes project, as seen from street level

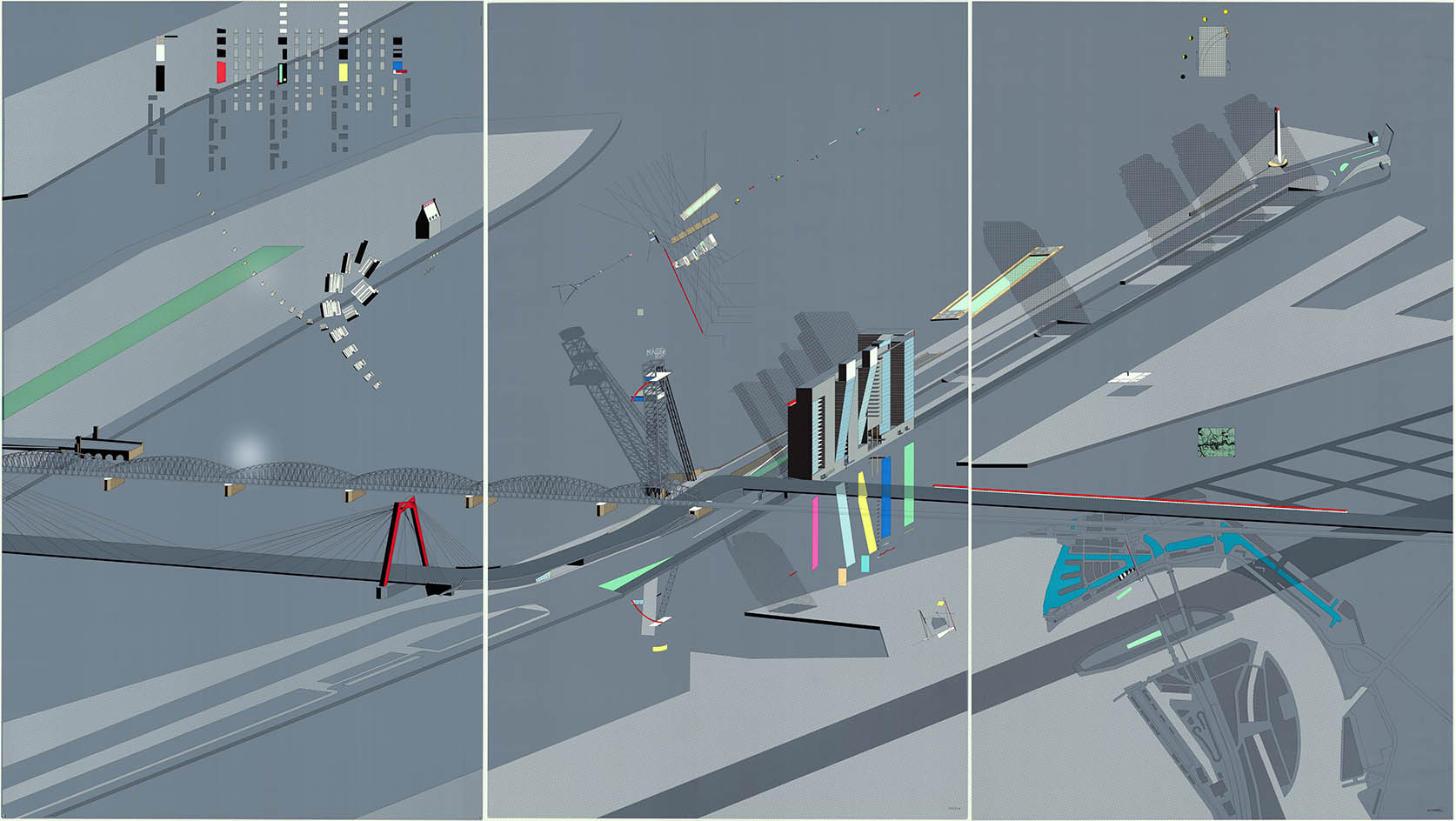

The main artwork for the design, produced in 1982, is a silk-screen rendering created by Koolhaas with Italian architect Stefano de Martino, and can still be found in the practice’s archives. It is a triptych – a colourful, geometric composition that brings to mind abstract or constructivist art, and the work of Piet Mondrian or László Moholy-Nagy. A print run of a couple of hundred editions was produced and now many of these sit in museum collections – at MoMA, the Centre Pompidou, CCA and The New Institute, for example. ‘We wanted to explain everything you need to say about this project in a single representation,’ says Koolhaas. The buildings’ colours nod to the passing ships’ bright hues; as port activity was ever-present in the office views, it provided constant inspiration.

Beyond formal considerations, Koolhaas’ vision for the long and narrow site explored new models for housing development and the future of living. ‘In the 1980s, housing in the Netherlands meant social housing,’ he says. ‘I had just come from America and I was interested in less defined spaces, open spaces. So the building had an industrial quality.’ The design, including a range of private apartments from studios to larger duplexes and loft-style spaces, with its river views, ‘was about flexibility, openness, an uncluttered space’. It also contained a gym and a library on site – a particularly forward-thinking move at a time when amenities in larger-scale residential schemes were anything but the norm.

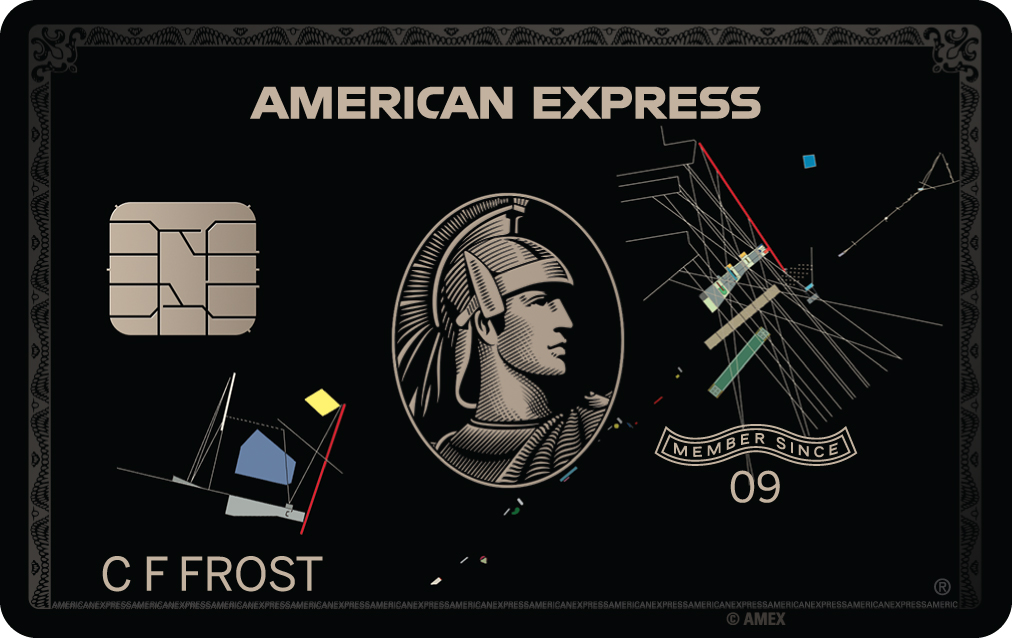

The Amex Centurion card, in collaboration with Rem Koolhaas, features artwork from an old OMA project, the Boompjes in Rotterdam

Boompjes was sadly never built (‘We presented it to the city a number of times; in the end they sold the site to a developer, but nothing came out of it,’ Koolhaas concludes) but its ideas were pioneering, and live on. In the late 1990s, OMA was commissioned to work on another site by the river in Rotterdam, which faced a similar situation – again, approached by a bridge and its perception controlled by limited viewpoints. That project, just across the water from the Boompjes site, eventually became De Rotterdam, a mixed-use, ‘vertical city’ completed in 2013 beside the city’s Wilhelmina Pier.

Now, Boompjes is about to get one more incarnation. In 2019, American Express approached OMA for an artistic collaboration with Rem Koolhaas on a new design for Amex’s exclusive Centurion Card. The practice had been working with the card’s signature Roman references, when the client came across the Boompjes project. It became a starting point for the new design, with Rem and his team adapting the triptych visual to the card’s specifications. The result launches from this month. Blending graphic design with thought-provoking architecture that was truly ahead of its time, the product is the smallest item ever designed by Koolhaas. ‘I see graphic design as a crucial domain to project ideas in,’ says Koolhaas, who regularly explores two-dimensional design through OMA’s research and design arm, AMO. ‘Architecture is also a domain to project ideas in. The similarity [between the disciplines] is about ideas, and these can take any form.’ §

The new Amex Centurion card was designed in collaboration with Rem Koolhaas

The Boompjes was designed in the early 1980s for a long and narrow riverside site in Rotterdam

One of OMA's 1980s drawings for the Boompjes

A photo collage by OMA showing the Boompjes within the city skyline

Photo collage by OMA showing the Boompjes approached by the water

Rem Koolhaas in the first OMA office in Rotterdam in the early 1980s, next to the Boompjes site and the water

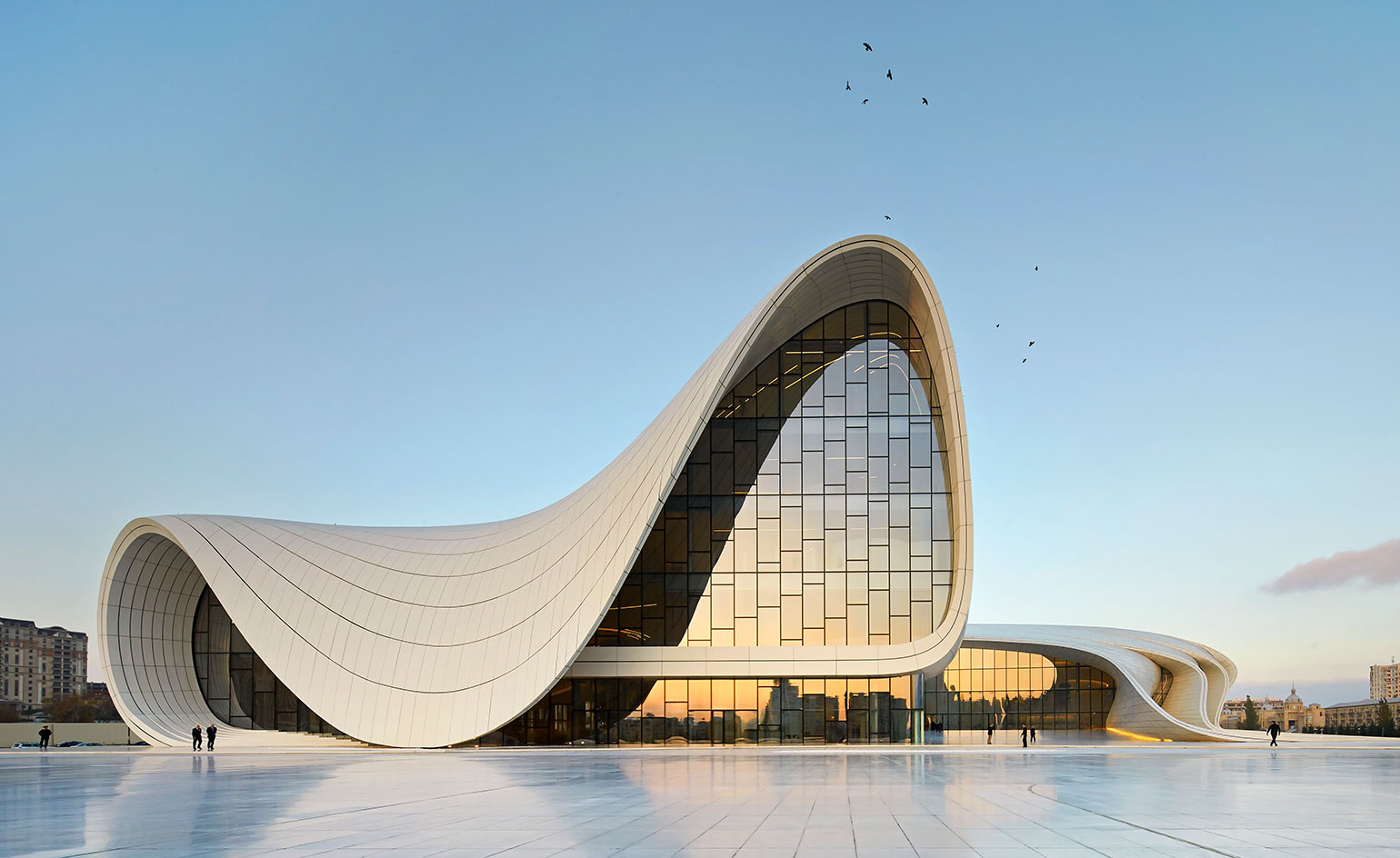

The north view of De Rotterdam by OMA, completed in 2013. Photography: Ossip van Duivenbode for OMA

'The City Of The Captive Globe' illustration by Rem Koolhaas and Zoe Zenghelis from the 1978 book Delirious New York

Mangalem 21, one of OMA's newest housing projects, headed by Reinier de Graaf and located in Tirana, Albania

INFORMATION

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Portlantis is a new Rotterdam visitor centre connecting guests with its rich maritime spirit

Portlantis is a new Rotterdam visitor centre connecting guests with its rich maritime spiritRotterdam visitor centre Portlantis is an immersive experience exploring the rich history of Europe’s largest port; we preview what the building has to offer and the story behind its playfully stacked design

By Tianna Williams

-

NYC's The New Museum announces an OMA-designed extension

NYC's The New Museum announces an OMA-designed extensionOMA partners including Rem Koolhas and Shohei Shigematsu are designing a new building for Manhattan's only dedicated contemporary art museum

By Anna Solomon

-

Rotterdam’s urban rethink makes it the city of 2025

Rotterdam’s urban rethink makes it the city of 2025We travel to Rotterdam, honoured in the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025, and look at the urban action the Dutch city is taking to future-proof its environment for people and nature

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: celebrating architectural projects that restore, rebalance and renew

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: celebrating architectural projects that restore, rebalance and renewAs we welcome 2025, the Wallpaper* Architecture Awards look back, and to the future, on how our attitudes change; and celebrate how nature, wellbeing and sustainability take centre stage

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Turin’s Museo Egizio gets an OMA makeover for its bicentenary

Turin’s Museo Egizio gets an OMA makeover for its bicentenaryThe Gallery of the Kings at Turin’s Museo Egizio has been inaugurated after being remodelled by OMA, in collaboration with Andrea Tabocchini Architecture

By Smilian Cibic

-

We stepped inside the Stedelijk Museum's newest addition in Amsterdam

We stepped inside the Stedelijk Museum's newest addition in AmsterdamAmsterdam's Stedelijk Museum has unveiled its latest addition, the brand-new Don Quixote Sculpture Hall by Paul Cournet of Rotterdam creative agency Cloud

By Yoko Choy

-

A peek inside the Nederlands Fotomuseum as it prepares for its 2025 opening

A peek inside the Nederlands Fotomuseum as it prepares for its 2025 openingThe home for the Nederlands Fotomuseum, set on the Rotterdam waterfront, is one step closer to its 2025 opening

By Ellie Stathaki

-

A guide to Zaha Hadid: from architecture to making 'a big hole' in Wallpaper*

A guide to Zaha Hadid: from architecture to making 'a big hole' in Wallpaper*Dame Zaha Hadid was a global, Pritzker Prize-winning architect and a force of nature; in this ultimate guide to her work, we celebrate her life, career and legacy

By Ellie Stathaki