Triple time: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners celebrates ten years together

The view gets in everywhere. Framed by the vibrant, putting-green flooring and arresting rows of red, orange and Yves Klein-blue seating, St Paul’s Cathedral stares straight back, approvingly, under typically leaden London skies. The still shockingly modern exoskeleton of the Lloyd’s building shimmers shyly next door behind grey Venetian blinds. We are on the 14th floor of 122 Leadenhall, commonly tagged the Cheesegrater and unarguably the most graceful of the brand name skyscrapers that now dominate the City of London.

These are the offices of, and powerful advertisement for, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP), the architects responsible for both this and its neighbour. The two buildings were rendered about 25 years apart, but with equal skill and beauty, in the heart of an annually more anodyne district. Nearly half of the buildings in this square mile of central London have been rebuilt in the last half- century. But, ever since the success of structures such as Lloyd’s first persuaded planners to raise permitted building heights, most of the surrounding offices are not graceful or delicate like Lloyd’s and Leadenhall, but hard, overbearing, inhuman even.

In the City and financial centres like it around the world, the same ideas seem to have migrated from architect to architect and from building to building, fluently, promiscuously. In all of this, RSHP has remained apart, doing its own thing and, astonishingly for so successful a practice, even flying a little under the radar – a 200-strong firm at a time when the biggest architectural practices employ 2,000.

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners’ limited-edition cover, picturing models of the practice’s latest projects, is available to subscribers

‘We spend most of our time trying to make big things look small,’ says Graham Stirk, one of the practice’s founding partners, wryly. ‘I think, in fact, it’s actually one of the biggest problems facing architects today, how you scale buildings up – which is what the market increasingly requires – without losing the human element. One thing I’d say about our firm is that we have one big advantage. We haven’t started out designing house extensions and worked our way up to bigger projects. I started here on big projects. My first job was on Lloyd’s 30 years ago. The fact is that the sensibility of doing bigger things is different. I’m not saying it’s harder, but it’s a completely different skill set that is required to give them a humanity of scale.’ It is now precisely a decade since the names of Ivan Harbour and Graham Stirk were added to that of Richard Rogers in the company title, and the likes of Andrew Morris and Lennart Grut were created senior partners and Ian Birtles, partner, but they had all been working together long before that.'

‘What changed when our names were added?’ muses Harbour. ‘The short answer is, not much. Except you start to feel personally responsible for the wellbeing of the office. Even today, if you ask what my hopes are for the next ten years, I’d say to still be here and still be solvent, and hopefully still have the chance to influence the conversation about urban density and vitality. But I’d settle for still being here, still clinging to the rock face.’ ‘The idea of creating the new partnership was really all about continuity,’ explains Rogers. ‘The only example I could think of where the names and the structure of the practice stay the same over time was Saarinen Swansen, and even then he was passing to his son. Mostly, for a practice like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, say, the founders go and the structure evolves into something else. Not good or bad, but different.

I didn’t want that. I wanted work at the same level of intensity and vision, so I asked the two most talented designers to join the masthead and added the directors.’ RSHP has always had a written constitution to help ensure this commitment to a similar vision is shared out equally. Famously, partner pay is capped at a fixed multiple of the lowest paid architect. And everywhere there is a feeling that intellectual interrogation is not some necessary evil, but the lifeblood of the place. Some architects find that their style slips into syntax as the years pass and the awards pile up. That their youthful flourishes assume the weight of an intractable world view, a weight for which they are not always prepared. These are not those sort of architects.

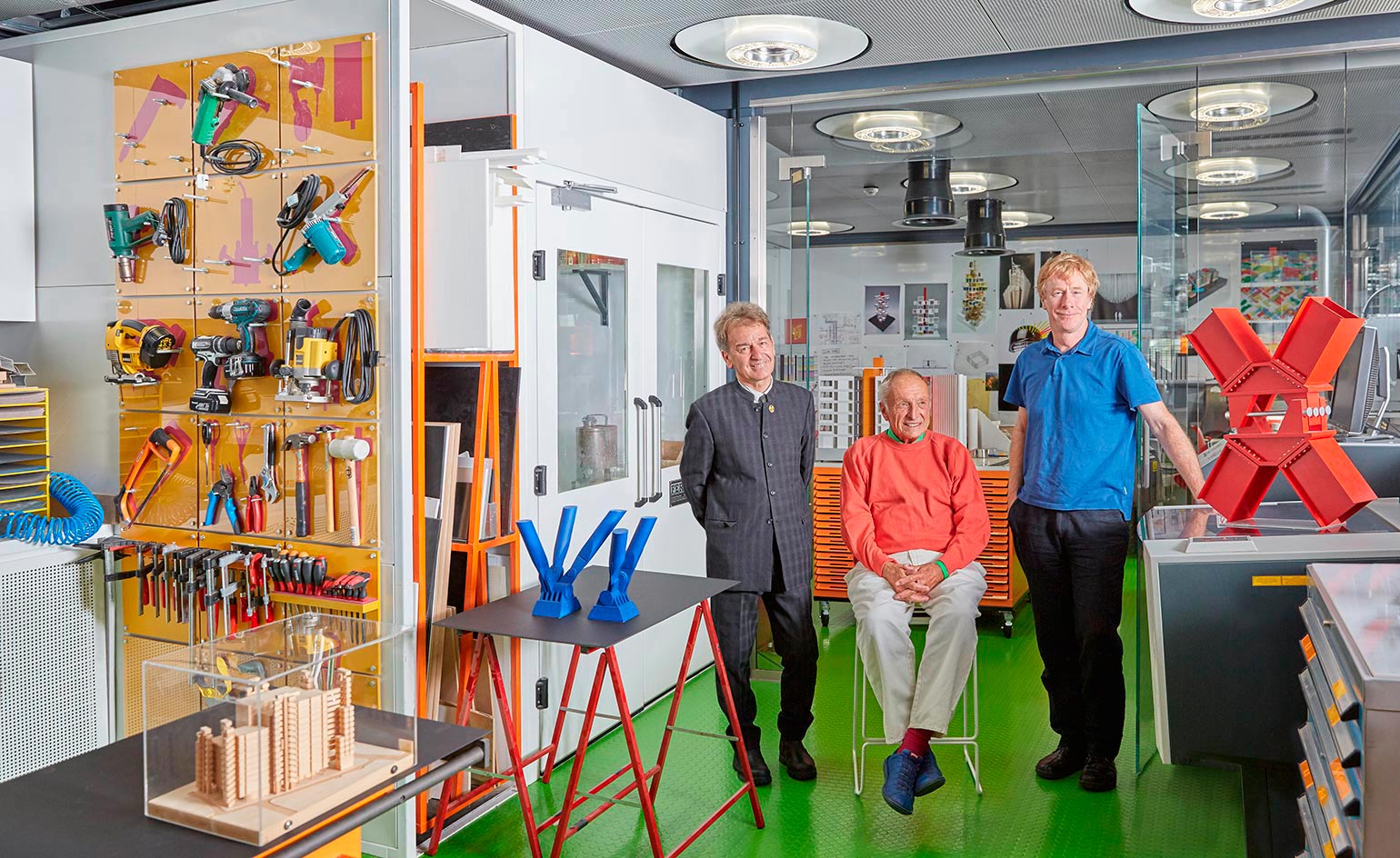

Models displayed at the RSHP offices in London

This flexibility can be seen in the fact that what was once a one-man practice that handled one project at a time, now has more than 40 projects on the go. These range from new airport terminals in Geneva, Taoyuan and Lyon, to a whisky distillery for The Macallan in Speyside in Scotland, and museum projects in Monaco and Lens. As expected there is much to admire. But there is so much more variety than one might imagine. Astonishingly, the British Museum extension, completed in 2014, was the practice’s first cultural assignment since the Pompidou Centre, completed in 1977. It will soon be joined by a new collections facility at the Louvre Lens.

Looking at the list of projects, the large scale and the impossibly large scale exist in a comfortable equilibrium. Ivan Harbour has been working on the largest: Sydney’s Barangaroo masterplan – think Canary Wharf, done by designers with soul – for as long as his name has been on the door. He headed up a team of 30 local architects, with six imported from the offices in London. It is, depending on how you measure these things, the largest infrastructure project in the world. The practice’s direct involvement is drawing to a close now, but there are still three buildings by Renzo Piano and one by Wilkinson Eyre to be delivered as part of Harbour’s plan. The project mirrors, in many ways, the resilience of the practice as a whole.

‘It turns out that 2007 wasn’t a great year to start a firm of architects specialising in large-scale infrastructure projects,’ laughs Stirk. ‘In fact, financial crises seem to time nicely with our ten years of existence.’ ‘Barangaroo only happened,’ continues Harbour, ‘because after six months Australia realised they didn’t have a recession. They thought they would get one like everyone else, but because of their banking regulations they didn’t. And then the Australian dollar shot up and not only was the project still on, it actually meant we could afford to do it.’

RSHP’s recent Place/Ladywell project is a partnership with Lewisham Council to create a temporary residential development and forms part of an ongoing research project on off-site manufactured housing

There is a tradition of architects adapting and improvising their way towards beauty in unpromising sites, as Herzog & de Meuron did with their railway signal box in Basel, or Calatrava with his textile warehouse in obscure Coesfeld, but this has become an RSHP trope. Neo Bankside, the upmarket, now five- tower residential scheme on London’s Southbank was envisaged as a single monolithic building by successive developers and planning chiefs, a dreary block on a dreary site. RSHP delivered air, space and transparency (a bit too much transparency for some residents facing Tate Modern’s new viewing platform).

Few buildings, though, travelled as far from their origins as the Geneva airport plan. ‘The airport is basically underground, underneath the runway,’ says Stirk, ‘and the plan called for what was essentially a 750m tunnel. You could have brightened it up a bit with a few light wells, but it would have been impossible to create an environment there to make travelling more pleasant.’ How the practice managed to do just that – creating a terminal with lakeside and mountain views – is a story that has been repeated in some form or other over the past decade.

In their best work, there is evidence of the relentless interrogation of solutions, tested in turn by the vagaries of budget or site or brief, or all three. The characteristic movement, as here at Leadenhall, is one towards purity and the beauty of simplicity.

‘Architects love to talk about simplicity and that is a virtue,’ agrees Stirk, ‘but simple and simplistic are two different things. Eighty six per cent of this building was made elsewhere and just assembled here. We had 250 people on site. When we did One Hyde Park in 2011, we had 2,000. Next door [the Lloyd’s building] had twice the budget and half the floor area, but that, if anything, is what we have learned in the last ten years. However you resolve architectural problems, you have to do more with less. And you absolutely can.’

As originally featured in the November 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*224) – out on 12 October

The gently undulating roof of the Macallan Distillery, which is to open next summer in Speyside, Scotland

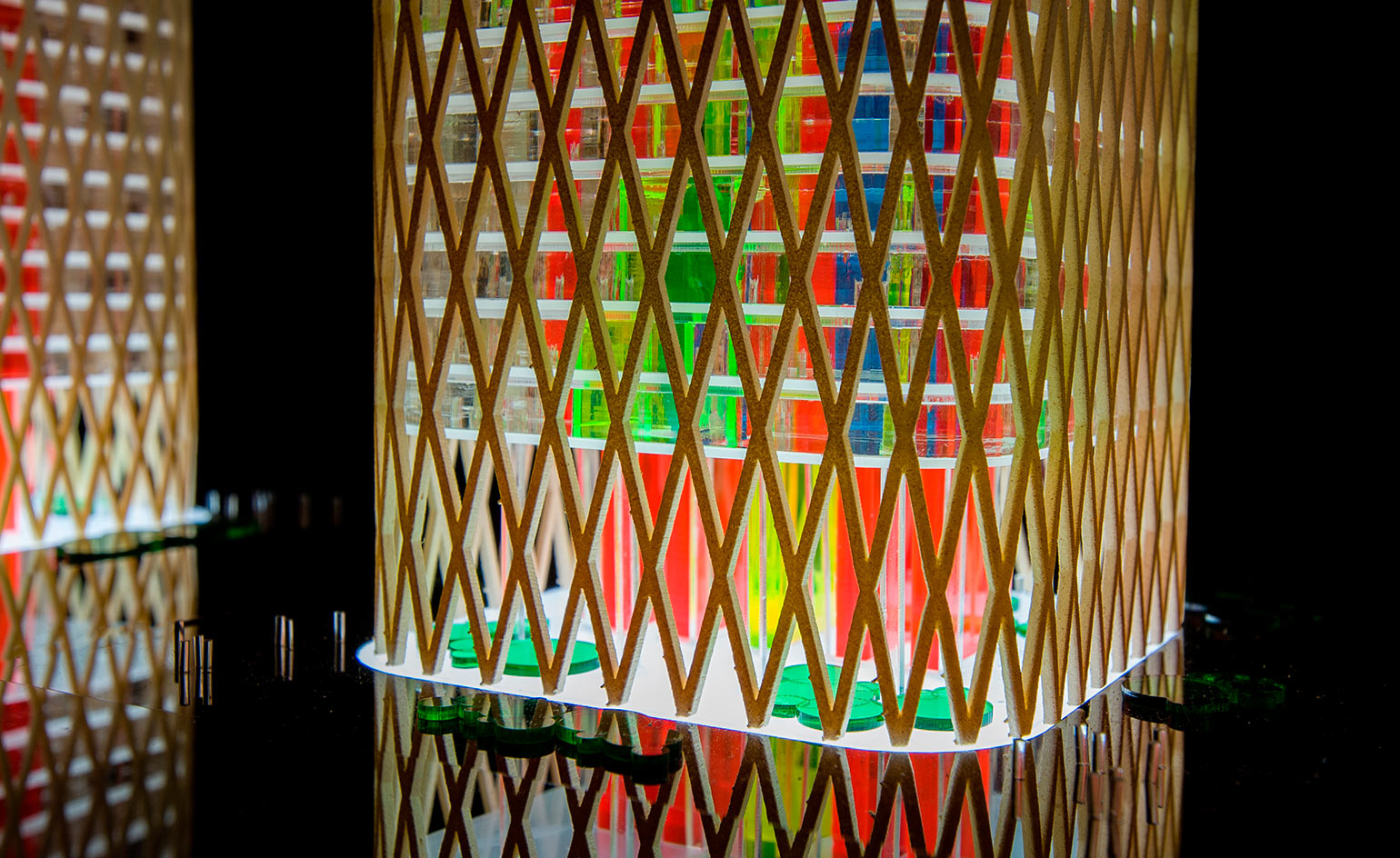

An exclusive shot of a development model designed in collaboration with Cambridge University and Atelier Two, currently in the works.

The practice’s current projects include a new terminal for Lyon airport, which will nearly double in size

Another current project, a cantilevered gallery space for French winery Château La Coste

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

A new London house delights in robust brutalist detailing and diffused light

A new London house delights in robust brutalist detailing and diffused lightLondon's House in a Walled Garden by Henley Halebrown was designed to dovetail in its historic context

By Jonathan Bell

-

A Sussex beach house boldly reimagines its seaside typology

A Sussex beach house boldly reimagines its seaside typologyA bold and uncompromising Sussex beach house reconfigures the vernacular to maximise coastal views but maintain privacy

By Jonathan Bell

-

This 19th-century Hampstead house has a raw concrete staircase at its heart

This 19th-century Hampstead house has a raw concrete staircase at its heartThis Hampstead house, designed by Pinzauer and titled Maresfield Gardens, is a London home blending new design and traditional details

By Tianna Williams

-

An octogenarian’s north London home is bold with utilitarian authenticity

An octogenarian’s north London home is bold with utilitarian authenticityWoodbury residence is a north London home by Of Architecture, inspired by 20th-century design and rooted in functionality

By Tianna Williams

-

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?DeafSpace learnings can help create profoundly sense-centric architecture; why shouldn't groundbreaking designs also be inclusive?

By Teshome Douglas-Campbell

-

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from Koto

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from KotoThe Niwa modular cabin series by UK-based Koto architects offers a range of elegant retreats, designed for easy installation and a variety of uses

By Jonathan Bell

-

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?Property developer Derwent London’s new lounges – created for tenants of its offices – work harder to promote community and connection for their users

By Emily Wright

-

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in Oxford

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in OxfordThe Gradel Quadrangles, designed by David Kohn Architects, brings a touch of playfulness to Oxford through a modern interpretation of historical architecture

By Shawn Adams