RSHP: a new name for a new era of collaborative design

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners rebrands as RSHP, heralding a new era of collaborative design for the architecture practice, following Richard Roger's passing in 2021

As of July 2022, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners will be simply known as RSHP. Wallpaper* covered the original transition from the Richard Rogers Partnership to Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners in 2007, which at the time felt like a pioneering move when few other major practices were bringing other partners into the limelight. Richard Rogers died in 2021 at the age of 88. In his later years, he had stepped back from day-to-day involvement in the firm he founded in 1977, alongside John Young, Marco Goldschmied, and Mike Davies, leaving Ivan Harbour and Graham Stirk to take a more prominent role. And now the firm has transformed again, becoming RSHP.

Exterior visualisation of the British Library extension from Midland Road.

Back in 2012, Rogers told The Guardian newspaper that the reason for the shift to Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners was because ‘we wanted to avoid the situation where the name of the practice is someone who died 100 years ago. Architecture is a living thing. If I want to leave something to the future, it has to be able to change – but retain something of the ethos that we built up over 50 years.’

Visualisation of the Montparnasse masterplan at night, Paris.

That ethos is still very much in place. Ivan Harbour joined the Richard Rogers Partnership in 1985, becoming a director in 1993. ‘Back in 2019 we spoke with Richard about changing the name,’ he recalls, ‘having previously agreed that we’d revisit the practice name after a decade of becoming Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.’

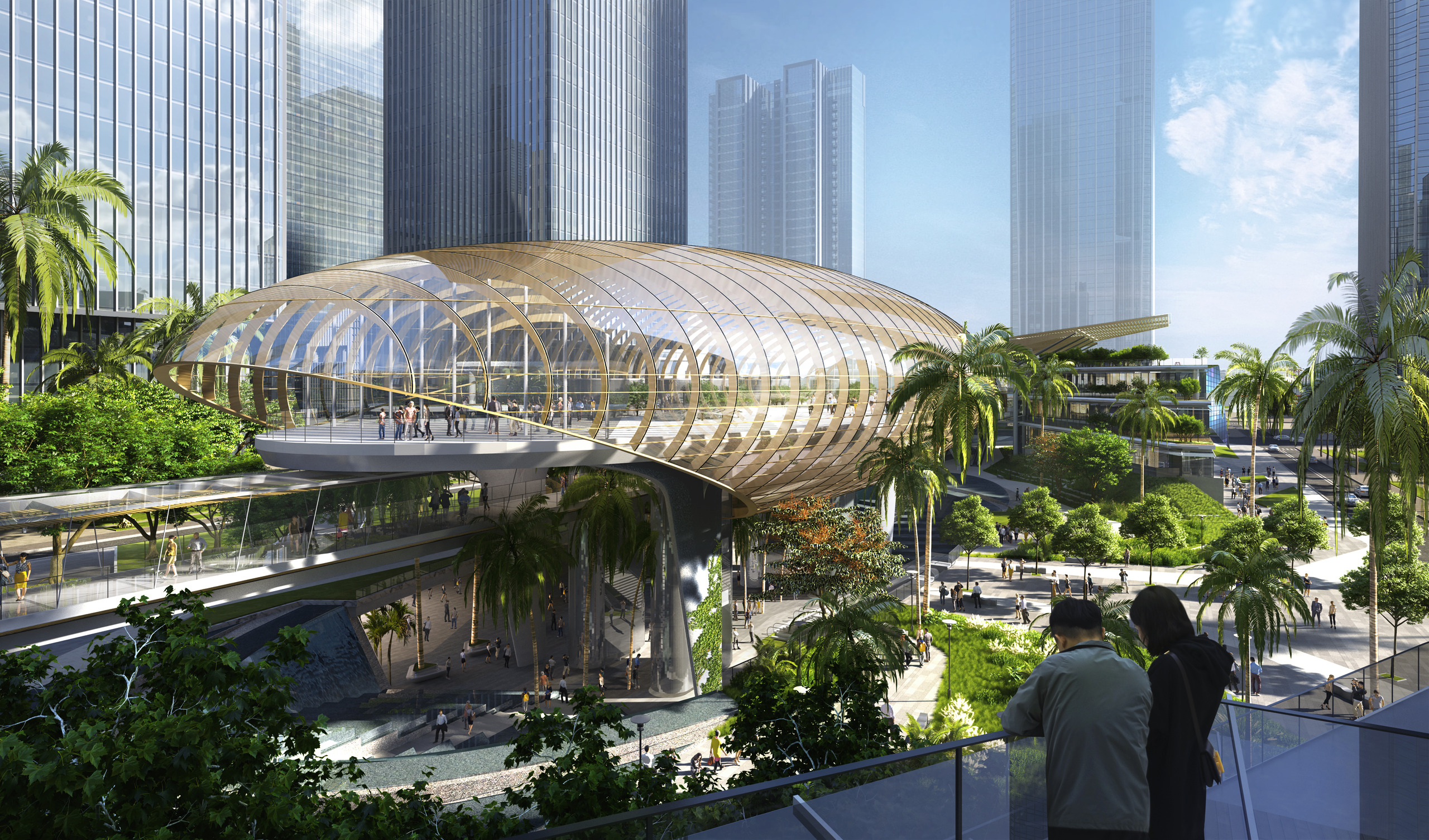

Render of the proposed Shenzhen Hong Kong Plaza.

Rogers’ death and the pandemic delayed the change, decided upon to address the office’s burgeoning reputation.

‘Although we were always an international practice, since we became Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, the work has changed to become truly global,’ Harbour continues, ‘We’re working in North and South America, Central America, Australia, China, Japan, etc. We took the view that although we don’t like the idea of being a brand, it was actually quite important to have a tag that represents what we are.’

Horse Soldier Farms, Kentucky, will incorporate a distillery, retail park, event centre, equestrian centre, and community rooms.

RSHP seemed like a natural progression. It still acknowledges Rogers’ formidable influence, as well as the continued guidance of Harbour and Stirk (another veteran, having joined in 1983), while bringing the stamp of acronymous authority that only initials can provide.

As Graham Stirk points out, ‘We now have 180 employees worldwide with a permanent presence in London, Paris, Melbourne, Sydney, Shanghai, Shenzhen and soon New York.’ On the boards are 44 projects, located in 15 countries across five continents. These include urban masterplans in Paris, the Metro system in Melbourne, an HQ tower in China, and the British Library Extension in London.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Render of Shimen First Road Tower, Nanjing, China.

‘Richard’s enduring legacy was the way the practice is constituted,’ says Harbour. ‘It may even still be unique, because the practice is owned by a charitable trust. That means we only physically own the furniture and computers and equipment, along with a little holiday house [north of] London, designed by Berthold Lubetkin next to Whipsnade Zoo.’

This property, one of two holiday bungalows designed by the émigré Russian architect in 1933, was originally for Lubetkin’s own use (the other was originally owned by pioneering eye surgeon Dame Ida Mann). Today, it is used as a retreat, available for staff to book. The charity also owns the practice’s comprehensive and valuable archive.

The model rack at the RSHP studio.

This structure has continued to shape the way the practice operates. ‘It was classic Richard in a way – “How can I think about practice in a way that has durability?” The idea of being equitable to everyone, looking after those who are less fortunate and being very family-based, these were ideas that were also super important,’ says Harbour.

‘Certainly one of the reasons I've been here for so long is because these ideals also appeal to me,’ he continues. ‘Architecture is a collaborative exercise. There are those who are out front and those who are in the back room, but they all have a role, they're all equally important. I enjoy that debate and I'm very practical – I built my own house, literally, over 12 years – and for me this place has always fitted. There have obviously been some amazing opportunities.’

Render of 14A Konstitucijos Avenue, a new seven-storey business centre in Vilnius, Lithuania.

The project that defined the early practice was Lloyd’s of London, which started in 1978 and was finally completed in 1986. It catapulted Rogers to stardom, helping shape a new, more media-friendly definition of this ancient profession. ‘Although the practice was very democratic, Richard took the role of standing out front, and being the public persona of the practice,’ says Harbour.

Throughout this period, the nature of authorship in architecture was hardly questioned. The starchitect era was defined by iconic buildings and iconic architects, but although Rogers stood shoulder to shoulder with his former partners Renzo Piano and Norman Foster, along with many other big names from that generation, there was always the sense that the Richard Rogers Partnership was more collegiate than corporate.

Staff look at a drawing on the RSHP studio floor.

‘There's been much written about Lloyd’s of London and the way that building came about. Lloyd’s saw this practice as a team that might help find the answer for them rather than give them the answer,’ Harbour says.

These days, such an approach is hardly unusual. Younger firms are more explicit about the collaborations that they do, whether it’s with clients or other professionals, and architecture is more about problem-solving than making bold statements.

Does the new name mean that RSHP will become more anonymous? ‘We wanted to put an emphasis on the group because I think it is more representative of how we are,’ says Harbour. ‘Of course, people love abbreviating, so in a sense it felt natural.’ When it comes to the work and the clients, the studio has always had what Harbour calls a ‘conversational approach’.

‘New clients approach us with preconceptions, and quite often the biggest preconception is that we’re used to working with large budgets, but on this project, you're not going to have so much. Well, believe me, everyone says that,’ Harbour says. ‘You also need a level of naivety to be creative. I've personally never thought of us as competing, but rather that we offer an alternative. However, I don’t know any other way. It’s an approach that I enjoy. In order to get through life, I think you have to enjoy it. We’re different, certainly.’

Render of MK Gateway, Milton Keynes, showing three new lightweight levels on the original Saxon Court.

Rogers was also a prominent campaigner for the built environment, both as an architect and in his political role as Lord Rogers of Riverside. ‘Richard was particularly unique as an architect because he was really a conductor. You can have the score and instruments, but you need a conductor to put the music together,’ says Harbour. ‘His interests took him to places that gave him more space to think laterally.

'Graham and I can originate – we can stare at a blank sheet of paper and talk about something that might emerge from it. That's quite hard work in itself. We did discuss with Richard whether we would try to replicate him and his approach. But ultimately we all need to be ourselves. When I first became a director, I asked him, “What are you expecting of me?” And he said, “Well, just we're expecting you to be what you are, nothing else.” I was clearly doing something right, so I just needed to keep going.’

Geneva Airport, Aile Est, completed in 2021.

RSHP will continue to quietly shift the paradigm. Aspects of the studio’s work – like prefabrication construction methods – continue to evolve. ‘We’ve been looking at modular construction for almost 20 years or more. I disagreed with Richard at one level, because I thought the success of our work on modular would be just to change construction – it didn’t really matter what it looked like. It was about minimising waste and increasing performance. Richard had a far more traditional modernist view – he wanted it to look modular.’

Render of Qianhai Financial Holdings Tower, Shenzhen, China.

Just as one of the earliest and most famous of all RSHP’s projects, the Lloyd’s building, was designed to accept change, so the practice itself is refusing to stand still. Harbour points out that the skyline is now almost completely enveloping this Grade I-listed modernist landmark, once the biggest building in London after the Natwest Tower.

New additions include the studio’s own 224m-high 122 Leadenhall Street – the so-called Cheesegrater – home to the RSHP studio since 2015, when it vacated its famous riverside studios in Hammersmith.

Aerial shot of Crofts Street, Cardiff, completed in 2022.

‘I think architecture has changed immeasurably over the last 30 years, but I think we can still surprise in good ways,’ Harbour says. ‘We've just completed some social housing in Cardiff, a carbon-positive scheme using modular construction. The [houses are] very modest.’ Although a great many of the buildings shaped by the studio have gone on to become instantly recognisable, enduring classics, Harbour doesn’t believe they’ve ever consciously followed fashion. ‘We're currently involved in five metro stations in Melbourne,’ he says. ‘One of the reasons we were brought in was that the local government was concerned about the “modishness” of the proposals. They told us this had to last a hundred years. I jokingly said that presumably, they asked us because as we’re never in fashion, we’re also never out of fashion.’

The rebranding is subtle and low-key, building on the identity created by Pentagram for the switch to Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, which resembled a typographic city skyline. ‘Personally, over the past 30 years, I’ve been consistently obsessed with making things work at a people scale,’ says Harbour. ‘So actually, the city skyline is less important to me, beautiful though the logo was. Instead, we have an identity mark – it’s less about names and more about the collective approach.’

RSHP Staff outside The Leadenhall Building, June.

INFORMATION

rsh-p.com

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

‘Independence, community, legacy’: inside a new book documenting the history of cult British streetwear label Aries

‘Independence, community, legacy’: inside a new book documenting the history of cult British streetwear label AriesRizzoli’s ‘Aries Arise Archive’ documents the last ten years of the ‘independent, rebellious’ London-based label. Founder Sofia Prantera tells Wallpaper* the story behind the project

By Jack Moss

-

Head out to new frontiers in the pocket-sized Project Safari off-road supercar

Head out to new frontiers in the pocket-sized Project Safari off-road supercarProject Safari is the first venture from Get Lost Automotive and represents a radical reworking of the original 1990s-era Lotus Elise

By Jonathan Bell

-

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean waste

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean wasteThe Canada-born artist draws on iridescence in nature to create a dual-toned textile made from ocean-bound plastic

By Ali Morris

-

An octogenarian’s north London home is bold with utilitarian authenticity

An octogenarian’s north London home is bold with utilitarian authenticityWoodbury residence is a north London home by Of Architecture, inspired by 20th-century design and rooted in functionality

By Tianna Williams

-

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?DeafSpace learnings can help create profoundly sense-centric architecture; why shouldn't groundbreaking designs also be inclusive?

By Teshome Douglas-Campbell

-

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from Koto

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from KotoThe Niwa modular cabin series by UK-based Koto architects offers a range of elegant retreats, designed for easy installation and a variety of uses

By Jonathan Bell

-

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?Property developer Derwent London’s new lounges – created for tenants of its offices – work harder to promote community and connection for their users

By Emily Wright

-

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in Oxford

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in OxfordThe Gradel Quadrangles, designed by David Kohn Architects, brings a touch of playfulness to Oxford through a modern interpretation of historical architecture

By Shawn Adams

-

A Norfolk bungalow has been transformed through a deft sculptural remodelling

A Norfolk bungalow has been transformed through a deft sculptural remodellingNorth Sea East Wood is the radical overhaul of a Norfolk bungalow, designed to open up the property to sea and garden views

By Jonathan Bell

-

A new concrete extension opens up this Stoke Newington house to its garden

A new concrete extension opens up this Stoke Newington house to its gardenArchitects Bindloss Dawes' concrete extension has brought a considered material palette to this elegant Victorian family house

By Jonathan Bell

-

A former garage is transformed into a compact but multifunctional space

A former garage is transformed into a compact but multifunctional spaceA multifunctional, compact house by Francesco Pierazzi is created through a unique spatial arrangement in the heart of the Surrey countryside

By Jonathan Bell