A South African collector’s art-crammed house in Bo-Kaap

The sloping suburbs hugging Cape Town’s historic centre are home to a mosaic of architectural styles, but rare is the building that defies common typologies. Cape Dutch, Victorian and art deco homes still predominate in tony neighbourhoods such as Oranjezicht and Tamboerskloof, while the luxe new villas in Higgovale are really updated interpretations of Palm Springs modernism. Even Bo-Kaap, where art collector Michael Fitzgerald recently built his extrovert cubist living space, is a museum to long-ago styles.

Once known as the Malay Quarter, in reference to Muslim inhabitants often descended from slaves, Bo-Kaap is best known for its spicy cuisine and brightly coloured Cape Dutch and Georgian terrace homes. ‘Being a Scotsman I always wanted to live in a castle,’ says Fitzgerald of the rectilinear structure he opted to build on a vacant plot on the ritzier edge of this historically working-class neighbourhood.

Fitzgerald’s study, which looks across the city to Table Mountain. On the left wall is a work by his favourite Cape Town artist, Jacob van Schalkwyk. On the bookshelf is a display of ‘Drunken Bricklayers’ glass vases by Geoffrey Baxter, as well as ten wooden ‘companion’ pieces sourced from Congo, Gabon and the Ivory Coast. His work desk is a 1961 piece by Nanna Ditzel.

Fitzgerald, who was born in Trinidad and followed in his father’s footsteps as an oilman before seguing into modelling, and later art dealing, drew inspiration from Tadao Ando’s early domestic architecture when composing his brief. His favourite Ando building is Azuma House (1976), a windowless house in Osaka. Assiduously quarantined from its neighbours by high concrete walls, the house has an exposed courtyard connecting two living areas. ‘You always risk getting cold or wet,’ says Fitzgerald. ‘It is absolutely fabulous.’

Cape Town’s verticality is an antidote to Osaka’s floodplain flatness. The views of the surrounding mountains from the upper two floors of Fitzgerald’s mixed-use building also clarify the home’s nickname, ‘Skypad’. Local firm Team Architects, whose studio is now located on the first and second floors, supervised the design. This is their third project for Fitzgerald.

Although a new build on a vacant plot, the Bo-Kaap property had its challenges. The site is bounded on three sides by existing heritage buildings. ‘One of the key things for us was to create simple proportions on the street façade,’ says Team Architects’ Philip Stiekema. The cuboid form with extruded elements rising over the congested Buitengracht Street may look at odds with the adjacent mix of shabby residences and industrial buildings, but its structure is rooted in the architectural lines of the neighbourhood’s older homes, says the architect.

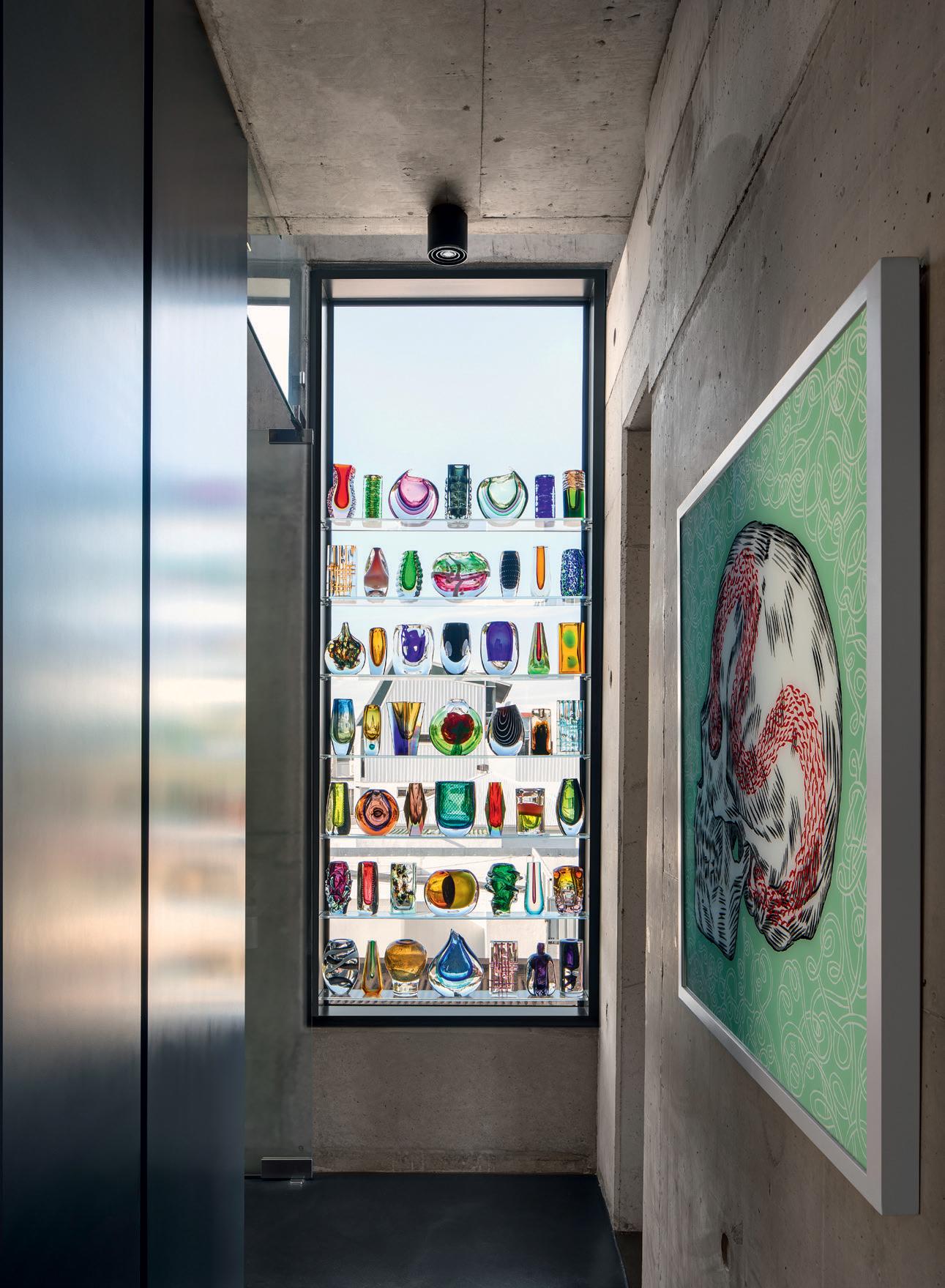

Midcentury glassware, and a work by Cape Town artist Conrad Botes, oil-based on reversed glass.

While Ando is Fitzgerald’s chief reference point, Stiekema also drew inspiration from the inventive materiality and sculptural qualities of Italian architect Carlo Scarpa’s work. ‘We tried to avoid the highway grey of aggregate concrete by pushing the colour mix,’ says Stiekema of the oxidised tone of the new building. ‘The driving force of the design, though, is its spatial, structural and formal complexity, and our attempt to synthesise all these things in a design characterised by its politeness.’ The last word is carefully chosen. In the past year, anti-gentrification protests have become more common in Bo-Kaap. After nearly three centuries, the neighbourhood’s traditional Muslim inhabitants are slowly being squeezed out as developers move in. Both Fitzgerald and Stiekema are aware of the current sensitivities.

Fitzgerald, a well-built man of 61 with a brush cut, leads me from his open-plan kitchen, past a Sudanese wood sculpture adorned with a beaded necklace from Nigeria, onto his sun-kissed terrace that in summer is shielded from the Cape’s vicious south-east winds. He points to an enormous development higher up the slope of Signal Hill. It is one of three large-scale developments, Stiekema later tells me when we speak, that have run roughshod over the community. ‘The upheaval is very complex and speaks to an unheard frustration,’ says Stiekema, who has been a Bo-Kaap resident since 1991. His team worked closely with Cape Town’s heritage department on the new building to avoid any community issues. The only pushback Fitzgerald has received since taking occupation was a snarky comment by a local youth.

The podium design of the Skypad incorporates off-street parking on the ground floor (a mandatory planning requirement) as well as a small gallery showcasing Fitzgerald’s holdings of traditional African art. ‘I can say I am an expert now, but I wasn’t when I started out two decades ago,’ Fitzgerald says of his career trading wood sculpture from equatorial Africa. ‘You’d buy things you thought were real only to find out they weren’t.’ Stock-in-trade African artefacts are stored in a modest storage area down a flight of stairs. ‘I don’t keep things piled up in cupboards. I’m not a hoarder,’ says Fitzgerald, whose tastes extend from traditional African art to work by contemporary South African artists, many associated with Cape Town’s Blank and Stevenson galleries. ‘I don’t ever deliberately buy something to sell. I will buy it if I like it, in the knowledge that one day it will move on. You get African art dealers who have thousands of pieces, but I am quite minimalist in my approach to it all.’

The gallery space with midcentury pieces, wooden statues from equatorial Africa and, on the wall, a work by local artist Jan-Henri Booyens.

Fitzgerald, who also consults, began collecting contemporary art while living in London in the 1980s. His go-to gallery was Joshua and Kitty Bowler’s Crucial Gallery, an experimental space on Portobello Road that championed raw work in metals and found materials. The sleeper-wood bench and table in the dining area is a reminder of this earlier phase in his collecting.

A notable feature of the voluminous living area is the grated steel walkway overhead, which connects the two en-suite bedrooms, with an additional section leading to a swimming pool. It too recalls a younger moment in Fitzgerald’s journey: ‘The oil rigs chased me all the way here,’ he laughs. ‘This is what I’m used to. They are uncomfortable to walk on, but tough.’

As originally featured in the November 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*236)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the The Curator website and the Team Architects website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Sean O’Toole is writer, editor and curator based in Cape Town. He has published two books, most recently a 2021 monograph on the expressionist painter Irma Stern, as well as edited three volumes of cultural essays, including 'The Journey: New Positions on African Photography', which received a New York Times critics’ pick for Best Art Books 2021. His exhibition projects include 'Photo book! Photo-book! Photobook!' at A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Remembering Alexandros Tombazis (1939-2024), and the Metabolist architecture of this 1970s eco-pioneer

Remembering Alexandros Tombazis (1939-2024), and the Metabolist architecture of this 1970s eco-pioneerBack in September 2010 (W*138), we explored the legacy and history of Greek architect Alexandros Tombazis, who this month celebrates his 80th birthday.

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Sun-drenched Los Angeles houses: modernism to minimalism

Sun-drenched Los Angeles houses: modernism to minimalismFrom modernist residences to riveting renovations and new-build contemporary homes, we tour some of the finest Los Angeles houses under the Californian sun

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Extraordinary escapes: where would you like to be?

Extraordinary escapes: where would you like to be?Peruse and lose yourself in these extraordinary escapes; there's nothing better to get the creative juices flowing than a healthy dose of daydreaming

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Year in review: top 10 houses of 2022, selected by Wallpaper* architecture editor Ellie Stathaki

Year in review: top 10 houses of 2022, selected by Wallpaper* architecture editor Ellie StathakiWallpaper’s Ellie Stathaki reveals her top 10 houses of 2022 – from modernist reinventions to urban extensions and idyllic retreats

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Mountain House is a contemporary South African hillside retreat

Mountain House is a contemporary South African hillside retreatArchitect Chris van Niekerk has designed a private mountain house that nestles into its site, providing space, views, and a sense of time and evolution

By Jonathan Bell

-

Roz Barr’s terrace house extension is a minimalist reimagining

Roz Barr’s terrace house extension is a minimalist reimaginingTerrace house extension by Roz Barr Architects transforms Victorian London home through pared-down elegance

By Nick Compton

-

Tree View House blends warm modernism and nature

Tree View House blends warm modernism and natureNorth London's Tree View House by Neil Dusheiko Architects draws on Delhi and California living

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Maison de Verre: a dramatic glass house in France by Studio Odile Decq

Maison de Verre: a dramatic glass house in France by Studio Odile DecqMaison de Verre in Carantec is a glass box with a difference, housing a calming interior with a science fiction edge

By Jonathan Bell