A new book unlocks the enigma of the Japanese garden

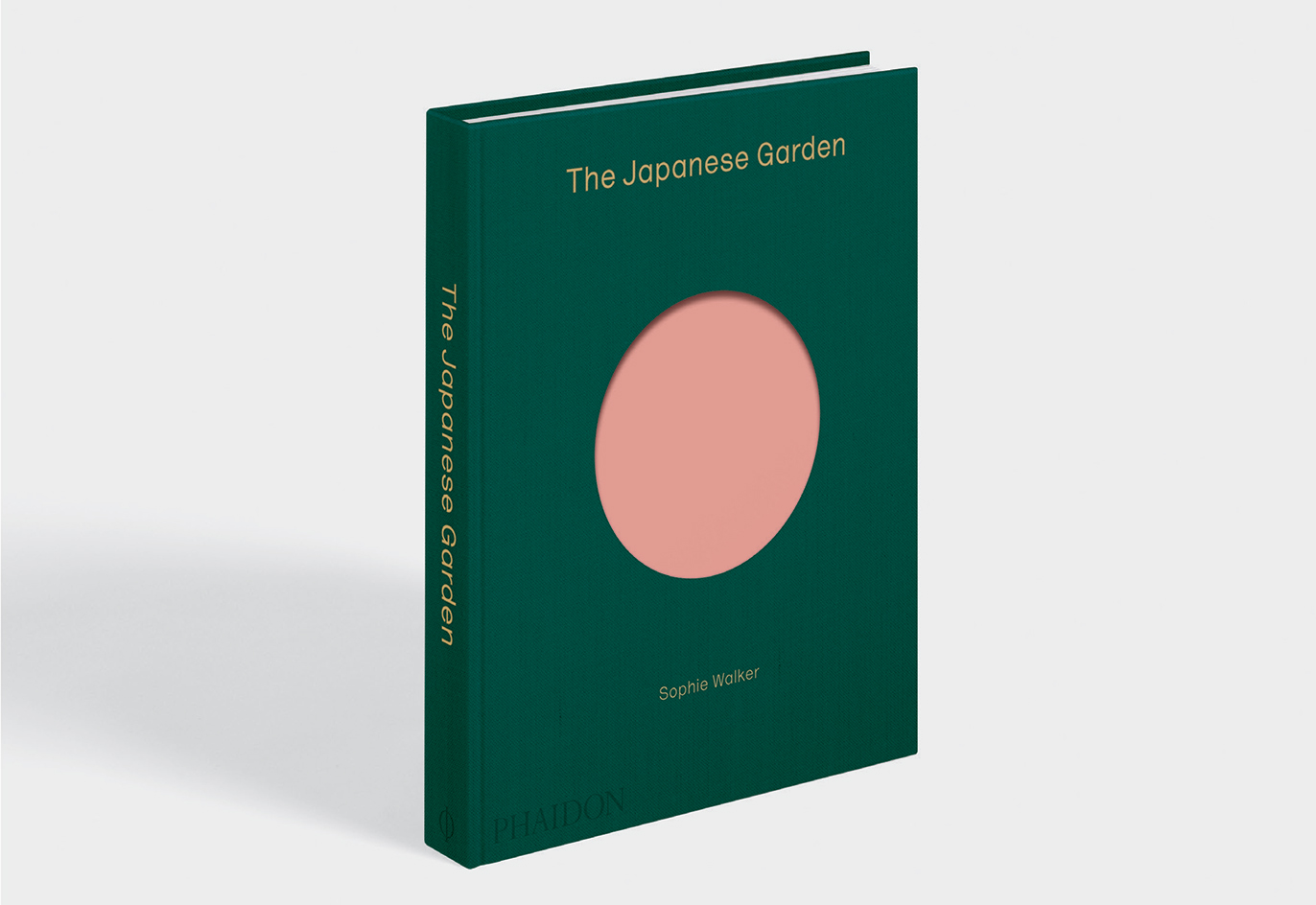

Insight into the enigmatic nature of the Japanese garden is revealed beneath a dark green fabric covered book written by garden designer Sophie Walker and published by Phaidon. ‘The Japanese Garden’ covers the history, design and concepts behind this unique Asian art form through a charmingly detailed narrative that varies in pace from thematic chapters, to intimate essays and photography inside which the reader can get lost.

Walker leads the way down a pathway of discovery rooted in Zen Buddhism, the arrival of Feng Shui from China, Japan’s distinct, diverse and unpredictable climate and landscape and the first written guide to the art of garden making, the sakuteiki or ‘The Reasons for Garden-making’, written in the 11th century.

Chapters explore and illustrate the distinct typologies of Japanese gardens – from Shinto shrines, Buddhist temple gardens, Imperial gardens, rock gardens, tea gardens, courtyard gardens and contemporary designs – always thematically interwoven with unifying concepts of self exploration, religion and Japanese culture.

The Shisen-dō, Sōtō Zen Buddhism, Kyoto, 1641, Edo Period, designed by Ishikawa Jōzan shows an example of how architecture was used to frame views of the garden.

Gardens grouped by typologies gradually educate the reader in the symbolic elements such as the path, the courtyard, still water, the bridge and the gateway. These each reveal precise meanings and are the tools that define the Japanese garden as a distinct art form.

Folded between chapters and photographs are essays by leading architects, artists and designers such as Tadao Ando, John Pawson and Lee Ufan that are short, personal treatises telling of intimate thoughts, experiences and ruminations on Japanese gardens.

Artist Lee Ufan writes of the gardens of Kyoto: ‘I am overcome by the sensation that time has stopped, that I have slipped inside another dimension.’ Kyoto’s historic gardens were designed as three dimensional manifestations of ancient East Asian paintings.

Techniques such as the shakkei or ‘borrowed scenery’ effect played with proportions to create the appearence of distant lakes and mountains, or plants were selected such as the niwaki-pruned pine trees in the Adachi Museum garden, to resemble wizened trunks of older trees, while the yellow Zoysia lawns of the Imperial Palace East Gardens in Tokyo appear like gold paint in the winters.

An example of the Japanese rock gardens closely connected to Zen Buddhism, the Kennin-ji established under the Rinzai Zen Buddhism school in Kyoto in 1202, Kamakura Period.

Another essay titled ‘Void, silence and transition’ by Anish Kapoor explored the Daisen-in garden of raked gravel in a courtyard that ‘offers no answers’ but ‘hovers in potential’ – theories that were directly connected to Zen Buddhist principles of remaining empty, yet therefore open to everything.

These Karesansui or rock gardens, were hugely influential in inspiring the minimalist post war conceptual art movement in Japan, Mono-ha, during the 1960s Japan, as well as internationally in the work of artists such as Richard Serra and Richard Long. The Zen rock garden of Ryoan-ji was the subject of a postcard from Walter Gropius to Le Corbusier in June 1954 as well as John Cage’s abstract composition for voice Ryoan-ji (1983-5).

From a barren rock garden full of potential, to the ‘unenterable’ courtyard garden designed to open a window to another world, and the stone pathway that carves out a psychological journey – Walker shows that the Japanese garden is as much a spiritual experience as it is a physical one.

The reflection of the garden and pavilion on still water is an important and carefully considered part of Japanese garden design. Pictured here, the Kinkaku-ji (Temple of the Golden Pavilion), a garden established within the tradition of Rinzai Zen Buddhism, in Kyoto in 1398, during the Muromachi Period. The pavilion was rebuilt in 1955, during the Shōwa Period. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2017

The Adachi Museum Garden in Yasugi designed by Zenkō Adachi in 1970 during the Shōwa Period, shows how scenery and plants were manipulated to look like a traditional East Asian painting.

Many Japanese gardens were designed not to be entered, but as a focal point for mediation. Here we see how water provides a boundary into the garden at the Chishaku-in in Kyoto, which dates back to 1593, Azuchi-Momoyama Period; and was restored by Unshō in 1764, Edo Period.

The bridge is a symbolic element of Japanese garden design referring to a transitional moment or a journey. Pictured here, cherry blossom above a wooden bridge at Kōraku-en, Okayama.

A courtyard garden at Kahitsukan Kyoto Museum of Contemporary Art, Kyoto, designed in 1981 by Kajikawa Yoshitomo with Akenuki Atsushi.

The Japanese Garden book published by Phaidon and written by Sophie Walker

The Shinto gateway is a feature of many Japanese gardens. Pictured here, the Ise Jingū (Ise Grand Shrine), dating back to the 3rd to 5th century, Kofun Period.

INFORMATION

‘The Japanese Garden’ is published by Phaidon

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

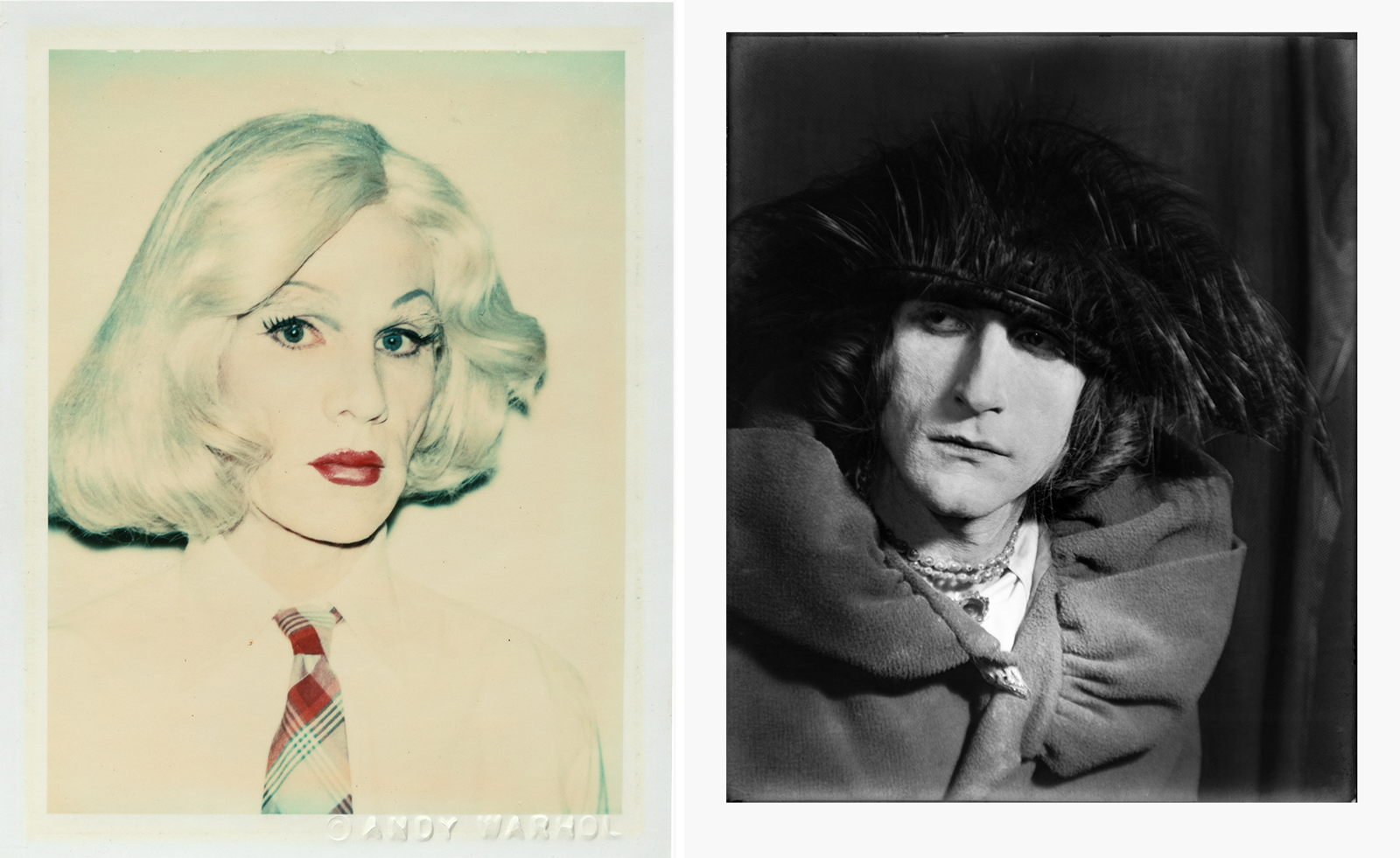

From Rembrandt to Warhol, a Paris exhibition asks: what do artists wear?

From Rembrandt to Warhol, a Paris exhibition asks: what do artists wear?‘The Art of Dressing – Dressing like an Artist’ at Musée du Louvre-Lens inspects the sartorial choices of artists

By Upasana Das

-

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architect

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architectPioneering Lisbeth Sachs is the Swiss architect behind the inspiration for creative collective Annexe’s reimagining of the Swiss pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

By Adam Štěch

-

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designs

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designsWatches from Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Rolex and more speak to universal design codes

By Hannah Silver

-

Giant rings! Timber futurism! It’s the Osaka Expo 2025

Giant rings! Timber futurism! It’s the Osaka Expo 2025The Osaka Expo 2025 opens its microcosm of experimental architecture, futuristic innovations and optimistic spirit; welcome to our pick of the global event’s design trends and highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

2025 Expo Osaka: Ireland is having a moment in Japan

2025 Expo Osaka: Ireland is having a moment in JapanAt 2025 Expo Osaka, a new sculpture for the Irish pavilion brings together two nations for a harmonious dialogue between place and time, material and form

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tour the brutalist Ginza Sony Park, Tokyo's newest urban hub

Tour the brutalist Ginza Sony Park, Tokyo's newest urban hubGinza Sony Park opens in all its brutalist glory, the tech giant’s new building that is designed to embrace the public, offering exhibitions and freely accessible space

By Jens H Jensen

-

A first look at Expo 2025 Osaka's experimental architecture

A first look at Expo 2025 Osaka's experimental architectureExpo 2025 Osaka prepares to throw open its doors in April; we preview the world festival, its developments and highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Ten contemporary homes that are pushing the boundaries of architecture

Ten contemporary homes that are pushing the boundaries of architectureA new book detailing 59 visually intriguing and technologically impressive contemporary houses shines a light on how architecture is evolving

By Anna Solomon

-

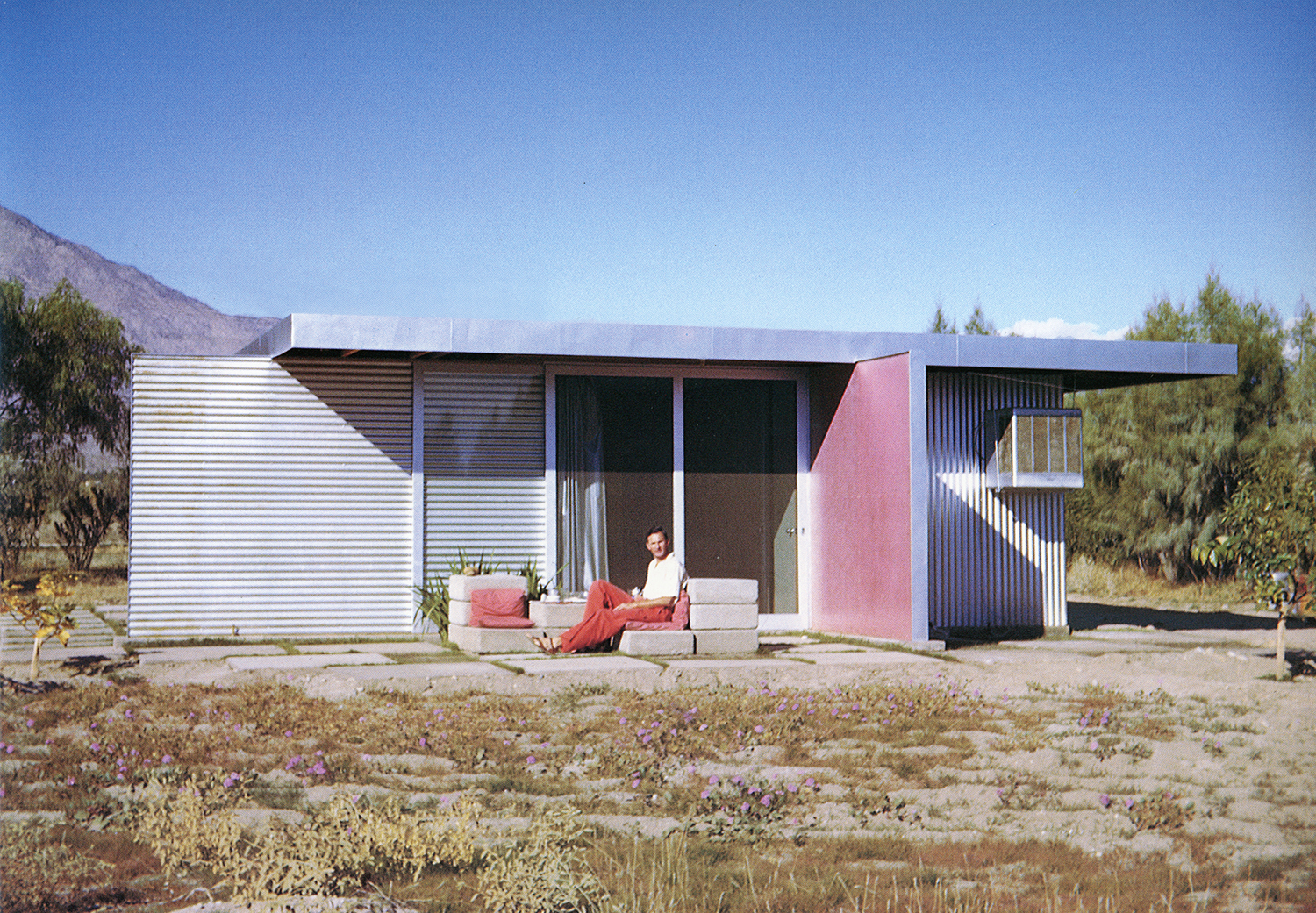

Take a deep dive into The Palm Springs School ahead of the region’s Modernism Week

Take a deep dive into The Palm Springs School ahead of the region’s Modernism WeekNew book ‘The Palm Springs School: Desert Modernism 1934-1975’ is the ultimate guide to exploring the midcentury gems of California, during Palm Springs Modernism Week 2025 and beyond

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Meet Minnette de Silva, the trailblazing Sri Lankan modernist architect

Meet Minnette de Silva, the trailblazing Sri Lankan modernist architectSri Lankan architect Minnette de Silva is celebrated in a new book by author Anooradha Iyer Siddiq, who looks into the modernist's work at the intersection of ecology, heritage and craftsmanship

By Léa Teuscher

-

And the RIBA Royal Gold Medal 2025 goes to... SANAA!

And the RIBA Royal Gold Medal 2025 goes to... SANAA!The RIBA Royal Gold Medal 2025 winner is announced – Japanese studio SANAA scoops the prestigious architecture industry accolade

By Ellie Stathaki