Toshiko Mori's well-connected community centre in rural Senegal has high ambitions

Toshiko Mori gives a talk introducing 16- to 25-year-olds to architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts in London tonight; to mark the occasion we revisit her 2015 community centre in rural Senegal

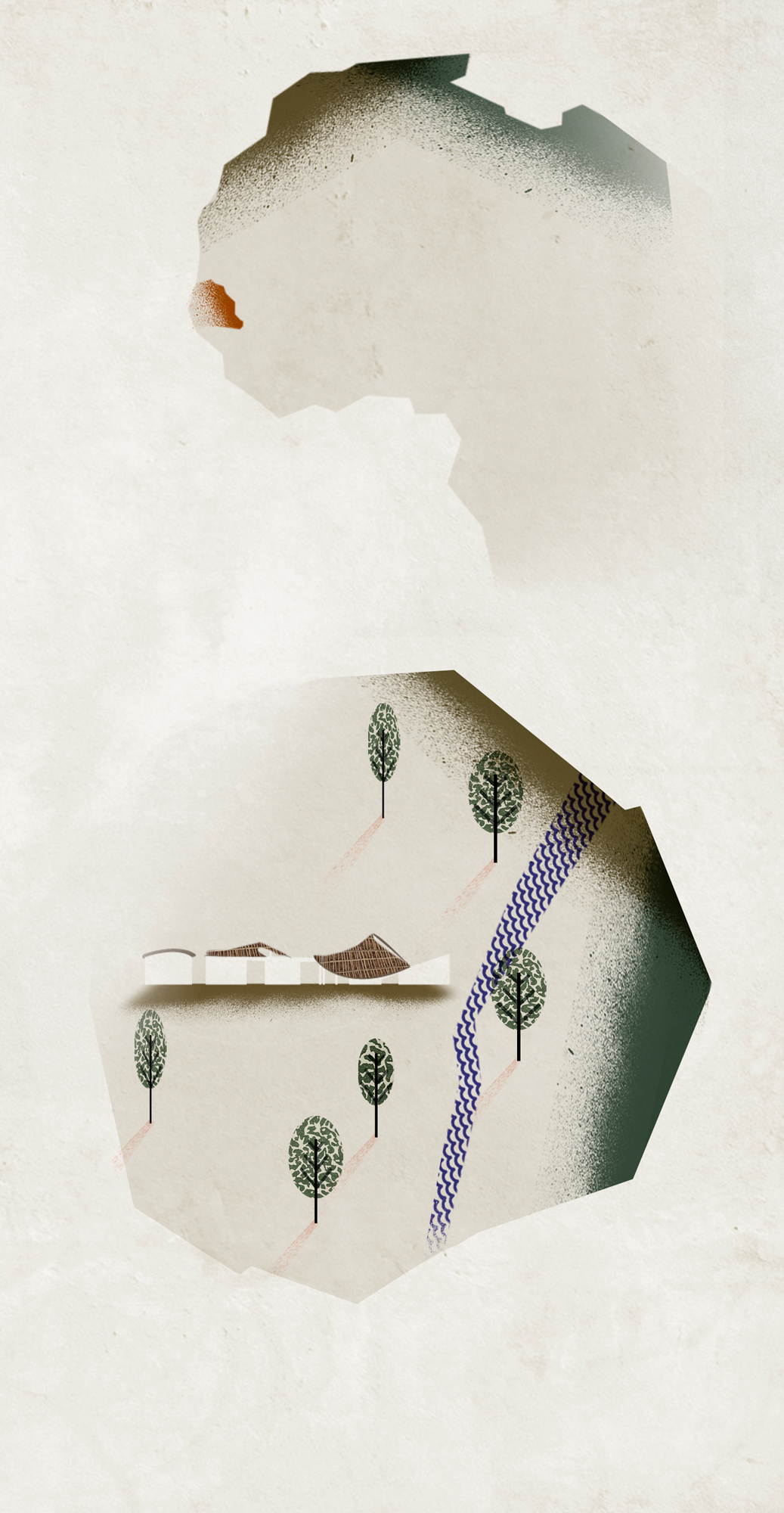

The connections that sparked the creation of this Toshiko Mori building are rich and varied. It is hard to imagine, for instance, what factors might unite the Japanese-American architect based in New York, Bauhaus émigrés Josef and Anni Albers, or at least their living representative, and a remote village in eastern Senegal. Yet this unlikely alliance, forged through a series of chance encounters, has resulted in an extraordinary building: a cultural centre for the Senegalese community of Sinthian, where a whole range of functions and activities are combined under one roof. Its name, appropriately, is Thread.

From Dakar, it’s a seven-hour drive to Sinthian, which sits close to the banks of the River Gambia. It’s a trip that the Mori, has undertaken a number of times. ‘You have to weave around cattle, sheep, donkeys and people on bicycles,’ says Mori. ‘When you arrive, you see that the region is one of flat grasslands and very beautiful. The locals are incredibly poor. They are impeccably dressed and wonderful people but they have to do their best with very limited resources.’

Tour Toshiko Mori's Senegal design

The Thread building, designed with Mori’s colleague Jordan MacTavish, is a pro bono project that provides two artists’ residences and a performance space with an open-air stage at its heart. Intended as a focal point for the community, it sits within an of-the-grid compound on the edge of the village that also includes a clinic powered by a solar array.

'It was important that Thread be close to the clinic, rather than removed from everyday life,’ says Mori. ‘The village sufers from water shortages, so we wanted to make sure the roof is also an instrument for rain collection. Collecting water from wells can keep girls out of school and means a lot of labour. This function means Thread becomes part of the infrastructure of the village.’

The link between Mori and Sinthian is the writer and cultural historian Nicholas Fox Weber, the executive director of the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation in Connecticut. The two first met when Mori was commissioned to design an exhibition devoted to Josef Albers. Fox Weber also happens to be the founder and president of a non-profit organisation, the American Friends of Le Korsa, which supports a wide range of projects in Senegal and pioneered the Thread building with assistance from the Albers Foundation.

‘Toshiko did a spectacular job with the Albers exhibition and was very receptive to the idea of what I was doing in Senegal,’ says Fox Weber, who first visited the country in 2003, following a chance encounter with a Paris-based medical professional who volunteered at clinics in West Africa.

The Thread building cost just €150,000 to build, which is very much in tune – as Fox Weber puts it – with the Albers’ maxim of ‘minimal means, maximum effect’. It was constructed by the community itself using local materials: baked mud bricks, bamboo supports and an undulating grass roof.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A programme of visiting artists is already underway, among them international writers, textile artists, dancers and video makers, who will run workshops with teachers, children and others in the local community with the aim of providing some of the pleasures that most of us take for granted.

The finished building references the local vernacular but has a distinctive, contemporary form all of its own. ‘It’s a real hybrid,’ says Mori – who is currently working on a new theatre in Manhattan and a pavilion for the Brooklyn Children’s Museum – ‘both of the existing typologies in the region, like the round thatched houses, and also of its different functions. With the open-roofed centre, it becomes a gathering space and a performance space, as well as a home.

‘It’s not that far from the border with Mali,’ she continues, ‘and in this area, there is a strong tradition of drumming called djembe. It’s a very active drumming culture, which is one of the reasons that the middle of the roof is open to the sky. People drum to communicate with the heavens. The sound of what they are doing here needs to ascend upwards.’

A version of this article was first published in the May 2015 issue of Wallpaper*

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Volvo’s quest for safety has resulted in this new, ultra-legible in-car typeface, Volvo Centum

Volvo’s quest for safety has resulted in this new, ultra-legible in-car typeface, Volvo CentumDalton Maag designs a new sans serif typeface for the Swedish carmaker, Volvo Centum, building on the brand’s strong safety ethos

-

We asked six creative leaders to tell us their design predictions for the year ahead

We asked six creative leaders to tell us their design predictions for the year aheadWhat will be the trends shaping the design world in 2026? Six creative leaders share their creative predictions for next year, alongside some wise advice: be present, connect, embrace AI

-

10 watch and jewellery moments that dazzled us in 2025

10 watch and jewellery moments that dazzled us in 2025From unexpected watch collaborations to eclectic materials and offbeat designs, here are the watch and jewellery moments we enjoyed this year

-

The 10 emerging West African architects changing the world

The 10 emerging West African architects changing the worldWe found the most exciting emerging West African architects and spatial designers; here are the top ten studios from the region revolutionising the spatial design field

-

ID+EA, Senegal: Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2023

ID+EA, Senegal: Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2023ID+EA from Senegal features in the Wallpaper* Architects’ Directory 2023, our round-up of exciting emerging architecture studios, with a commission for artist Kehinde Wiley

-

Senegal’s Mamy Tall on city planning, bioclimatic construction and heritage

Senegal’s Mamy Tall on city planning, bioclimatic construction and heritageMamy Tall from Senegal is part of our series of profiles of architects, spatial designers and builders shaping West Africa's architectural future

-

Explore Dakar-based Worofila’s hyper-local, sustainable architecture approach

Explore Dakar-based Worofila’s hyper-local, sustainable architecture approachStudio Worofila from Senegal is among our showcase of architects, spatial designers and builders shaping West Africa's architectural future