Elephant World wins Best Sanctuary: Wallpaper* Design Awards 2021

Including exhibition space set amid courtyards and pools, the Elephant World's architecture nods to both human and elephant needs; all, to a design by Boonserm Premthada's Bangkok Project Studio in Thailand

Spaceshift Studio - Photography

The work of Thai architect Boonserm Premthada walks the tightrope between a sharp, contemporary aesthetic and an intensely site-specific outlook rooted in tradition. One of his newest projects, a home for both people and elephants in the Surin province of lower north-eastern Thailand, demonstrates how.

Elephant World was created to support the Kui, the region’s ethnic people, and their beloved pachyderms. The Kui have been elephant keepers for centuries, considering the noble animals family members, and living with them side by side. However, in recent years, Thailand’s economic boom and urbanisation have threatened their way of life. Many have been displaced, their 400-year-old village falling into poverty and disrepair, endangering people and animals.

The corridors are elephantsized to cater to the animals, and the outdoor parts are interspersed with ponds that highlight the need for clean water for this endangered community’s survival.

The local government looked at ways to arrest that decline and create suitable and sustainable living conditions for elephants and humans. Premthada, and his architecture firm Bangkok Project Studio, won the commission and work began in 2015. ‘The architecture performs three functions,’ says the architect. ‘Preserving the culture; reviving the forest to ensure a supply of food and herbal medicines for elephants and providing a water source; and building a self-sufficient community economy through sustainable tourism that respects elephants and the Kui way of life.’

The design consists of three main parts: an observation tower, a museum, and what the architect calls the ‘cultural courtyard’, a 70m x 100m sloping roof, beneath and around which cultural events and religious ceremonies take place. (The wider complex also includes the historic Kui village, a field, temples and graveyards, but these were not designed by Premthada.)

The observation tower is located on the edge of the site, next to a forest. It was built from bricks made locally using earth from the construction of a new reservoir, dug to serve the 200 elephants in the compound (collectively, the animals require about 800,000 litres of water per month). Built for visitors to climb and take in the scenery, and observe the relationship between people and elephants below, the tower is also used as a platform from which to disperse seeds of the local Apitong trees, helping to renew the forest.

By contrast, the museum is a low building, composed of open-air corridors, enclosed galleries and spaces such as a library. Undulating roofs and wall edges create peaks and valleys that appear to spring out of the earth. The bricks used for the museum were created on site by local workers using loam found in the area. The presence of elephants is palpable throughout, and not only in the exhibits, which include stories that speak to the community’s heritage as well as the value of coexistence between people and nature. The corridors are elephantsized to cater to the animals, and the outdoor parts are interspersed with ponds that highlight the need for clean water for this endangered community’s survival.

‘To me, the museum is not just a single building,’ says Premthada. ‘It is all the buildings in the project, the village which has been there for 300 to 400 years, the trees and the existing landscape. And the stories in my museum are told by the local people.’

The hope, says Premthada, is for the forest to grow and take over much of the site, engulfing it in greenery, and making this a project that is at one with nature – a relationship as organic and effortless as the one between the Kui and the elephants. ‘Animals can transform a city, bring hope and pride to humans,’ he adds. ‘Humanity isn’t just about human relationships. We address our humanity through our relationships with other living creatures on the planet. The respect, or contempt, we show animals reflects our values as a human race.’

RELATED STORY

Elephant Museum

Elephant Museum

Brick Observation Tower

Elephant Museum

The Cultural Courtyard

The Cultural Courtyard water

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

-

Haute Couture Week A/W 2025: live updates from the Wallpaper* team

Haute Couture Week A/W 2025: live updates from the Wallpaper* teamFrom 7-9 July, Haute Couture Week A/W 2025 arrives in Paris. Follow along for a first look at the shows, presentations and other fashion happenings, as seen by the Wallpaper* editors

-

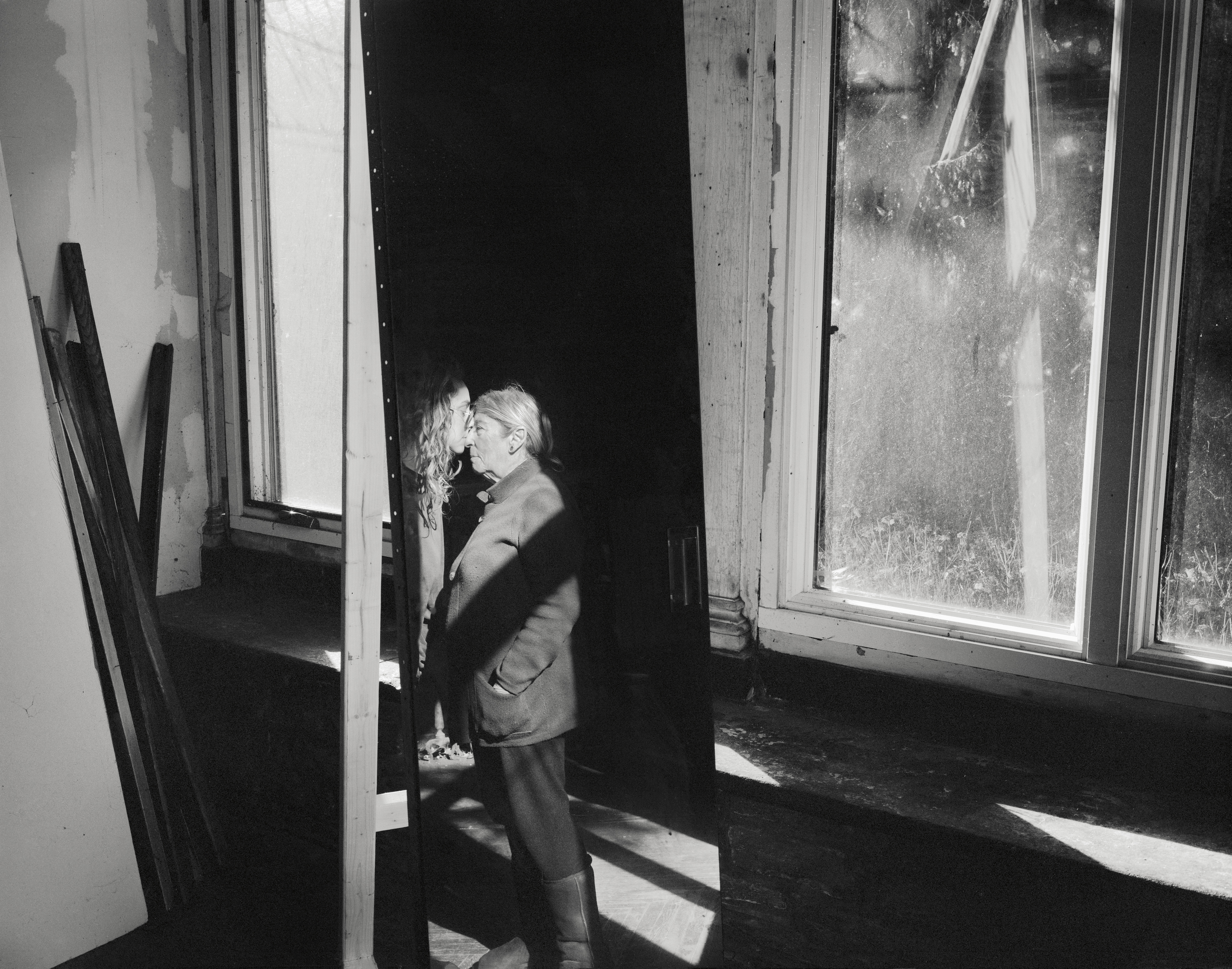

Boundaries between art and life dissolve in Katherine Hubbard's intimate documentation of her mother's illness

Boundaries between art and life dissolve in Katherine Hubbard's intimate documentation of her mother's illnessIn 'The Great Room', Katherine Hubbard merges caregiving for her mother with an unflinching documentary of the process

-

Michael Rider’s joyful Celine debut: ‘I’ve always loved the idea of clothing that lives on’

Michael Rider’s joyful Celine debut: ‘I’ve always loved the idea of clothing that lives on’Presented today in Celine’s Paris HQ, the designer’s astute debut balanced the house’s recent legacy with a fresh, contemporary vision which nodded to his American roots

-

Retreat to Aman Nai Lert Bangkok, a sleek city sanctuary

Retreat to Aman Nai Lert Bangkok, a sleek city sanctuaryAman returns to its Thai roots for its third civic outpost, weaving past and present to create an urban pleasure dome

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

-

How Four Seasons Hotels became The White Lotus’ unofficial star

How Four Seasons Hotels became The White Lotus’ unofficial starAs The White Lotus season three whisks us to Thailand, Marc Speichert, chief commercial officer of Four Seasons Hotels, discusses the luxury group’s perfect synergy with the hit HBO series – and where you can live the experience

-

Is this the future of fine dining? Culinary creative studio We Are Ona offers food for thought

Is this the future of fine dining? Culinary creative studio We Are Ona offers food for thoughtThe Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025 honour culinary creative studio We Are Ona, whose avant-garde pop-ups are turning the fine dining experience into an art form

-

A next-generation Milanese members’ club wins Wallpaper* Design Award 2025

A next-generation Milanese members’ club wins Wallpaper* Design Award 2025The Wilde wins our Best Social Hub award for its embodiment of the cosmopolitan Milanese spirit

-

London’s first all-suite hotel, The Emory, wins Wallpaper* Design Award 2025

London’s first all-suite hotel, The Emory, wins Wallpaper* Design Award 2025The Emory earns our Best Suites award for flawlessly embodying the creative aesthetic of a host of world-class designers

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: meet the travel winners transcending destinations

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: meet the travel winners transcending destinationsDiscover the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025 travel winners – the year’s places to stay, dine, drink and join – and watch our video to find out why they won

-

Tour an iconic 1970s Bangkok hotel reborn

Tour an iconic 1970s Bangkok hotel rebornA new generation of luxury awaits at the entirely rebuilt Dusit Thani Bangkok, with interiors by André Fu Studio