A tribute to French artist Michel Deverne

Artist Michel Deverne, who died last week aged 84, spent five decades building bridges between the worlds of architecture and art, transforming public spaces with his geometric sculptures and colourful collages. Wallpaper* spoke to him for our January 2011 issue (W*142). Here, we reprint the article in tribute to the

French master...

Long before La Défense became the largest business district in Europe, this area west of Paris was a wasteland where cows grazed, shanty towns proliferated and mushrooms grew in abandoned quarries. During the Occupation, Michel Deverne and his father used to take walks here, and the older man would proclaim, 'Nobody will ever develop this land. The ground under our feet is like a Gruyère cheese.' He couldn't imagine that 40 years later a jungle of skyscrapers would replace the shanty towns, and that his own son would construct two monumental art installations among them.

Michel Deverne believes that art should be an integral part of the city. He has spent his life beautifying buildings and public spaces with huge, abstract creations that seem to quiver with barely repressed energy. At La Défense, he turned banal ventilation shafts into works of wonder by coating the concrete cylinders with myriad coloured mosaic tiles. Cut in various sizes and in shades of blue, green, white and brown, some lie flat and others protrude, the graphic pattern swirling upwards and outwards.

Every year, millions of people pass by Deverne's sculptures in their daily lives. On a school lawn north of Paris, oversize aluminium spheres made of intersecting circles greet the students. At a service station near Dijon, motorists drive past a 9m obelisk of interlocking stainless-steel plates resembling a tower of origami birds. A twisting structure of concentric steel bands crouches in front of a post office in Avignon.

Deverne designed stained-glass windows for a chapel in Malta, and tapestries for the French Embassy in Islamabad. His structures and creations have sprung up in Cameroon, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Canada, Senegal, Belgium and the United States. Each one is conceived for its particular building or environment and meant to be exactly where it is. 'Deverne helped to revive the close relationship between artist and architect, as it existed during the Renaissance,' says the French art historian and critic Lydia Harambourg.

His artwork is replete with simple geometric shapes, often circles and helixes, that repeat and play off each other to create illusions of light and movement. There is a link to kinetic art, as well as the influences of Cézanne and Georges Braque in the fracturing of forms.

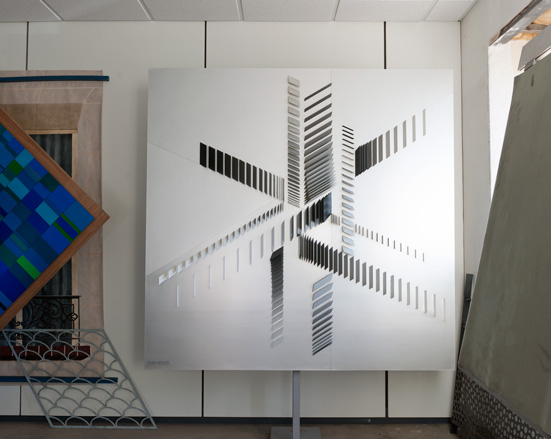

Harambourg compares his dynamic, rhythmic style to music. In one of Deverne's panels, lacquered white circles and semicircles in rows of diminishing size bring to mind the moon going through its phases. In another, stainless-steel blades ripple across and disappear into a metallic surface. These are sensual works that practically beg you to reach out and touch them, though you might just cut yourself doing so.

A tall, dignified man, who holds himself upright with the slightest Giacometti lean, Deverne was born in 1927, in the suburbs of Paris, in what he describes as a 'hideous' apartment building, since demolished. Like so many artists, he was a mediocre student whose one obvious skill was drawing. He still has a pencil sketch, made when he was 14, of his family's maid - an old woman with little round glasses, her mouth pursed in resignation.

He attended a series of art schools, learning to design and draw up plans at the École des Arts-Décoratifs, and perfecting his fine-art skills at the Beaux-Arts academy. After military service in Senegal, he returned to Paris to look for work. Somebody told him that Jean Carlu, the famous French poster designer, was artistic director at French publishing house Larousse, so he requested a meeting. 'He agreed to see me and asked if I wanted to be his collaborator,' he recalls. 'Trembling, I accepted.'

Deverne worked with Carlu for a few years before going it alone. One of his teachers had impressed upon his students that all true art was born of architecture. 'Back in the days of the Assyrians, Greeks and Romans, people didn't have little paintings they hung, carried around and sold. Buildings were the natural support for art,' he says. 'That excited us. When you are young you get carried away by the idea you are meant to create grand things.'

He could not have chosen a better time; France had been badly hit by war and everything was needed, from housing to hospitals. It was decreed that one per cent of any public construction budget be set aside for art, and Deverne took full advantage, he says, 'knocking on architects' doors'. He received his first major commission, two murals for the French finance ministry, in 1957, and then worked non-stop until the mid-1980s. In 1983, the Académie d'Architecture awarded him a silver medal for visual arts.

Deverne generally prefers the company of architects to artists. He would not have minded being one himself, though the requirements of the profession put him off. 'They are total athletes. You have to be a technician, an organiser, a leader, a team player. Then you have to sell yourself, smile at everyone, and say the opposite of what you believe.' Nonetheless, he thinks like an architect, and his work method is almost exactly the same. In his peak years, he directed a studio with up to ten assistants who built models and drafted plans. He subcontracted technical tasks such as steel-cutting or enamel work to specialised artisans. And he oversaw the installation of his pieces at building sites.

Some of Deverne's monumental creations have taken as long as buildings to go up. His most important commission was Les Miroirs at La Défense, which he claims is the largest mosaic structure in the world, at some 2,500 sq m. His studio worked for more than two and a half years to realise it, from the models through to the technical drawings and finally the construction itself, upon which ten mosaicists laboured for a year.

The art world is now rediscovering Deverne. In the winter of 2006, the Musée Carnavalet, devoted to the history of Paris, hosted an exhibition of his sculptures, reliefs and models, called 'Tensions et Vibrations dans la Ville' - Deverne's first solo show in a museum. Bruno Quantin, a spokesman for the museum, says, 'He always created work of the highest quality, and with such great precision that it will remain a reference for the era.'

More recently, a private gallery - the RCM Galerie, steps from the Musée d'Orsay - started representing Deverne for the first time. It is run by the American dealer Robert Murphy, who first became aware of Deverne's work at the Musée Carnavalet, then saw a monumental brass door of his at an exhibition outside Paris. 'I thought it was amazing,' says Murphy. 'So I tracked him down.' He has since sold several Deverne artworks from the 1960s and 1970s, and [from December 2010 to January 2011, he hosted] a solo show of the artist's post-war sculptures and reliefs.

Sadly much of Deverne's work his been destroyed over the years. Many of his built works have disappeared, victims of new construction or changing fashions. And many of his smaller sculptures and reliefs - displayed or stored in his own home in Montmorency, outside Paris (featured in W*142) - were destroyed in the fire that also tragically claimed his life.

Above all, Deverne was a man who lived for his art. Says Murphy (also a personal friend of the artist): 'He rose at dawn and worked until 8pm, soon after which he would retire for the evening. There was no TV in his house - too distracting. No portable phone; no email. Creative work was all that mattered.'

Using geometric mosaic tiles, Deverne turned ventilation shafts in La Défense, Paris, into objects of beauty

An intricate herringbone relief in sandstone, created by Deverne in the early 1970s as a model for a mosaic for the Cité Hospitalière in Lille

Deverne's artwork is replete with simple geometric shapes, often circles and helixes, that repeat and play off each other to create illusions of light and space

'Movement, futurism and optimism were all part of his oeuvre; mystery, purity and luxury of material were also fundamental to his repertoire,' says American dealer Robert Murphy of RCM Galerie in Paris, which began representing the artist a few years ago

A relief and mosaic by Michel Deverne

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculptures

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculpturesThe Japanese designer creates an intuitive series of bold play sculptures, designed to spark children’s desire to play without thinking

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025At Milan Design Week 2025 Japanese craftsmanship was a front runner with an array of projects in the spotlight. Here are some of our highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher