Skin in the game: Alexandra Bircken on fashion, club culture and the fragility of flesh

We profile German artist and former fashion designer Alexandra Bircken, whose complex work explores the human body as a ‘moving sculpture’ – woven with unruly desires, pleasures and violence

Alexandra Bircken often compares her work to skin. For her, it’s a membrane between internal and external; it’s what protects us, what makes us permeable and what functions as the canvas we dress and exhibit to the world. It seems logical, then, that the German artist began a career working with the second skin of humanity: fashion.

In the early 1990s, Bircken left Remscheid, her hometown near Cologne, for the UK, with her lifelong friends Wolfgang Tillmans and Lutz Huelle (she and Huelle will stage a joint show at Paris’ Fondation Pernod Ricard in November).

At Central Saint Martins, which counts Alexander McQueen, Stella McCartney and John Galliano as alumni, she studied fashion design. ‘I had been reading i-D and The Face, and [London] is where I wanted to be. The underground fashion and eccentricity didn’t exist – and still doesn’t exist – in Germany, so there was no choice,’ she explains via Zoom from her Berlin home. ‘I followed what I wanted to do, which was to play around with individuality.’

Alexandra Bircken with The Tourist, the central figure of her ‘Fair Game’ show at Kindl, Berlin. Sporting a motorcycle exhaust for a head, and carrying a sabre, she is clad in colourful attire, with epoxy resin clogs giving an illusion of levitation.

And nowhere was individuality as extreme and extravagant as it was in London in the 1980s and 1990s. In its hedonistic, polysexual and ephemeral underworld, fashion school craft collided with high-concept art; each night was an opportunity for an act of personal theatre. These were decades drenched in the brazen sexuality of Madonna, the fetish gear of Vivienne Westwood and the transgressive energy of Leigh Bowery – performer, artist, ringmaster for London’s underground club scene. The last made a huge impact on Bircken. ‘Every week you would sew something new for the weekend, for the club. It wasn’t meant to last; wearability wasn’t a big thing. This is what Saint Martins taught us: if you can’t find what you want, you make it yourself,’ says the artist, who would later lecture on the college’s MA Fashion Design course, and is now a professor of sculpture at Munich’s Academy of Fine Arts.

After graduating in 1995, Bircken co-founded the label 'Faridi', but a career in the fashion world didn’t quite scratch the itch. ‘When you work in the [fashion] market you have to meet the market. You have to make people look “beautiful”, which is why I didn’t like fashion and the system. Nobody wears anything ugly or extreme, everybody wants to look thin and sexy, the typical female stereotype, and I got really fed up.’

The solution was a gradual shift to art, one that retained sartorial sensibilities and skills, but saw the body as a ‘moving sculpture’. It involved a deep exploration of materialism, man versus machine, and man as machine.

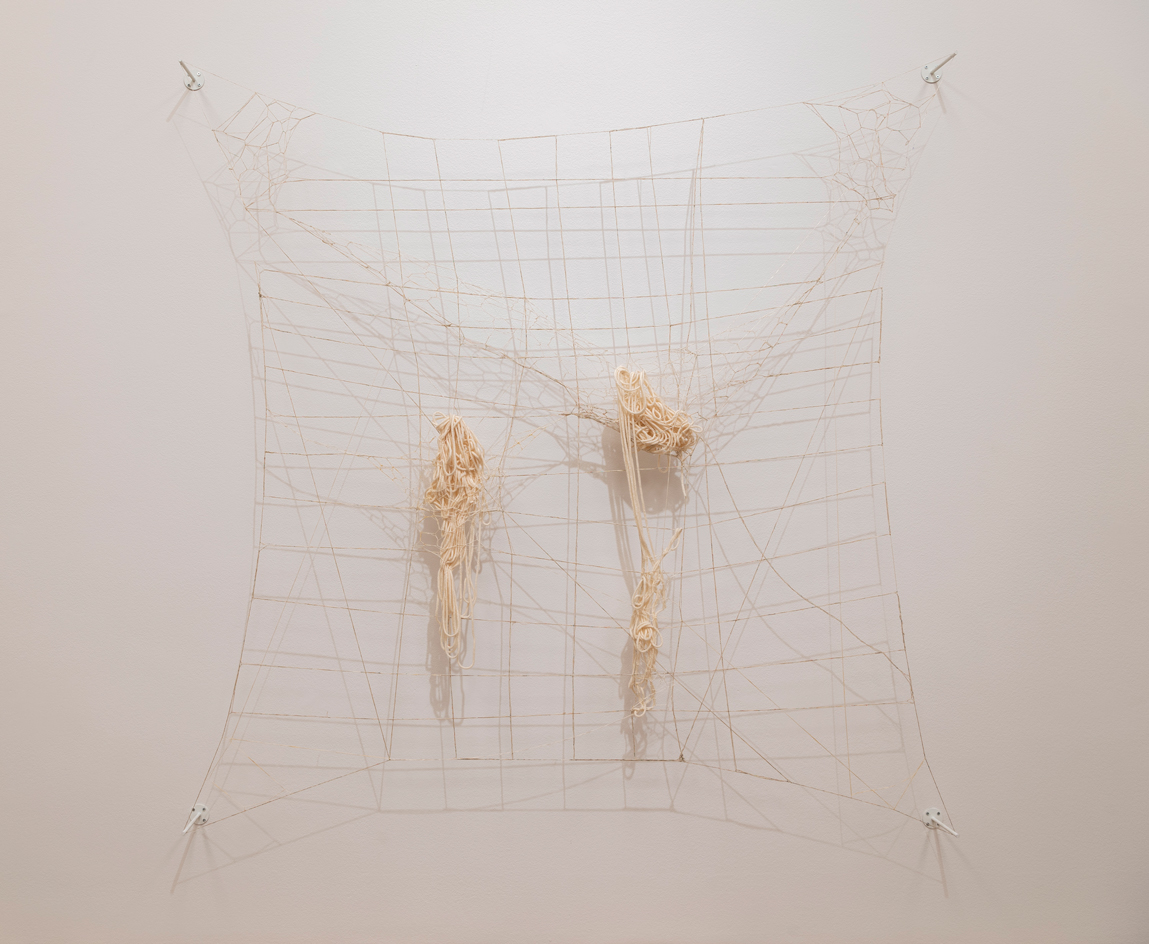

Installation view of ’Alexandra Bircken: A–Z’, 28 July 2021 – 16 January 2022 at Museum Brandhorst © Alexandra Bircken. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Bircken’s show, ‘A-Z’, which opened in 2021 at Munich’s Museum Brandhorst, and will move to southern France’s CRAC (Centre Régional d’Art Contemporain Occitanie) in March 2022, is her largest to date. The thematic show begins in 2003 with explorations into literal and symbolic ‘knotting’: from experimental early textile works and sculptures in leather, to her own placenta, preserved in Kaiserling solution. ‘A-Z’ culminates in a subtle, but significant site-specific intervention, one that reconfigures the skeleton of the Brandhorst building: wooden grilles on heating vents have been replaced by bones (cow ribs and chicken legs). ‘I had this feeling that wherever you go in the world, you walk on other people’s bones. It’s the overlaying of history,’ she says.

Another significant and frequent subject in Bircken’s work is the motorcycle and its related gear as an ultra-protective skin. She still rides, but not as much as she did. Her fascination lies in how these machines – unlike cars and bicycles – complement the shape of the body in an intimate, almost carnal union. ‘The whole body is involved. It’s very dangerous; you have to become one with it in order to survive', she says. ‘But a lot of people don’t see the gracefulness of motorcycles’.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Installation view of ’Alexandra Bircken: A–Z’, 28 July 2021 – 16 January 2022 at Museum Brandhorst © Alexandra Bircken. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

In her work, burly motorbikes are rendered defunct. They are severed to reveal their bowel-like innards, turned upside-down, or infantilised as a rocking horse; their conventionally masculine heft exposed as a myth. The motorcycle is one of many examples of Bircken’s deft manipulation of readymade objects, whether machine-made, manmade, or animal-made – all underpinned by a deep affinity for the human condition, in all its unruly variety.

Bircken’s work doesn't directly comment on the state of the world. It is not necessarily of this world. But it does highlight the fragility of flesh against the threats of an increasingly unstable, mechanised culture, asking: can bodies still hold themselves?

Bircken describes her other current show, ‘Fair Game’ in Berlin, as a comment on the pandemic’s effect on club culture, and a ‘free interpretation’ of Samuel Beckett’s The Lost Ones (1971). In the Irish writer’s short story, 200 naked bodies – one per square metre – are contained in a cylinder called the ‘abode’. The lighting and temperature fluctuate drastically, resulting in blindness, skin problems and a climate hostile to sex. The floor and walls are made of rubber, deadening all sound. There are ladders and niches in the walls – some ‘lost ones’ climb ladders to nowhere, others, vanquished, remain on the floor. Beckett’s tale is a version of hell; Bircken’s nightmare doesn't look far off – but in ‘Fair Game’, there’s more at play.

'Fair Game' at Kindl, Berlin features gimp suit-like bodies, made from black latex-painted calico and embroidered with body parts

The work is installed in the Kesselhaus (boiler room) of Kindl, previously a brewery, later a nightclub, and now a stage for contemporary arts. The space is cubic and vast: a cathedral of exposed brickwork with a glass roof. Were it not for Bircken’s bodies strewn across the floor, this might be a space of sanctity. But there is nothing sacred here. Rubber figures dangle from rafters, some hang by their necks, others scale the walls. They climb ladders made of cow ribs, stoop on niches, or lie lifeless on the floor. They are limp, faceless, deflated and void. But devoid of what? Bones, blood, stuffing, air?

Bircken first introduced these gimp-suited bodies, made from black latex-dipped calico, in ‘Eskalation’ at The Hepworth Wakefield in 2014 (where she contended with David Chipperfield’s famously irregular angles) and again in the curated group show ‘May You Live In Interesting Times’ at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019.

Her scene is the aftermath of something violent. Perhaps it began in fetishistic pleasure and took a sour turn, or was a social experiment that turned into a massacre. But it could just as well be a factory, a production line of clothes: unworn, inanimate and cold.

There are notable modifications for Bircken’s Kindl show. She has embroidered body parts onto the suits: spines, hearts, eyes, ovaries, long blond pubic hair, genitals. ‘It’s a link back to the reality of the human body, and what’s under the skin,’ she says. There are real ostrich eggs placed where wombs might have been; they rupture with oily rags similar to those used to clean motorcycles; possibly a symbol of birth, or, as Bircken notes, a reference to a molotov cocktail.

This time, the suits come with genitals. During our call, she picks up a pen and paper, draws a phallus and holds it up to the camera. ‘You pull it out and you have a penis, or you stick it in and you have a vagina’. This toying with genitalial forms felt like a logical development for Bircken, but she is keen to keep things non-descriptive: ‘There are no testicles, no labia, it’s very simple,’ she explains.

Although Bircken has used gimp-suited figures in her previous works, here she has embroidered on body parts, as well as placing bread and ostrich eggs where wombs might have been

There is one exception in this sea of tar-coloured flesh: The Tourist, a figure who presides over the battleground. She is clad in American football-esque shoulder pads, bold, block-coloured attire with a motorcycle exhaust for a head and epoxy resin clogs on her feet, giving an illusion of levitation. But is she a perpetrator or saviour? Has she slaughtered them all, or arrived too late to help?

Elsewhere, coloured glass incubators resembling alien eggs contain a variety of stuffed objects. In the centre of the space, another black rubber body is draped over beer barrels, which are interspersed with loudspeakers. They emit a soundtrack composed by Bircken’s partner, the musician Thomas Brinkmann. ‘It’s clubby, but then it’s also breathing or a heartbeat. It’s a relentless boom boom boom,’ she says. This sound – pulsating around objects which may have once had a pulse – references the building’s history, and cuts through the deathly silence of this pitiful scene.

Is this a fair game, as the artwork title suggests? Is it a game at all? Is it game as prey, or, in a culture of ever-intensifying anger and accusation, people as fair game for criticism? However you read it, Bircken has created an ambiguous, impenetrable scene. All we have is speculation.

Bircken’s work has the intricacies of a vascular system – a tapestry woven with all that makes us complexly and beautifully human: our tangled, changeable and unattainable desires. We are deeply corporeal, but ultimately machines. In celebrating craft, and obliterating material hierarchies she weaves disciplines together like threads on a loom. In an overwhelming world, Bircken gets under the skin.

Bircken pictured with her installation 'Fair Game' at Kindl Berlin, which includes coloured glass incubators resembling alien eggs containing a variety of stuffed objects

Installation view of ’Alexandra Bircken: A–Z’, 28 July 2021-16 January 2022 at Museum Brandhorst © Alexandra Bircken. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Installation view of ’Alexandra Bircken: A–Z’, which features a 2017 untitled sculpture of the artist’s own placenta preserved in Kaiserling solution (pictured left) © Alexandra Bircken. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Installation view of ’Alexandra Bircken: A–Z’, 28 July 2021-16 January 2022 at Museum Brandhorst © Alexandra Bircken. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Installation view of ’Alexandra Bircken: A–Z’, 28 July 2021-16 January 2022 at Museum Brandhorst © Alexandra Bircken. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Installation view of ’Alexandra Bircken: A–Z’. In a site-specific intervention, Bircken replaced wooden grilles on heating vents with bones (cow ribs and chicken legs).© Alexandra Bircken. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

INFORMATION

Alexandra Bircken, ‘Fair Game’ is on until 15 May 2022 at Kindl, Berlin. kindl-berlin.com

A version of this article is featured in the March 2022 issue of Wallpaper*, on newsstands now and available to subscribers

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewellery

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewelleryNikos Koulis experiments with unusual diamond cuts and modern materials in a new collection, ‘Wish’

By Hannah Silver

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

MK&G’s ‘Glitter’ exhibition: a brilliant world-first tribute to sparkle and spectacle

MK&G’s ‘Glitter’ exhibition: a brilliant world-first tribute to sparkle and spectacleMK&G’s latest exhibition is a vibrant flurry of sparkles and glitter with a rippling Y2K undercurrent, proving that 'Glitter is so much more than you think it is'

By Hiba Alobaydi

-

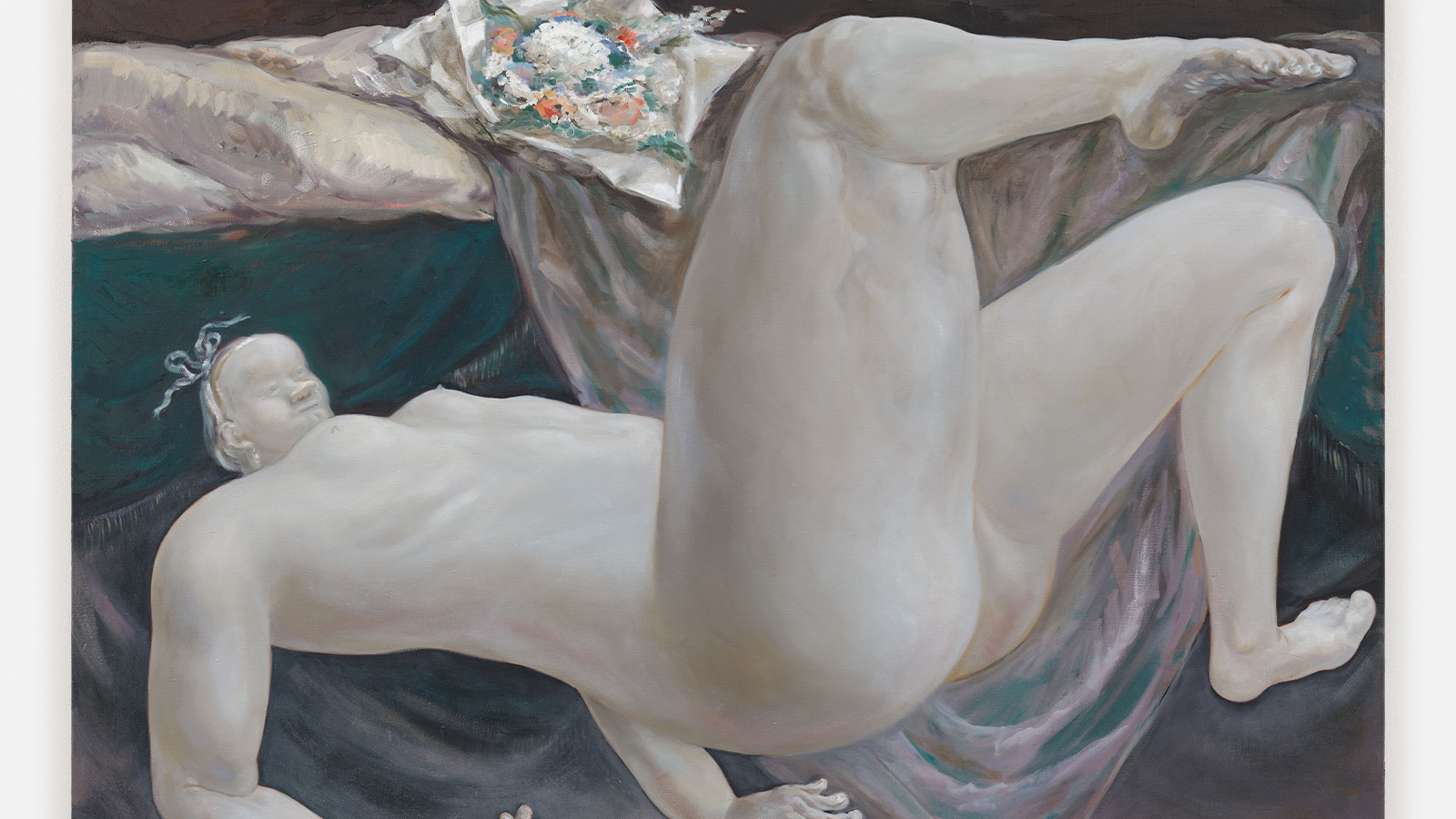

Louise Bonnet’s falling figures depict an emotional narrative to be felt rather than told

Louise Bonnet’s falling figures depict an emotional narrative to be felt rather than toldLouise Bonnet’s solo exhibition 'Reversal of Fortune' at Galerie Max Hetzler in Berlin, nods to historical art references and the fragility of the human condition

By Tianna Williams

-

Inside E-WERK Luckenwalde’s ‘Tell Them I Said No’, an art festival at Berlin's former power station

Inside E-WERK Luckenwalde’s ‘Tell Them I Said No’, an art festival at Berlin's former power stationE-WERK Luckenwalde’s two-day art festival was an eclectic mix of performance, workshops, and discussion. Will Jennings reports

By Will Jennings

-

Alexandra Pirici’s action performance in Berlin is playfully abstract with a desire to address urgent political questions

Alexandra Pirici’s action performance in Berlin is playfully abstract with a desire to address urgent political questionsArtist and choreographer Alexandra Pirici transforms the historic hall of Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof into a live action performance and site-specific installation

By Alison Hugill

-

Berlinde De Bruyckere’s angels without faces touch down in Venice church

Berlinde De Bruyckere’s angels without faces touch down in Venice churchBelgian artist Berlinde De Bruyckere’s recent archangel sculptures occupy the 16th-century white marble Abbazia di San Giorgio Maggiore for the Venice Biennale 2024

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

Lawrence Lek’s depressed self-driving cars offer a glimpse of an AI future in Berlin

Lawrence Lek’s depressed self-driving cars offer a glimpse of an AI future in BerlinLawrence Lek’s installation ‘NOX’, created with LAS Art Foundation, takes over Berlin’s abandoned Kranzler Eck shopping centre

By Emily Steer

-

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installation

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installationIn Antarctica, Kyiv-based architecture studio Balbek Bureau has unveiled ‘Home. Memories’, a poignant art installation at the remote, penguin-inhabited Vernadsky Research Base

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

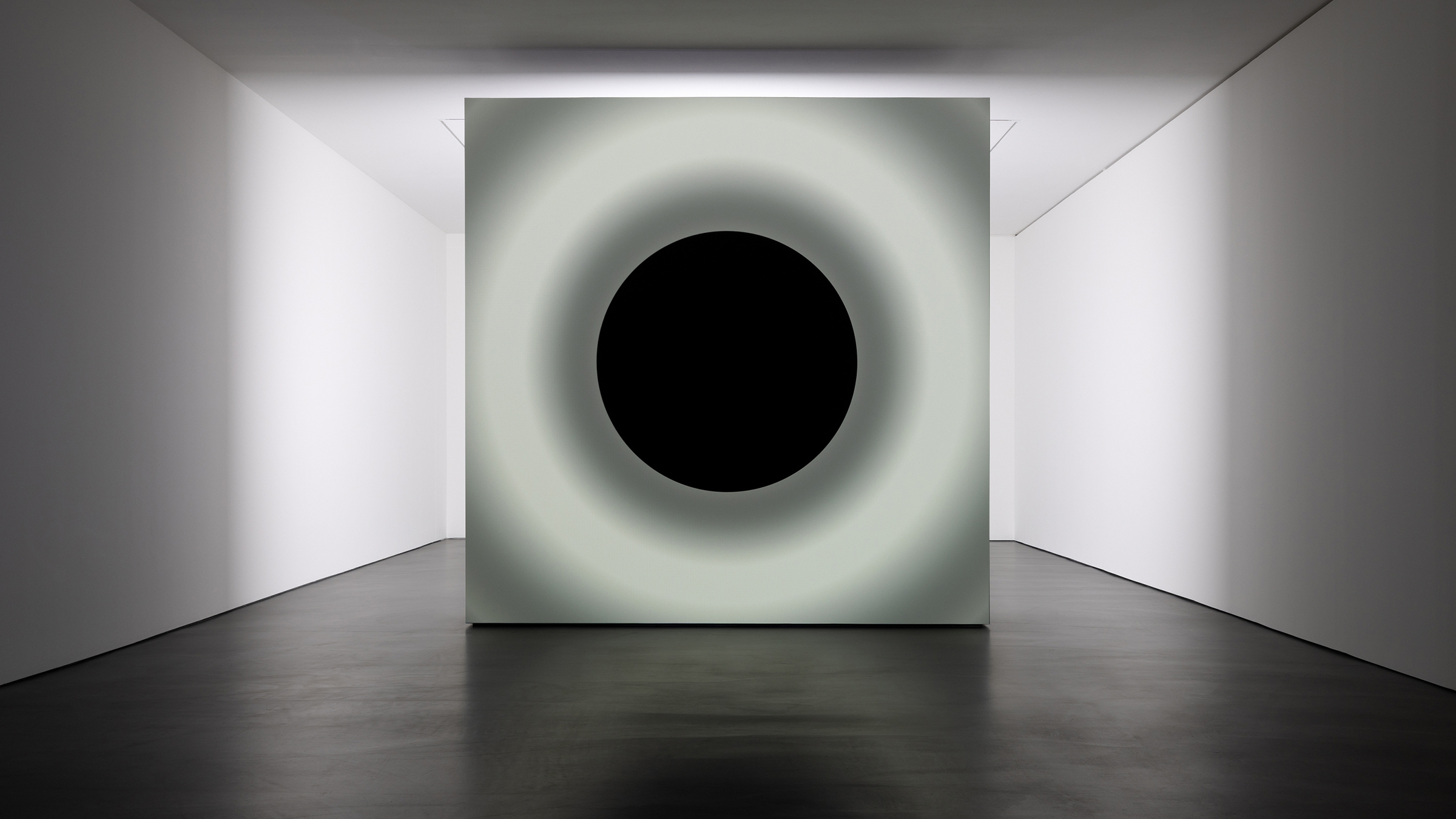

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensation

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensationAt Esther Schipper gallery Berlin, artists Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen draw on the elemental forces of sound and light in a meditative and disorienting joint exhibition

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith